Style Heroes: David Niven

The template for 007 and the original Riviera-dwelling ‘dirty rotten scoundrel’, David Niven made a career portraying the quintessential British gentleman.

Forget former milkman Sean Connery. It was David Niven that Ian Fleming had in his mind’s eye when creating the character of James Bond. Bond’s resemblance to the actor even serves as a plot point in Fleming’s novel, You Only Live Twice. But it wasn’t merely angular good looks the two shared. A distinguished soldier and hard-drinking lothario whose list of conquests included many of the midcentury’s most beautiful women, Niven resembled 007 on numerous levels.

James David Graham Niven was born in March 1910 in London, his father a British officer who was killed in the First World War just five years later, leaving the family to inherit little but a string of debts. His mother, a Frenchwoman, soon remarried Conservative party grandee Sir Thomas Comyn-Platt. Biographers have suggested that Comyn-Platt was in fact Niven’s biological father — he and Niven’s mother had been involved in a long-term affair. True or not, the man Niven called ‘Uncle Tommy’ neither acknowledged paternity nor embraced parenthood, convincingly playing the part of a cold and distant step-father.

Conditions at home led to Niven rebelling as a youth; he described himself as a “thoroughly poisonous little boy” who may easily have fallen into a life of crime. In an attempt to curb his wicked ways, Niven’s parents packed him off to a succession of boarding schools. Here, “there was a great deal of bullying” and Niven was constantly “bashed around”, he said, making his first forays onto the stage in an attempt to be better liked.

After moving to the liberal-minded Stowe school, Niven began his prolific lifelong pursuit of carnal pleasures, embarking upon an affair with a London prostitute. “I was a 14-year-old heterosexual schoolboy,” he recalled. “Nessie, when I first saw her, was 17 years old, honey-blonde, pretty rather than beautiful, the owner of a voluptuous but somehow innocent body and a pair of legs that went on forever. She was a Piccadilly whore.”

Educated by Nessie in the act of love, Niven went on to the Royal Military College at Sandhurst to study the art of war. He subsequently joined the British Army and was commissioned as a second lieutenant. Niven was devastated when he failed to pass muster for the prestigious, kilt-clad Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, and was instead compelled to serve with the Highland Light Infantry, who wore far less distinguished tartan trews.

Quitting the army, in the early 1930s Niven made his way to America and began to win bit parts in various films. A minor role in MGM’s Mutiny on the Bounty brought the actor to the attention of legendary studio boss Samuel Goldwyn, who signed him to a $100-a-week contract with MGM. He quickly achieved authentic star status, appearing in films such as The Charge of the Light Brigade with his pal Erroll Flynn, Bachelor Mother with Ginger Rogers, Raffles with Olivia de Havilland, and Wuthering Heights with Laurence Olivier and Merle Oberon, Niven’s live-in lover — though one whom, like most of his romantic partners, he was quite incapable of remaining faithful to.

After he and Oberon broke up, Niven famously shared a Malibu beach house dubbed ‘Cirrhosis by the Sea’ with Flynn. Here, the two would host parties for Hollywood pals including Humphrey Bogart, Douglas Fairbanks Jr. and Fred Astaire, consume copious amounts of alcohol (hence the bungalow’s liver-withering moniker), and share around girlfriends, liquor and illicit substances with equal ease.

The party came to a temporary end with the Nazi invasion of Poland in 1939. Though there was little chance he would’ve been conscripted, when World War II broke out, Niven immediately returned home to England and rejoined the army. In putting a pause on the self-centred, sybaritic behavior, “I was saved from being a total shit by the war,” Niven said. He initially served with the Rifle Brigade in France, before joining the ‘Phantom’ special reconnaissance GHQ Liaison Regiment, taking part in the formation of the Commandos, and participating in the landings at Normandy.

Niven had a number of encounters with Winston Churchill during the war, the British prime minister telling him, “Young man, you did a fine thing to give up your film career to fight for your country. Mark you, had you not done so, it would have been despicable”. His service was clearly distinguished, as Niven rose throughout the course of the conflict from captain to the rank of lieutenant colonel.

In later life, he spoke very little of his wartime experiences (except to joke, “Going to war was the only unselfish thing I have ever done for humanity”). During hostilities he was less hesitant — when asked by a battlefield correspondent how life on the front lines was treating him, Niven quipped, “Well on the whole, I would rather be tickling Ginger Rogers’ tits.” After the Allies’ victory, he returned to Hollywood to do just that — or at least, to resume his acting career.

His first years back in the US were marked by misfortune. In 1946, Niven’s wife Primula ‘Primmie’ Rollo, mother to their two young sons, died in a freak hide-and-seek accident during a party at actor Tyrone Power’s house. The loss left Niven suicidal. He floundered in his career, acting in a series of flops in the late ’40s, before regaining his stride in the ’50s with box-office successes including Otto Preminger’s controversial The Moon is Blue (1953) and Bonjour Tristesse (1958), the 1956 smash Around the World in 80 Days, and 1958 drama Separate Tables, for which Niven won the Best Actor Oscar. Notable sixties outings included Pink Panther (1964) and James Bond spoof Casino Royale (1967), where Niven finally had the chance to fulfill Fleming’s wish that he portray 007.

