THE BIG BANG

‘In the future, everyone will blame the eighties for all societal ills,’ said Peter York, the author and cultural commentator. Are the 1980s fair game? Was the decade of power suits and voodoo economics a gaudy omen or wilful anachronism? Stuart Husband backcombs his hair, fishes out a designer label, and takes a trip down memory lane…

It was when I was whisked past the queue at Area, one warm but windy Manhattan night in 1985, that I finally understood how much louder and larger the eighties were than the preceding decades. I was on a journalistic assignment with the group ABC — who by then had ditched their early eighties pomp in favour of an edgier and far less successful iteration as a garish, LinnDrum-tastic disco troupe, complete with cartoon avatars — and our cachet (and accents) meant we were spared the line, not to mention the daunting $15 entrance fee, and granted V.I.P. entrance to a place that, as The New York Times columnist Frank Bruni wrote, “was less a dance club than a sanctum; to get inside was to be baptised, consecrated, canonised”.

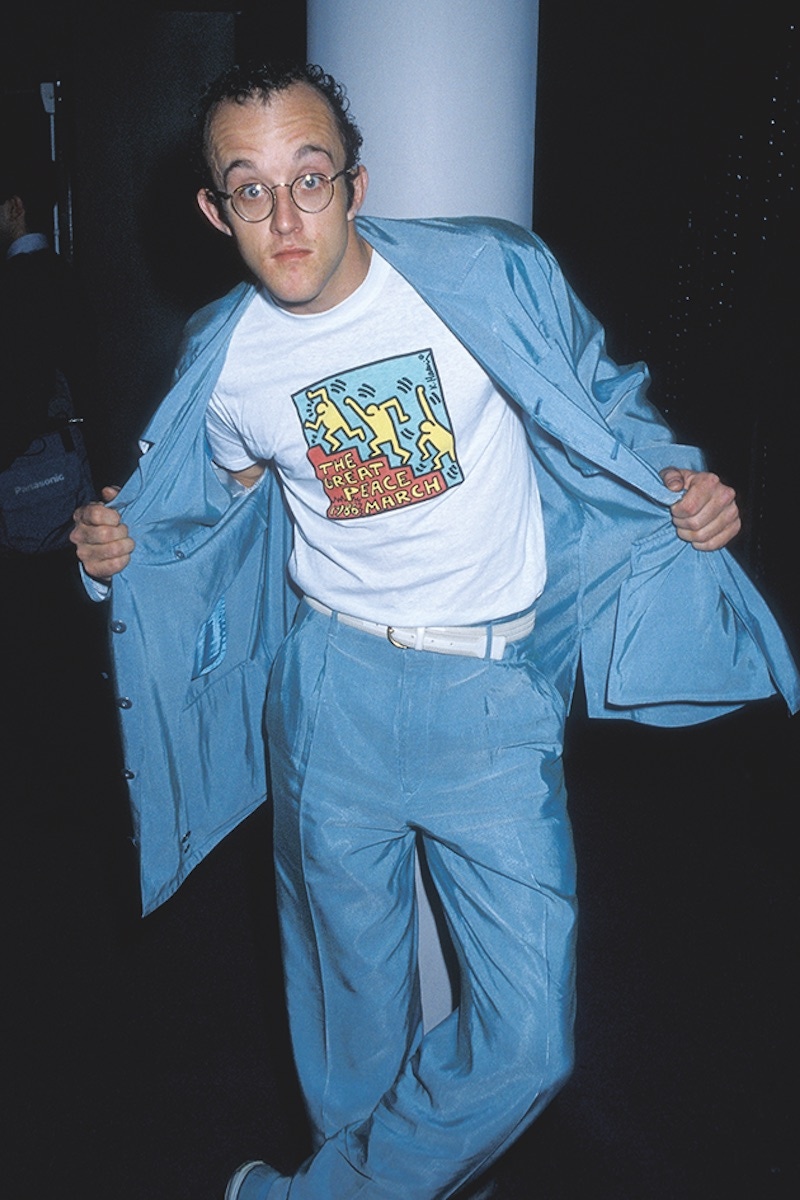

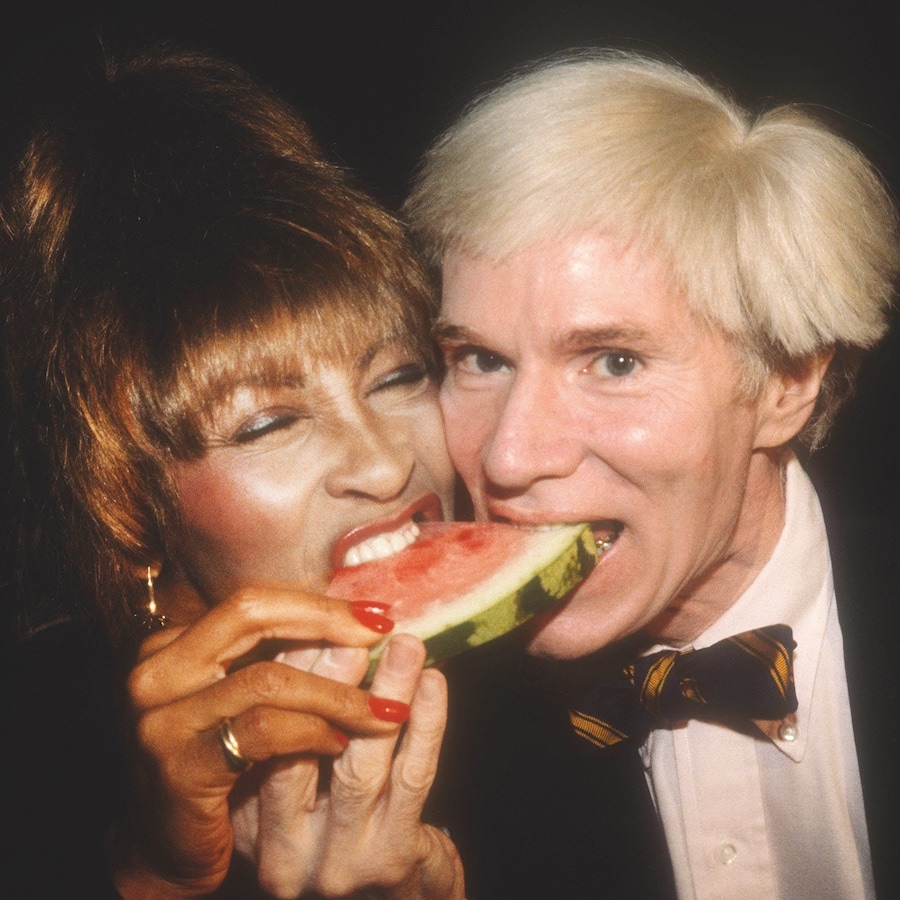

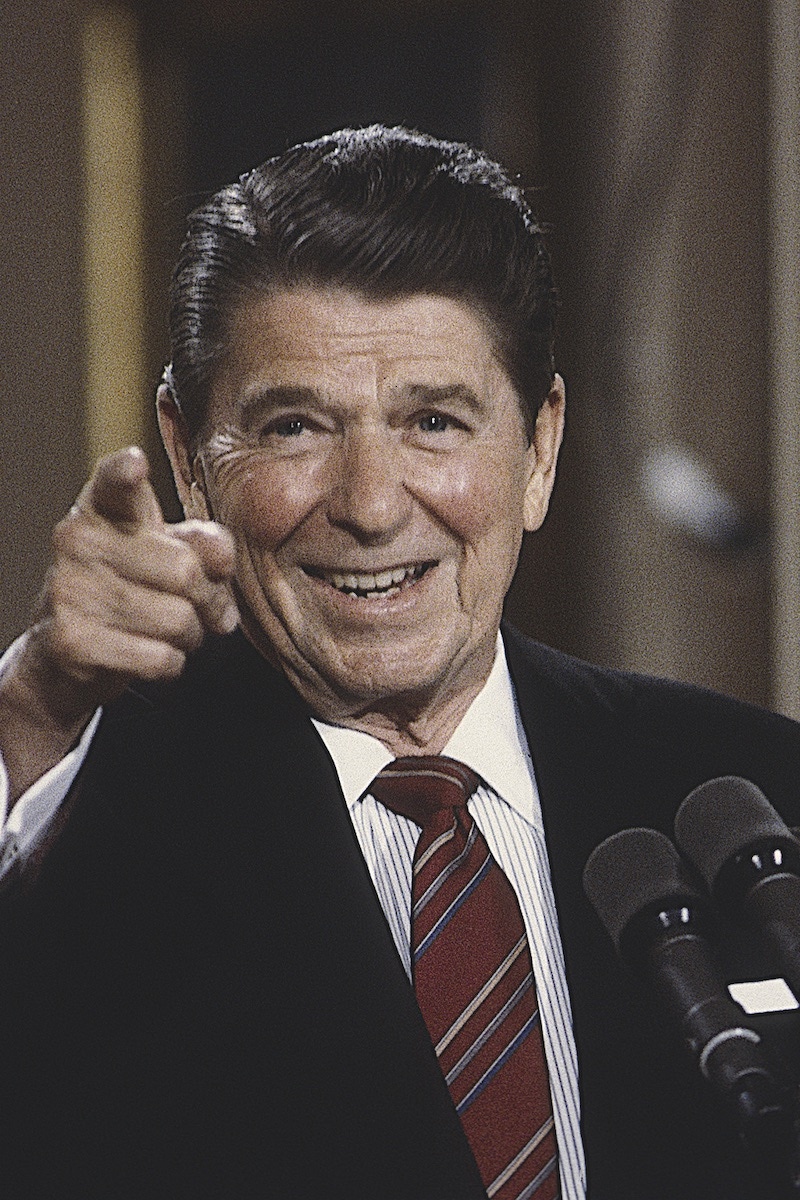

Area, along with other nightlife meccas like Paradise Garage, Danceteria and the Limelight, epitomised the new energy of New York, a city that had hauled itself back from the brink of bankruptcy at the start of the decade and was now partying hard, fuelled by stimulants both established and novel (cocaine was everywhere, ecstasy was just making its arms-aloft presence felt), but also by new money. Various Big Bangs set the eighties pace — there was the deregulation of the City of London in 1986, driven by Margaret Thatcher, which produced a free-for-all as brokers, jobbers and the City’s traditional merchant banks merged and/or were acquired by much bigger U.S., European and Japanese banks (and which created the bonus culture, along with an estimated 1,500 millionaires), while in the U.S. there was Reaganomics, President Reagan’s heady cocktail of laissez-faire economics and whopping corporate tax cuts. “There’s a Big Bang in the City/We’re all on the make,” as Pet Shop Boys put it in their paean to the new rapaciousness, 1988’s Shopping. And there, in the heart of Area, momentarily distracted from the star-spotting as I passed various roped-off banquettes — was that Madonna? (no); was that Andy Warhol? (yes) — I was pulled up by an all-too-apposite symbol of eighties excess: the club’s most notorious flourish, a massive tank full of dwarf sharks, casting their predatory eyes on the fun and frolics occurring in the establishment’s sepulchral corners.

