Full Marquis: Alfonso de Portago

To say he lived his life to the fullest would be a gross understatement; the life of Alfonso de Portago was bursting at the seams right 'til the very end.

The third musketeer in our November series on excess was a Spanish jockey, bobsledder, flier, polo player, jai-alai expert and racing driver, a handsome twentieth-century nobleman-conquistador who tackled the Grand National, Formula One and the Winter Olympics. His full name was Alfonso Antonio Vicente Eduardo Angel Blas Francisco de Borja Cabeza de Vaca y Leighton: for short, the Marquis de Portago. He was both the sort of man a middle-aged post-war Don Quixote would love to be and a kind of Quixote himself, a precocious version of his near-namesake Alonso Quixano transformed and killed decades too early by the boundlessness of his own fantasies.

Portago’s pedigree threaded blue blood with nerves of steel. His grandfather was governor of Madrid; his father was Spain’s best golfer and an audacious gambler who once won $2 million at Monte Carlo; Alfonso XIII, the previous king of Spain, was his godfather. Reading through his exploits, he sounds like the sort of man who could, infuriatingly, turn his hand to anything. At 17, he won a $500 bet by flying a plane under London Bridge. He twice entered the Grand National as a “gentleman rider”. In 1956, he enlisted his cousins to help represent Spain in their first ever bobsleigh team at the Winter Olympics, where they came an impressive fourth (I smell a Cool Runnings prequel). Gregor Grant, founder of Autosport Magazine, reckoned he could be “the best bridge player in the world if he cared to try, he could certainly be a great soldier, and I suspect he could be a fine writer.”

