HOW A PEASANT VILLAGE ROSE UP: Gstaad

In little more than a hundred years, the Swiss town of Gstaad turned its cowsheds and timber yards into deluxe hotels and boutique apartments — and in the process became a winter toy town for the jet set. Orginally published in Issue 67 of The Rake, Nick Foulkes writes, don’t let that mislead you, for time still moves mysteriously through this charming alpine hideout.

“The great majority of tourists visit Switzerland between the middle of July and the end of September,” observed Baedeker’s Guide to Switzerland in 1895, adding that if one were of a botanical bent and wished to “see the scenery, the vegetation, and particularly the Alpine flowers in perfection, June is recommended as the most charming month in the year”.

The quaint tone of voice evokes the novels of Henry James and Edith Wharton, men in tweed knickerbockers and Norfolk jackets, and women sensibly attired in bonnets and walking skirts, their corseted waists in inverse proportion to their billowing leg o’ mutton sleeves, striding across sunlit alpine meadows taking lungfuls of crisp Swiss air and surveying distant snow-capped peaks. Baedeker’s 1895 guide to Switzerland ran to 500 densely printed pages of advice, pull-out maps, hotel prices, itineraries, railway timetables, and so forth: in short, everything the late Victorian traveller could have wanted… unless they happened to be planning a trip to Gstaad.

For a start, Baedeker spelled it Gstad, and gave it a mention for which the word ‘fleeting’ implies way too much detail. Skip a line on page 250 and you would have never known the place existed; it is mentioned only once, and only then inasmuch as it found itself “at the mouth of the Lauenen-Thal”. That is it. And so, guided by Baedeker, those Henry James and Edith Wharton characters would have passed unheeding through what would become one of the world’s most famous resorts, heading instead for the picturesque Lauenensee, there to pick and press alpine flowers or sketch the lakeside landscape. If anything, the “finely situated” and almost homonymous village of Gsteig was the local tourist hub.

To be fair to Baedeker there was not much to detain its readers in Gstaad. A photograph from around 1895 shows a scattering of wood-sided houses and farm buildings, along with huge, geometrically exact (this was Switzerland, after all) stacks of logs. Along with rearing cattle, the chief economic activity of Gstaad was timber production. And thus things might have remained, but on the night of July 18 and 19, 1898, those wood-sided houses, farm buildings and piles of logs went up in flames that razed most of the modest settlement. It was almost as if Gstaad had never existed, and but for the lobbying of the local sawmill owner, the railway would have passed by the blackened ruins. But thanks to his persistence, on December 20, 1904 the railway reached Gstaad and the village began its phoenix-like rise to greatness.

During the first years of the last century, the fad for winter sports was beginning to catch on. Sleepy Gstaad became a bona fide resort boomtown. Within a few years of the railway arriving, there were 1,000 hotel beds, and even then demand exceeded supply, with disappointed would-be guests being fobbed off with accommodation in the now less glamorous Gsteig.

By 1913 even Baedeker was obliged to admit that “the advantages of the alpine climate are not limited to the summer months, but the benefits of spending the winter in the Alps have only recently been widely acknowledged”. Gstaad was already several steps ahead: the winter season of 1913-14, from December 8 to March 5, saw the opening of the Gstaad Royal Hotel and Winter Palace. Executed in an architectural style best described as Walt Disney baronial, for more than a century the benign silhouette of the Gstaad Palace has watched over the village, as Gstaad gradually turned its cowsheds and timber yards into apartment buildings and luxury boutiques.

As the Gstaad Palace is one of my top five hotels on this or any other planet, I might be exaggerating a little, but those 88 days of its first season changed the world, for if you were rich and social, you now had to add Gstaad to Monte Carlo on your list of destinations. In fact, Gstaad did its best to bring the Riviera experience to the mountains: when the Palace opened a pool in 1928 it imported sand so that guests could feel like they were on the Côte d’Azur.