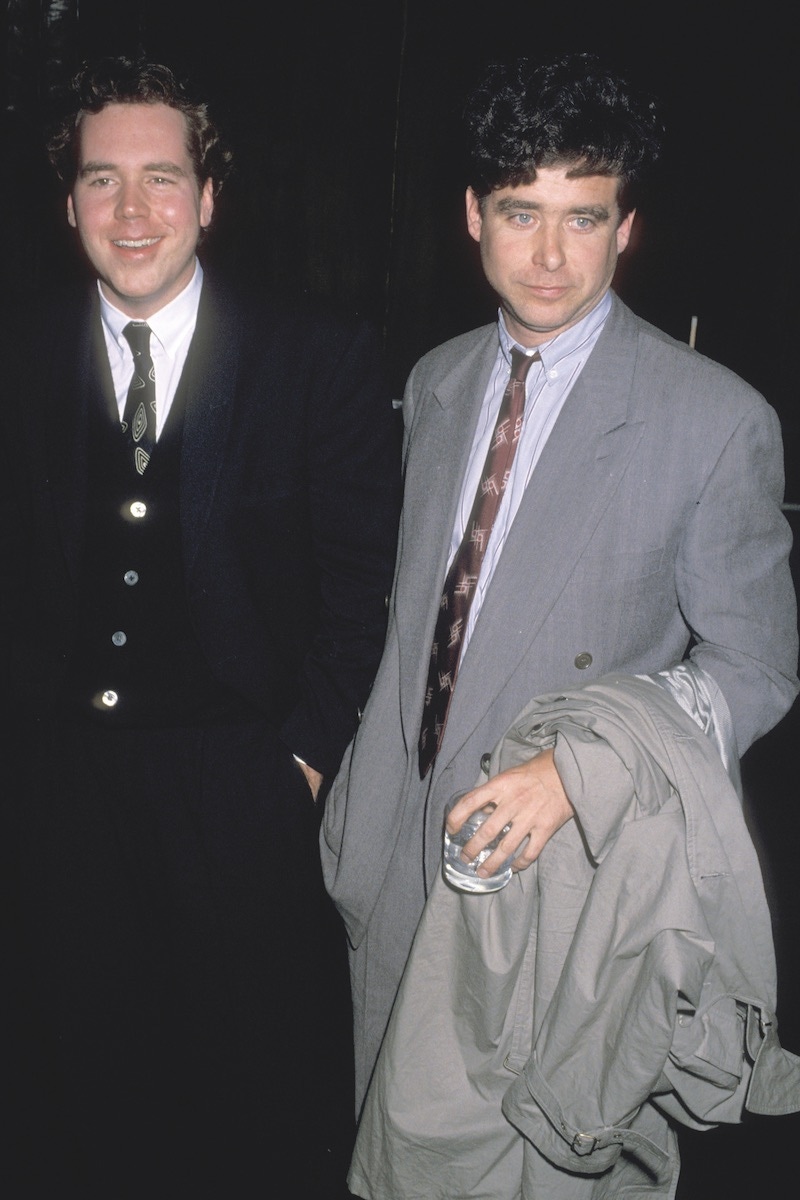

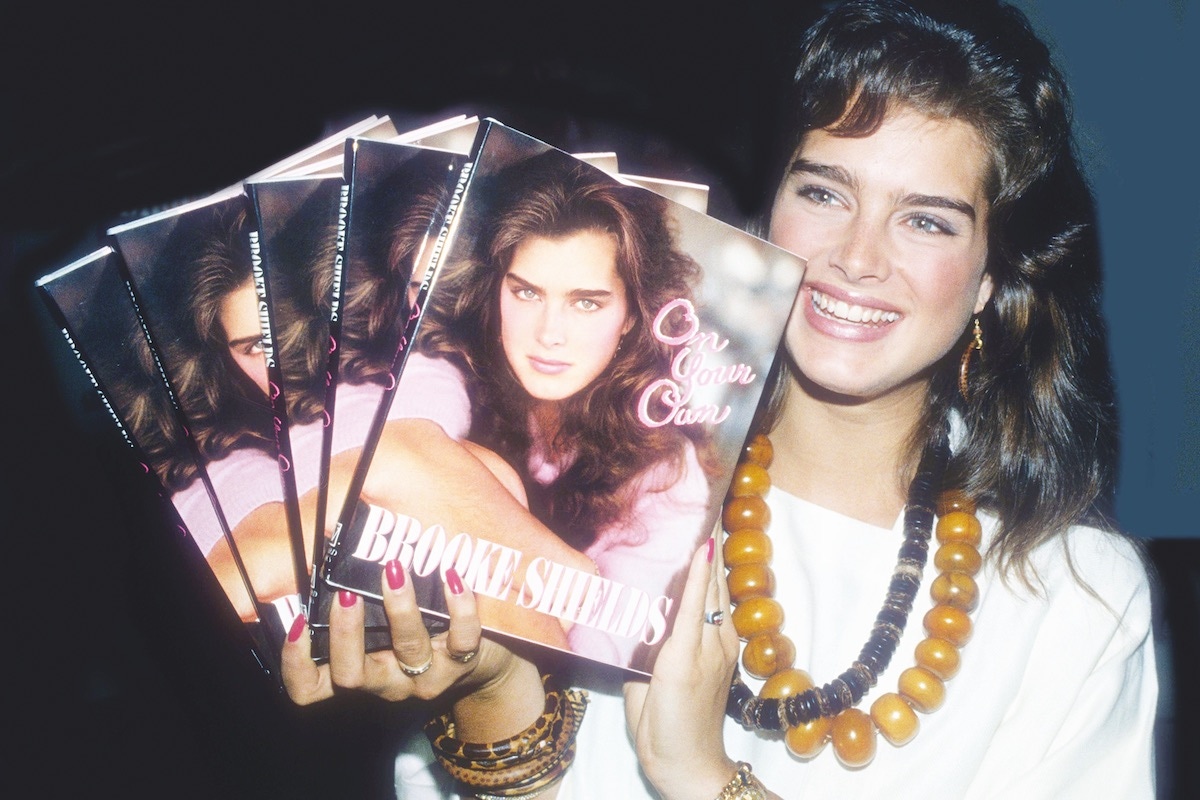

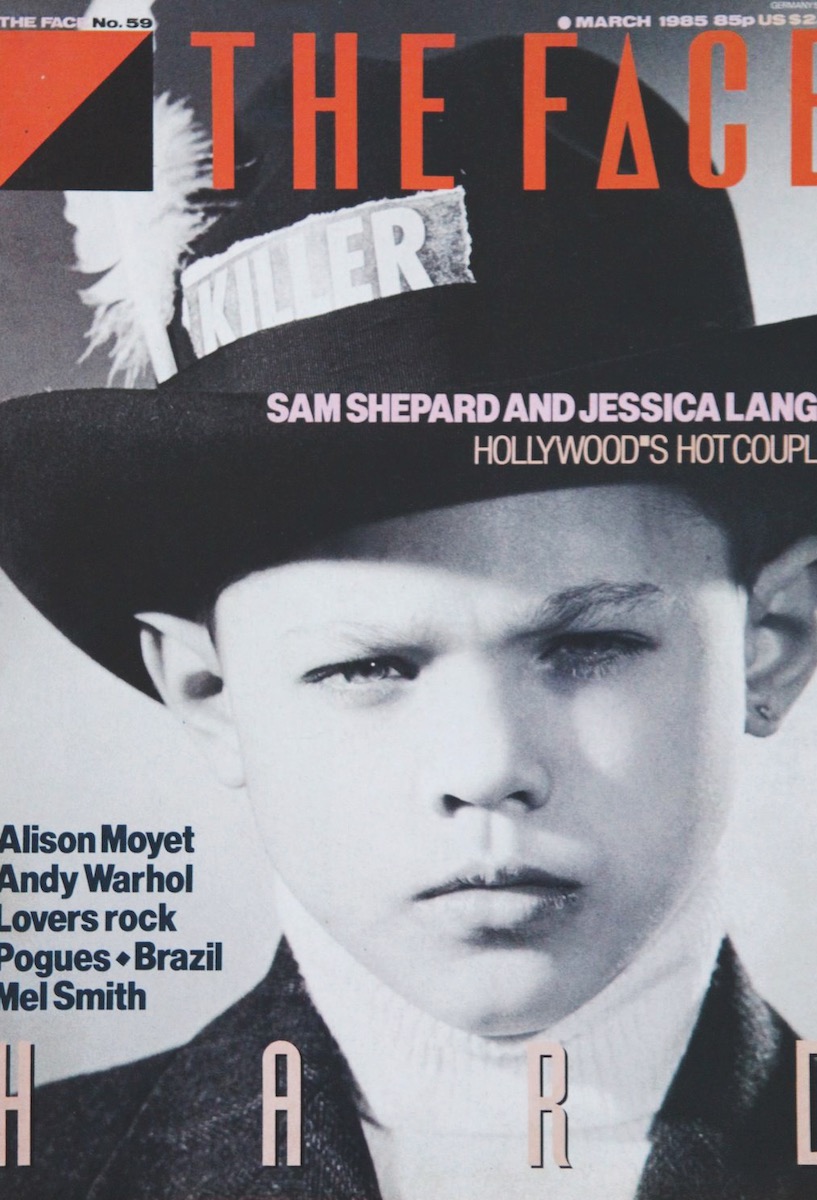

But there was another eighties explosion that proved crucial to the fostering of the decade’s self-image: that of the media. With the launch of The Face, published by Nick Logan in 1980, and the resurrection of Vanity Fair three years later, the term ‘style magazine’ came into parlance, and the hedonistic, entrepreneurial generation that came to define the eighties — in music, fashion, art, finance, architecture, design, just madly posing, whatever — was exhaustively documented and celebrated. I played my own, minuscule, part in this, joining a music magazine fresh out of college (actually, not even finishing college; jobs were thick on the ground and light on the entrance requirements in those days), and covering the rise of a bunch of disparate