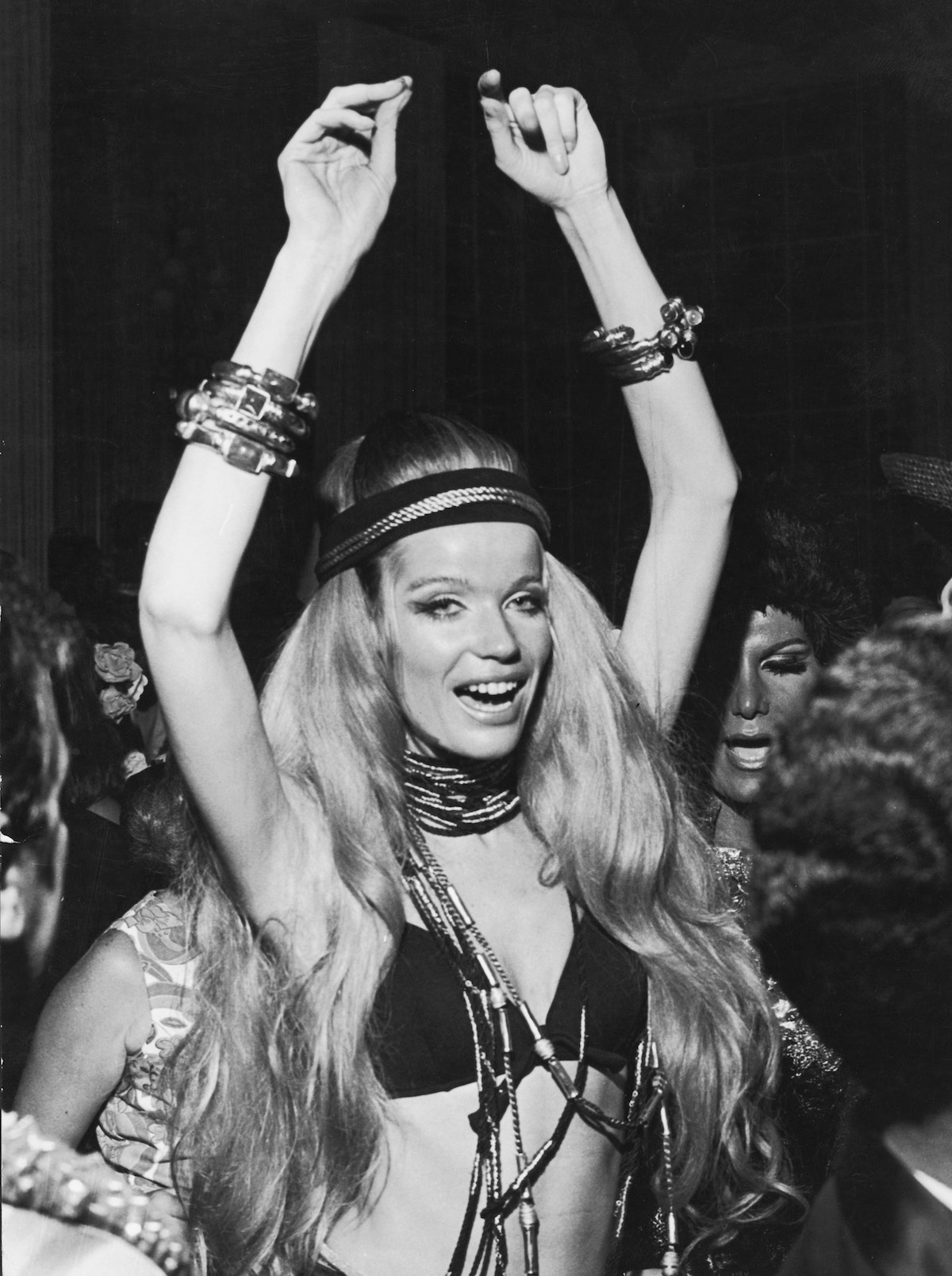

Raising The Teutonic: Veruschka von Lehndorff

She is the daughter of a doomed German resistance fighter who used modelling as an escape from the pain of her childhood. ‘I am Veruschka’, she would say, ‘and I’d like to see what you can do with my face.’ Well, if you insist ...

Back in the day, you knew you’d made it when the world knew you by only one name: Twiggy, Prince, Cher, Liberace. Today, the effect is somewhat diluted by a few worthy candidates — Beck, Drake, Madonna — and a seemingly endless array of the undeserving (Miley, Enya, Fabio). Proto-supermodel Veruschka belongs in the former category. Before the name was co-opted by every drag queen who couldn’t think of a decent pun (Crystal Decanter, Stella Trajectory, Gale Force; c’mon, ladies, it’s not that, ahem, hard), Veruschka could be only one person.

