The Fire in His Belly

Billy Joel’s best songs are an intriguing, genre-defying mixture of melody, musicality and lyrical brimstone. What’s with the attitude? Is he a great-but-flawed entertainer or forever just a Bronx Joe made good.

You think you know Billy Joel, but you don’t know Billy Joel. There’s an easy way to prove it: go to YouTube and search for ‘Attila’. You’ll hear a cacophonous late-sixties version of heavy metal led by over-amplified organ and see a picture of two longhairs in armour standing in an abattoir. One of them is the organist, and he’s Billy Joel.

Most musicians have a past they’d rather forget, and this is Joel’s. He went through a succession of cover bands and failed beat bands, then the terrible Attila, and all of it to show that he wasn’t made for his times. In truth, though, he wasn’t really made for any times, which is both a blessing and a curse for an artist. The songs that made his name — Piano Man and Captain Jack, released in 1973 — were character sketches that might have been excerpts from a Broadway show. The big ballads that made him a bit of a joke for a long time, such as Just The Way You Are, were equal-parts Sinatra-ready tributes to the Great American Songbook and seventies soft-rock schmaltz. With them came punchy little numbers, like Only the Good Die Young, that veered into Springsteen epic territory, and the rock ’n’ roll and doo-wop pastiche of It’s Still Rock and Roll to Me and Uptown Girl. And that’s before we get to We Didn’t Start the Fire, which could have been the work of some eighties alternative-rock band contemporary of R.E.M.

It’s partly down to the fact of writing on the piano — Elton John is equally hard to place, and even Coldplay have the same confusing effect — but Billy Joel really is a curious figure in pop, a collision of nature and nurture, contradicting impulses and unusual driving forces. For a start, as his return to the form in later years reinforced, he’s really a slumming classical pianist, a proper child prodigy who started playing at four. His half-brother, Alex, is a prominent European conductor, his father an equally gifted musician, and his mother the daughter of a long line of English intellectuals.

Billy, however, was born in the Bronx, and raised in the perfectly named Long Island suburb of Hicksville. That father, originally from Nuremberg in Germany, left in his son’s teens for Vienna, and Billy turned from chess and piano to small-time hoodlumry: sniffing glue, petty theft, leather jackets. Picked on for his Jewish roots, he briefly took up boxing, which left him with a broken nose that never set properly. Things might have gone badly for him, but he was lucky: this was the sixties, and pop music saved him. He saw The Beatles on The Ed Sullivan Show and realised there was a place for a guy like him. “That was it,” he reminisced to Q magazine in 1987. “They didn’t look like Hollywood, they weren’t all gleamy. You couldn’t take away the fact that they were these working-class guys. And they were smart arses.”

By the time he noticed that playing in bands, even his cover groups The Echoes and The Hassles, made the girls look at him differently, he was all signed up. Then he hit a wall with the arrival of psychedelia. The drugs didn’t work for him, and he suspected there was nothing behind the mind-expanded lyrics. The failure of Attila was a sign that he was not going to succeed by following fashion, and a first solo album was a disaster, so he retreated to a piano bar in California and plied his trade under the name of Bill Martin.

Either he found himself there or he was lucky enough to be found, but his second album, Piano Man, distilled during his time playing for passing trade, was a proper success. As much as anything in his career, it defined the parameters of his talent: lyrics that tell a story but above all a focus on melody and melancholy, equal parts Cole Porter and Ray Charles. And if you could hear the musical virtuosity and sheer prettiness of Paul McCartney, there was also the attitude of John Lennon sitting just behind it — an edge of anger that was a vital part of all he did. It’s not hard to find reasons for that suppressed rage in a broken home, poverty and racial abuse, but much of it, according to the man himself, came from growing up in the suburbs. “You’re a nothing, you’re a zero in the suburbs. You’re mundane, you’re common,” he said in that 1987 interview. The dissatisfaction seeps out in all his best songs, and it’s his secret ingredient, the edge that makes the sweet, catchy tunes so resonant. It’s in the contempt for his bar-room characters in Piano Man, in the put-downs of Big Shot and the “leave me alone” of My Life, even in the underdog chippiness of It’s Still Rock and Roll to Me and Uptown Girl.

