WHEN MICHAEL AND TINA RULED THE WORLD

It was where Andy Warhol held court and John Lennon enjoyed his last supper. Bowie, Basquiat and Madonna were regulars. Originally published in Issue 53 of The Rake, Stuart Husband writes that in 1980s New York, the restaurant Mr Chow was where the glitterati went for a bite to eat. And the husband and wife behind it were Michael and Tina Chow, whose rise and fall through international society played like a Chinese opera…

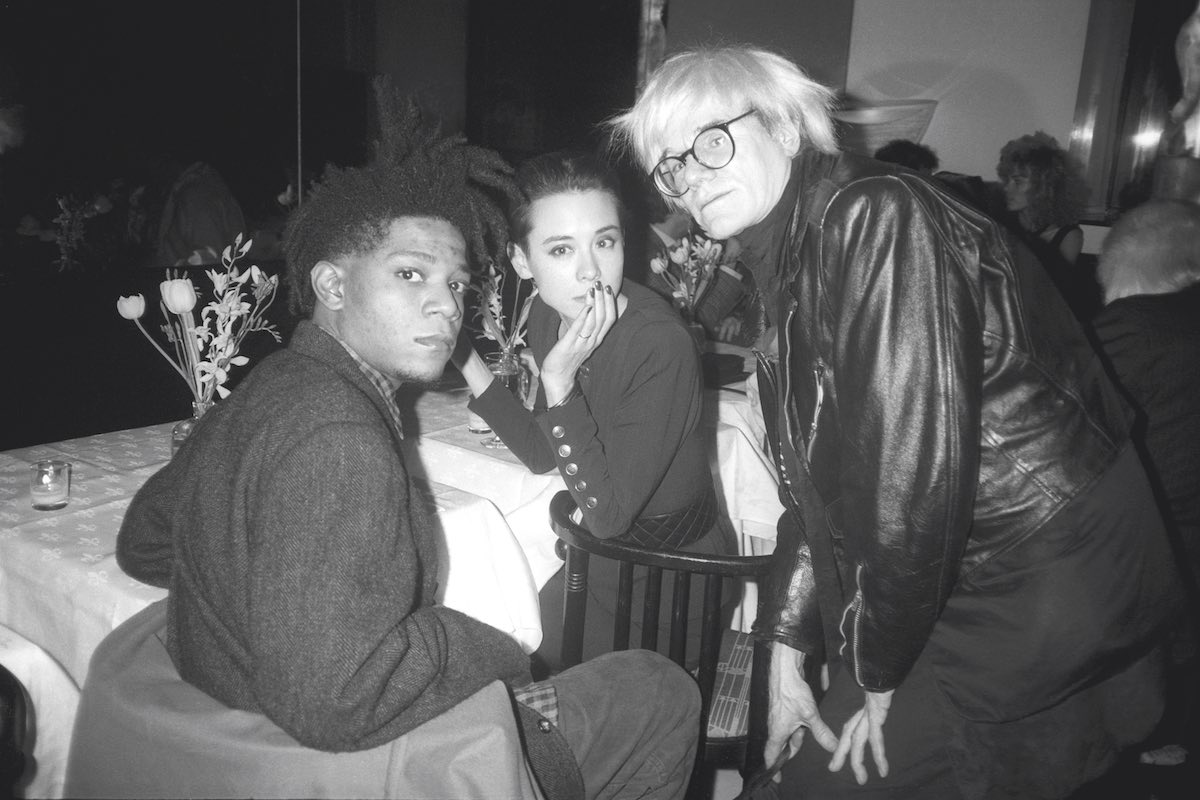

One evening, sometime in the mid eighties, the film producer and director Brett Ratner went to New York City’s Midtown for a Chinese meal. “I’m sitting there, and right next to me you’ve got David Bowie,” he recalled. “Sitting across from me is Jean-Michel Basquiat, Andy Warhol, Keith Haring, Madonna, too, and Francesco Clemente. This place instantly became my favourite restaurant in the whole entire world.”