As well as the opening of the legendary Palace hotel, the other seismic social event to shape modern Gstaad took place in 1917, when pupils and teachers of Le Rosey — think Euro-trash Eton (but for rich people) — spent their first winter season in Gstaad, a tradition that persists to this day; it has bred generation after generation of return visitors, scions of the world’s leading royal, imperial, industrial, financial and oligarchic dynasties. It must be one of the few educational establishments of which the director also occupied a seat on the board of the local Palace hotel — as happened during the 1980s and 1990s.

But part of the charm of Gstaad is that progress treads carefully here: well into the 1950s guests at the Palace were collected at the railway station in a horse-drawn sledge. And Gstaad was still recognisable as what the American economist, diplomat and intellectual J.K. Galbraith, who came to live here in the mid 1950s, described as a “peasant village, where small lumber mills [which still survive] sawed the huge straight logs that are brought down from the surrounding mountain forests”. Still, as peasant villages go, it was the sort in which Marie Antoinette would have felt right at home.

A black-and-white film of life in the resort in the early 1950s shows dignified men in tweeds and plus fours enjoying the sport of curling; in another sequence, some daredevil sportsmen attach themselves to horses and race through the snow on skis, acting out a sort of invernal version of the Roman chariot race. But skiing aside, life was leisurely. Guests booked into the Palace not just for a week or a month but the entire season, arriving before Christmas and staying until the end of March. They had their own tables in the hotel grill room and would get plenty of use out of their dinner jackets.

On the whole the après-ski was commensurately sedate. One of the more famous post-war winter visitors to Gstaad was Field Marshal Lord Montgomery, who took a chalet and could be seen dangling from the precarious timber-framed chairlift that opened in 1946 wearing the beret that had been his defining sartorial feature during the war. His dinner parties were famous not for their riotousness, but for the military punctuality with which they came to a close, ending at 10pm precisely with the host’s observation, “Gentlemen, the night was made for sleep.”

Back then, if the youth felt like ‘throwing some shapes’ on the dance floor, Monsieur Leroy used to take afternoon dance classes at the Palace, where the younger guests learned to do the cha-cha-cha; his wife ran bridge evenings. As the women played bridge, the Greek tycoons would fill the hotel lobby with the rattle of dice as they played high-stakes backgammon.

