Travel Journal: Venice

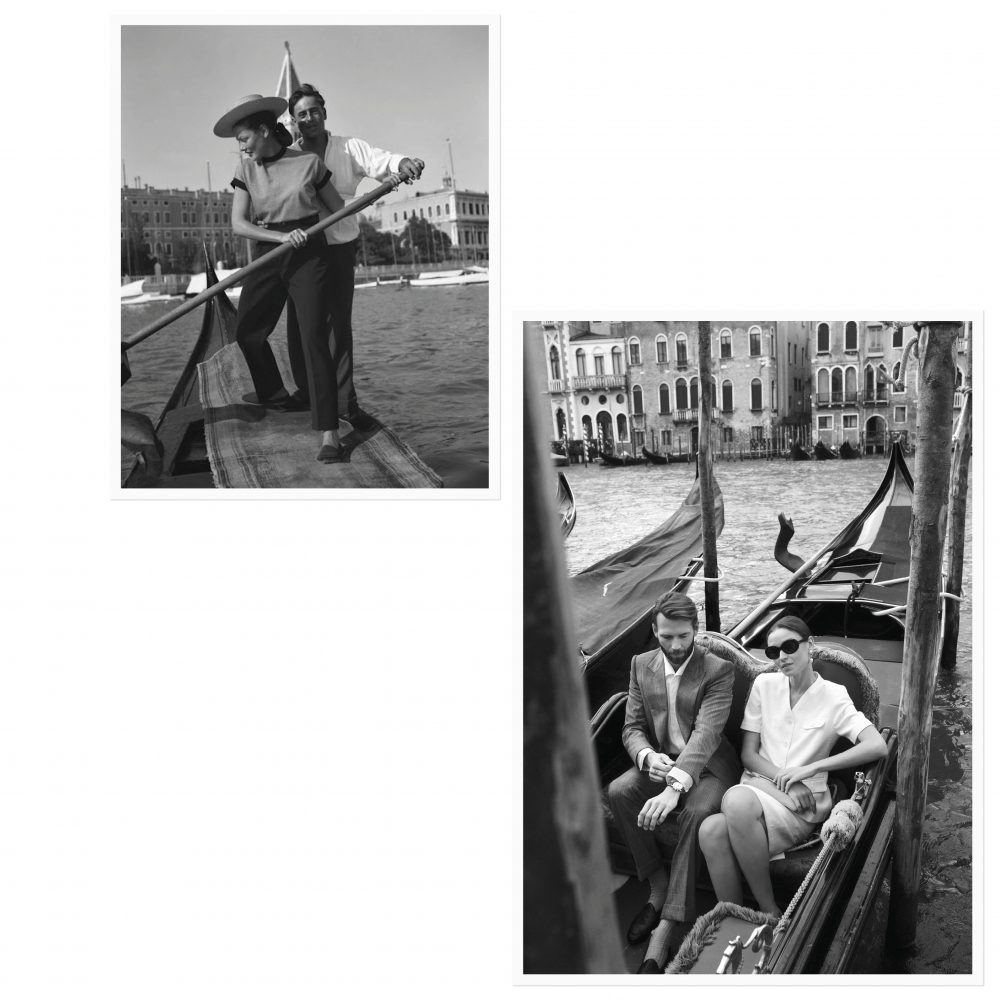

It begins with a gondola—as it ought to in Venice. In the early morning hours, while the sun yawns out into the open lagoon, the small boats skate vertically above the water and life restarts in the world’s most beautiful city.

For those of us on land, Venice is a hard place to navigate. The streets offer innumerable dead-ends and paths that lead to the water, forcing visitors to backtrack and resort to mental compass-bearings. North. South. (Where is the Grand Canal? Is it that way?) OK. Go East, follow the path. Turn West. You might arrive at your destination.

We had heard news of a popular and authentic spot to grab cicchetti—that Venetian pintxo slice of crusty bread topped with mammoth portions of seafood, cheese, and ham. Osteria al Squero is a hole-in-the-wall packed with students from the nearby university, as well as the city’s writers and painters. It’s also—a good sign—a place where the dominant language one hears is Italian, and even better, in the cursive Venice dialect. We ordered a spritz Select, the original version of the spritz drink, which sits between the sweet and bitter flavours of Campari and Aperol and slightly boozier, so that after two, the already dreamlike surroundings of the city become pleasantly deranged.

