David Bailey & Jean Shrimpton: Breaking the Class Ceiling

This iconic swinging London couple embodied the ’60s shift of British culture from the upper class to the masses.

Aside from the advent of the birth-control pill, unleashing a wave of sexual permissiveness, perhaps the greatest change to occur in Britain during the 1960s was the posh, aristocratic establishment losing its place at the cultural vanguard — surrendering the zeitgeist to the aitch-droppin’ everyman.

Suddenly, after centuries of dominance, the toffs were no longer on top. ‘Sarf’ London lads Michael Caine and Terence Stamp succeeded the tony David Niven and Laurence Olivier to become the biggest movie stars of the day. London swung to the sounds of suburban Liverpudlians The Beatles, and middle-class Kent boys, Mick and Keef. Their Dartford neighbour Peter Blake and the son of “radical working-class” parents, David Hockney, ruled the art world. Meanwhile, arguably the most important British political figure of the decade turned out to be a proletarian topless showgirl, Christine Keeler, whose scandalous affairs brought down Harold Macmillan’s Conservative government and ushered the party of the working class, Labour, into power.

The times they were a-changin’.

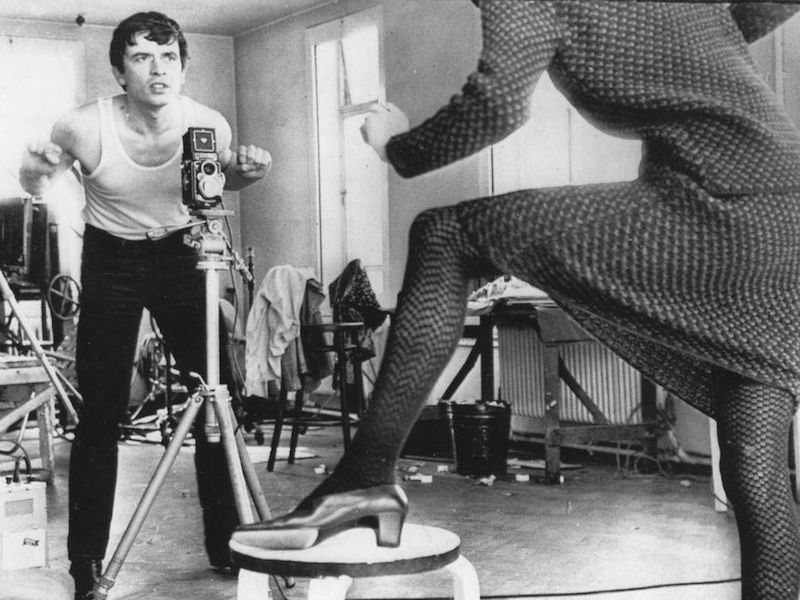

Replacing the upper-class likes of Hampstead-bred Cecil Beaton came a fresh crop of cocky cockney photographers, documenting London’s newly egalitarian society. The leading names were a trio dubbed “the Black Trinity” by usurped society photographer Norman Parkinson: Brian Duffy, Terence Donovan, and David Bailey.

Bailey’s father was an East End tailor and nightclub operator, who’d been given a nasty scar (the mouth-to-ear wound requiring 68 stitches) by the infamous Kray brothers. The young, dyslexic Bailey quit school at 15, utterly illiterate, and only learnt to read when he enrolled for national service with the Royal Air Force in 1956. It was during his time with the RAF, including a stint stationed in Singapore, that Bailey first took up the camera. After demobbing in 1958, Bailey won apprenticeships with prominent photographers David Ollins and John French. By the end of 1960, the handsome young scamp had finessed his way into a job with British Vogue.

