The Artist's Life And The Meaning Of Death

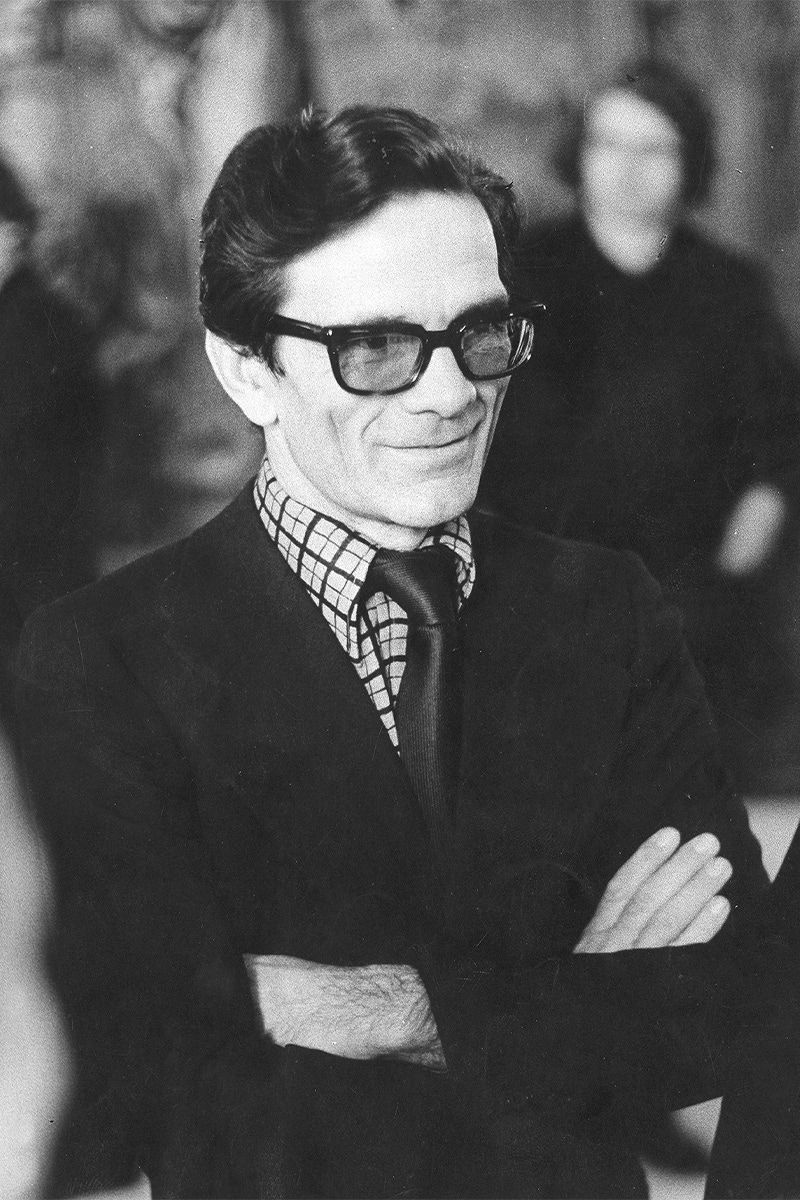

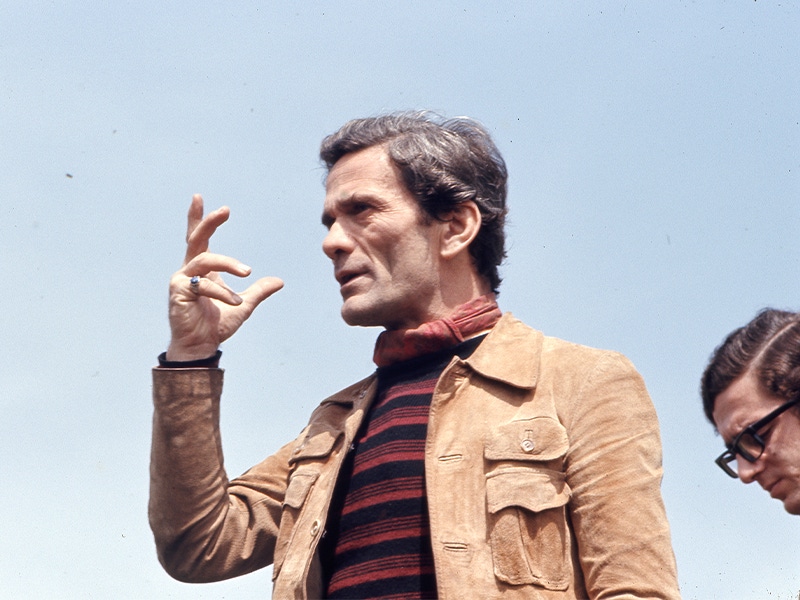

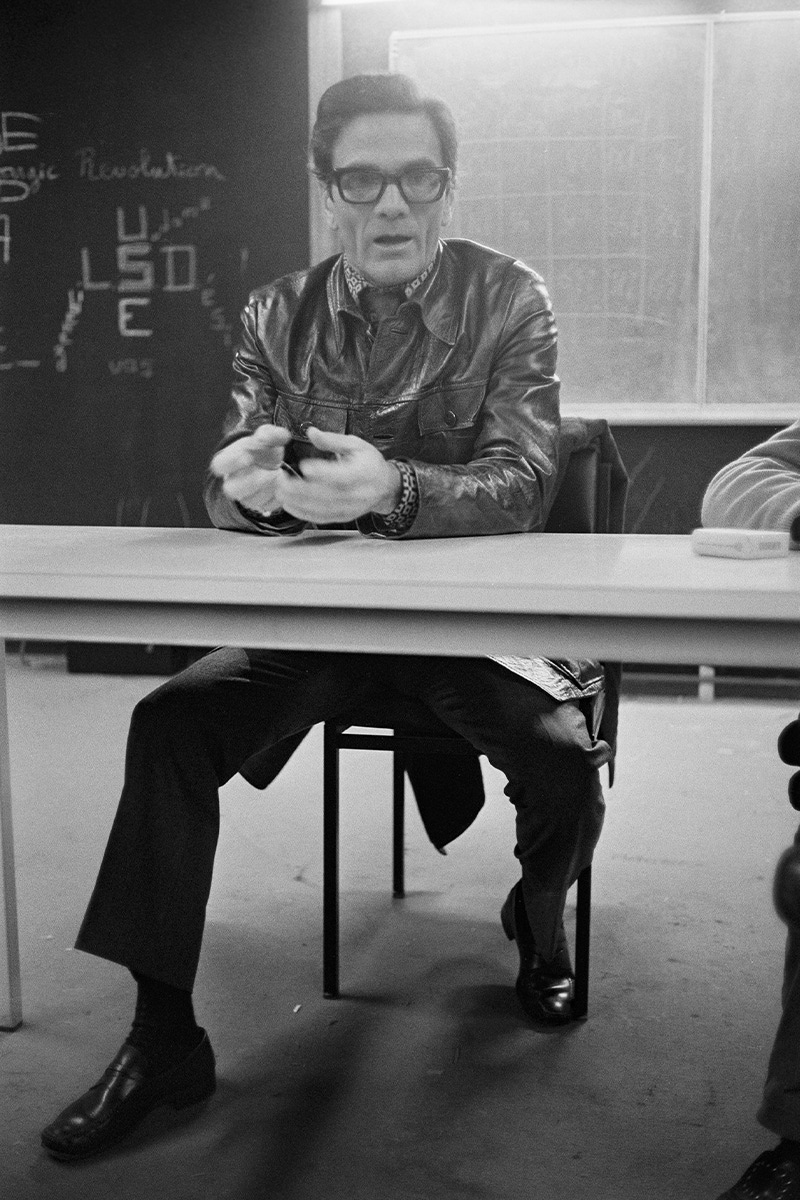

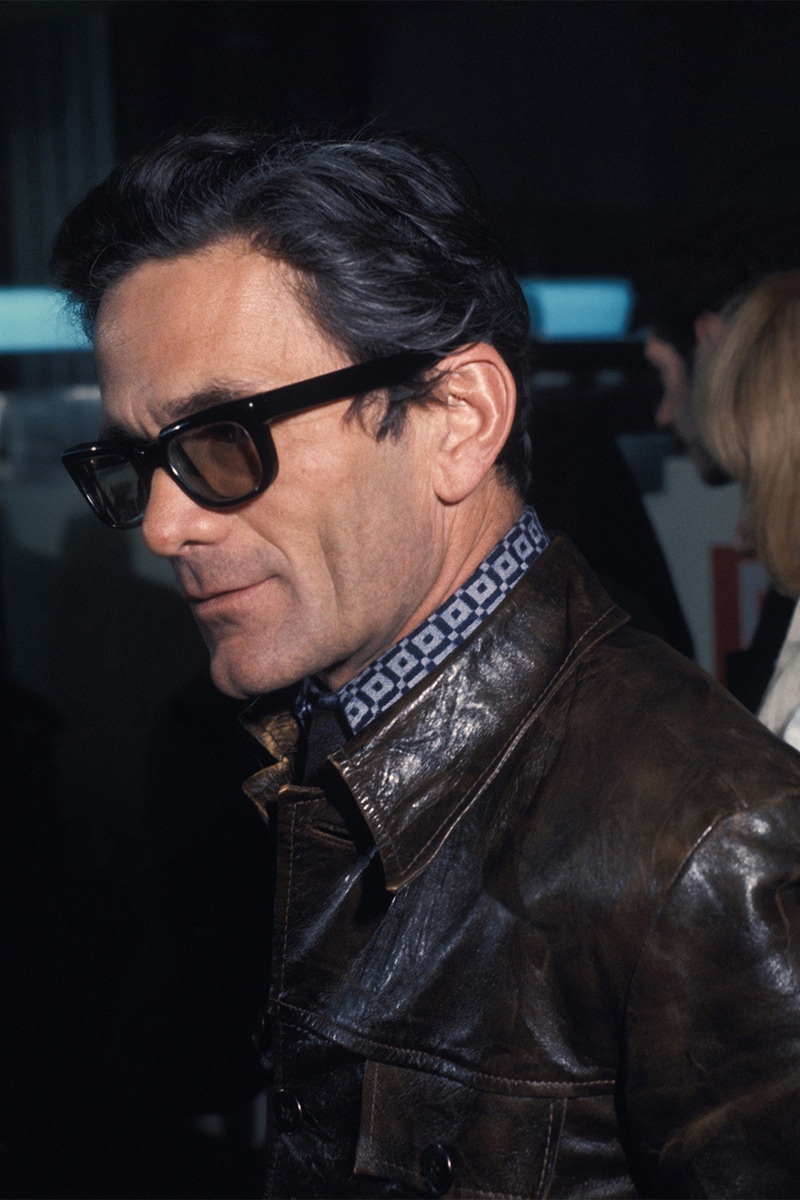

On November 23, 1975, Pier Paolo Pasolini’s last movie premiered at the Paris Film Festival, and immediately garnered a reputation as the most gruelling, and least watchable, motion picture entertainment of all time. Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom, took the lubricious catalogue of torture and depravity lovingly detailed in the Marquis de Sade’s infamous 1785 novel and transposed it to Mussolini’s Italy, where a group of eminent libertines confines a group of teenagers in a villa and subjects them to... well, here are some ‘highlights’ from the film’s Wikipedia page: “Three-way intercourse... eating his faeces with a spoon... the President leaves to masturbate... branding, hanging, scalping, burning.” “Literally nauseous,” read one review; Mary Poppins, this clearly wasn’t. Pasolini wasn’t around to see the film’s unveiling or the appalled reaction; his mutilated body had been found in a vacant lot in Ostia, a suburb of Rome, three weeks before. The assumed killer was a 17-year-old hustler that the 53-year-old had apparently cruised. People were quick to attribute a death wish to Pasolini, which Salò made abundantly, lip-smackingly manifest (“He has become the victim of his own characters,” opined his fellow director Michelangelo Antonioni). But while he was disgusted with the direction post-war Italy had taken — he saw the country’s boom as an irreversible blight, turning the masses into mindless consumers and creating a slavish monoculture — Pasolini was no nihilist. In fact, he’d spent his life wriggling free of any -isms that would claim him for their own.