It’s seeped out in other ways, too. In 1970 he had a spell in a mental hospital after a suicide attempt, either with pills or drinking furniture polish, depending on whom he’s talking to. He likes to laugh it off as career doldrums, but then he also blames his problem drinking in the 2000s on 9/11, and three car crashes around the same time on issues in his marriage. There were two attempts at rehab for alcoholism, in 2002 and 2005, then an intervention by friends in 2009. He fell out with long-time touring partner Elton John after his fellow piano man spoke in public about Joel’s drinking.

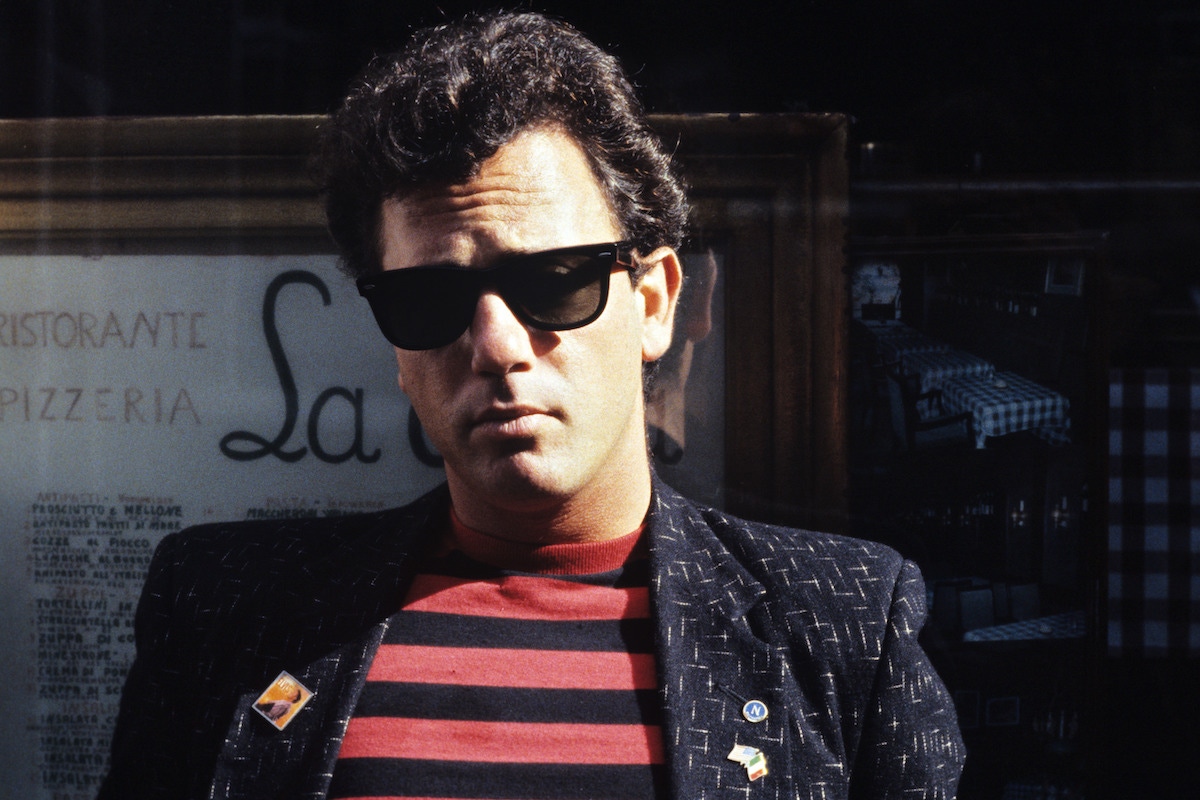

Apart from an incident in Moscow in 1987, filmed for a documentary, where he reacted to a lack of control by upending his piano and smashing his microphone stand repeatedly on the stage — while, ever the professional, continuing to hit his lines — Joel has kept any outbursts in private. It’s possible the rage became the drive for his career, because he seems to lack the usual ego and ambition that underpins a star of his level. He’s always painted himself as just another guy from the suburbs, an entertainer rather than a star, an ordinary man with an extraordinary talent, so much so he may even believe it. This despite the fact that, on paper, he’s been through almost every one of the rock-star rites of passage.

