The Advent of the Loafer

The history of the loafer and its many comfortable, timesaving permutations.

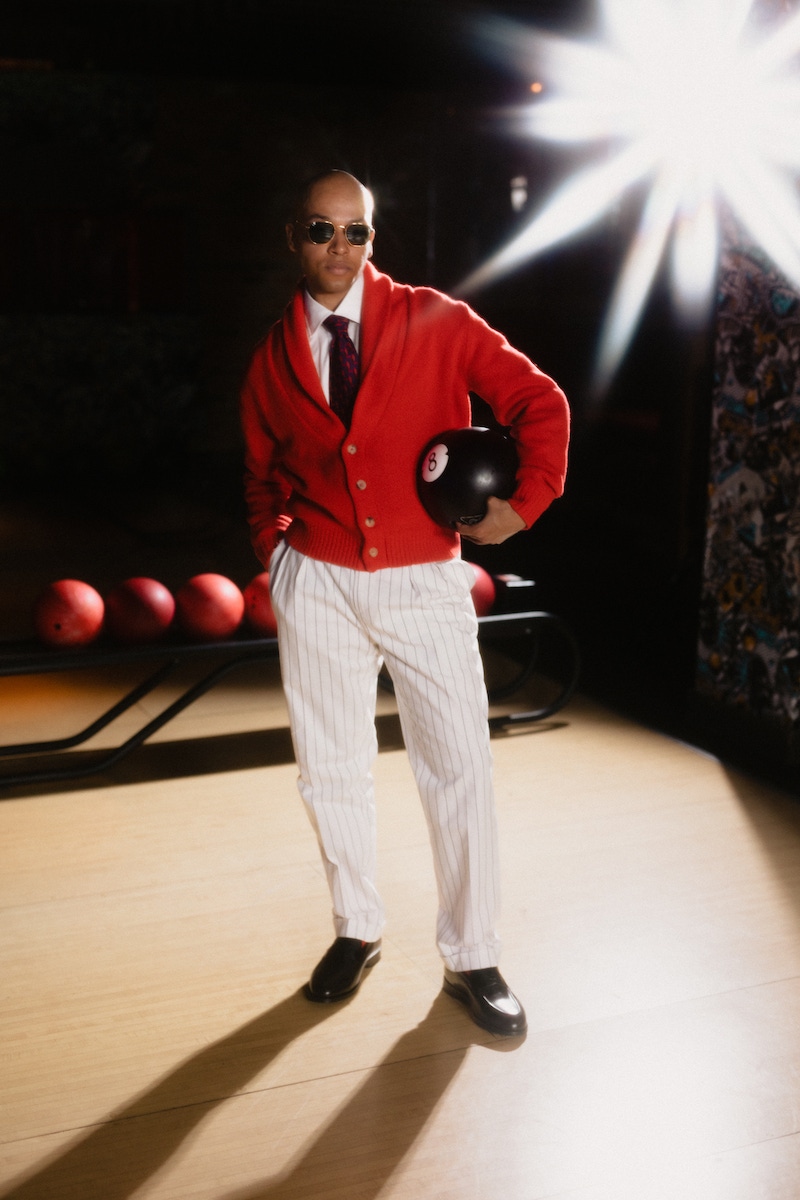

The original men’s style minimalist, Beau Brummell may have freed us from frills, frippery and lace, however it was the advent of the loafer that liberated men from the tyranny of laces. Unlike Brummell — a monied man of leisure who took hours primping his ’fit each day — the modern gentleman has scant seconds to spare in his everyday sartorial preparations, and the loafer saves us valuable minutes to spend on more fruitful pursuits (bonding with our offspring, performing callisthenics, or checking lingerie models’ Instagram Stories, perhaps). For this, we must be thankful. But to whom should we offer our gratitude, you ask? Read on, sir.

London shoemaker Wildsmith is credited with creating the first modern loafer in 1926 for client King George VI, in response to the stuttering regent’s request for a bespoke casual shoe he could ‘loaf’ around his country houses in. A beefier ready-to-wear rendition suitable for outdoor use was soon put into production, and the style was quickly emulated by many more of Britain’s gentlemen’s shoemakers.

Across the sea in Norway, meanwhile, Nils Gregoriusson Tveranger, who’d studied shoemaking in the United States, developed a style jointly inspired by Native American footwear and a moccasin-like shoe traditionally worn by the hunters, fisherman and farmers of his fjord-side home in Aurland. The ‘Aurland Moccasin’ found favour throughout Europe in the 1930s, and visiting Americans brought the shoes home as souvenirs. Knowing a good thing when they saw it, Maine-based shoemaker GH Bass launched its version of Tveranger’s shoe, named the Weejun in homage to its Norwegian origins, in 1934.