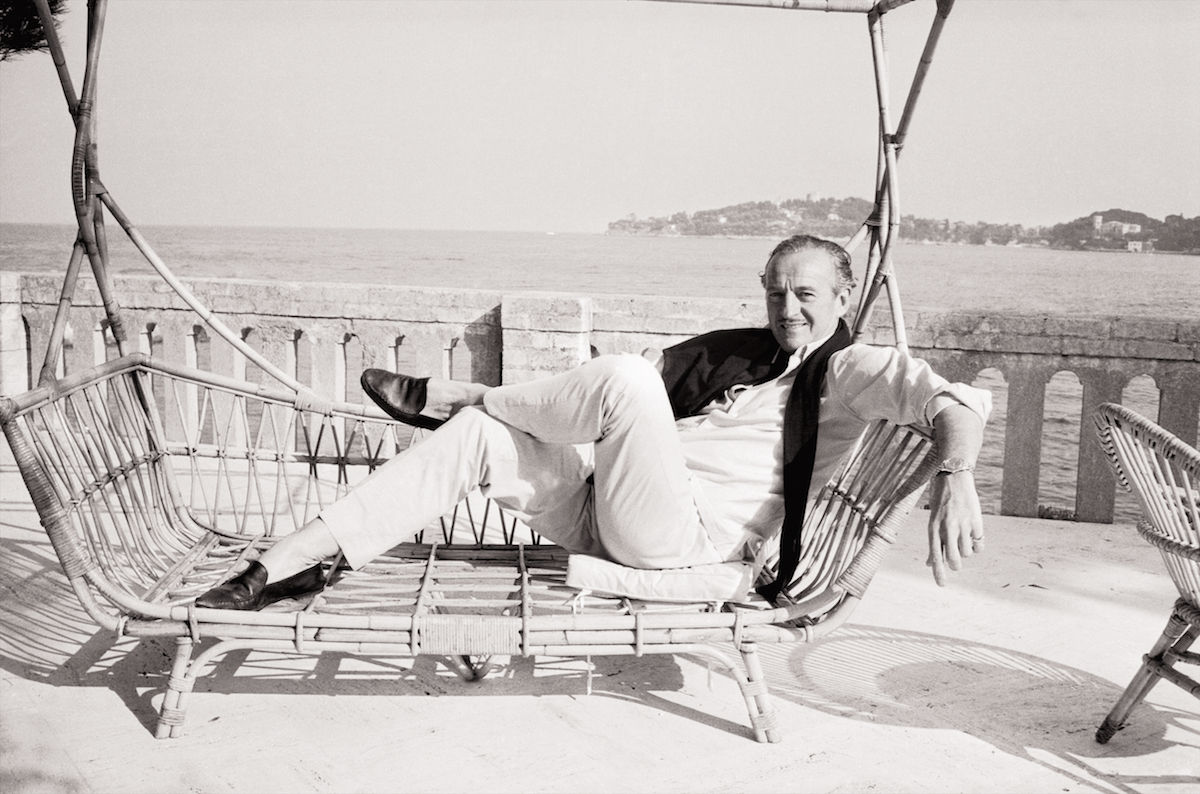

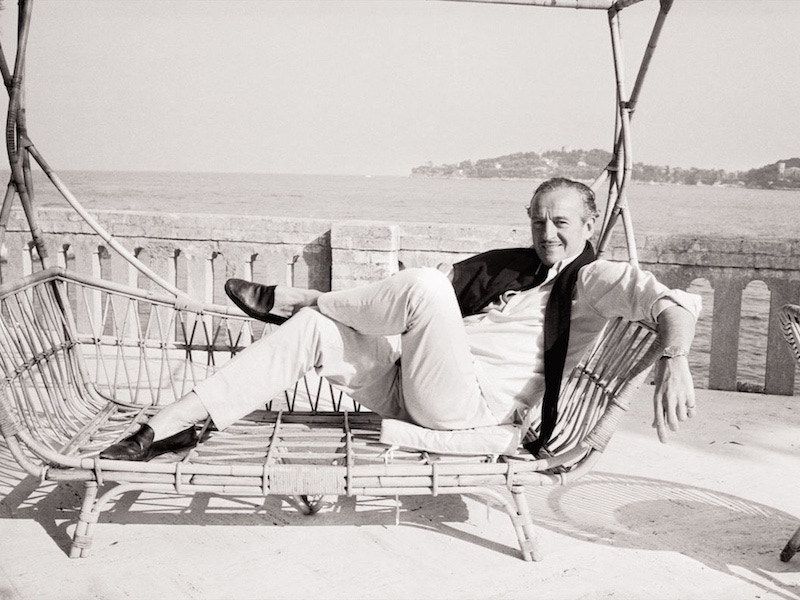

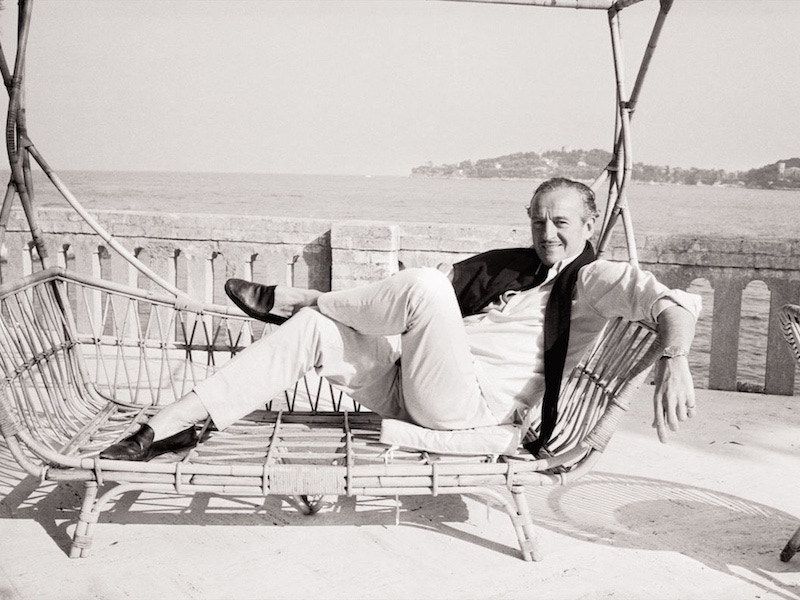

With his light trousers, white shirt, loafers without socks and jumper carelessly thrown over the shoulders, David Niven effortlessly embodies the Riviera lifestyle here, circa 1960s.

With his light trousers, white shirt, loafers without socks and jumper carelessly thrown over the shoulders, David Niven effortlessly embodies the Riviera lifestyle here, circa 1960s.

With his light trousers, white shirt, loafers without socks and jumper carelessly thrown over the shoulders, David Niven effortlessly embodies the Riviera lifestyle here, circa 1960s.

With his light trousers, white shirt, loafers without socks and jumper carelessly thrown over the shoulders, David Niven effortlessly embodies the Riviera lifestyle here, circa 1960s.

Branching out from acting, he cofounded a television content studio, Four Star Productions, which enjoyed enormous success throughout the 1950s and ’60s. Niven also began writing books, his 1971 autobiography The Moon’s A Balloon selling more than five million copies. His income was such that Niven was forced to become a tax exile and take up residence in Switzerland, at Château-d’Œx near Gstaad. He bought a summer home on Cap Ferrat, a 19th century villa with views of Beaulieu-sur-Mer, the tony seaside town that served as inspiration for Beaumont-sur-Mer — the setting for Niven and Marlon Brando’s 1964 film Bedtime Story (and its 1980s remake, Dirty Rotten Scoundrels). Niven himself could tell ‘bedtime stories’ of beauties including Rita Hayworth, Marilyn Monroe, Loretta Young, Grace Kelly and a host of less well-known conquests. He