Fight or Flight

The Flying Flea’s contribution to the war effort was small but significant. The name has finally been revived, and the bike — Royal Enfield’s first electric model — is ready to do battle in the urban jungle.

The D-Day landings of June 6, 1944 could never have succeeded without the plethora of military machines that helped get boots on the sand in Normandy and onwards into occupied France. As RAF Dakota aircraft dropped an estimated 7,000 British parachutists, ground troops piled out of landing craft onto the 50-mile stretch of beaches codenamed Omaha, Utah, Gold, Juno and Sword, while vehicles ranging from Churchill tanks and Bren gun carriers to Daimler Dingo scout cars and hundreds of examples of the ubiquitous Jeep delivered Allied troops into the heat of battle.

But among the many better-known types of motorised transport, there was also a largely unsung hero: the diminutive ‘Flying Flea’ motorcycle built by the British manufacturer Royal Enfield.

The smallest bike ever made by the marque, the Flying Flea’s roots can be traced back to a machine made during the 1930s by (ironically) the German firm DKW.

DKW’s RT98 model had been imported to the Netherlands by a Jewish-owned company, but in 1938 the Nazi party’s antisemitism led to the import concession being banned. The Dutch subsequently looked to Royal Enfield to build a copy of the bike in England — but instead of replicating the original’s 98cc engine, the Enfield version used a larger and more powerful 125cc unit.

No sooner had the designer Arthur Bourne completed his work than war broke out, and the battlefield potential of the bike the military dubbed the Flying Flea became clear.

