Words of Wisdom: Robert Ettinger

Robert Ettinger, the Chairman and Chief Executive of the eponymous luxury leather goods brand, tells The Rake how, despite changing times in the industry, he continues to build on his father’s founding legacy.

The idea of the family business is an evocative notion, and one that holds plenty of kudos in the luxury goods industry. Hefty price tags imply that handiwork and great care has gone into a product’s creation, yet this is not necessarily the case with large corporations who may boast prestigious names yet proffer mass- produced wares that rarely live up to customers’ expectations. Family- run businesses tend to be the antithesis of this. In the best ones, the focus is often less on the bottom line and more on quality and integrity. And then there’s the romance of the family business, how the company is passed through the generations, each time evolving subtly when a more youthful member steps in. Ettinger is one such brand, and, well into its eighth decade, continues to set the benchmark for handcrafted, meticulously detailed leather goods.

Founded in 1934 by a charismatic man of the world, Gerry Ettinger, his eponymous brand would quickly become a byword for quality. It has sourced, tanned and manufactured each of its products in Britain. Although based in London, Gerry had spent years travelling the world and had built up an exhaustive list of contacts that would serve him well in the early years of the brand. It was, though, his eldest son, Robert, who ensured Ettinger received an illustrious seal of approval. Fifty years after its founding, Robert Ettinger stumbled on an article in a newspaper discussing the process companies have to navigate in order to receive a royal warrant. Like a man possessed he worked on attaining one for the firm his father founded, and in 1996 his wish was granted by the Prince of Wales, thus permanently cementing the quality and excellence the brand had become known for. Today, Ettinger are evolving further, focusing much of their attention on their rapidly growing online business, which has allowed them to reach younger customers in more places. The Rake discusses with Robert how this most quintessential of British heritage brands stays relevant in the ever-changing sphere of luxury...

It was about seven years ago when we thought we’ve got to start selling online. We could see it was happening and we built our first website. It wasn’t at the beginning of online luxury selling, but it was pretty near. Today we have our own photographic studio and a full-time photographer, taking pictures of everything — we’ve decided to do it as well as it can be done, and it’s working really well for us. We get orders every day from people all over the world, countries we haven’t even heard of. We don’t know how they see us. I think people trust the brand, and having a royal warrant helps, they buy because of that and they’re happy to spend a lot of money on a product without ever seeing it.

You need to interact much more with people, particularly online. You’ve got to make it feel like you’re in the Ettinger world. It’s quite exciting, we have lots of new people in the company in their twenties, they’re much more savvy, they bring energy, they’re quick to learn. I understand it, but to me it’s amazing — it’s only been 21 years since online commerce first became a thing, apparently. It isn’t that long ago when Amazon started and sold only videos and books, and look at it now.

We’re proud of having a royal warrant, but we don’t boast about it. We’ve got it because we make leather goods for H.R.H. the Prince of Wales — it is a seal of approval, of trust and quality, and we are allowed to put it on the product and the packaging. It helps us enormously. I think if you look at a list of royal warrant holders, it’s everyone from Corn Flakes... [to Bentley]. But for us it’s a very important part of the business.

Firstly we were made in London on St. John Street, Smith field, which was traditionally London’s leather area. The tanneries were all on the river, yet they disappeared around 80 years ago. A number of streets were named after tannery operations, and we were the last ones on St. John Street, about 20 years ago, but it became gentrified and turned into of offices and restaurants. I remember as a kid going there, and it was a fantastic place. The pubs opened at 4.30/5 in the morning, so that when the [workers] came off shift they could go and have a few pints at lunch; it was amazing, there was a real atmosphere. That’s gone, obviously, so what we did about 17, 18 years ago — we knew we couldn’t stay in London and grow so we bought a much bigger factory in Walsall, just north of Birmingham, which is the leather town of England.