told a biographer he’d been addicted to sex since his teens. “I had some bizarre illness. I had to have sex,” he said. “I paid for it when I had to. Often I didn’t because there were plenty of starlets willing to sleep with anyone they thought might be able to help them in their careers.” Proving that karma can indeed be a bitch, the prolific player got his comeuppance in the form of second wife Hjördis Tersmeden, a Swedish former model who made Niven’s life a misery and was despised by his friends. They nevertheless remained married for the sake of the two daughters they’d adopted together, Hjördis lingering until the bitter end — for better or worse (though mostly the latter, by all reports). In 1983, when Niven was dying of motor neurone disease, which rendered him nearly speechless, his wife would taunt him over the fact that he had lost his abilities as a raconteur. “Look at him,” she’d cruelly remark to visitors. “He can’t tell any of his stories now.” In Niven’s final weeks, Hjördis left him in the care of a nurse at their Swiss home, while she stayed in Cap Ferrat. “Hjördis had pretty much given up,” said Niven’s son, David Jr. “She was not Sweden's answer to Florence Nightingale by any stretch of the imagination.” Niven hardly needed bringing down a peg. At the root of the self-deprecating humour that made him a favourite on the talk-show circuit was a deep-seated insecurity. He once told actor John Hurt, “I know exactly what my position is, old cock: I’m a second-rate star.” Cary Grant, however, considered Niven a true rarity in Hollywood. “He was a funny man and a brave man, a good man,” Grant recalled of his flawed friend. “And there were never too many of those around here.”