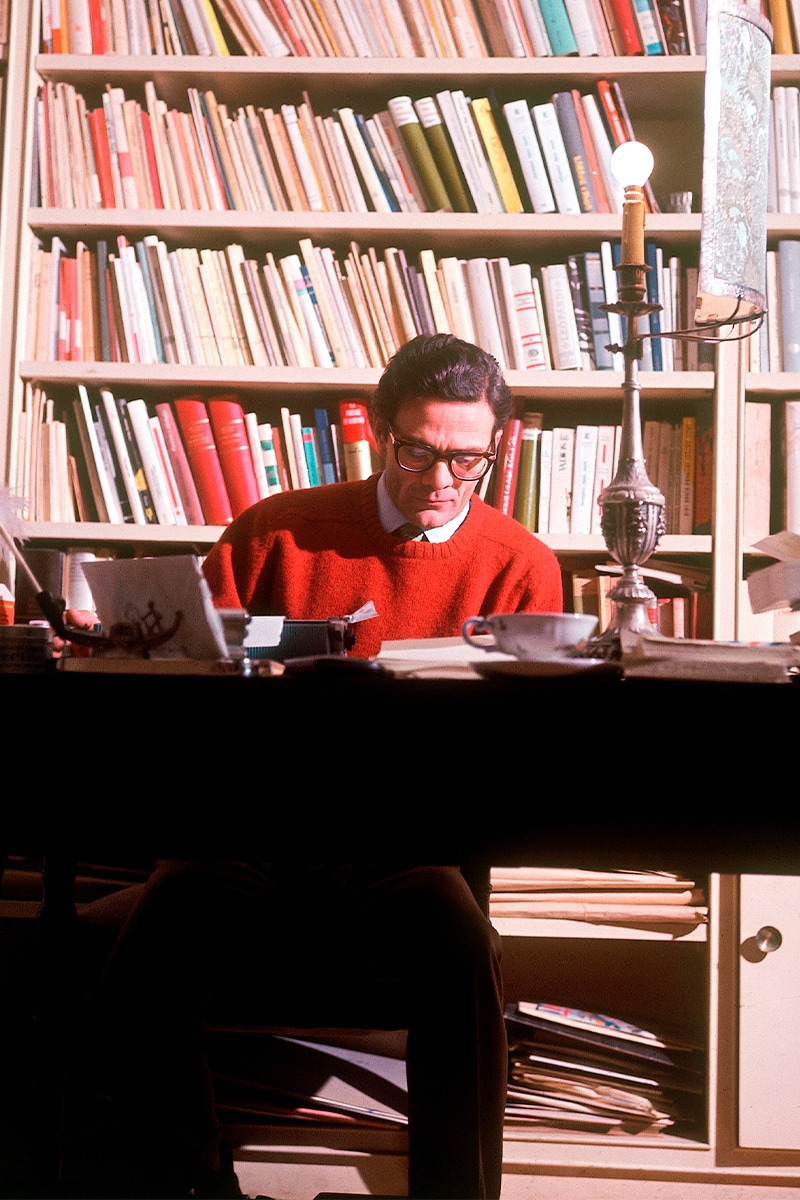

Pasolini’s impact as a filmmaker is in inverse proportion to the brevity with which he practised it — a mere 14 years. He was born in Bologna, the son of an army officer, whose re-postings necessitated a peripatetic childhood; he found refuge in literature, first writing poetry while living in his mother’s native Friuli province, near the border with Austria and the then Yugoslavia, then establishing himself as a novelist in his thirties with 1955’s The Ragazzi and 1959’s A Violent Life, in whose tales of brutish street life in the slums of Rome he formed his own distinctive voice — gritty, fatalistic, almost flip — and developed his pugilistic skills when the books were traduced by the right, who attempted to censor them, and the left, who complained that the working-class characters weren’t exalted enough (Pasolini’s repeated willingness to put up his dukes made him that rare thing: a public intellectual who was loved more by the public than by other intellectuals).

Motivated and inspired by this anger, Pasolini embarked on a new series, the ‘trilogy of death’, of which Salò was to be the first instalment (one can only imagine how he would have attempted to trump himself with parts II and III). His own death put paid to that, and initially seemed like an open and shut case — Pasolini had been availing himself of rough trade for years — but (this again being Italy) things have got murkier over the years. Giuseppe Pelosi, who was convicted of battering Pasolini to death and running him over in a stolen Alfa Romeo after, he alleged, the director indicated his willingness to sodomise him with a stick, retracted his confession, hinting at deep-state involvement by neo-fascist cells with links to the secret services. They were allegations that seemed all too plausible after the subsequent ‘Years of Lead’ in Italy, with ‘kickback city’ scandals and Mafia corruption infecting an entire political class, and the bombing of Bologna station, which killed 82, by the same unholy neo- fascist-intelligence alliance. Whatever the truth, it’s certain that, had he lived, Pasolini would have trained his implacable eye on the vagaries of modern Italy, stirring up trouble and making a ton of mischief.

Read the full story in Issue 88, available to purchase on TheRake.com and on newsstands worldwide now.

Subscribers, please allow up to 3 weeks to receive your magazine.