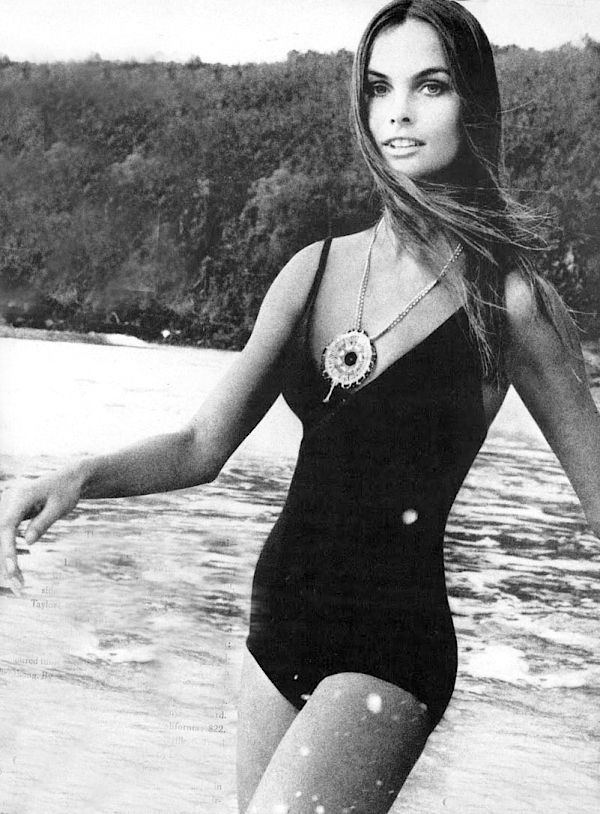

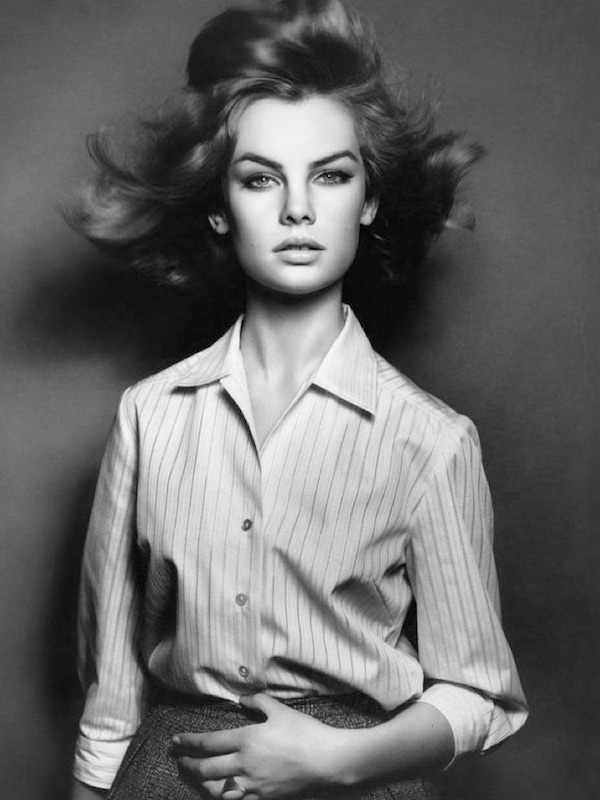

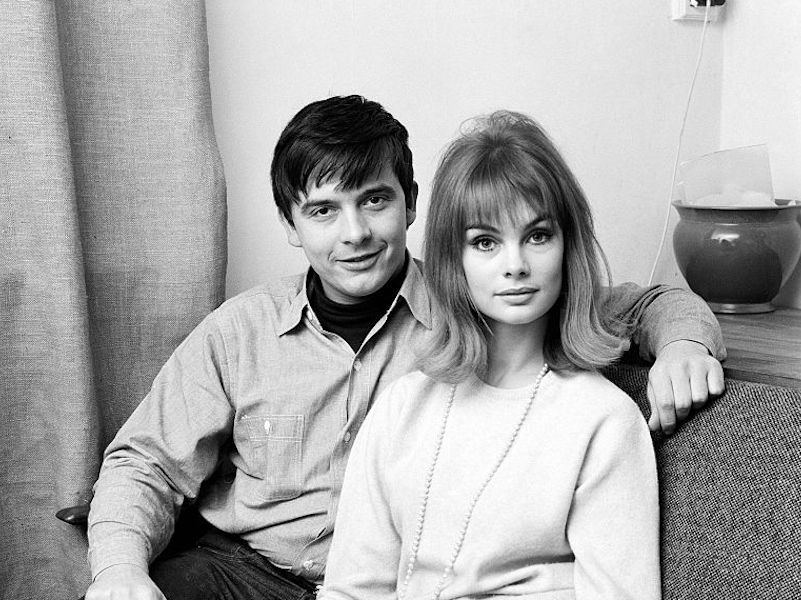

A number of his earliest editorials for the magazine featured a young model Bailey had spotted when she was shooting a cereal advertisement with Brian Duffy. The powers that be at Vogue (whose to-the-manor-born fashion editor, Lady Clare Rendlesham, favoured aristocratic models doing sophisticated things in elegant settings) resisted Bailey’s casting of fresh-faced farmer’s daughter Jean Shrimpton, but the photographer insisted — and prevailed. Bailey and Shrimpton’s gritty, witty collaborations reshaped Vogue’s aesthetic and made them both stars. “I think we created each other,” Bailey told an interviewer several years ago. “You can’t create a portrait by yourself. I always tell people it’s them taking the photograph, not me. For me it’s always about the people.” Of Shrimpton, Bailey remarked, “She was magic. In a way she was the cheapest model in the world — you only needed to shoot half a roll of film and you had it.” (In fact, during her peak, Shrimpton would become the highest-paid model on Earth.)

The duo’s mutual appreciation extended beyond the professional, with the 22-year-old Bailey abandoning his wife for the 17-year-old waif not long after they’d met. “We were instantly attracted… and whenever we worked together this attraction created a strong sexual atmosphere,” Shrimpton wrote in her biography. “My meeting with Bailey was a fateful one, for I owe everything that I have since become as a model and as a woman to him,” she said in 1964. “He taught me that I must have a mind as well as a body.”

Shrimpton once explained that she was far from the only one to be instantly seduced by Bailey’s likely lad allure and cheeky chappy charms. “Women love him,” she said. “Gays adore him. Children and animals run to him. Mothers dote on him. He is universally attractive, except to fathers.” (On Bailey’s first visit to Shrimpton’s family farm, her dad made his feelings for the photographer quite plain. “I had to hide in the hay loft, over the pigs, because he came after me with a shotgun,” Bailey recounted of the meeting.)

