In From the Cold: Canada Goose

Explorers and emergency crews have long relied on the quality outerwear provided by Canada Goose. Now, having just celebrated their 60th birthday, the extreme-weather specialists are extremely cool.

In the universe that occupies the collective mind of The Rake, every waking day presents an opportunity to showcase one’s latest fashions, and to display to the outside world what a cultivated individual one is — it’s one of many reasons why wearing nice clothes is such a pleasurable experience. What we wear helps others form first impressions, and allows us to present an image of ourselves we want the rest of the world to see. There are some instances, though, when adhering to a particular aesthetic goes out of the window, and getting dressed in the right gear becomes less of a luxury and more of a necessity. Good quality clothing appeals to The Rake’s inner narcissist, yet some people in certain locations rely on it to perform important daily tasks, or, in some cases, even to survive.

Laurie Skreslet is one such example. In 1982 he became the first Canadian to summit Mount Everest, during an expedition that saw four climbers in his entourage die during an icefall. Since then he has led 30 quests at Everest, and he’s long been conscious of how his clothing can benefit him in more ways than one. According to Skreslet, “There’s been many a night when bad weather forced me to bivouac on the side of a mountain with only my Goose parka as a sleeping bag. I survived because of that parka.” The piece of outerwear he’s referring to was made by the extreme-weather specialists Canada Goose, a brand that he and countless other explorers, arctic emergency forces and cold-weather film crews have long been reliant upon.

There’s something appealing about functional clothing. The Rake has for some time championed the finest tailors from Savile Row to Naples, artisans who create exceptional pieces of clothing with not much more than their bare hands. But suits are not functional. They aren’t warm, they can crease easily, and like a middle-aged banker they require a lot of work to keep them in good shape. Functional clothing, however — and particularly outerwear — makes more sense. Regularly derived from the military, clothes that once served a specific purpose — i.e. field jackets, bombers and parkas — can now aid the wearer in complementary ways, with multiple pockets, waterproof fabrics and, in some cases, removable padded linings resulting in a jacket that will adapt to the seasons. Canada Goose, who celebrated its 60th-anniversary last year, has always specialised in producing the latter, parkas that put function and practicality before style, a noble concept if ever there was one.

Take, for example, the brand’s signature Snow Mantra jacket. It has been field-tested in the coldest places on Earth to withstand temperatures of -30°C and below. It is constructed from Arctic Tech, a custom-made, advanced polyester/cotton-blend fabric and consisting of a hard-to-fathom 270 individual components, a number that might make more sense in a mechanical watch or a car engine. Spencer Orr, the V.P. of Merchandising and Product Strategy at Canada Goose, says: “It’s not just the shell and the down bag put together. There’s a shell, then an interlining, then a lining, and another interlining, and a hanging lining, and every single piece that goes into every different size of Mantra is a different size. You can imagine how much handcraft goes into that… every cut, fold and stitch is precise and guided by decades of experience. No detail is overlooked.” The Snow Mantra “was built to be essentially a working survival garment. A garment designed for almost an industrial use for people who work in the most extreme conditions in the world. It’s earned the claim as the warmest parka in the world. That competency and those genetics find their way into everything that Canada Goose builds.”

Indeed, functionality has been at the core of the brand since it was founded six decades ago in a small warehouse in Toronto. Dani Reiss, the Chief Executive, tells The Rake how it began: “It’s a third-generation family business, and my grandfather founded it in 1957. He was an immigrant to Canada, like many Canadians, and he worked as a fabric cutter in factories before eventually opening his own small shop, employing about eight people or so, and sewing garments for local customers. Some of the employees who worked with him then still work for us today.” The idea of loyalty and authenticity, Dani says, is key to the brand, and it’s evident during a stroll around their main manufacturing plant in Toronto, where the mood is jovial and people seem genuinely proud to work there in the large, light-filled factory. Many of the employees are Canadian, and it seems the patriotic associations evoked by the brand are important to both employees and consumers. Reiss says: “We decided around the year 2000 to stay ‘made in Canada’ definitively, and not only to stay ‘made in Canada’ but to become a champion for it. Since then we’ve built what we believe is the largest manufacturing infrastructure of its kind in this country.” It’s certainly large. 2016’s revenue was $290.8 million, and early in 2017 Canada Goose went public, with a market value in the autumn of last year pushing $2 billion, according to Bloomberg. How did this happen? Reiss has a theory. “People want the things that perform out there in the real world,” he says.