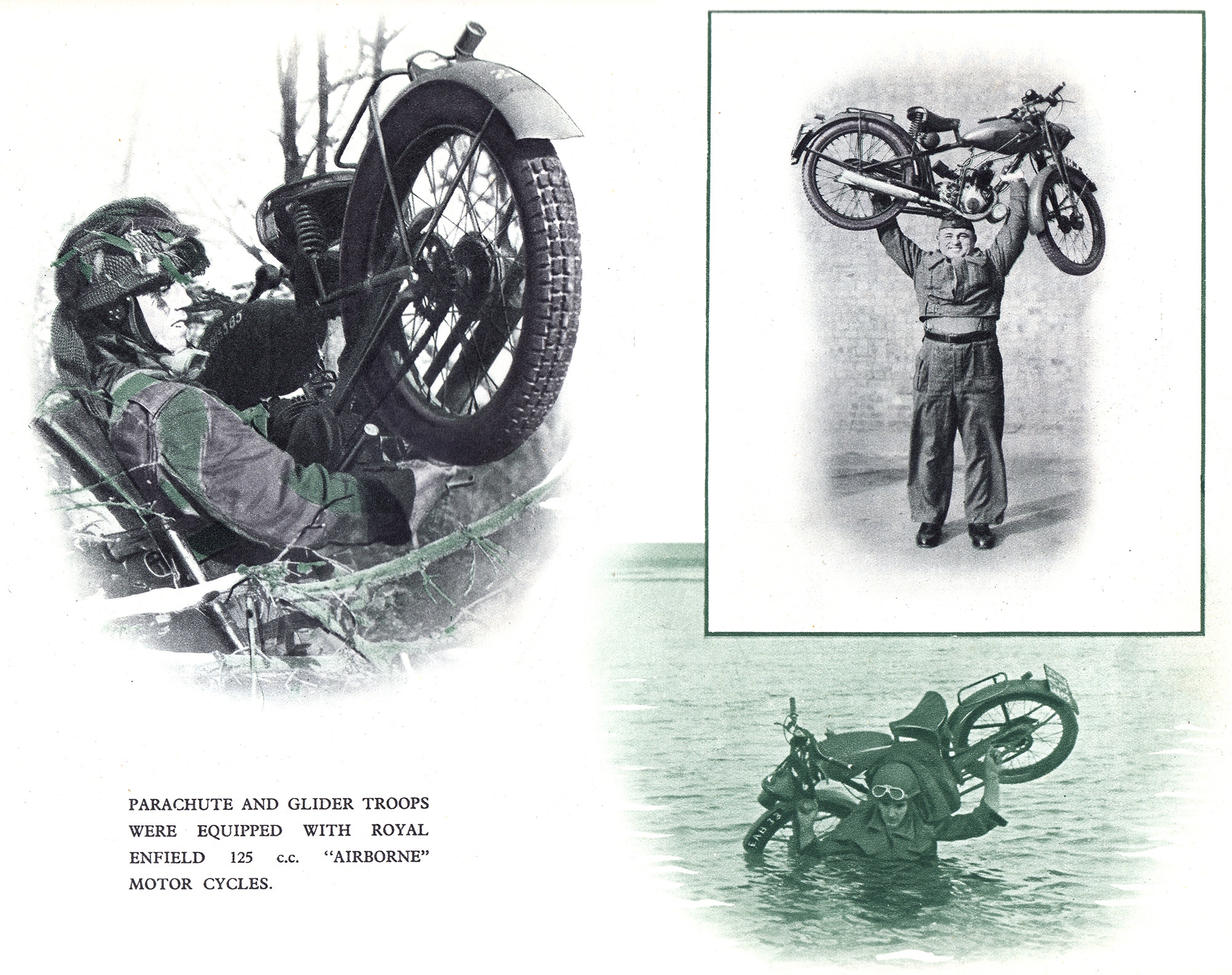

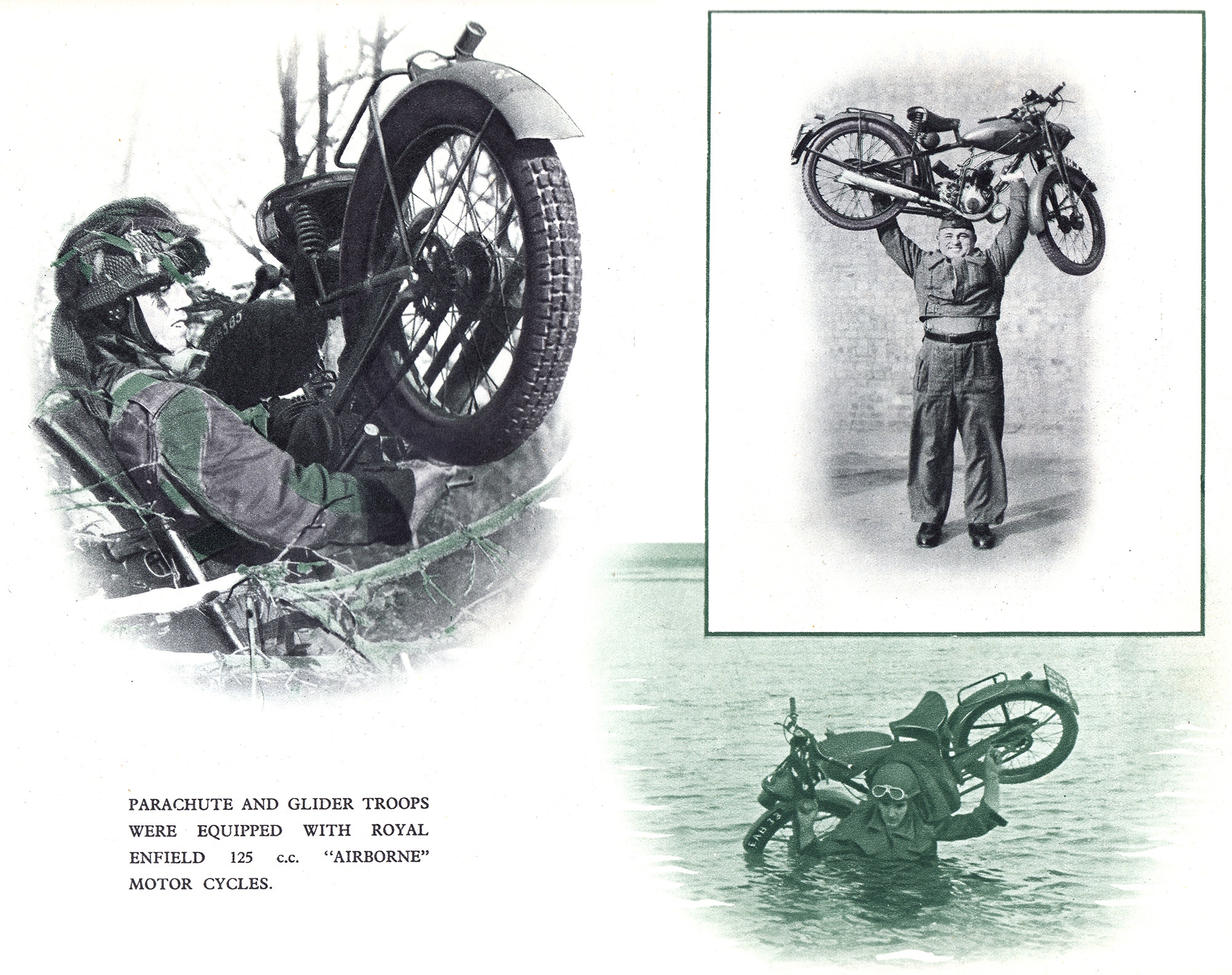

But it wasn’t until 1942 that the War Department ordered 20 examples of the civilian model R.E. for evaluation, after which it called for modifications that reduced exhaust noise, relocated the tool box from the bottom of the frame to beneath the seat, substituted the standard Amal carburettor for a Villiers item, and added more powerful Miller lighting.

Once the Flea was deemed up to spec, work began on the device that would lead to its ‘Flying’ prefix: the development of a tubular steel cradle within which — with its special footrests, kickstarter and handlebars folded — the bike could be securely contained so it could be dropped from the bomb racks of Halifax and Lancaster aircraft.

However, the initial plan, to parachute Flying Fleas into battle, was soon superseded by the idea of sending them to their destinations four at a time inside troop-carrying gliders. In addition to disgorging them from landing craft, that was the method used to get large numbers of the machines on the ground during the Normandy landings, so they could be picked up and used for ‘rapid advance’ by parachutists.

Sufficiently powerful to tackle rough ground and long distances (but also light enough to be carried across impassable errain), the Flying Flea’s one- and-a-half-gallon fuel tank was large enough to supply the efficient two-stroke engine for almost 250 miles. With their drab olive paint jobs, hooded headlamps and muted exhaust pipes, Flying Fleas also proved useful as despatch bikes for relaying messages between airborne units and assault troops, as well as to units that found themselves out of radio contact.

Flying Fleas remained in use by the army for a short while after the war ended in 1945, with surplus examples repainted and sold into the civilian market, where they served another vital role as a cheap and efficient means of getting Britain moving again.

Until recently, though, the story of the Flying Flea’s contribution to the war effort had been largely forgotten.