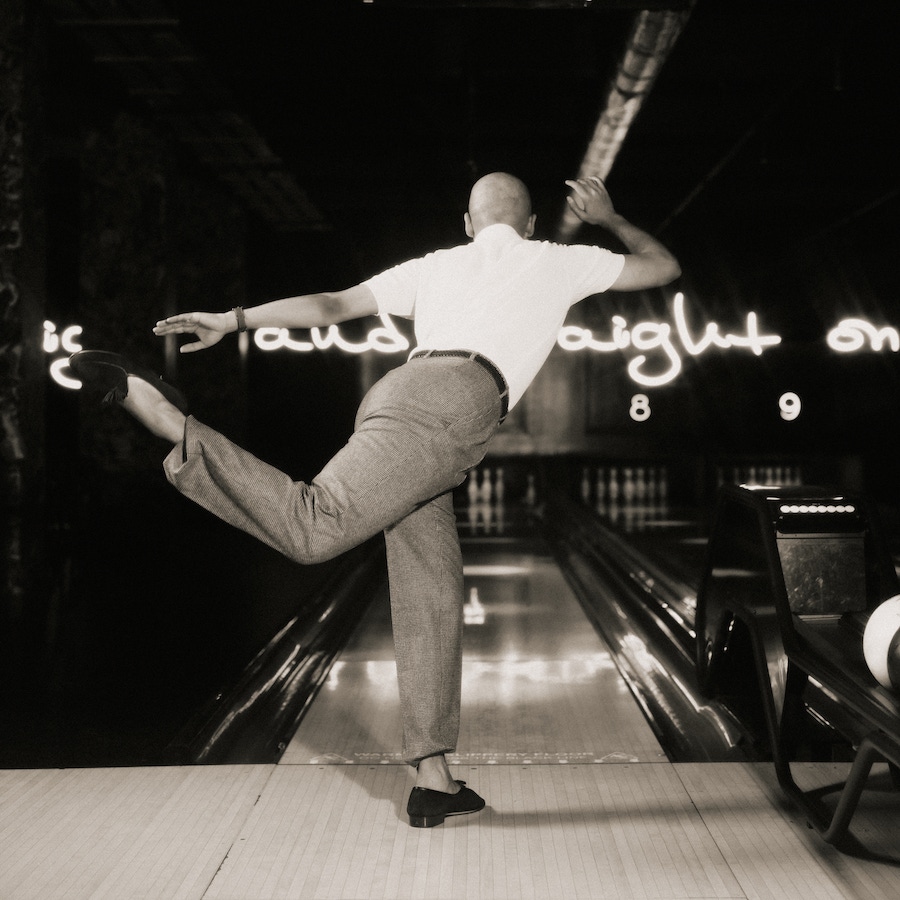

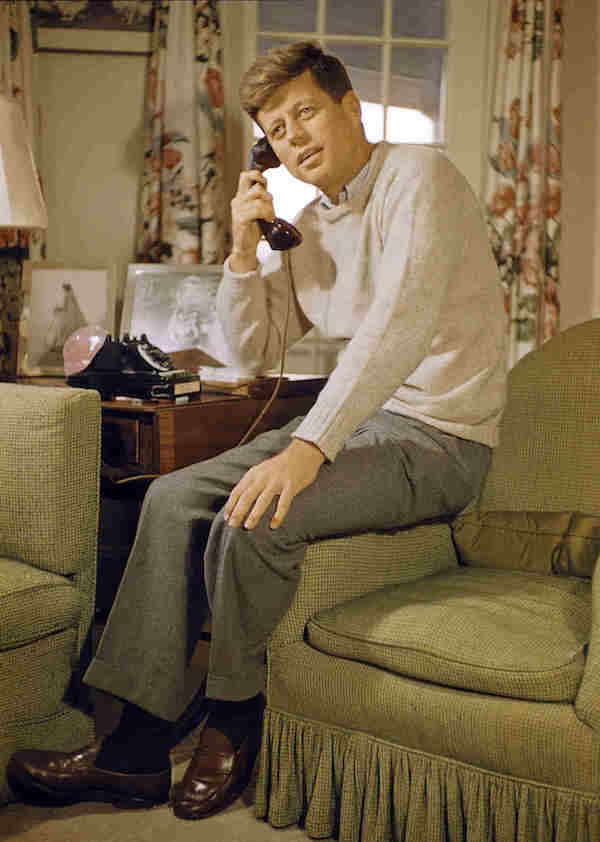

Championed by US men’s style bibles Esquire and Apparel Arts, the loafer became popular with dapper young chaps on American college and prep school campuses, who took to inserting two pennies into the cut-outs on the shoes’ saddle, either as a form of embellishment or to provide ready currency for an emergency phonebooth call. It was the college kids who first sported the loafers-sans-socks look that’s a common fashion trick today, but was initially a matter of hurried dishevelment. “Guys who lived in the dorms wore them that way,” according to menswear sage G. Bruce Boyer. “If they were late for their first class they would put on their loafers without putting on their socks first. Other guys would show up in their pyjamas.”