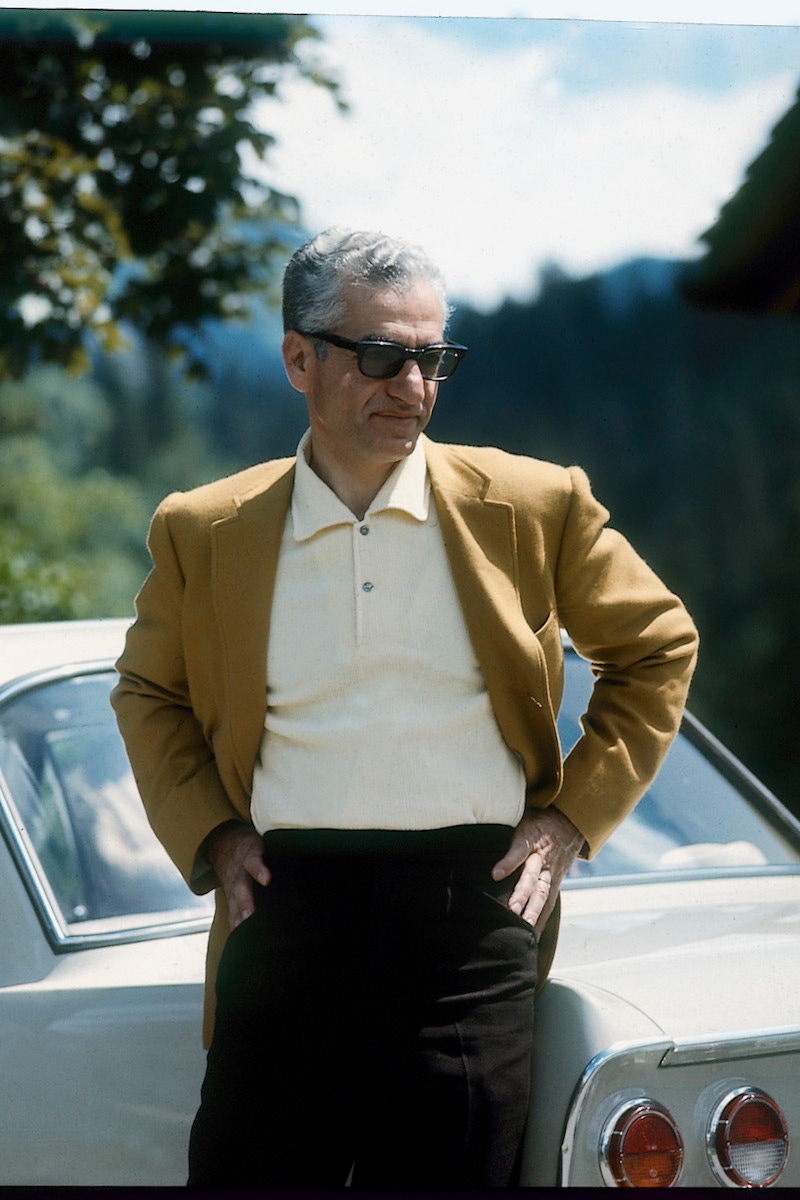

In the 1950s the Greek shipping tycoon was as much an archetype of affluence as the oil-rich Arab of the seventies and eighties, the Russian oligarch of the nineties and noughties, and the Asian billionaire of today. Gstaad had acquired its Greeks during the second world war, which had found many of them living in Lausanne and Geneva, and the resort remained popular with Peloponnesians in peacetime, too. Grand shipping clans, such as the Goulandrises, would take half a floor of the Palace hotel, and among the younger generation was Taki Theodoracopulos, the man destined to become the 20th century’s most famous Greek, who first visited the Palace as a teenager in the summer of 1956 to play in a tennis tournament. Like so many he fell in love with the mountain village, and is still to be found there.

Taki was one of the great ornaments of the Eagle Ski Club, which opened at the top of the Wasserngrat mountain during Christmas 1957. Just as the world’s cold war superpowers were involved in an arms race, and then a space race, so through the golden age of the jet set Gstaad and St. Moritz were locked in a struggle for supremacy. St. Moritz, which is higher than Gstaad, had hosted the winter Olympics in 1928 and 1948, and it also boasted the Cresta run and the famous Corviglia Club, to which the Eagle was Gstaad’s riposte.

The Eagle’s opening made news around the world. “Gstaad is playing for top stakes in the Swiss tourist trade… An alpine toy-town Gstaad is trying to make chic St. Moritz look like a redbrick suburb,” the London Evening Standard reported. “Gstaad is so expensive you feel that the snow you are walking on has been specially imported.” Under the headline ‘Skis and jewellery’, another newspaper report described it as “designed to be a social rival to the Corviglia Ski Club at St. Moritz. This has previously held the monopoly as the mountaintop meeting place of the world’s most publicised if not most prominent personalities — even if they are not publicised for their skiing.” London’s Sphere newspaper agreed. “The purpose of the club is to attract the most exclusive social gathering at the famous winter sports resort, rather than to provide facilities for the serious devotee of the sport of skiing,” it noted tartly.

Opinion on the architectural merit of the Eagle Club was divided. “The alpine hut which will house the club has the appearance of a Swiss chalet,” observed one report, while another described it as having “the severe appearance of a military blockhouse”. But with food organised from the Palace hotel, this was no perfunctory ski restaurant. Membership included strong Greek representation: Mavroleon, Goulandris and Zografos as well as the Italian nobleman and fashion king Emilio Pucci; the British financier Charles Clore; the Bolivian tin tycoon Jimmy Ortiz-Patiño; and the young Karim Aga Khan and his uncle Sadruddin.