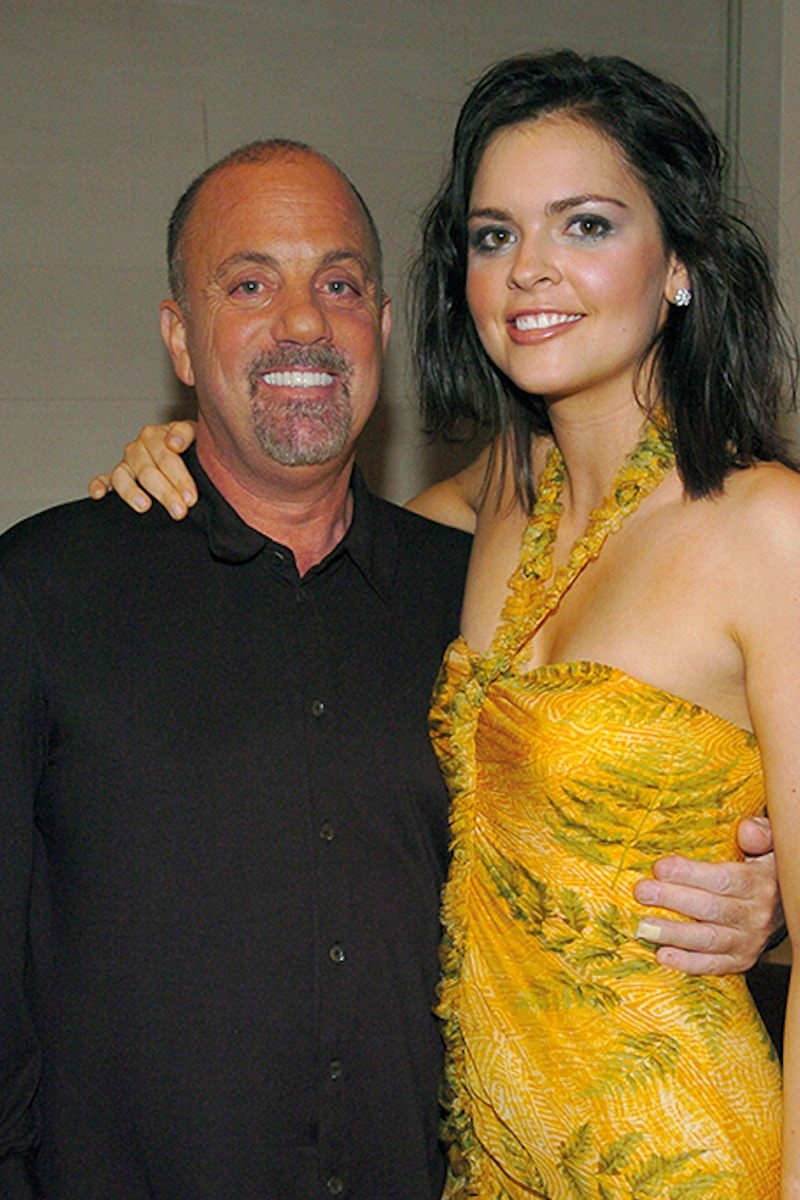

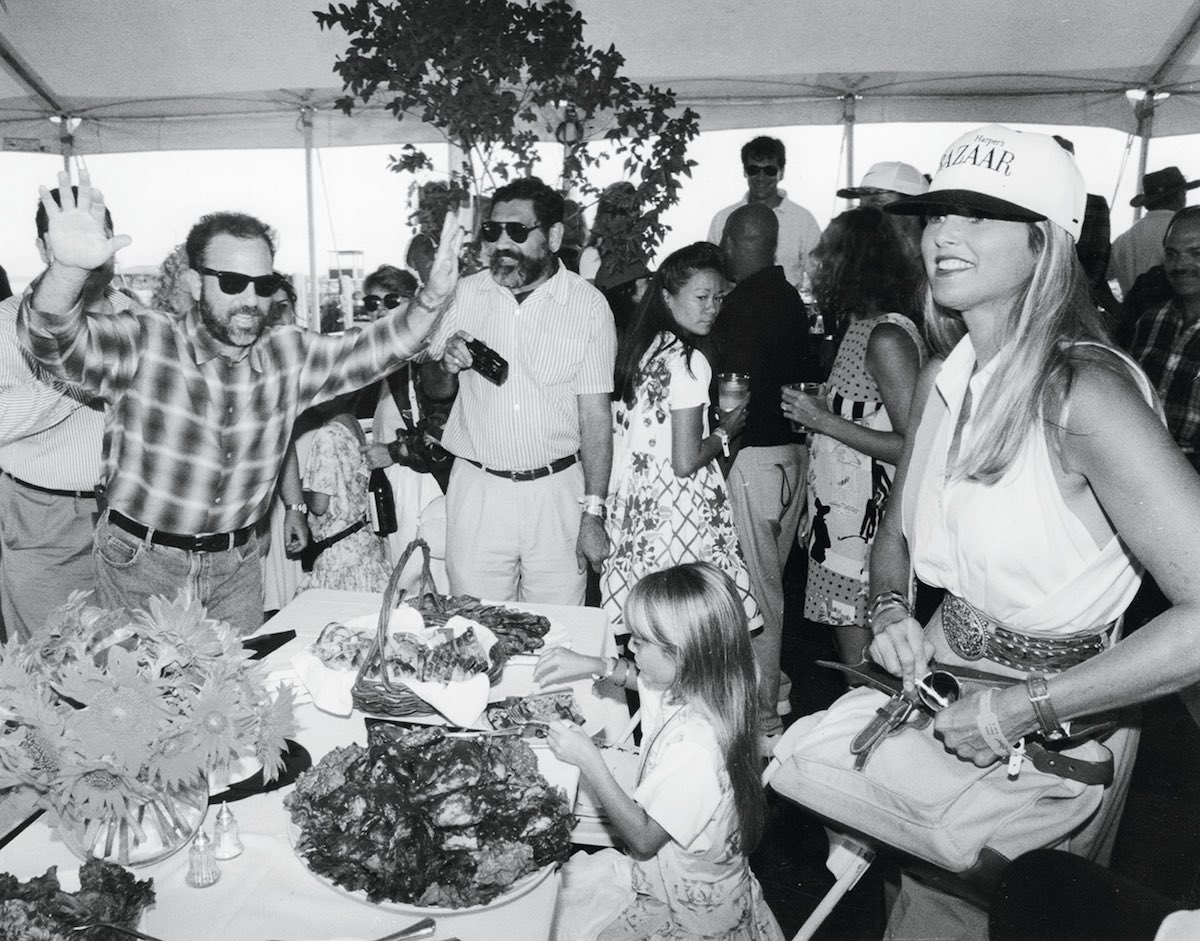

Most famously, there was his marriage to Christie Brinkley, possibly the most famous model in the world, and that line about “giving hope to every ugly guy in the world”. It’s true that he’s small, pop-eyed and broken-nosed: in his words, “I look like the guy who makes pizza”. Brinkley called him Joe, because that’s how he looked to her, but he was still a Joe she met around a piano on St. Barts, with Elle Macpherson (whom he dated first) and Whitney Houston. He’d already been married, to Elizabeth, variously the wife of Attila’s drummer, the waitress mentioned in Piano Man, the subject of She’s Always a Woman, and his manager. After Brinkley, he married the television food presenter Katie Lee, 23 to his then 55, and since 2009 he’s been with the former financier Alexis Roderick. He’s always denied being a ‘jet-setter’ but his version of staying close to his roots is a series of ever-increasing mansions in Long Island’s rather un-suburban neighbourhoods, overlooking Oyster Bay or in East Hampton or Martha’s Vineyard. His passions beyond music are working-class but on a millionaire’s scale: he loves motorbikes, so he has a garage of 100 of them, and commissions mechanics to customise them for him. He’s into boats, so he designs and builds his own, including a 57-foot powerboat.