On the other side of the canal, we spied a boatyard. “That,” our gondolier mentioned to us, “is where they repair the gondolas. There are two Tyrolean homes, do you see?” In the foreground, wooden-log buildings, more Alpine than Venetian stand out like flies in a glass of milk. They are not meant to be here, but their presence among the spires and Moorish windows marks another cultural irregularity in Venice’s architecture. The story goes that many of the artisans who crafted the gondolas were brought in from the Tyrol region of northern Italy—setting up shop, they built their own homes to match those of the beloved Alpine villages.

The famous Harry’s Bar was an appropriate port-of-call for a drink after lunch. This is where the Bellini and the Carpaccio were conceived by founder Giuseppe Cipriani, and the small, honeycomb bar became increasingly more famous under the stewardship of his son Arrigo (who was meant to be called Harry, but because of strict rules in the facist Italy of the time, settled with something near enough).

In good spirits, we departed to shop at the city’s little nooks and shops. Venice is full of treasures still crafted in the traditional way, and Giberto Glass makes the finest Murano glassware—which is itself among the best in the world. It is run by Count Giberto Arrivabene, the dashing aristocrat who resides on the top-floor of the Palazzo Papadopoli. There are also elegant furlane slippers to be found at Piadaterre by the Rialto: the original address to find the gondolier shoe (which actually looks rather chic when paired with your cotton or linen tailoring).

“Tomorrow, we’ll make an effort to see the Tinoretto’s at San Rocco,” we promised. “Then we’ll sit at Florian’s in San Marco’s Square before exploring Peggy Guggenheim’s collection at the museum.” Plans must be made in Venice ahead of time. There are so many things to see and to do, and the day disappears as the endless distraction of the city’s beauty slows one’s pace, and brightly lit restaurants invite one to spend hours and hours inside eating lagoon crab, clams, or vongole spaghetti.

There was Alla Madonna, tucked into an alleyway by the Rialto. Since the early 50s, visitors have arrived to try the seafood and their sweet tiramisu (indeed, it is a candidate for the dessert’s origin). On the Lido, we sat beside the directors and film critics at Trattoria Andri. The dish to order here is the octopus prepared in its own ink, with a slice of polenta—a must-have when in Venice. “But nothing makes a Venetian happier than tramezzino!” remarked our gondolier. These small Italian finger sandwiches can be found all over the city, crammed with prawns, salamis, and eggs; favoured by all walks of life. If you walk into Bar Tiziano, you will notice off-duty gondoliers resting by the steel bar, picking a selection of tramezzini to enjoy with a draft beer or a glass of wine.

Couples walk home from their ‘Giro d’ombre’—or wine stroll. The tavern-like bacaros have a bustling atmosphere, whether you decide to visit the friendly Osteria Al Pugni or the Cantine del Vino gia Schiavi, where all customers are encouraged to drink and eat standing up; a pit-stop before the next, and then the one after that. It’s a myth that Venice is a giant tourist-trap. If you scratch the surface, turn away from the Grand Canal, real and authentic spots become easily accessible. The hip neighbourhood of Cannaregio is all the more inviting for the canal-sides that are lined with bacari, serving delicious food (our pick is the iconic Paradiso Perduto—seafood platters aplenty) and flavoursome Veneto wines. But a few short turns away from the Rialto, and the dusty tavern signs once again invite us in for something to eat or drink. Venice is a city that mixes its own grand opulence with down-to-earth sensibilities. Sure, the central streets are flooded with tourists—and consequently, overrun restaurants and gift shops bait the naive visitor. But as the writer Italo Calvino once wrote about Venice, “...you take delight not in a city’s seven or seventy wonders, but in the answer it gives to a question of yours.” If you intend to discover the real Venice, the answer will meet you in the beauty of its museums, canals, and softly-lit trattorias, and the resurgence of a new creative spirit that resides merely a skip-and-a-hop away from its major attractions.