THE PINT-SIZED BARBARIAN

He ‘fought big’ and ‘dreamed big’, according to David Lynch, and was, his daughter said, the master of Italian guilt. Dino de Laurentiis was a five-foot-something giant of the movies, the legendary producer behind classics such as Serpico and the careers of Lynch and Cronenberg.

“He never feared failure, and this is the only way you can be successful in life. I learned that from Dino.” So said Arnold Schwarzenegger at the funeral of the Italian film producer Agostino ‘Dino’ de Laurentiis. Dino’s C.V. reads like a surrealist notebook, timeless masterpieces like La Strada, Serpico and Blue Velvet cheek-by-jowl with flamboyant catastrophes. An ingenious financier and talent spotter, as well as an adventurous anti-snob, he was instrumental in the careers of neorealist icon Silvana Mangano (whom he later married), Al Pacino, David Lynch and Schwarzenegger, as enlightened and audacious an operator in post-war Italy as in eighties Hollywood.

De Laurentiis was born in the Neapolitan seaside region of Torre Annunziata in 1919. After early work as a truck driver and a travelling salesman for his father’s pasta company, he applied to the Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia, initially as an actor, though not for long: “I see my face in the mirror and I said, ‘No, my ambition is not to be an actor’.” Army service during world war II delayed his film career, but on his return to Italy he took a producing job at Lux studios. Buoyed by the success of his 1949 film Riso Amaro (Bitter Rice), which starred his future wife, Mangano, he formed his own company in 1950 with Lux colleague Carlo Ponti.

Just as comfortable purveying Roberto Rossellini’s state-of-the-nation neorealism as the comedies of Naples’ favourite clown, Toto, Ponti and de Laurentiis combined these two sensibilities in Federico Fellini’s La Strada (1954), a lyrical fable about the kinship between a circus strongman (Anthony Quinn) and the small young woman who accompanies him (Giulietta Masina). Fellini had a nervous breakdown days before its release, and its screening at Venice caused public brawls between fans and critics, but it went on to win the Oscar for best foreign film and is widely considered one of the finest films ever made, a crucial pivot in European cinema’s shift from war-shadowed social realism to a more abstract aesthetic (Bob Dylan also cited its influence on Mr. Tambourine Man).