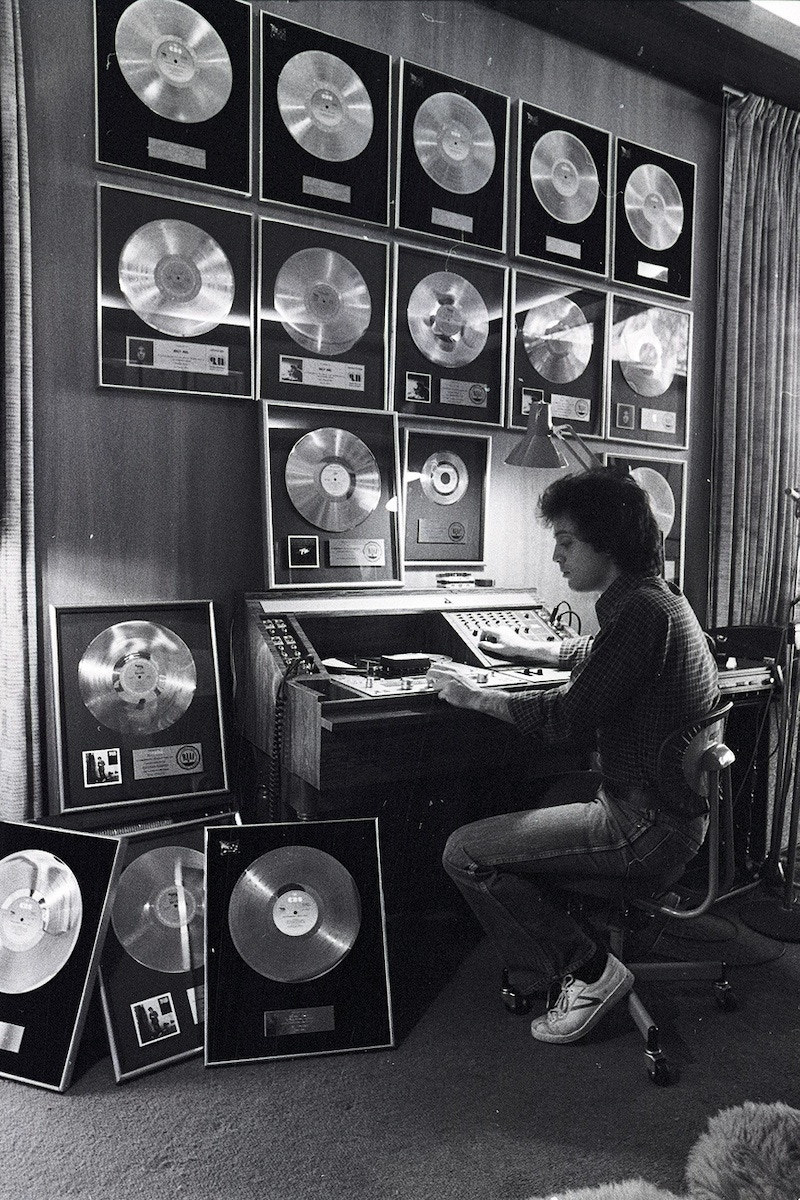

It’s the kind of indulgence that looks silly on paper, but then Joel has made a vast amount of money from his music over five decades. Admittedly, it should have been much more — he signed a typically punitive contract for his first album and spent much of the eighties retrieving royalties embezzled by lawyers and managers, including his former brother-in-law — but as it stands he’s up there with pop’s biggest all-time earners. All this is without releasing a pop record since 1993’s River of Dreams (he’s pretty outspoken on his contemporaries spoiling their legacy with substandard releases) and restricting composition to purely classical pieces. In the meantime, he plays the hits to stadiums of adoring baby boomers, racking up a run of residencies at Madison Square Garden, a convenient helicopter hop from home.

It’s a happy career autumn, but then time has been kind to almost all musicians of Joel’s generation, for whom the money and the reverence increase every year. He always said it was the songs that were important, not (to paraphrase the spleen-venting It’s Still Rock and Roll to Me) the clothes that he was wearing, and it turns out he was right. His perspective on his own legacy is measured: he doesn’t like playing Just the Way You Are, for example, and when talked into it he’s prone to undercut it with a line like “And then we got divorced” — the hoodlum’s fist inside the elegant white glove again. But for anyone over 50, even that song has lost its old-people-music fustiness, long ago become just another pretty memory, like Hey Jude or Tiny Dancer, further evidence of Noël Coward’s potency of cheap music. Perhaps Billy Joel’s great secret is that he never fooled himself that it was any more than that in the first place.

This article originally appeared in Issue 68 of The Rake.