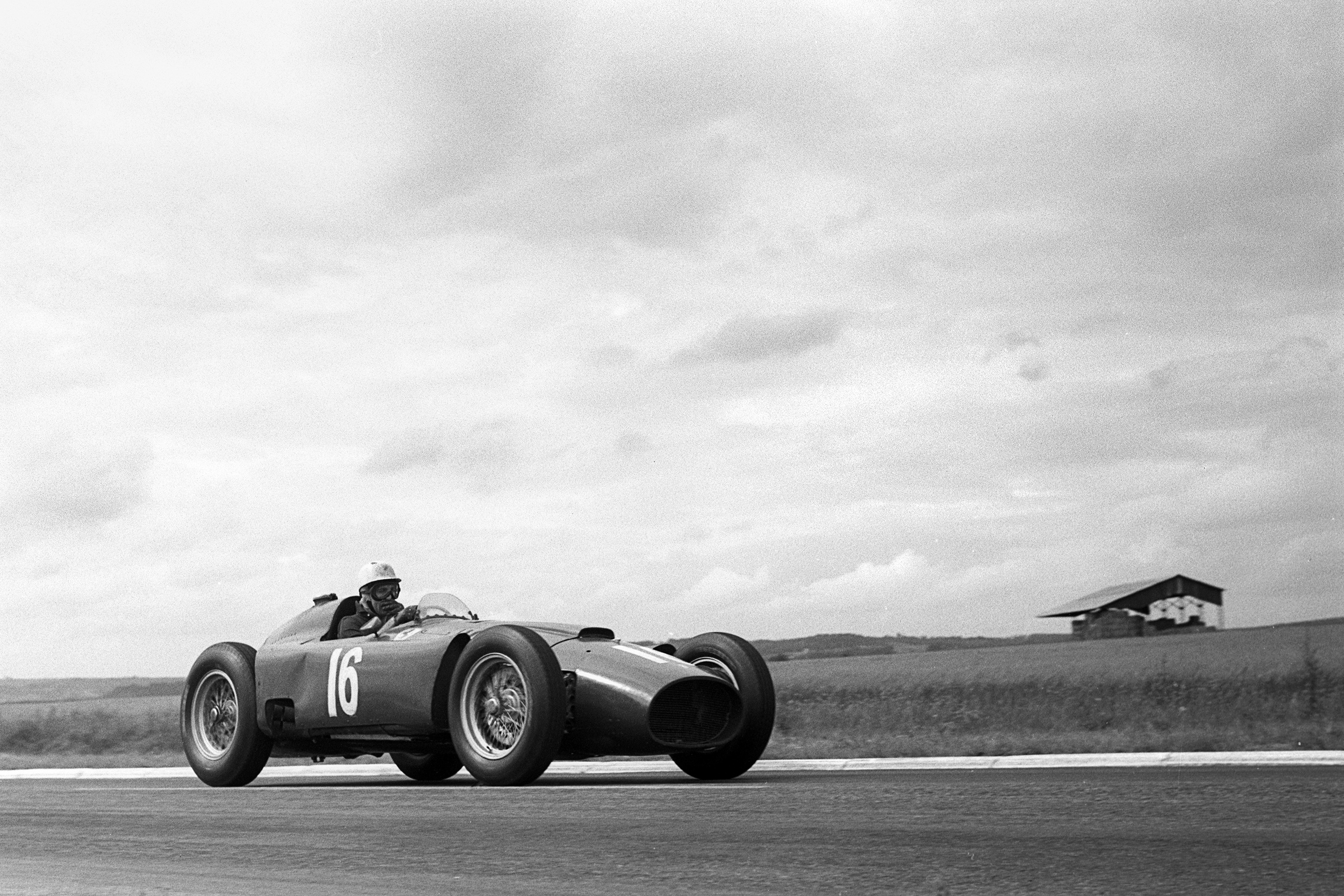

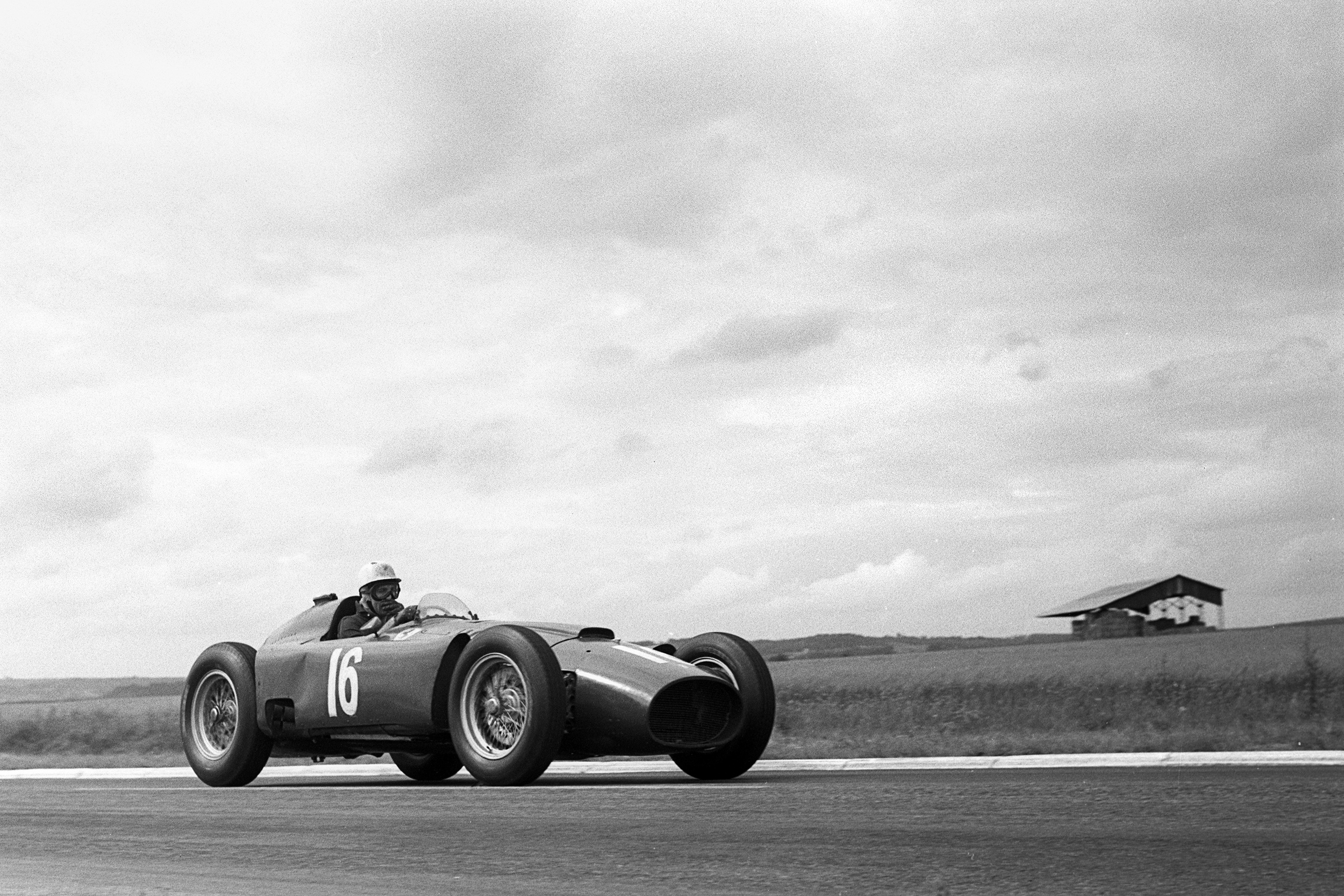

Alfonso found his ultimate calling as a racing driver. Signed up by Ferrari after an encounter with Luigi Chinetti (the company’s US importer), he co-drove in the 1953 Carrera Panamericana, then raced independently later that year at the 1000km Buenos Aires in a personal Ferrari Sport. He soon notched up six major first-places, including the Tour de France automobile race, the Oporto Grand Prix and the Nassau Governor's Cup, twice. His high-risk, abrasive driving style took such a toll on brakes, clutches and transmissions that he often needed several cars to finish a race. With Formula One the inevitable next arena, he took place in five Grand Prix and came second at Silverstone in 1956. At the same track a year earlier, he lost control of his car when he hit a patch of oil at 140mph. He was thrown out of his car and could easily have been killed, but escaped with a broken leg. He ignored the omen.

He was the sort of man a middle-aged post-war Don Quixote would love to be.

Unsurprisingly, he was a precocious philanderer as popular with women as he was unpopular with his fellow drivers, who saw him as arrogant. At just 20 he married Carroll McDaniel, a former model he barely knew who was several years older than him. Though they had two children together, he soon tried to divorce her so he could legitimise a Mexican marriage certificate to Dorian Leigh, a fashion model eleven years his senior. There was also a third lover, the last woman he’d ever kiss. According to Car and Driver, at the Rome checkpoint of his last race, he stood on the brakes, locked everything up, waited for her, kissed her and held her in his arms until an official furiously waved him on. The woman in question was Mexican actress Linda Christian, ex-wife of actor Tyrone Power who had switched from the man who played Zorro on-screen to his real-life incarnation.