Former Ivy Stylemeisters in the States carried on wearing loafers when they graduated and entered the corporate world, and the natty tasseled iteration popularised by Alden in the 1950s (and later perfected in the form of Anthony Cleverley’s De Rede) was enthusiastically adopted by urbane sophisticates on the east and west coasts. But back in Britain and on the Continent, the loafer remained strictly a casual choice.

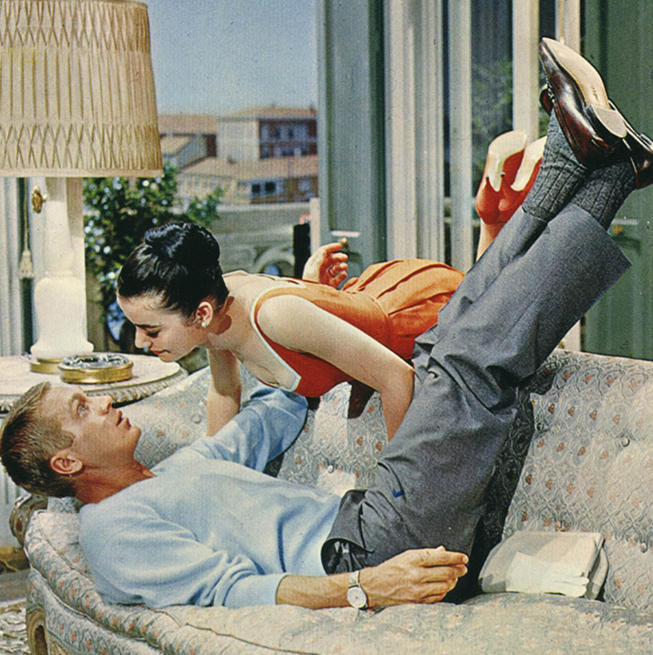

The introduction, by an exclusive Florentine leathergoods house named Gucci, of a loafer featuring 'snaffle' horse bit hardware across the saddle, proved a gamechanger. Aldo Gucci, the son of the firm’s founder, who’d been tasked with spearheading the family business’s expansion into the United States, had noticed the loafer’s popularity in the US and was struck by the idea that a slick, sleek-lined, luxurious version, suited to being worn with both tailoring and casualwear, would pique Americans’ interest. He wasn’t wrong. From the moment Gucci’s New York store doors opened in 1953, the Gucci horsebit loafer flew off the shelves.

Initially championed by chic celebrities and the jet set, by the 1970s, Gucci loafers were considered so formal-appropriate that patrician CIA chief George HW Bush wore them for meetings with President Ford at the White House. In the ‘80s, they became ubiquitous among pinstriped power-suited Wall Street masters of the universe and City of London yuppies. Thanks to Gucci (whose transformation from obscure Italian atelier to ubiquitous global luxury brand was utterly driven by the horsebit), the loafer’s acceptance in dressed-up metropolitan settings was complete.

Possessing “the comfort of the moccasin while adding the fashion and elegance of a dressy shoe,” wrote G. Bruce Boyer, the Gucci loafer “was the first shoe that bridged the gap between casual and business wear.” At home “in corporate board rooms and country clubs alike,” according to Boyer, “there is no question that this now legendary shoe deserves its reputation for having revolutionised casual footwear, which is the reason a Gucci slip-on is included in the costume collection of New York’s Metropolitan Museum.”

Like Aldo Gucci before him, in the late 1970s, a young third-generation shoemaker from Le Marche, Italy, named Diego Della Valle was inspired by America’s laid-back style to create a luxurious driving moccasin. “In Italy people still tried to be elegant at the weekend: a suit, tie and white shirt, especially on Sunday. In America it was completely different. The weekend was like a religion there, and people tried to be very, very relaxed,” Della Valle explained in a 2011 interview. “Sometimes it was not very good taste! But my idea was, why not make more relaxed shoes that are also elegant and chic?”