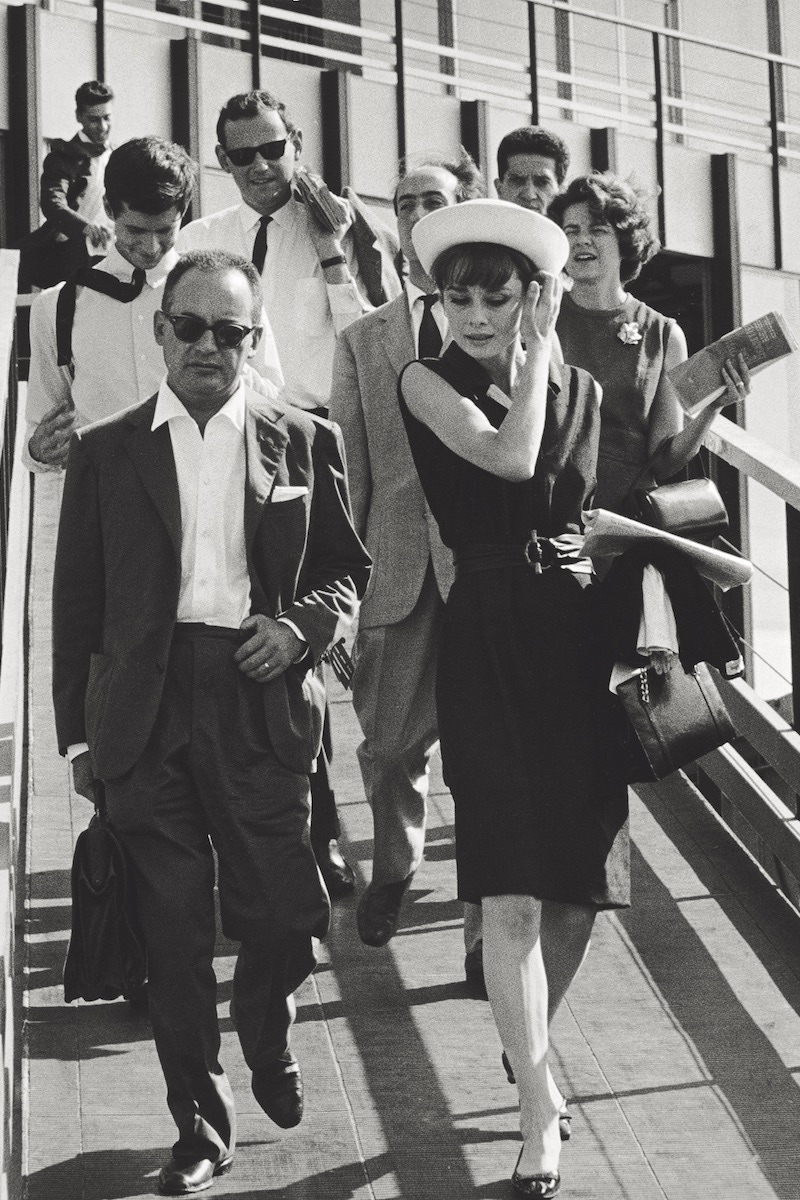

When Ponti married Sophia Loren and left for America, de Laurentiis stayed in Italy and mixed Italian neorealist iconography with an international eye for updated classics. Alongside films with Fellini, Luchino Visconti and Bicycle Thieves director Vittorio de Sica, he persuaded Kirk Douglas to appear in Mario Camerini’s Ulysses (1954), then Audrey Hepburn and Henry Fonda in King Vidor’s 1956 War and Peace (De Laurentiis would soon voyage across the Atlantic in the other direction).

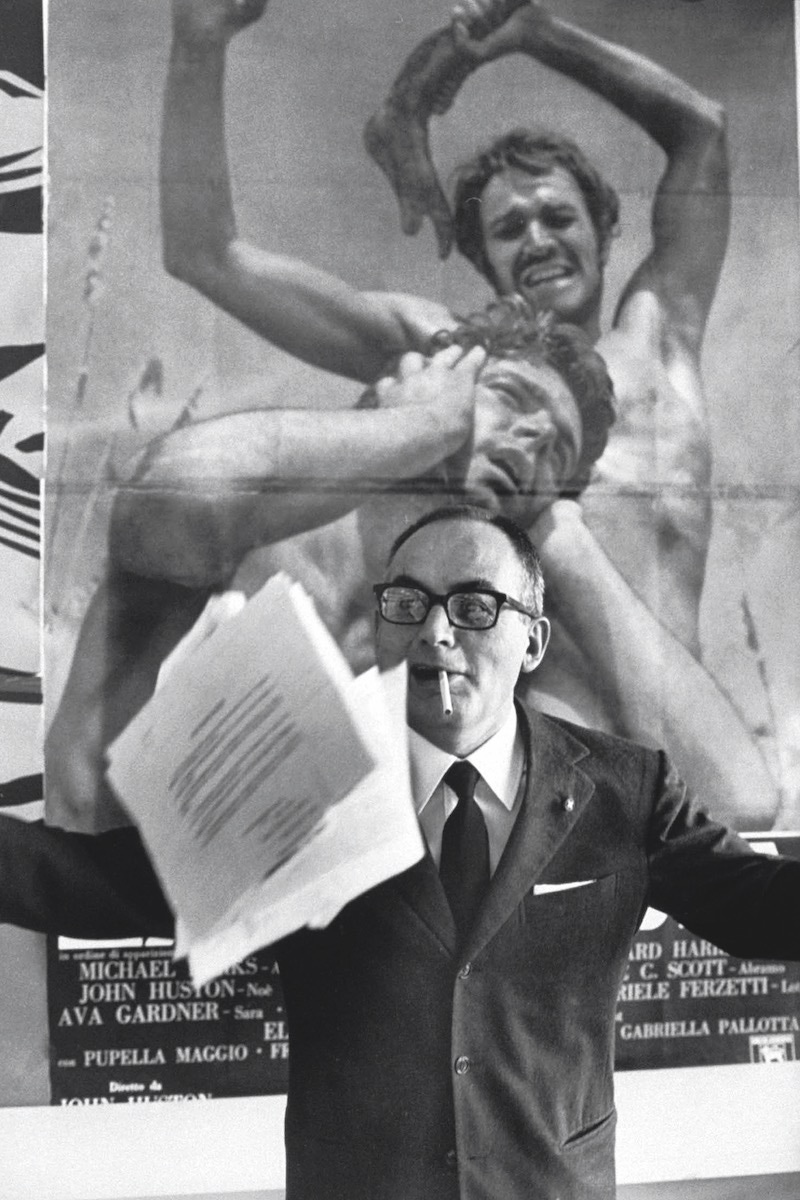

In the early sixties, de Laurentiis built his own studios in the Lazian countryside south of Rome to qualify for government funding. Dinocitta was an early pioneer of the international co-production, able to afford Hollywood stars with money saved from using local technicians. It wasn’t all smooth sailing: John Huston’s The Bible (1966) ran extravagantly over budget; Waterloo (1970), which cast Rod Steiger as Napoleon and thousands of Soviet Army soldiers as unpaid extras, was delayed by inclement weather; and he missed out on La Dolce Vita because he wanted Paul Newman for the Marcello Mastroianni role (a tantalising alternative film universe). A quintessential high-low de Laurentiis work was Roger Vadim’s Barbarella (1968), an eroticised sci-fi starring Jane Fonda and mime master Marcel Marceau. A cult tonal mishmash with eight credited screenwriters, its costumes inspired Jean-Paul Gaultier and its scientist character Durand Durand gave Simon Le Bon an idea for a band name.