pop stars, from Marc Almond to Boy George and Bananarama, all of whom seemed alternately thrilled and bewildered to be raking it in and to be asked — by the newly minted glossy pop weeklies, or the hastily assembled features teams on the tabloids and broadsheets — what their favourite colour was or who their best-ever snog had been with. Expense accounts ballooned, junkets mushroomed — I’d been put up in the Chelsea Hotel on the ABC trip, the romance of which was only slightly soured by the fact that I spent each night perched on a stool wielding a baseball bat, as hundreds of prodigious cockroaches scuttled out of the hole in the shower stall — and restaurants, clubs and cocktail bars started springing up to cater to this new elite.

“The eighties gets rather a bad rap today — you know, all backcombed hair and ‘mobile’ phones the size of wheelie-bins,” says the tailor and designer Timothy Everest, who started the decade working for Tommy Nutter, and ended it with the launch of his own atelier (he now heads up MbE, a line of bespoke casual pieces including Harringtons and chore jackets). “But I remember Tommy saying that it was the first time since the sixties that people had that real gung-ho spirit; they really felt they could do anything. Something was happening every night, and if it wasn’t, you went out and did it yourself. It was really exciting.”

“It was suddenly like we’d come out of the darkness of 1970s punk to vibrant designer noise and images,” the P.R. guru Lynne Franks — inspiration for Jennifer Saunders’s Eddie in Absolutely Fabulous — reminisced to The Independent. “It was all about ‘designer’ with a big D: Designer labels, Designer drinks, Designer architecture, Designer causes, even Designer spirituality.”

