Song of a Deathless Life

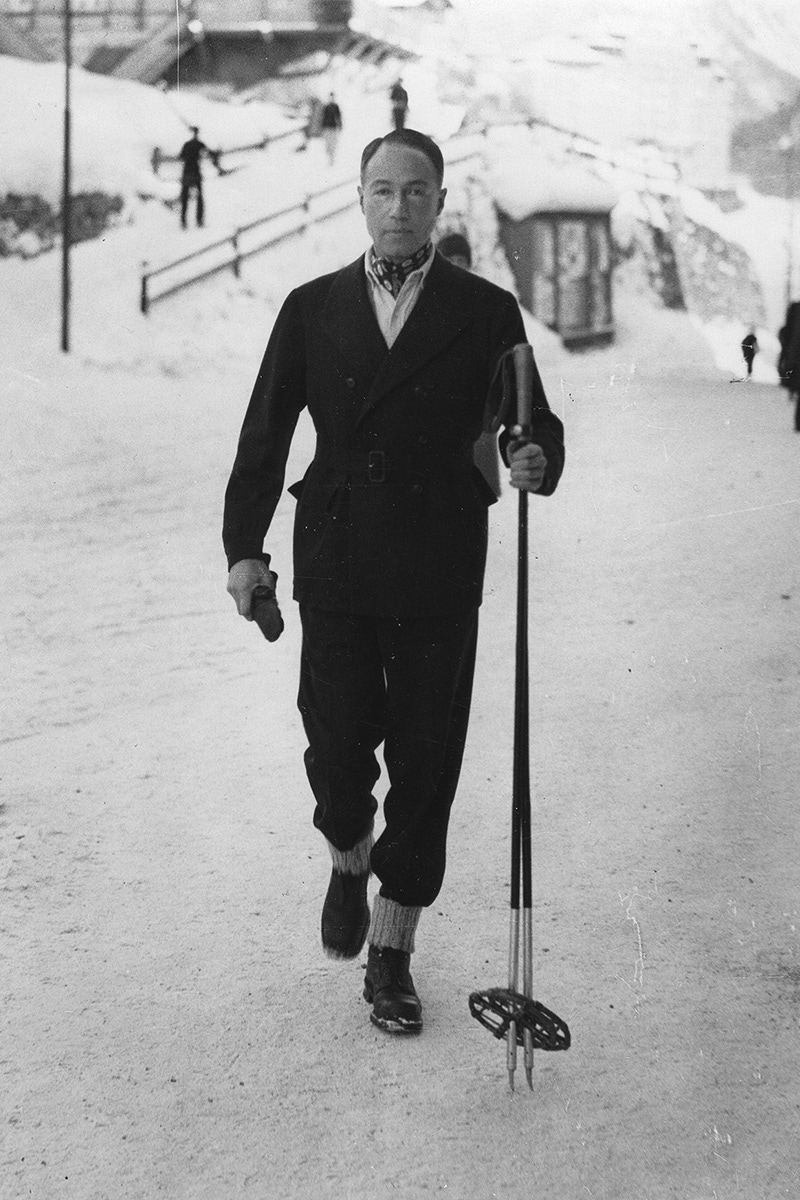

Sir Philip Sassoon indicted himself as ‘a thing of naught, a worthless loon’. But this interwar politician, fixer, aesthete and man of mystery was anything but.

In 1923, the writer and editor C.K. Scott Moncrieff produced a barbed ode called A Servile Statesman, which read, in part: 'Sir Philip Sassoon is a member for Hythe He is opulent, generous, swarthy and lithe The houses he inhabits are costly but chaste But Sir Philip Sassoon is unerring in taste'.

The Sassoon's were known as “the Rothschilds of the East” — they claimed to be descended from King David, with their ancestors transported to Babylon by Nebuchadnezzar on the sacking of Jerusalem in 600BC. They became leaders of the exiled Jewish community, wheeler-dealing in the souks of Baghdad; Sassoon’s paternal great-grandfather, David, established a major trading empire from boomtown Bombay in the 1830s, trafficking in everything from silver and gold to wool and wheat via opium and cotton. Inevitably, there was an eventual Rothschild merger, with Philip’s father, Edward (sporty, outdoorsy), marrying Aline de Rothschild (arty, book-loving), culminating in Philip’s arrival in 1888 at Hôtel de Marigny, the vast Parisian particulier commissioned by his grandfather Baron Gustave de Rothschild.

