British War Poets: By the Pen and the Sword

With the October issue of The Rake celebrating British military heroes now on the stands, we raise a sombre toast to the literary heroes produced by the horrors of World War I.

“The truly creative mind,” Pulitzer and Nobel Prize winning American novelist Pearl S. Buck once wrote, “is no more than this: a human creature born abnormally, inhumanly sensitive.” If we take ‘sensitivity’ here to mean emotional responsiveness to external stimuli, what happens when a vast cross-section of personality types are plunged into conditions that are intensely traumatic?

Perhaps the best answer we have comes in the form of the terror-soaked stanzas of the English war poets. World War I is a conflict more inextricably linked to gritty literary endeavour than any other, and it’s tempting to put this down to the realism and naturalism movement that portrayed a grainier, more visceral treatment of such horrors, that were de rigueur late in the previous century. The creative journey of one of the most publicly outspoken war poets, though, suggests otherwise.

When War broke out, Siegfried Sassoon was spending some idle years playing cricket and golf, foxhunting, writing poetry and coming to terms with his then-illegal homosexuality. Seduced by the patriotic fervour gripping British society in 1914, he enlisted first as a trooper in the Sussex Yeomanry, then with the Royal Welch Fusiliers. Sassoon’s relocation to the Western Front saw him exposed to the horrors of trench warfare – a far cry from the Victorian yarns featuring dashing heroes in gleaming uniforms with which he’d grown up in a Kent backwater. His penchant for literary romanticism held out for a while: reviewing the poetry his friend Robert Graves was preparing for publication, Sassoon – an ardent admirer of the flowery syntax and imagery of the romantic poets, along with the king-and-country positivism of Rupert Brooke’s sonnets – found Graves’s work indulgently, unpalatably gritty.

But the deaths of his younger brother Hamo at Gallipoli in 1916 and close friend David Thomas re-smelted both his artistic inclinations and his attitude to armed conflict. Meetings with prominent pacifists including Bertrand Russell ensued, and by the time his first collection of war poems, The Old Huntsman, was published in May 1917 Sassoon’s verse was soaked with caustic contempt for authority and unquenchable patriotism.

Witnessing first-hand the Battle of the Somme, the first day of which he later described as a “sunlit picture of hell”, then the Battle of Arras in April 1917, cemented the pacifist leanings so eloquently set out in a letter to The Times, written during a convalescence spell back in England while he was suffering from a shoulder wound and acute “survivor’s guilt”. It was in a shell-shock hospital, Craiglockhart – he was likely sent there to be silenced - that he met a poet whose critical and public reputation would go on to exceed Sassoon’s, and all on the strength of a body of work created almost entirely over 14 months.

Wilfred Owen was working as a private tutor and immersing himself in the mercurial stanzas of Keats and Shelley near the French Pyrenees when, on a street corner 1,200 miles away in Sarajevo, a pistol bullet killed Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria and his wife. Commissioned as a second lieutenant, he suffered a series of traumas – suffering concussion after falling into a shell hole on one occasion; being in exploding range of a trench mortar on another, as well as spending several days lying unconscious on an embankment amongst the remains of a fellow officer – before ending up at Craiglockhart, where Sassoon, along with Graves and H.G. Wells, would act as literary mentors.

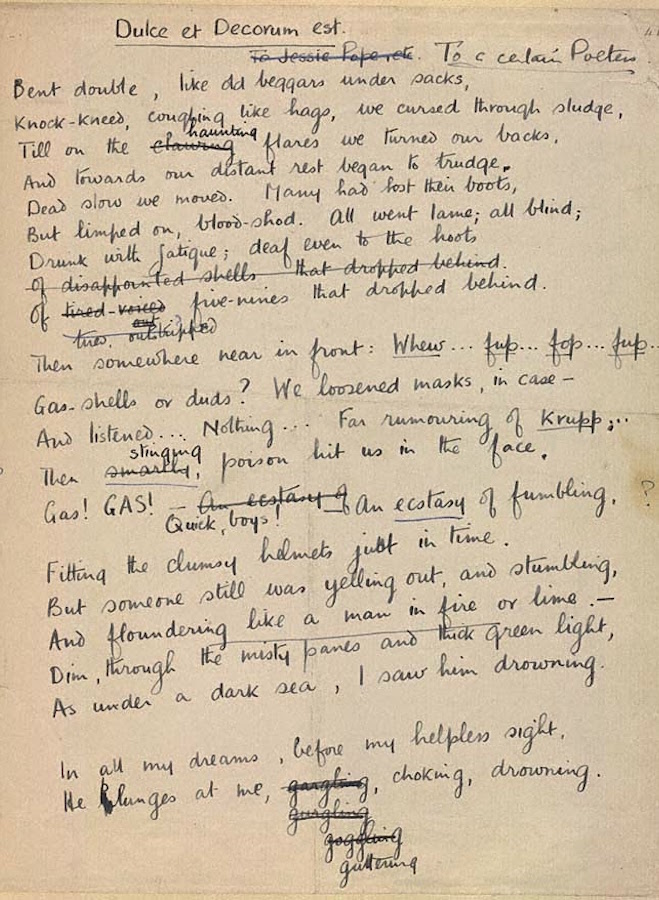

It’s impossible to overstate Owen’s legacy: the bleak realism, raw indignation, authentic compassion and technical skill conspired to ensure that his poems, and especially certain lines from within them (“Gas! Gas! Gas! Quick, boys! - An ecstasy of fumbling”; “Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time”), since his death, have contributed more to our understanding of the events of 1914-1918 than all of Hollywood’s output on the subject put together.