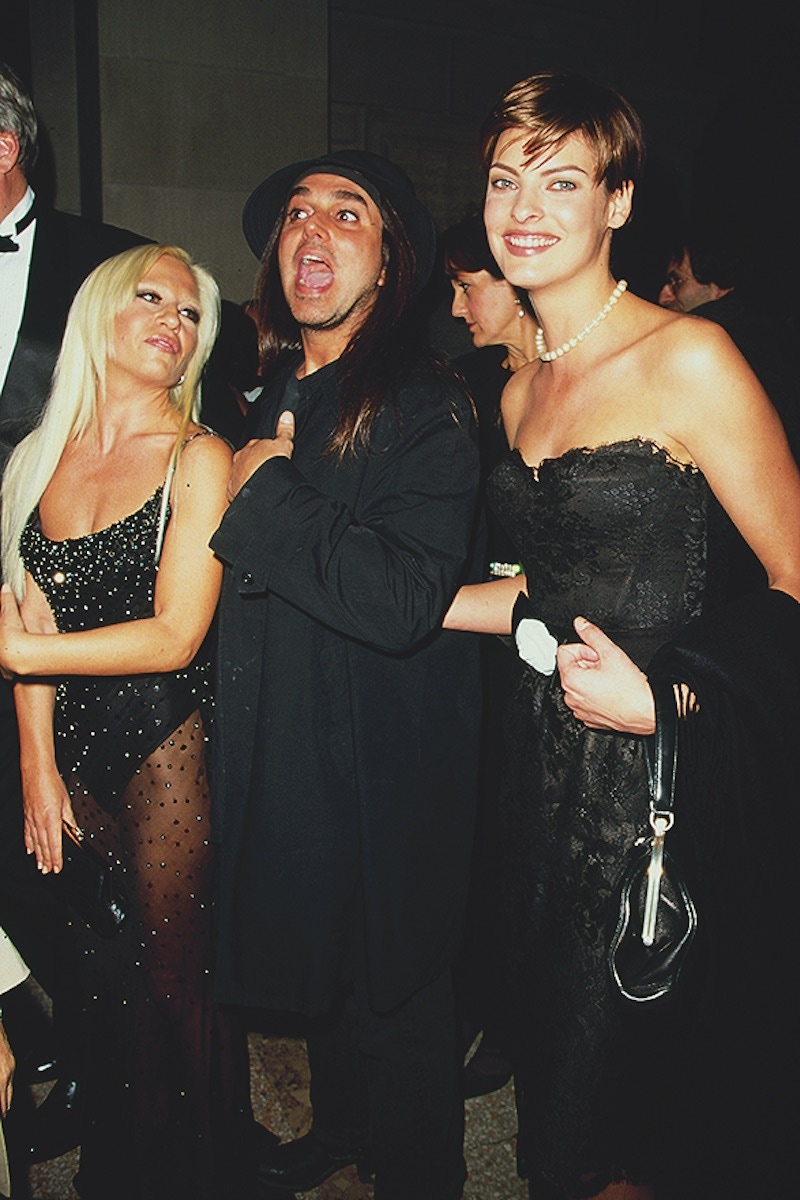

Doonan wanted to break down the dividing line between uptown and downtown with such spectacles. “The line was much more pronounced than it is now,” he recalled, “but the eighties were when the cracks started to appear.”

The decade saw other fault lines appear that were ripe for exploitation. “People who had once merely gone into professions now started seeing themselves as brands, and took advantage of this fantastic amount of new media with its jaws agape, which demanded constant feeding,” says Peter York. The prefix super- had yet to be systematically applied to chefs or models, but the groundwork was being laid. In London, Marco Pierre White lured the beau monde to the far-flung environs of Wandsworth Common and Harvey’s restaurant, where they savoured his legendary nougat glacé and his wild-haired, cleaver-swinging persona, trademarked on the cover of his debut 1990 book, White Heat, and emulated by celebrity pretenders ever since. Inevitably for a decade that was so much about surface and gesture, models became as feted as pop stars and actresses, with every one of their gnomic utterances captured and strategic alliances analysed. Elle ‘The Body’ Macpherson married Gilles Bensimon, photographer and creative director of Elle, in 1986, a year after he’d shot a famous cover of her with zinc slathered across her nose (they were divorced before the decade was through). Linda Evangelista married Elite Models executive Gerald Marie in 1987, a year before she cropped her hair and rendered backcombing redundant at a single stroke, and two years before she became the face of Versace. Paulina Porizkova, anointed “the model of the eighties” by Photo magazine, married Ric Ocasek of The Cars in 1989. Carla Bruni became the face of Guess jeans in 1988 (Claudia Schiffer would succeed her), and started dating Eric Clapton the following year. Naomi Campbell was the first black model to appear on the cover of French Vogue, in 1988 — a year after being romantically linked with Mike Tyson. Cindy Crawford began hosting MTV’s House of Style in 1989; her Revlon contract — and marriage to Richard Gere — would come two years later. The nascent supermodels (the term would eventually stick in the early nineties, when Helena Christensen and Christy Turlington joined the gang) provided a welcome shot of old-school Hollywood glamour at a time when Hollywood itself was going through a somewhat frowzy phase, and there was a steely quality to their inexorable rise that chimed with the decade’s preoccupations, exemplified by Evangelista’s famous quote that she didn’t deign to get out of bed for less than $10,000 a day, but also in Campbell’s opining that “I make a lot of money and I’m worth every cent”.

That was a not-so-humblebrag that you heard a lot in the eighties, but it had a special potency on the trading floors of Wall Street and the City, where fortunes were made and lost overnight. “In America they’d called Reagan’s policies ‘voodoo economics’, but the same held true for the markets around the world,” says Peter York. “It was no wonder that finance people began mingling with what everyone called ‘the creative industries’ — for the first time, they’d become one of them.”

