‘When Someone Looks At A Portrait, I Want Them To Feel Engaged - Like They're In a Conversation’

I’ve had quite a long relationship photographing both the King and Queen. I started photographing Camilla Parker Bowles about five years before she got married [to Charles, in 2005]. She then asked me to photograph their wedding. That led to him quite liking what I’d done at the wedding, and he asked me to take some pictures of him only. Then he asked me to photograph the boys, so when William got married, I stepped in there and did that. It was a sort of progression rather than suddenly overnight.

When someone looks at a photograph I’ve taken of somebody, I want the viewer to feel engaged with that person, almost like they’re in conversation with them. Which means that you, as a photographer, have to art, a passion, whatever it was — to fall back in love with it, although I didn’t think I’d ever fallen out of love with it. But this camera reignited what I used to feel when I used the Hasselblad. When Fujifilm realised there wasn’t going to be quite such demand for film, they put their work toward the task of creating a digital camera that is really interesting. This camera was basically designed and created by people who love photography and film, so it came from a completely different place from many other digital cameras. There’s so many little details we need to be fully informed on beyond just photography. For an example, what angle should one photograph not just the line, the cuff, the suit, the light — whatever — I’ve got to try to get an emotion into that picture as well. And if I can capture that emotion, then you, as the viewer, hopefully will pick up on that for each occasion. At the same time, it’s important, you know — we’ve got quite a big occasion coming up, but I don’t want to be any different to what I normally am, because so many other things have changed, including the king. But if he walks into the room to have his photograph taken and I’m suddenly not the human that he knows, that’s going to be unsettling and it’s going to be different and we’re not going to get this emotion through the lens because he’s going to be thinking, Who’s that, I thought we got Hugo. It’s quite difficult to move around [central] London on the day [of the coronation]. So me and my team are going to cycle to the palace in the morning and we’re going to stay in the palace all day. The throne room is going to become our second home.

There are a few favourites [of mine] over the years. Some of them are very private, as in they haven’t been seen by the public. Actually, the first photograph I ever took of the King and Queen together is one of my favourite photos; I sent it to him recently, just reminding him of it. It was when they walked down the aisle in St. Georges chapel having just got married - (Charles) is so happy and he is beaming like you’ve never seen before, and [Camilla] is looking very beautiful. I had the luck of the wind just catching in the coat and the dress, and whatever. It’s just a moment, and I was so lucky to get that picture. But as for more public ones: on his 60th birthday, the portrait then, I love that because we’d done a shoot, the pair of us had done a shoot, photographing him in various uniforms, and we decided to do one that we referred to as the “for-the-hell-of-it” picture at the end of the shoot. I referenced a painting I thought was a John Singer Sargent painting, but actually it was a Tissot painting of Frederick Burnaby. We discussed it and then did our own version of it, which was sitting on a chair like this, with his arm up, and you get the stripe of the trousers.

There’s so many little details we need to be fully informed on beyond just photography. For an example, what angle should one hold a sceptre at, and what does it signify — do you hold it this way or that way? Also, there’s a technical exercise going on, which I really like — the series of photographs we’re going to take are telling a story, as well as being of the moment. It becomes like theatre, because when we’ve created these little scenes in our head and we put them on paper, it takes about three days to set everything up and test it. Then we do a dress rehearsal with stand-ins, and we [time] it so we know exactly how long it’s going to take. We know with any good theatre that if something goes wrong you need all the players to be able to accommodate and ad-lib, so we do practise things going wrong.

The last coronation portrait photographer, Cecil Beaton, was a great man, great photographer, ahead of his time. We now look at the imagery and think that it illustrated the time. At the time, I think he made a few people sit up with what he’d done. I think it’s important to play your own game, the game that got you there in the first place. I think it’s a bit risky to start changing too much, but that doesn’t mean to say that I’m not looking for any opportunity just to even up our own game and do something that might make people sit up and say, “Woah, O.K.”

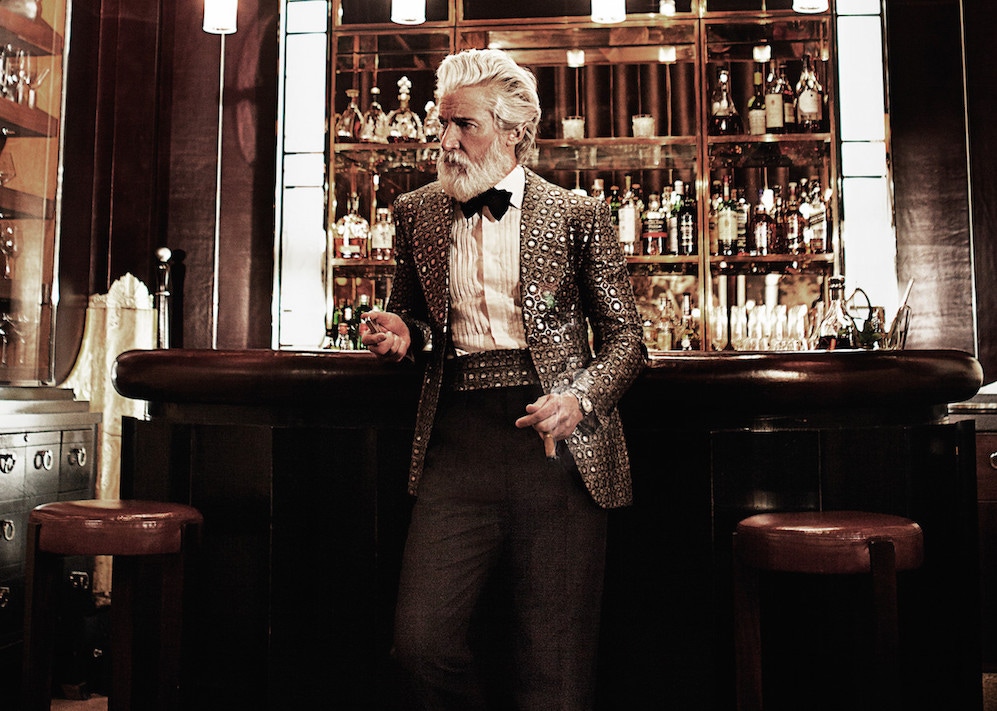

Location courtesy of Mark's Club

Read the full interview in Issue 88, available to purchase on TheRake.com and on newsstands worldwide now.

Subscribers, please allow up to 3 weeks to receive your magazine.