Amid legal battles with Fellini over unmade projects and new government restrictions on what could legally be called an Italian movie, de Laurentiis left Italy in the mid-seventies for Hollywood, where his Catholic tastes transfused into English with an Italo energy. The themes of his cinema mirrored those of his life. After crime drama The Valachi Papers (1972) brought him threats from the mafia, Dino produced Sidney Lumet’s Serpico (1973), a pulsating film about a cop who takes on police corruption and one of Pacino’s three immortal roles alongside The Godfather and Dog Day Afternoon.

De Laurentiis tempered his slate of arthouse masters (Ingmar Bergman’s The Serpent’s Egg), Old Hollywood (John Wayne’s last film, The Shootist) and New Hollywood (Faye Dunaway’s Three Days of the Condor; William Friedkin’s The Brink’s Job; Milos Forman’s Ragtime) with postmodern shlock (Michael Winner’s Death Wish; a 1976 remake of King Kong) and a prophetic fondness for comic-book adaptations, especially Flash Gordon (1980) and John Milius’s Conan the Barbarian (1982). Schwarzenegger said that the first time he met Dino, he asked, “Why does such a tiny guy like you need such a big desk?” (Dino was 5’4”). Yet de Laurentiis punched way above his weight. As a counterpoint to Reagan’s eighties, he found two Davids at the darkest edges of America’s fantasies: David Cronenberg, with whom he made Dead Zone (1983), and David Lynch.

Though Lynch’s Dune (1984) was a fascinating box-office bomb, de Laurentiis kept faith in Lynch, founding his own De Laurentiis Entertainment Group (DEG) in the same year and financing their second collaboration, Blue Velvet (1986). It would become one of the richest, most unsettling works of mainstream American cinema, kitsch as high-art, a perfectly paced nightmare with a hellish Dennis Hopper as the infantile id of male sexual entitlement (remind you of anyone?)

The year de Laurentiis became an American citizen — 1986 — also saw the release of Michael Mann’s Manhunter, the first screen portrayal of Hannibal Lecktor (played by Scottish actor Brian Cox). Rumour has it that de Laurentiis changed the title from Thomas Harris’s book Red Dragon as he’d had a flop with Michael Cimino’s The Year of the Dragon and didn’t want to risk releasing another film with the word ‘dragon’ in it. Beyond film, his business ambitions included the DDL Foodshow (two gourmet Italian markets in New York and L.A.), a hotel on the Pacific island of Bora Bora, an upscale delicatessen, and a studio complex in North Carolina.

Alas, the winds of fortune turned again. In 1989, he was forced to resign from DEG, which then filed for bankruptcy. He passed on The Silence of the Lambs (the third film ever to win all five major Oscars); to compensate he bid $10 million for rights to Ridley Scott’s Hannibal (2001), then produced another acclaimed film in the canon called, despite his previous superstitions, Red Dragon (2003). At the end of his career he dabbled in horror sequels (Halloween II, Evil Dead II), big-name curios (like the only film directed by author Stephen King, a close friend), and embellished historical dramas like U-571 (2000), which starred Matthew McConaughey, Harvey Keitel and Jon Bon Jovi as American submariners. Tony Blair described it as an “affront” to British sailors.

At the 2001 Oscars, Sir Anthony Hopkins presented him with the Irving G. Thalberg Memorial award. Dino dedicated the award to six women in his life: his three daughters (film producers Raffaella and Francesca, and actor Veronica) and Martha Schumacher (whom he met during Dune) and their daughters Carolyna and Dina (his son Federico had died in a plane crash in 1981). The de Laurentiis name continues to transcend various industries, from food (granddaughter Giada de Laurentiis is an Emmy-winning T.V. chef) to football (nephew Aurelio de Laurentiis is chairman of Napoli football club).

De Laurentiis died aged 91 in Beverly Hills in 2010. At his funeral many of the guests wore red, his favourite colour. Lynch said that he “fought big” and “dreamed big… Ten grown athletic men combined, on PCP, would not equal even a tiny fraction of the energy that Dino had every day… Dino was like a steamroller working, dreaming and thinking the movies.” He taught Baz Luhrmann “how to have fun”; his daughter Carolyna called him a “master of Italian guilt”.

He was also a master of failure, not because he failed but because he knew how to harness it. He accepted this responsibility, once saying: “A producer is not just a bookkeeper, or a banker, or a background. He makes the picture… If the film is a failure, I am responsible. If it is a success, then it is a joint contribution of the actors, director, writers, set designers, musicians and script girl — everybody except the producer. This is a fact of life; I do not complain.”

For his passion, indefatigable humour and lack of pretence, he remains an example to anyone in the arts — a genre-hopping barbarian, pint-sized strongman, serious clown and dreamy realist who flew both ways between the Italian coast and the Hollywood Hills. “Cinema”, he once suggested, “is something you have to love with your guts. Otherwise, forget it. It demands 100 per cent of your attention. But it’s the biggest toy that adults have, and that’s why it will never die.”

This article originally appeared in Issue 61 of The Rake.