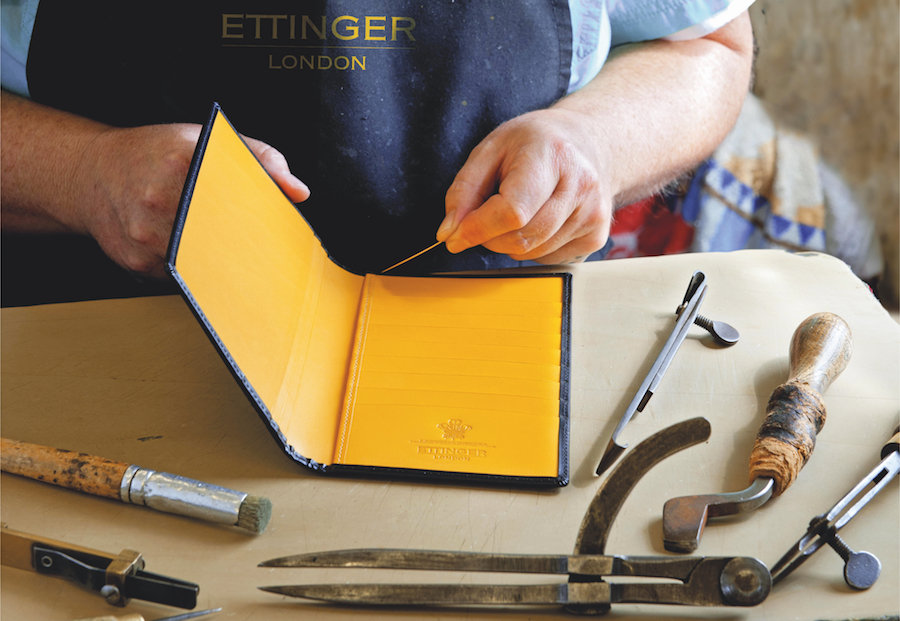

The factory was home to a company called James Homer, which had been making leather goods since 1890, and we’re still in the same factory that was built in 1890 — it’s a long building with lots of windows so you can work by natural light. We refurbished it a lot, but it’s the right sort of building for making products where you’ve got to have a good sight of what you’re doing. The factory is fascinating — the films on our website show some of them, but to go there and see some of these people and what they’re doing, some of them the second or third generation, crafting a wallet or a notebook — I couldn’t do it!

My father’s legacy is important [to the company], although other people seem to think it’s more important than I do, because [to me] he was my dad. He was very fair on me, he didn’t say I had to come into the business as soon as I left school, he let me travel the world and work for other companies and then indulge my passion, which was skiing — I taught skiing for some years. In my late twenties he said you’ve got to make a decision: either you continue gallivanting or you come and do something. So I said, O.K. He remained in the business until he was 92 — not that long ago — and he loved business. He spoke six languages — he could go to Spain, Italy and Germany and converse with the [people at] these factories, who had never sold abroad before. He was a very clever businessman and I have a lot of respect for him.

When I was an apprentice in Germany for a year and a half for a luxury firm, he used to come over on weekends and I’d travel around trade shows with him seeing how he operated, and it was great. I’d live the high life for a few days and then go back to my digs. I think travelling and experiencing different cultures is very important when it comes to running a business. I come from an international family with different backgrounds and they all travelled a lot and I inherited that. But whenever we start selling in a new country, I like to read about it and go there because to find the right partners doesn’t happen just like that, you have to go there and meet people and talk to them. You have to understand it, the etiquette and manners. Country to country the way they do business varies, and understanding it helps a lot.

We’re not a high fashion brand. We do have a couple of very good freelance designers who’ve worked for a number of big brands, but a lot of what we do is done in-house; we’ve got photographers who’ve got that flair.

What you can do is innovate with leather and colours. We were thinking about British men’s shoes, and what’s typical of them, and the idea of ‘brogueing’ came up. Normally when you make holes in leather you have a metal punch, or multiple punches. But you can’t make a metal punch that makes holes as small as we wanted, it’s physically impossible, so we found a laser machine to make incredibly fine holes, backed it up with this leather to give it the colour behind, and that’s the new collection. From this angle you can see the yellow and then... it disappears. It’s little touches like that that ‘Ettinger-ise’ it.

I’m always in our London office by 7am. I live in the country so I drive into London, and at 6am I go swimming just across the river, every day. Then I’m in here early, so I have two hours where nothing’s going on. I have a dictation machine in my car, so when I get in I have six or seven notes on that — I write them down and prioritise what I’m going to do that day, that week, that month. And when they’re done they get ticked off. As we grow, there are more and more things. It is juggling, and they say men can’t multitask, but I’ve learned. I think it’s something I can do. I like doing a lot of different things. In fact, if I was doing just one thing I’d be bored. I have a low boredom threshold; I like doing lots of different things.

This beautiful portfolio case has compartments for A4 papers, smartphones, wallets and credit cards.

This beautiful portfolio case has compartments for A4 papers, smartphones, wallets and credit cards.

This beautiful portfolio case has compartments for A4 papers, smartphones, wallets and credit cards.

This beautiful portfolio case has compartments for A4 papers, smartphones, wallets and credit cards.