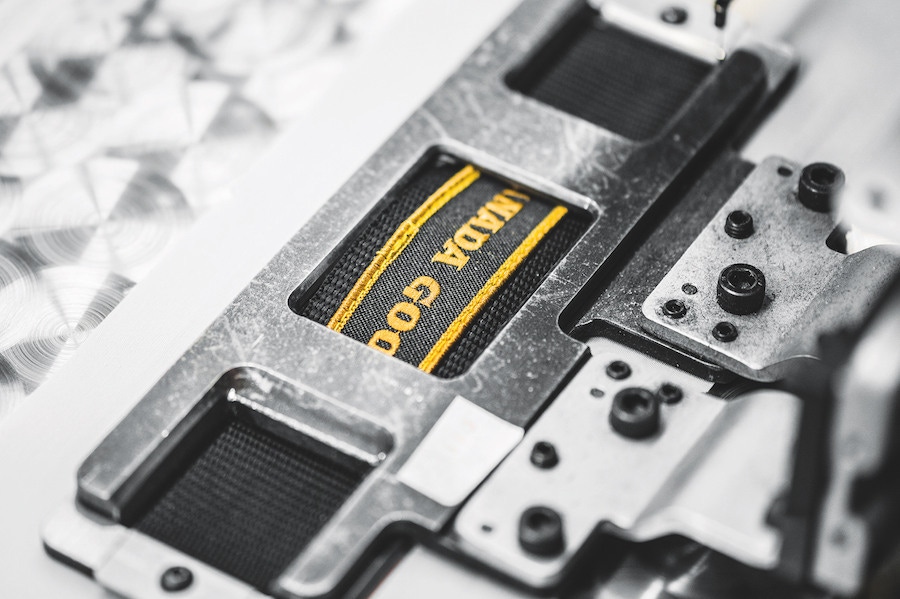

A certain amount of the brand’s success can be attributed to its authenticity, then, but its well-chosen collaborations also explain the smooth transition from the summit to the streets. Reiss says that, “Last year we collaborated with Vetements, Opening Ceremony, Marc Jacobs and October’s Very Own”, the label of fellow Canadian Drake. Streetwear brands have long used collaborations to entice new audiences and further their legitimacy and ‘want factor’, but it’s a relatively new concept in the luxury sphere. As many brands are discovering, though, the result is just the same. “[Drake’s] brand and our brand gained global prominence almost at the same time,” Reiss says. “So that was kind of cool. We do stuff with him twice a year. Back in the day he just wore our stuff, with his crew, and then he wanted to collaborate. I think it was our second collab we sold out: [the Canada Goose x OVO Chilliwack bomber featured] all buffalo leather, 24 carat gold-plated hardware, the lining was crazy, it cost $5,000 or something… I imagine it’s on eBay now for a fair bit.”

All it takes is one coat, well executed and in a limited edition, and all of a sudden it’s no longer just explorers in need of warmth who are wearing Canada Goose, it’s the fashion set in search of a label. The visible branding has been key to the rise of Canada Goose’s popularity, in the same way that Stone Island’s or Supreme’s branding have resonated with avid collectors of streetwear. That distinctive red, white and blue disk on the upper arm or chest is not just a signifier of Canada Goose’s prominence in Arctic research, it’s a symbol — it shows that the coat you’re wearing is no regular parka, but an expensive, exclusive garment reserved only for those in the know, although, of course, everyone knows.

Much of the warmth of a Canada Goose coat can be attributed to nature. The bodies are filled with duck down, which, according to Laura Fine, the Merchandising and Special Projects Manager, “naturally provides about three times more warmth per ounce than existing synthetic insulation”. It may be the warmest, lightest insulator available, but the industry faces intense scrutiny from animal rights groups that highlight the treatment of birds in the plucking process. In their 60th anniversary book, Greatness is Out There, Canada Goose state that, “Down from live-plucked or force-fed birds is never used, only down that comes as a byproduct from the poultry industry, and is sourced from a reliable, independent provider”. That notion applies to their coyote-fur hood trims, too, which are said to be the most effective way of keeping the cold at bay in the Arctic, or, indeed, on a regular winter’s day in downtown Toronto.

Similarly, Canada Goose have faced criticism for their continued use of animal fur, which they say they source in an “ethical, responsible and sustainable” way. “All fur is purchased from licensed North American trappers, who are regulated by state, provincial and territorial wildlife government agencies,” Canada Goose say, although in not offering a synthetic alternative, they are undoubtedly turning off a number of potential consumers. But perhaps that is the point. Canada Goose is a brand that prides itself on its authenticity, and it wouldn’t be truly authentic if it didn’t continue to use the same materials it started with decades ago. The most prestigious tailoring brands purposefully don’t veer too far from their house cut, or from the principles laid out by their founders. Canada Goose’s formula hasn’t changed, and while it won’t be for everyone, it at least explains in part how this most functional of brands has gone from a small shed in Toronto to a global billion-dollar business that dominates the high-end performance outerwear market in just 60 years. Global warming may be slowly heating our planet, but that won’t stop people wearing Canada Goose for the next 60.

Originally published in Issue 56 of The Rake. Subscribe here for more.