Unlike St. Moritz, which ski snobs preferred on account of its altitude, Gstaad was within easy reach of Geneva, where many resort regulars lived and worked. For instance, Sadruddin Aga Khan found it handily located for his work at the United Nations, and became so fond of the place that he acquired the Chesery, a chic hotel, restaurant and nightclub that projected a sort of Gstaad-style jet-set gemütlichkeit. “Despite its crystal chandeliers and cowhide-lined seats,” observed one visitor, “it holds on to a chalet atmosphere”. Music, however, was far from alpine: for a time, the Chesery was famous for securing the services of the orchestra from the celebrated Elephant Blanc nightclub in Paris.

The Eagle was far from the town’s only attraction. In one year the Palace booked Maurice Chevalier to perform at a foie-gras-fuelled gala. “Chevalier sings in front of a battalion of princes and princesses,” read one headline. It proved to be such a highlight of the season that an engagement at the Gstaad Palace soon came to be seen as a significant career move for an entire generation of French singers — Edith Piaf, Juliette Greco, Johnny Hallyday, Sylvie Vartan, Jacques Dutronc, Charles Aznavour, Gilbert Bécaud and Mireille Mathieu among them. International artists performed here, too, including Louis Armstrong, Benny Goodman, Ella Fitzgerald and Dionne Warwick.

Celebrities also started to settle here, so alongside Greeks and grandees — such as the Eagle Club president, the Earl of Warwick (who lived in an Impressionist-stuff chalet with red velvet walls), and J.K. Galbraith, who used to ski with Bill Buckley and welcomed the First Widow Jackie Kennedy in 1966 — David Niven and Curd Jürgens became familiar sights around town; Yehudi Menuhin had a chalet decorated with a large violin (now there is a classical music festival bearing his name); and Julie Andrews, who settled in Gstaad with her husband-film-producer Blake Edwards, started the fashion for decorating the gables of chalets with strings of lights.

Of course, it was Edwards who propelled the resort into popular culture when he chose it as the location for his 1975 film The Return of the Pink Panther, starring another Gstaad regular, Peter Sellers, as Inspector Clouseau, the bungling detective of the Sûreté, who was sent to Gstaad in pursuit of a suave jewel thief and a world famous diamond. The film was the sixth highest grossing picture of the year in the U.S., not bad when 1975 was the year of Jaws, The Rocky Horror Picture Show, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Dog Day Afternoon, and Shampoo. The Return of the Pink Panther is a film full of immortal moments, but for devotees of seventies style, the nightclub sequence is of particular interest, with Sellers in kipper tie, Zapata moustache, and sideburns as he blunders about the groovy space-age disco. The nightclub in question was the GreenGo, located in the bowels of the Palace hotel: it is the Annabel’s of the Alps, the Studio 54 of the Saanen region, and it celebrates its half century in 2021.

The film’s world premiere took place on the terrace of the Palace — where else? In addition to Blake Edwards, Andrews and the composer Henry Mancini, le tout Gstaad was there. The official history of the hotel recounts how, “as midnight approached, woolly blankets were handed out and Julie Andrews started signing Moon River. Of course, the evening couldn’t pass without a small hiccup. When Liz Taylor, seated in the front row, suddenly and vociferously complained that the music was too loud, Henri Mancini turned to her and unmistakably hissed, ‘Shut up!’ in an ungentlemanly manner.” This must have been a novelty for Taylor, who, at that time, was the most famous woman in the world, and the owner of a chalet since the early 1960s. (Though nothing like as much of a novelty as it would have been for Gstaad had her friend Michael Jackson fulfilled his real estate dream. Jackson wanted to buy the Palace hotel from its owners, the Scherz family, who are today in their third generation at the Palace. Jackson might as well have asked to buy Buckingham Palace.)