Bailey, who by one pundit’s estimate bedded almost 400 women, took full advantage of the sense of sexual liberation in the air in the 1960s. A lascivious kid in a candy store, he simply loved the ladies. All of ’em. “They are all so beautiful. They are all so lovely. There is absolutely nothing in them that I dislike. I love them. Every one of them is a mystery,” he said in a late-’60s interview. The promiscuous lead character in Antonioni’s Blow-Up, based in large part on Bailey, wasn’t far from the mark — nor was the shag-happy Austin Powers, another partial Bailey homage. Within a few years, Shrimpton had tired of the philandering photographer’s womanising and left him, taking up with Terence Stamp. “I had three or four other girls on the go,” Bailey said of the break-up. “I couldn’t complain.”

Newly single, in 1965, he met and married the actress Catherine Deneuve. That union came to an end in 1972 when another 17-year-old, model Penelope Tree, caught Bailey’s eye. He kept on mixing business with pleasure, marrying model Marie Helvin in 1974, divorcing in 1982, and wedding model Catherine Dyer, two decades his junior, in 1986. They’re still together, and the 79-year-old Bailey remains a sought-after snapper. Shrimpton long ago retired to raise a family with her husband, photographer Michael Cox, and run a small hotel in Penzance, Cornwall.

The duo’s photographic legacy is enormous. But we’ve more to thank them for than that. Contemporary Britain owes a debt to Bailey, Shrimpton and their swinging compatriots for rattling the establishment and smashing the ‘class ceiling’ — proving that the cultural landscape can be shaped by individuals raised on estates of the downtown, council kind, just as easily as those bred on the Downton, ancestral sort.