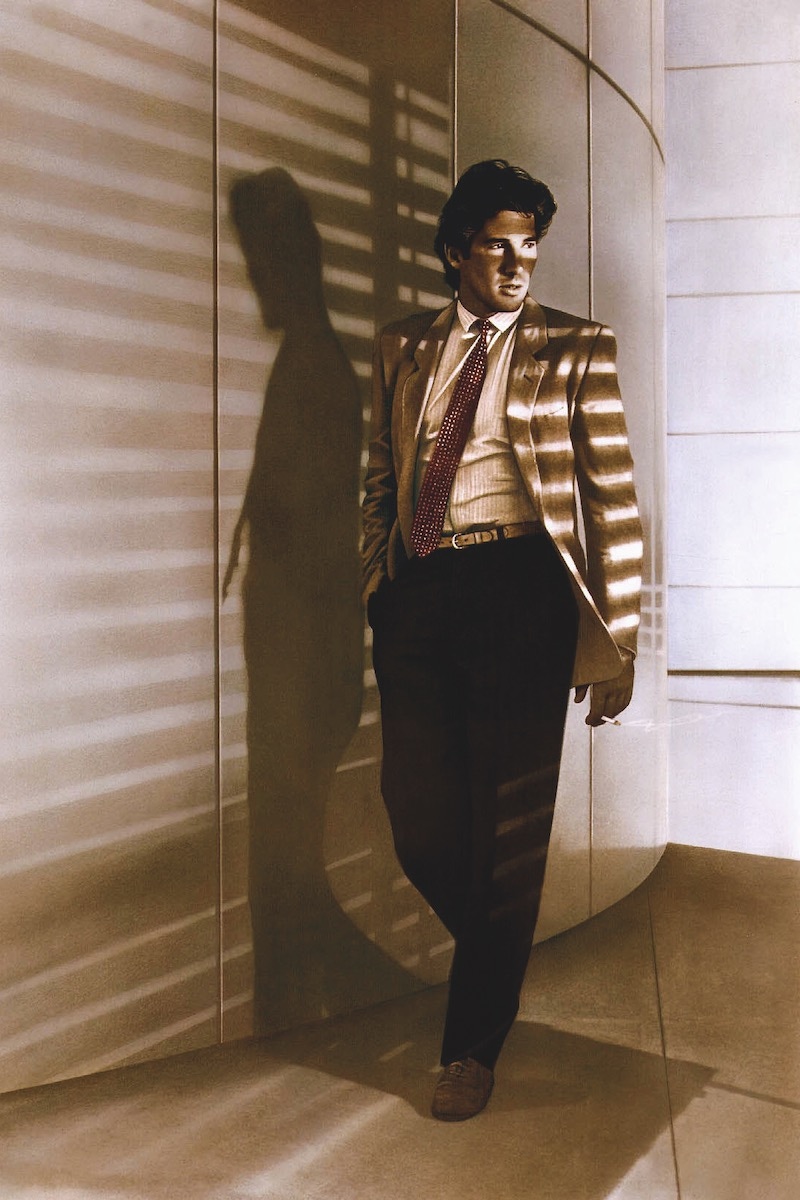

Here, as elsewhere, the right image was crucial. “At the start of the decade, everyone wanted that early Armani deconstructed matinee idol look,” says Timothy Everest. “American Gigolo came out in 1980, and people were channelling Richard Gere. But as the serious money started being made, the power suit became the uniform — navy or grey chalkstripes, Prince of Wales checks, contrast collar or bold-striped shirts, cutaway collars, statement ties, braces, brogues. There was a pretty decadent period around the mid eighties; we knew young guys on the trading floor who’d wear full-length mink coats. It was an expensive lifestyle to maintain — an entry-level Hugo Boss suit cost about £300 then, which would be, what, over £1,000 now? But everyone seemed so confident. Of course, cocaine helped in that regard.”

Cars were another essential part of the armoury. “The red Porsche Targa 911 turbo was the classic city car of choice,” says Everest, “or the Ferrari Testarossa, because it was so modern-looking. Failing that, a Golf GTI Mk1 in Mars red with the double-stripe detailing, or the Mercedes S Class in grey. Driving old cars was quite cool, too; I had a two-door Mercedes coupé, and you’d see lots of architects driving Bentley Continentals. But I always had the feeling that a lot of the stuff the City guys were doing at the time was just one step away from being illegal. It was very much a built-on-sand kind of mentality. And then, when the crash came, a lot of them simply disappeared, or ended up dishwashing or something.”