Part of the charm of Gstaad is that it knows what makes it special and is cautious when it comes to change. For instance, when Valentino bought a chalet here he was blackballed when he applied to join the Eagle Club. But caution is balanced with pragmatism: in the end Valentino was accepted, and by the eighties he had not just joined but designed the club sweatshirt. The Italian was representative of a new crop of celebrities buying or renting chalets, Diane von Fürstenberg and David Bowie among them. And they certainly had an invigorating effect on social life: in a 1988 article in Vanity Fair, Bob Colacello described Gstaad as the sort of place where “Bowie’s houseguest Iggy Pop (né Stooge) can be found raving about Reaganomics with Pat Buckley at a Goulandris dinner”.

Gstaad in the 1980s also witnessed a crisis akin to the concern at the beginning of the century that the railway might bypass the town. Saanen airport, a relic of the second world war, had become so dilapidated that it was in danger of being closed down — fatal for those with private jets, who would then have to suffer the ignominy of being driven from Geneva airport like mere civilians. Ernst Andrea Scherz, at the Palace, realised immediately what this could do to his business, and kicked off what today would be called a crowd-funding appeal, aimed at plutocratic guests and residents. By 1986 the airport was saved, and by the second decade of the 21st century it was hosting between 7,000 and 8,000 landings and take-offs annually.

With so many private jets came a need — an absolute need — for luxury goods stores. They began to replace small businesses, butchers, bakers, grocers, and so on, a process that intensified with full pedestrianisation of the main shopping street at the end of the 1990s. At around the same time, in 1998, Gstaad acquired the sine qua non of many a top resort: its own yacht club. The minor detail that, aside from the pool that adjoined the GreenGo nightclub, Gstaad did not really boast anything in the way of a large body of water was certainly not allowed to become a barrier, but rather its raison d’être, as the club’s patron, H.M. King Constantine of Greece, explained somewhat gnomically: “Our vision is to create a unique global yacht club away from the waters, instead of another yacht club by the waters.” It seems to have worked: the club now enjoys reciprocal relations with Yacht Club de Monaco, the Yacht Club Costa Smeralda, and the Royal Thames Yacht Club, inter alia.

Gstaad has continued to evolve, and although the Palace remains in the same ownership, other landmarks have changed hands — for instance, the Olden, which opened in 1899, was bought by Bernie Ecclestone. However, the most potent symbol of Gstaad’s 21st century incarnation is the Alpina, a super-deluxe contemporary-art-bedecked nuclear-bunker-meets-grand-chalet spa hotel and apartment complex. It was so controversial that unappreciative neighbours fought, and ultimately lost, a 13-year-battle to stop the project to replace the old Alpina, which had been dynamited in 1995. It opened in 2012, 99 years after its neighbour and competitor the Palace, and in line with modern tastes it offered such up-to-date facilities as a Himalayan salt grotto. More to the taste of readers of The Rake is the cigar lounge and the annual Harry’s Bar pop-up run by Luciano Porcu himself. You could almost say that after a difficult first quarter of a century, the Alpina is becoming accepted, with one Le Rosey alumnus saying: “I think people in Gstaad are happy to have the facilities of the Alpina.” Cigars and Harry’s Bar… what’s not to like?

One of the most noticeable features of the Alpina is the art. The permanent collection includes works by artists such as Tracey Emin and well-connected pun-maker Massimo Agostinelli. The Impressionists that used to adorn the walls of plutocratic chalets are out of place in the Peter Marino-inspired décor favoured by the newly rich, and the world’s leading art dealers have made it their business to make sure that Gstaad has access to the sort of wealth-appropriate, blue-chip, contemporary wall-power that has become one of the must-haves of the crazy rich classes. Larry Gagosian has been spotted around the resort, and in 2015 Hauser & Wirth staged a by-appointment exhibition in the chalet where Gunter Sachs lived (and where he killed himself in 2011). This was followed by a remarkable outdoor exhibition of large-scale works by Calder during 2016.

It is interesting to note that the exhibition took place between July and September, and that one of the sculptures was located at that late-19th century beauty spot of Lauenensee. In fact, it is enough to make you think that someone at Hauser & Wirth had been reading their 1895 Baedeker.

This article orginally appeared in Issue 67 of The Rake.