The Axe Factor

For nearly a century the guitar has enabled modern music to exist in a permanent state of change. And from Stevie Ray Vaughan and Duane Allman to Hendrix and Marr, there has been no shortage of revolutionaries.

Before the guitar hero, before even the concept of ‘lead guitar’, there was Robert Johnson. To say his playing is underestimated would be a stretch — this is, after all, the man who was said to have sold his soul to the devil at the crossroads in exchange for his talent. But what Johnson played was truly remarkable, even without considering that he did it first. For historians, he was the pioneer of the boogie shuffle, the blues pattern that led directly to rock ’n’ roll, but that doesn’t really matter. Listen to a collection of his very few recordings from the 1930s and you hear an incredible range of tone, played with perfect accomplishment and feeling: the exuberant vamping of Sweet Home Chicago, the shivering bottleneck plucking of Crossroad Blues, the tender melodiousness of Come On in My Kitchen. Perhaps the defining comment on his virtuosity is from Keith Richards, who asked on first hearing Johnson, “Who’s the other guy playing with him?”

After Johnson, the electrified blues separated the role of vocalist and guitarist, focusing attention on the instrument and its player. The guitar hero began here, in the shape of Howlin’ Wolf’s Hubert Sumlin, whose clipped, urgent sound reinforced the power of his singer’s growl, in the lyrical peals of B.B. King, the exuberant attack of Muddy Waters, or the sheer drama of Albert King, whose every perfectly placed note is a cry of desperation. While all of these players influenced rock, there was something about the last that translated to the guitar hero through the years, from Hendrix and Clapton in the sixties to a new generation in the eighties, and none of them more than Stevie Ray Vaughan.

This Texan native had played throughout the seventies, when blues was at the front of no one’s mind, but in the next decade he almost single-handedly revived the form. Undeniably flashy, he was, however, a dedicated student, able to play anything and anyone, and bold enough to cover even Jimi Hendrix’s Voodoo Chile. His cranked-up, hyperactive playing blew the dust off the blues and returned it to the living, breathing expression it had been before, all of life in full colour. He had the chops for the fans of hard-rock stunt guitarists like Eddie Van Halen, he had the traditional roots to please the blues purists, and he had the good fortune to come to the attention of David Bowie. Chosen as his lead guitarist for the Let's Dance album, Vaughan swathed a slick pop album in electrified blues and kickstarted his solo career.

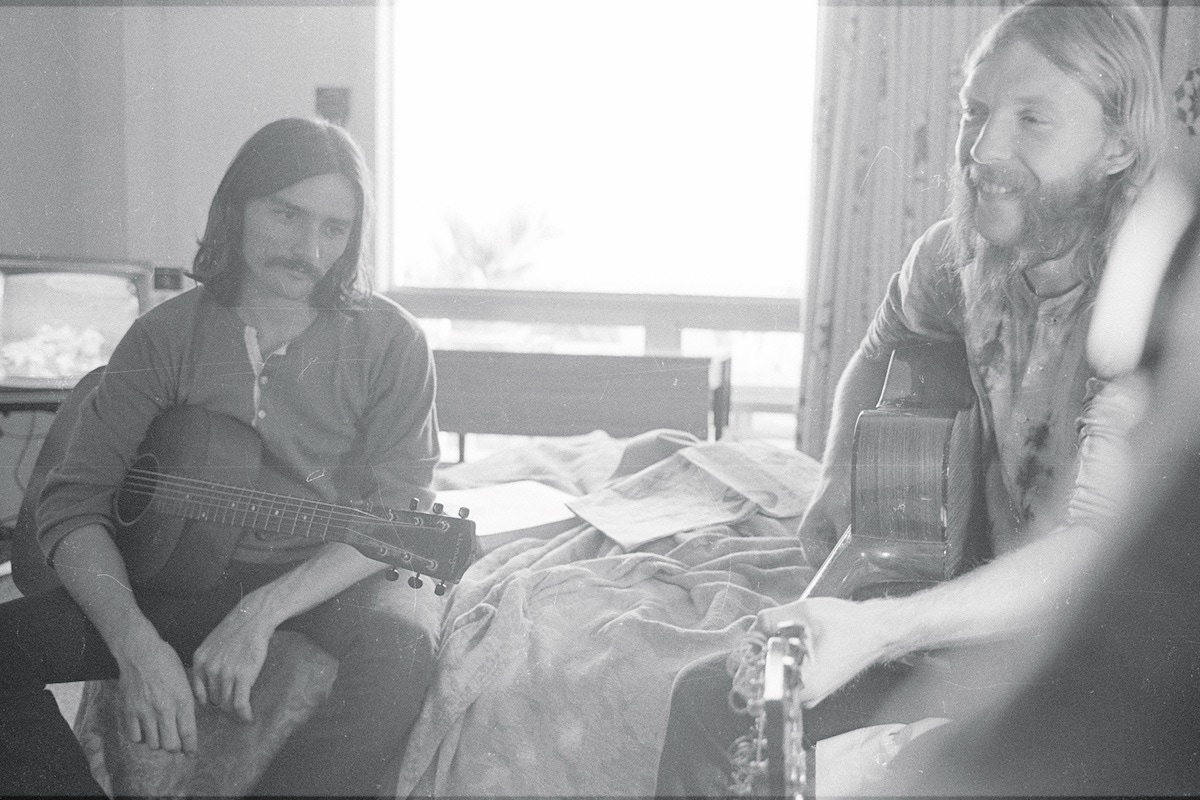

Much of Vaughan’s reputation is in the might-have-been, however, as he died aged 35 in a helicopter crash in 1990. Another great white hope who left a small but perfectly played legacy was Duane Allman, taken at just 24 in a motorbike crash in 1971. Born in country capital Nashville but based in soul-land Georgia, his band, the Allman Brothers, took in not only the blues but also country and jazz, helping to create the southern rock sound that dominated music in the early 1970s. Allman’s greatness is perhaps more remarkable since his most famous work was in tandem with other ludicrously talented guitarists: in his own band with Dickey Betts, whom Allman called “the good one”, and with Eric Clapton in his Derek and the Dominos side project. The Dominos produced Allman’s most famous lick, the opening to Layla, where his slide- guitar figure raises an already great song to another level, but his other work was equally inspired. There’s the frenzied pair of solos on the band’s live recording of Whipping Post that have gone into legend, but just as impressive is his pre-band outing as a session player on Wilson Pickett’s Hey Jude, where in the final minute he breaks through the massed horns and the singer’s hollering and lets loose, truly taking a sad song and making it better.

Read the full feature in Issue 81 of The Rake - on newsstands now.

Available to buy immediately now on TheRake.com as single issue or 12 month subscription.

Subscribers, please allow up to 3 weeks to receive your magazine.