Veruschka’s story is all the more intriguing because it came close to not happening. Now 77 years old, she was born in 1939 as either Vera Grafin von Lehndorff-Steinfort or Veruschka von Lehndorff (you know how vague Prussian nobility can be when it comes to names). Burdened by the inconvenience of a conscience, her father, Count Heinrich von Lehndorff, joined the German resistance after reportedly witnessing the execution of Jewish children. His involvement in what became known as the 20th July plot to assassinate Hitler in his East Prussia field headquarters — which also happened to be the von Lehndorff family home — led to his execution.

Veruschka, her mother and her three siblings were interred in a camp for the children of resistance fighters, where they survived the war but lost everything else. Like many post-war refugees, they drifted around Europe in search of hope and opportunity, eventually settling in Florence, where the young Veruschka harboured modest dreams of becoming an artist. She got it half-right, in that she would play an integral role in creating some of the most iconic images of her day, albeit infront of the lens.

At 6’3” she was hard to miss, and atop the seemingly endless limbs and torso, more willowy than a summer river bank, was a face that could vacillate between little girl lost and imperious Romanov princess. Her backstory is quite the departure from the clichéd, ‘Yeah, I was a bit of a tomboy, and then, one day at the mall, a lady at Starbucks asked if I’d like to be a model, which was weird because I just like skateboarding’.

Although she would eventually command the then gobsmacking fee of $10,000 per shoot, not everyone wanted to get on board the ‘V’ train to begin with. “I had a hard time,” she has said. “I was too tall, too baby-faced, and they just didn’t think it worked together.” It was only when she teamed up with photographer Johnny Moncada in 1964 that this curious amalgam found its rhythm — which turned out to sit halfway between a dirge and torch song, as almost every Veruschka image was underpinned by a note of melancholy. “I saw modelling as a way of getting out of my dreary life,” she said of the years after her father’s execution and nomadic existence. “It was a fantasy that had nothing to do with the reality I had dealt with. Even though I was happier, I still couldn’t let that pain go.” No less an authority than Richard Avedon called her “the most beautiful girl in the world”, and Diana Vreeland put her on the cover of Vogue 11 times. In one memorable 1967 shoot, Veruschka was teamed with a cheetah, and managed to out-feline the cat. It was the same year in which she appeared on the cover of Life magazine with the headline, The Girl Everybody Stares At.

Film, inevitably, came calling, and despite her finely calibrated opening line in Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1966 offering Blow-up — “Here I am” — she had well and truly arrived a while beforehand. She was on screen for only five minutes, but the scene in which the barely clad Veruschka is straddled by a feverishly snapping photographer (based on David Bailey) was once voted by Premiere magazine as the sexiest in film history. Along the way she was pursued by the likes of Dustin Hoffman, Al Pacino, Jack Nicholson and Warren Beatty. She was art-directed by Dalí, and even scored a brief appearance in the James Bond reboot Casino Royale.

After numerous initial knockbacks, the survival instincts kicked in. Meek Vera wouldn’t cut it in the competitive world of New York modelling. She needed to create a persona that was nine parts irresistible to one part fuck-off scary. Veruschka was this creation. At auditions — where she was the one looking for work — her standard opening line to photographers was, “I am Veruschka who comes from the border between Russia, Germany and Poland. I’d like to see what you can do with my face.” This is equivalent to showing up for your first day at KFC and telling Colonel Sanders you think you could improve on his 11 secret herbs and spices.

This braggadocio was matched by career-lengthening creativity that at times could border on gently satirising the very industry that had made her a global woman of desire. “After I had been modelling for a year or two, I realised it could bore me to death, but these characters I wanted to play were always in my head, so I started to express them in a different way,” she said. “I had already invented Veruschka, and she becamefamous.” She was no prude, either, and if she believed the shot warranted it, could slip out of her gear quicker than you could say, Gott im Himmel! So impactful were the images that even in 1992 — decades after her heyday — British indie darlings Suede used a shot of Veruschka wearing nothing but a man’s suit in bodypaint as the cover for their single The Drowners. It’s no understatement that she was a pioneer in daubing the body. As early as 1965 she began experimenting with this art form, transforming herself into wild animals, film stars, dandies and, in a neat comment on the notion of objectification, dirty, leering old men. For that — and for much more, Veruschka — we say a hearty danke schön.