The Overall Effect and the Call of the Siren Suit

Josh Sims takes a peek inside the overall - that most 'outer' of outerwear - and finds a fascinating history underneath.

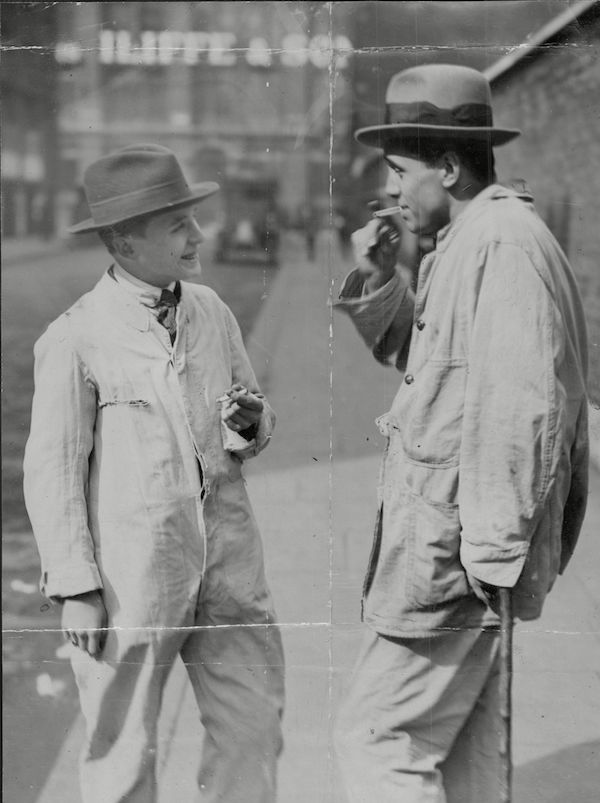

If you’re aiming at a new vision of society, you need a new vision of what to wear in it. Revolution begets sartorialism, so to speak. At least that seemed to be idea of radicals in the early decades of the 20th century, from Ernesto Michahelles (aka Thayaht) - darling of Italian futurism - to the likes of Alexander Rodchencko - doyen of Russian constructivism. What is unexpected, however - given the dissimilarities between the two period-defining movements - is the kind of garment they each settled on as embodying this planned wholesale reorganisation of modern life: a pair of overalls.

Of course, to dress the rise of the workers, such a workmanlike garment - worn by share-croppers, stockers, mechanics and sometimes artists - might be considered the obvious choice. And perhaps the choice of this rather minimalistic, rational and above all practical garment - no need to match top with bottom, plenty of pockets - also hinted at the proposed future world’s preference for suppressing individuality in favour of the collective. Overalls were also anti-fashion - they represented a move against over consumption, of class and wealth display, of change for change’s sake, in favour of function, form and clothing’s first principles. If you are what you wear, then what better way to begin towards a new society than with the overalls’ blank slate?

This may not have been an entirely new notion - as Dr. Flavia Loscialpo of Southampton Solent University’s School of Art, Design and Fashion notes, even Thomas More’s ‘Utopia’ of 1516 described its people as wearing practical, trans-seasonal clothes that “allow free movement of the limbs” and which left them “happy with a single piece of clothing every two years”. That latter benefit may not have come to pass, even if, in 1919, Thayaht originally designed what he called his ‘tuta’ as some kind of protest against the high post-war clothing prices that left most Italians sweltering through the summer in their thick, cumbersome winter clothing. Here was a T-shaped garment - like a t-shirt extended in all directions - that offered the same kind of ease and simplicity of purpose.

As for free movement - given that Thayaht and Rodchenko’s contemporaries were typically buttoned-up and besuited, and that to be otherwise in good company would be considered bad manners, their one-piece proposals seem somewhat prescient in at least one way: overalls surely prefigure today’s ubiquitous, unimaginative, comfort-driven sweatshirt/sweatpants combo.