It would be wrong to think of the war poets as tortured naval gazers whose pistols were only ever fired upwards into the Flanders mists. The despair, the borderline nihilism, in which Sassoon became immersed prompted him to take gallantry into the parlous fringes of invincibility, and he became notorious for near-suicidal front-line exploits that earned him the sobriquet ‘Mad Jack’ and saw him decorated twice. Owen was posthumously awarded a Military Cross in recognition of his courage and leadership (he was killed on 4 November 1918 during the battle to cross the Sambre-Oise canal at Ors, placing him alongside Edward Thomas, Isaac Rosenberg and Charles Sorley in the annals of World War I lyricists who didn’t make it home).

And, not all the war poets saw battle as apocalyptic insanity. Julian Grenfell’s ‘Into Battle’, published just after mortal wounds got the better of him in 1915, ends with the lines: “And find, when fighting shall be done; Great rest and fullness after death.” What unites them all, though, is their stirring ability to fulfil Wordsworth’s description of poetry as “the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings”.

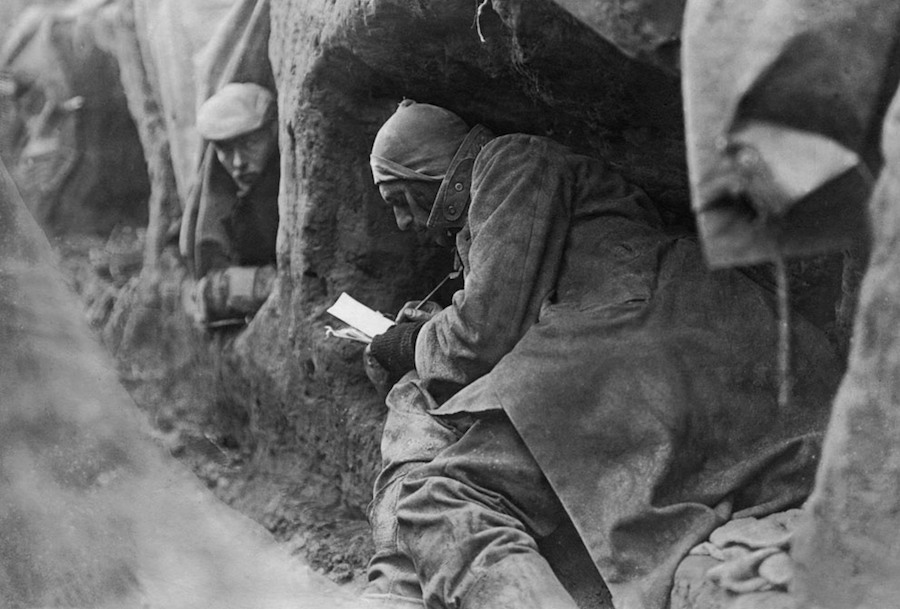

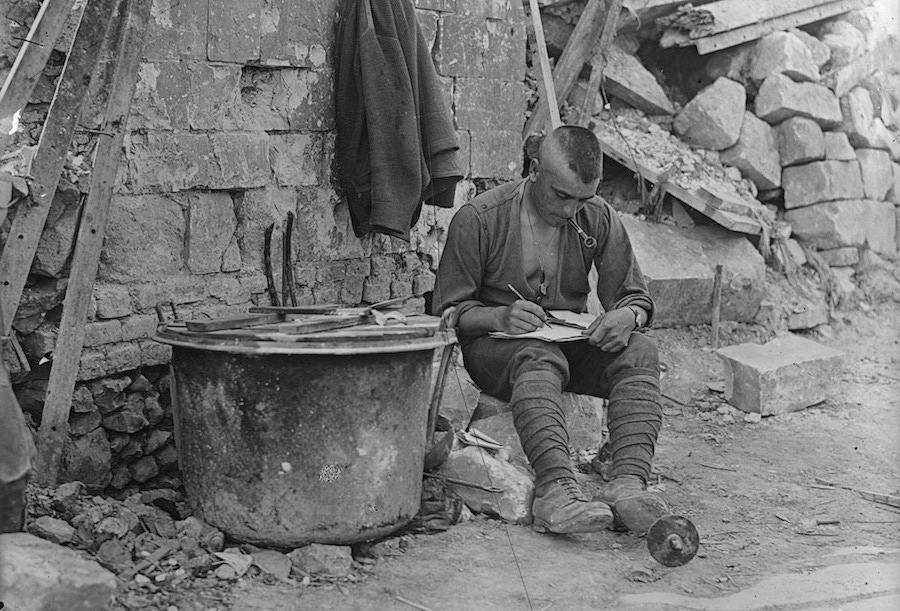

Amongst the rubble and wreckage of war, a pipe smoking soldier perches on a rock with his pen and paper.

Amongst the rubble and wreckage of war, a pipe smoking soldier perches on a rock with his pen and paper.

Amongst the rubble and wreckage of war, a pipe smoking soldier perches on a rock with his pen and paper.

Amongst the rubble and wreckage of war, a pipe smoking soldier perches on a rock with his pen and paper.