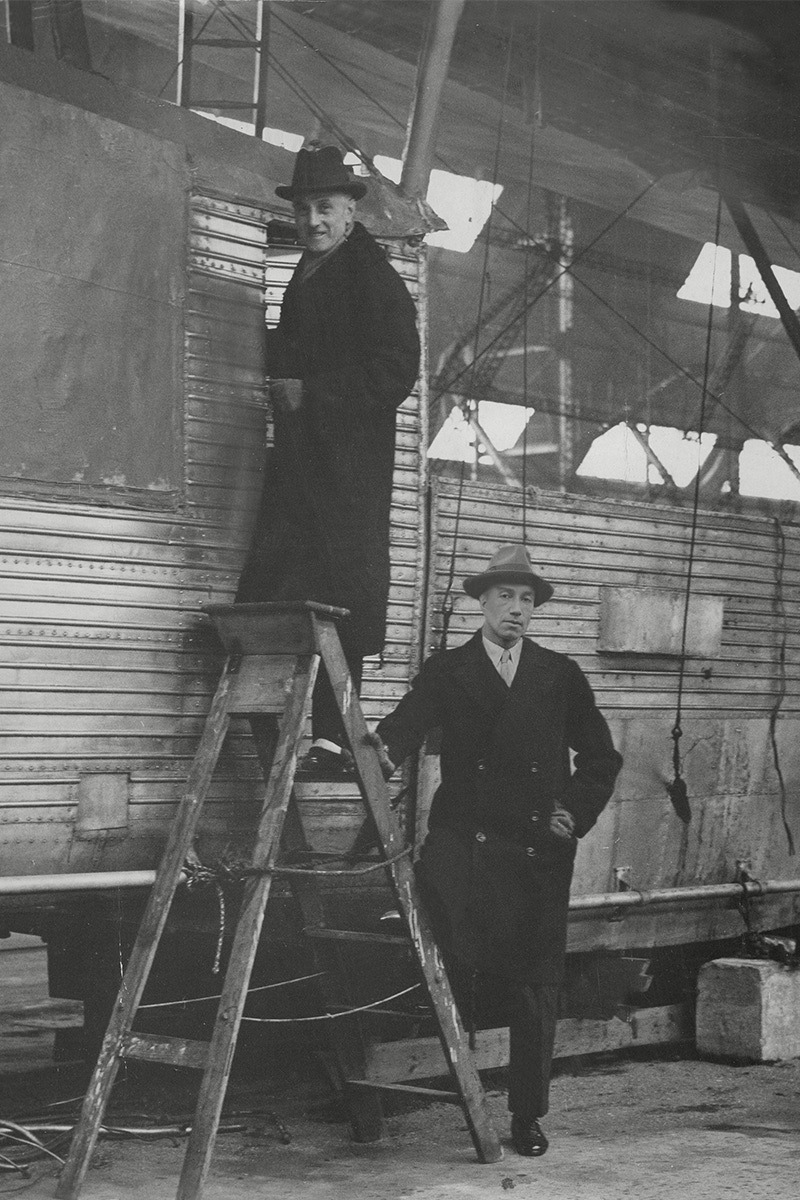

Sassoon’s reputation for unstinting hospitality was already such that, when Sir Douglas Haig, the commander of British forces in France during world war I, recruited him as his private secretary, he quipped that he’d attached a first-class dining car to his train. During the conflict, Sassoon, according to one contemporary, “flitted like some exotic bird of paradise against the sober background of GHQ”.(He also took pains to avoid his first cousin, the war poet Siegfried Sassoon, whose verse pilloried the failings of the officer class versus the sacrifice of the frontline Tommies; they maintained a cautious distance throughout their lives.)

Subscribers, please allow up to 3 weeks to receive your magazine