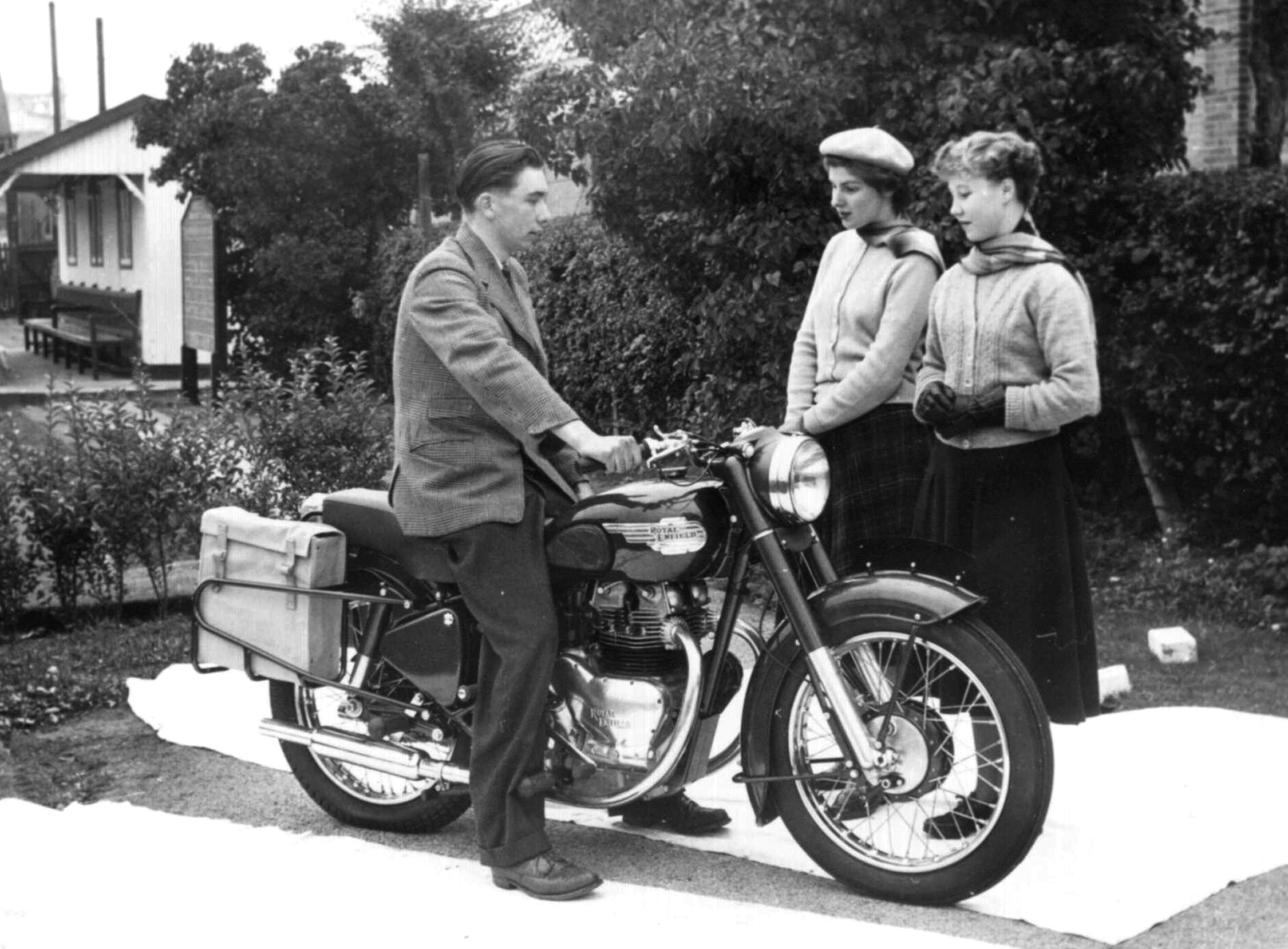

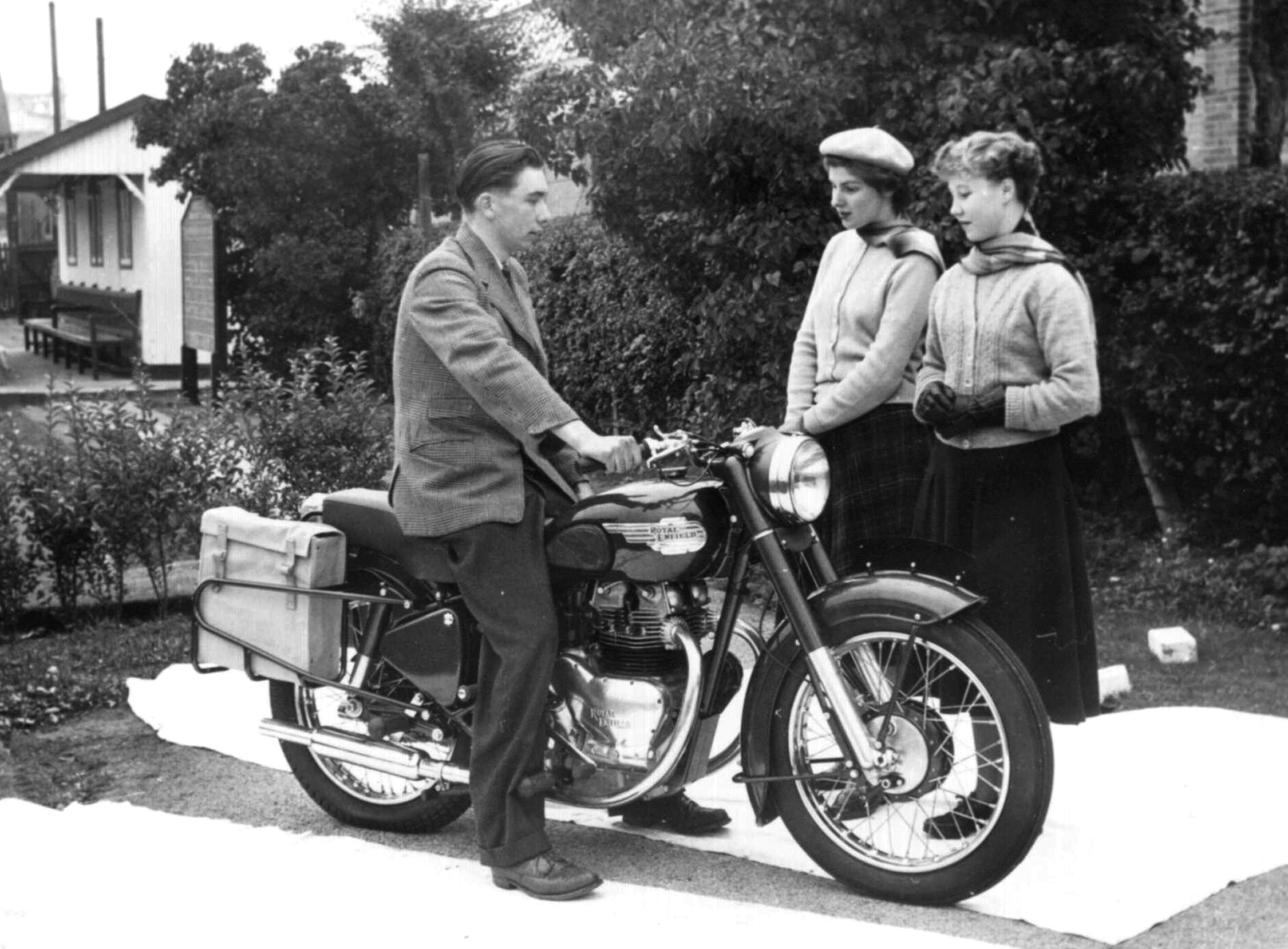

In 2018 the modern-day Royal Enfield firm created a limited edition version of its celebrated 500cc Bullet, which it named Pegasus, after the distinctive claret and blue ‘Pegasus flash’ insignia designed by the self-taught artist Major Edward Seago and worn on the arms of all airborne forces.

Royal Enfield worked with the Parachute Regiment on the design of the Pegasus in order to incorporate cosmetic features of the Flying Flea into each of the 1,000 machines being built. That meant serial numbers handpainted onto the fuel tank, wartime service colours of olive drab and service brown, a blacked-out exhaust system, period-correct handlebar grips, and military-style canvas panniers. The edition sold out quickly, and pre-owned versions have become highly sought after.

Now, however, the ‘Flying Flea’ name has been revived to designate both a new Royal Enfield sub-brand and a new motorcycle that’s set to hit the streets in the spring of 2026. But, unlike the original, the new Flea won’t need to have its exhaust noise suppressed, because it will be electrically powered and almost silent in operation. This version of the Flea is designed to battle urban traffic rather than enemy forces, and is being billed as offering “agile, exciting and accessible city mobility”.

The 21st century Flying Flea is Royal Enfield’s first attempt at an electric motorcycle. It is said to take inspiration from the wartime model, and will be available in classically styled C6 and scrambler-styled S6 versions.