That grey sloppiness probably wasn’t what either of them were aiming at: more an exploration of the idea that, if so much of life was changing beyond recognition as a result of industrialisation, why shouldn’t clothing go through the same process too? After all, Rodchenko named his overalls ‘prozodezhda’ - a conflation of the Russian for ‘industrial’ and ‘clothing’.

All this logical style must have seemed like a fresh page for style. And certainly Thayaht went to town to push it: a Florentine newspaper published the pattern so anyone could make their own tuta at home - another snub to the fashion system; he made a short film on why it should be the garment for you, for all: “Tutti in tuta”, ‘Everybody in tuta’ was the catchphrase. Come the following summer, some thousand people in Florence were said to be wearing a tuta. The name even entered the Italian language to describe any kind of utilitarian, ready-to-go work garment. The word is still used today.

Ironically, however, the well-heeled almost immediately saw the tuta as the big thing in fashion - not helped by Thayaht’s later decision to license the design to the couturier Vionnet - and demand even pushed up fabric prices. Rodchenko’s constructivist clobber was perhaps even less likely to be taken up as the new mode of dress for all forward-looking people: never really disassociating his garment from the work one did in it - work being a heroic enterprise in Soviet Russia - the intellectual even saw the garment as gender neutral, as a way of suppressing differences between the sexes. Only members of the Russian avant-garde would wear such avant-garde clothing.

And yet, arguably, while fashion would produce endless versions of overalls over the coming decades, the garment continued to embody an inherent sense of the progressive. When Winston Churchill has his own one-piece ‘siren suit’ tailored for him by Turnbull & Asser - something he could throw on over his pyjamas when air raids forced him into a bunker in the wee small hours and still leave him looking respectable, with plenty of pockets for his cigars - it became a signature of his eccentricity and a sartorial rallying cry. But, although Churchill would continue to wear them after the war’s end - mostly to paint or lay bricks in - his siren suits didn’t transcend their perceived radicalism to form a template for a new form of general dressing. The mass of manual workers, it seemed, just didn’t aspire to dress like manual workers.

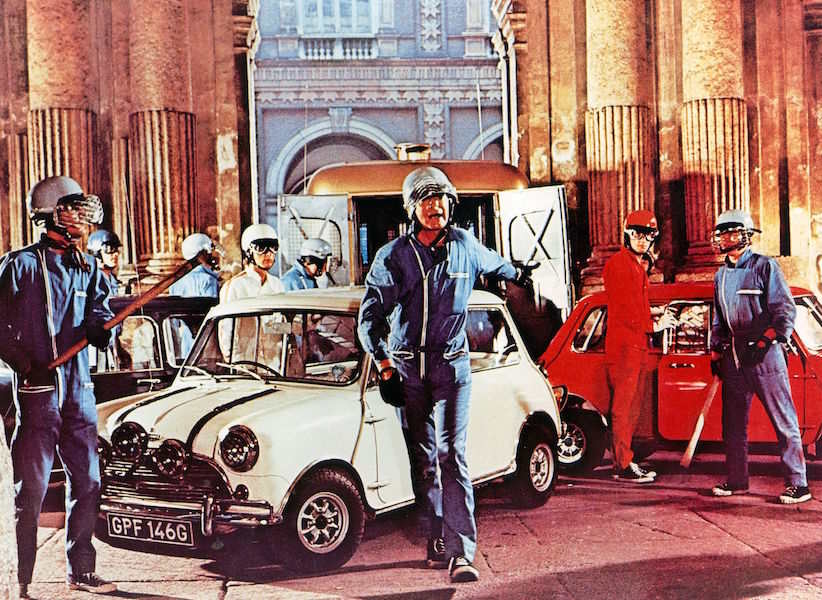

Indeed, while manual workers of all stripes would continue to wear overalls as job-specific clothing, still a return to something like the tuta or prozodezhda would be made by those wishing to impart a vision of tomorrow in art - only this time that vision would be decidedly dystopian. Whether in film versions of Orwell’s 1984 or of Burgess’ A Clockwork Orange, overalls keep getting zipped up again and again to suggest personality negated or boundaries crossed. Something to ponder on your next visit to Kwik Fit.