And so to 12th May 1957, that fateful day in the Mille Miglia, an Italian open-road endurance race over a thousand miles. An uncharacteristically nervous Portago worried it was too dangerous to run such a long course when it was almost impossible to know every corner, even with a navigator, but he went ahead with co-driver Edmund Nelson. In third place, Portago was travelling at 150mph on a straight-road in Lombardy between Cerlongo and Guidizzolo when a tyre exploded on his Ferrari 335 S. The car cannoned over a canal, ricocheted back and killed nine spectators, his co-driver Nelson and Portago himself. A concrete milestone was gouged from the ground by the car and thrown into the crowd, killing two children. Portago’s own body was found beneath his Ferrari in two separate sections.

What a sad, violent end to a giddy existence. Like James Dean, Portago died in a car crash in his twenties in the 1950s; like Dean, he resisted the warning signs (Alec Guinness had told Dean a week before his death that he’d die if he kept driving that Porsche Spyder), a different map in mind for his own legend: “I won’t die of an accident. I’ll die of old age or be executed in some gross miscarriage of justice.” Cervantes deserves the last word on this strange knight and a single line won’t do: it’s important to measure the marquis’ half-mad ambition (“In order to attain the impossible, one must attempt the absurd”) against that destructive selfishness (“Jests that give pains are no jests”). But his most important characteristic was his vitality: “until death, it is all life.” For twenty-eight years, if nothing else, Alfonso de Portago was all life.