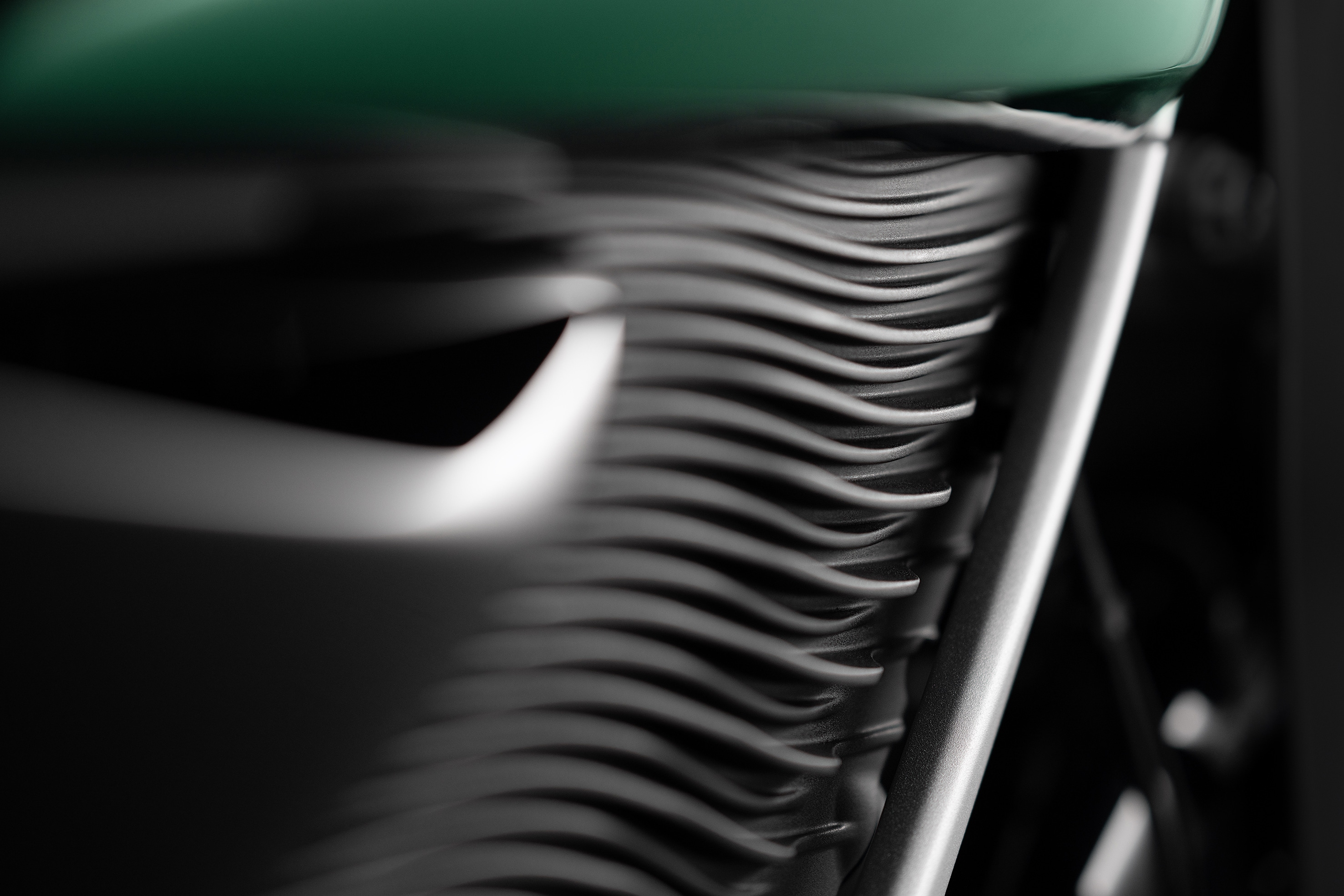

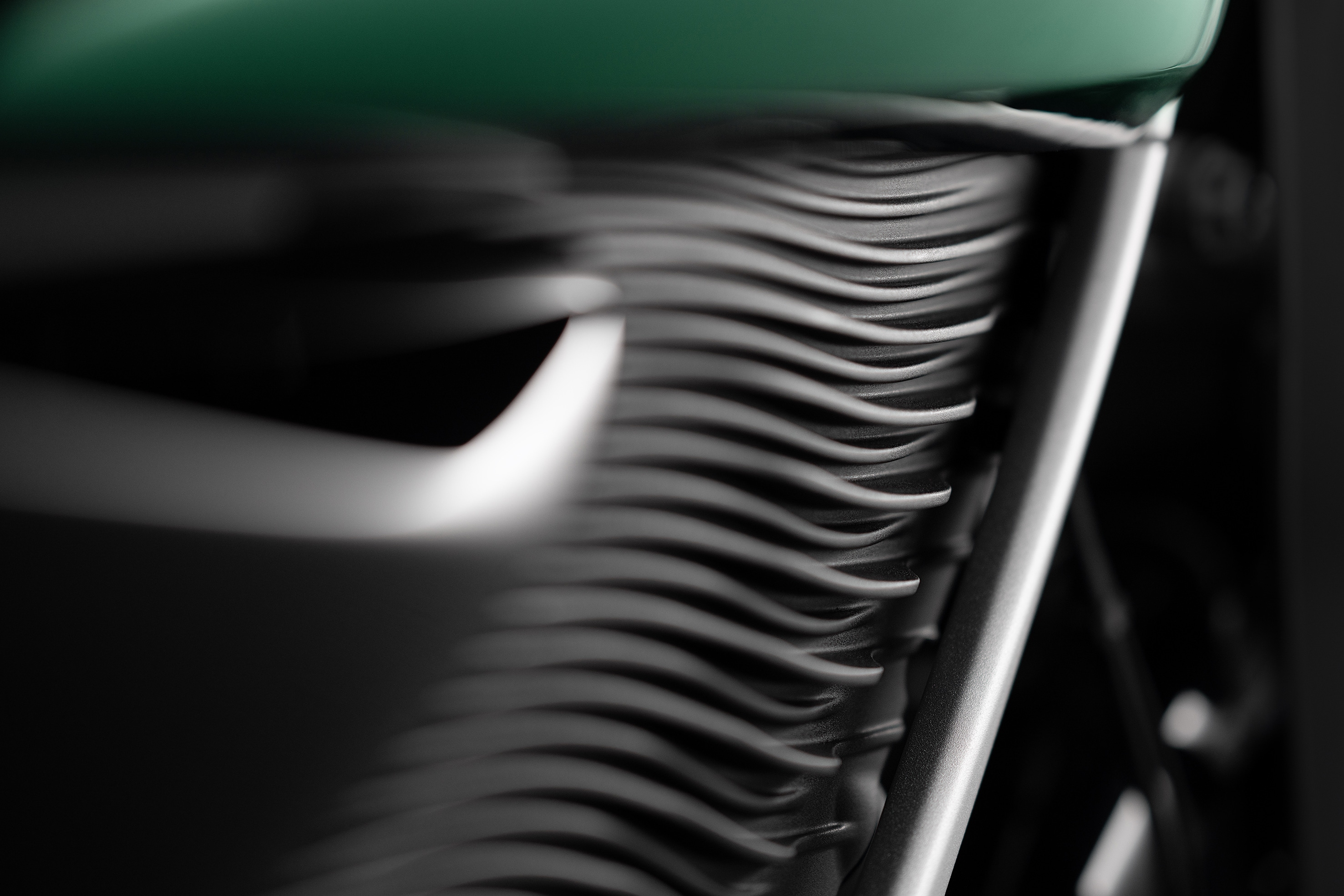

The bikes will be instantly recognisable by their unique front suspension system, which is a modern-day reimagining of the ‘girder’ fork set-up used on the 1940s Fleas that made them so suitable for crossing difficult terrain. The new version of the system is, like the bike’s frame, cast from lightweight aluminium combined with a finned, magnesium casing to house the battery pack.

Royal Enfield say the new bike will feature so much cutting-edge E.V. technology that they have filed 28 patents during the past six months alone. Features include bespoke software that constantly monitors the Flea’s electrical system, in order to provide optimum range and performance as well as to enhance the riding experience. A unique Vehicle Control Unit (V.C.U.), meanwhile, is said to enable more than 200,000 different combinations of riding mode. It is designed for over-the-air updates and will alert the owner if the bike is disturbed or moved unexpectedly — with all systems remotely operated by smartphone app.

It all sounds impressive, for sure. But as a motorcycle fan who is shamelessly stuck in the past, I’m far more moved by the idea of hunting down an original wartime Flea, loading up my canvas panniers and heading to the Normandy beaches with the legendary words of the great Sir Winston Churchill echoing around my head: “We shall not flag or fail. We shall go on to the end. We shall fight in France, we shall fight on the seas and oceans, we shall fight with growing confidence and growing strength in the air. We shall defend our island, whatever the cost may be. We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills. We shall never surrender!”

That counts for Fleas, too...