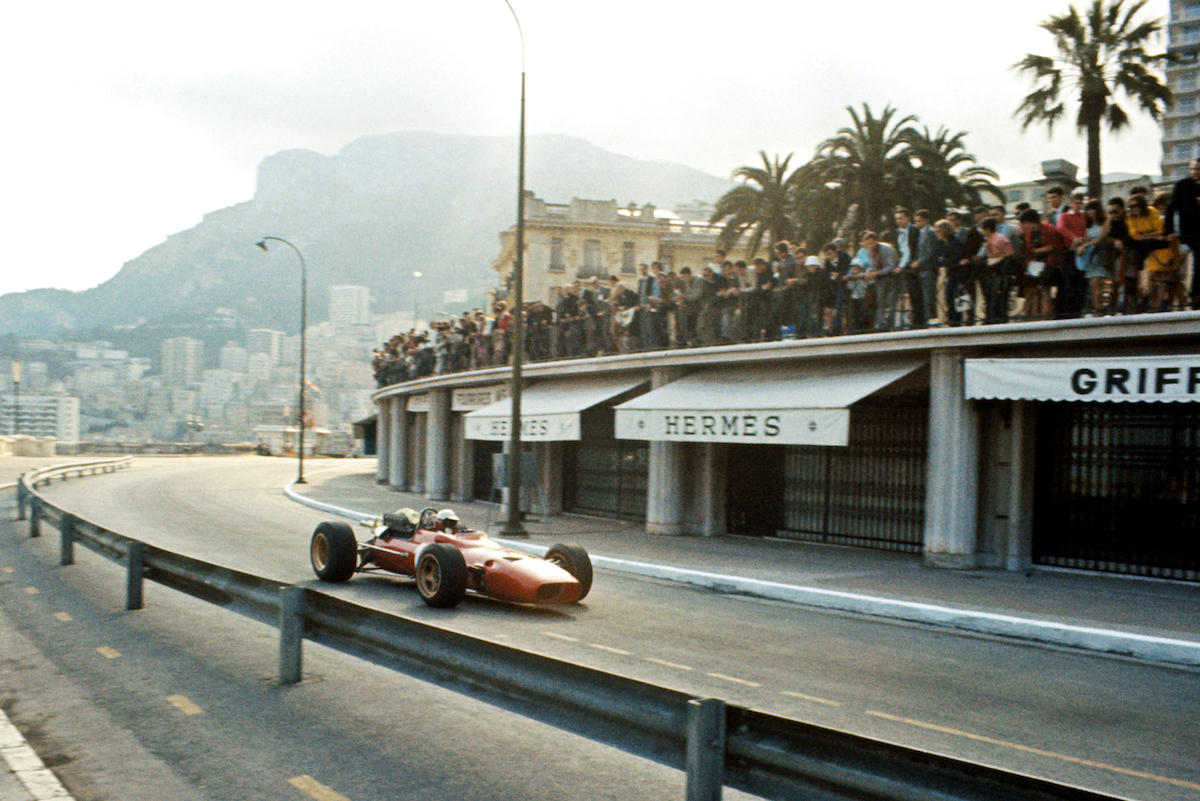

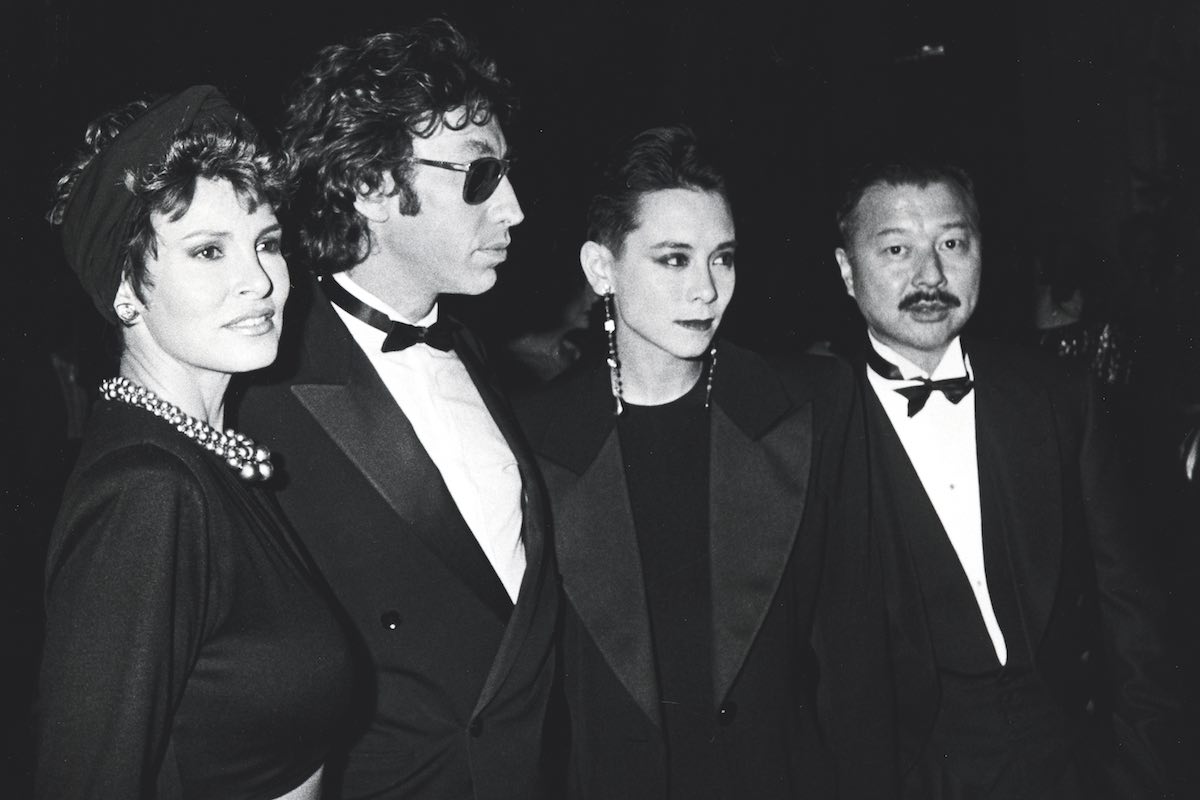

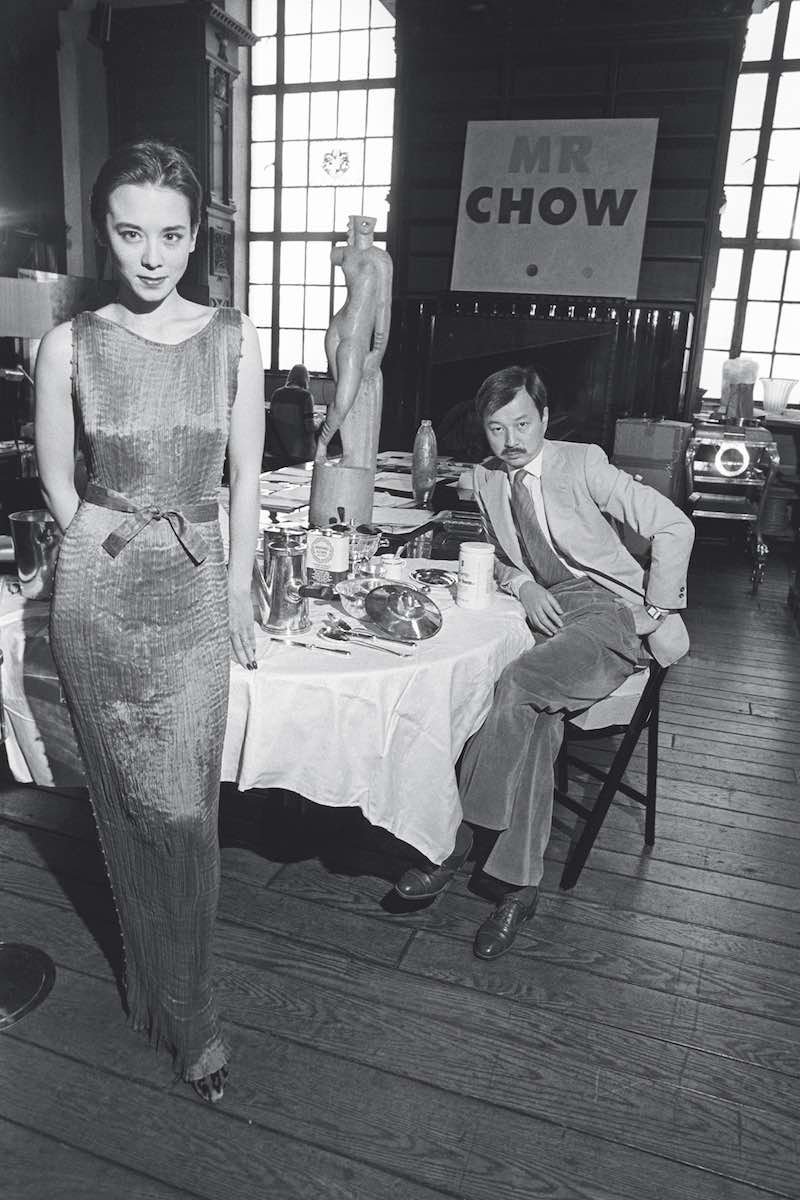

By now, you’ve probably twigged that Ratner hadn’t popped into the Golden Dragon Buffet or the Old Sichuan. He’d opted for a place where the melange of celebrities was as piquant as the chicken satay or the green prawns: Mr Chow. Presiding over the revels — Julian Schnabel’s 40th birthday party, say, or Warhol’s 58th — were the restaurant’s charismatic hosts. Michael Chow, Shanghai-born and Europe-schooled, would be acting as beetle-browed ringmaster, immaculate in his bespoke Hermès suit, keeping a beady eye (encased in his trademark chunky-framed, starchitect-style round glasses) on his Armani-clad Italian waiters as they filled flutes, changed tablecloths, or painstakingly deboned rare, fresh pieces of fish. His wife, Tina, half-American, half-Japanese, whose gamine beauty saw her serving as model and muse to the likes of Helmut Newton and Cecil Beaton, would be sharing fashion- or art-world gossip with friends like Herb Ritts and Karl Lagerfeld. Like Studio 54 in the previous decade, it seemed that this 57th Street establishment had captured the super-heated New York zeitgeist. It was the place where Warhol held court at a long table, several times a week, “not eating”, said Michael, “just pushing his food around”; it was the place where John Lennon ate what turned out to be his last supper. “Every city has a time,” Michael told New York magazine, when attempting to account for his restaurant’s folkloric stature. “The twenties was Berlin, the thirties was Paris and Shanghai. And then in the fifties, everything is Rome. And then in the sixties, it’s London. Then the seventies in L.A., and then eighties art-world New York. We are always in the happening city.”

True, but Mr Chow’s New York outpost — the restaurant’s third iteration — was widely regarded as the couple’s masterpiece. It opened in 1979; the interior, as in all his restaurants, was designed by Michael, who’d studied both art and architecture. It was a white glass-lacquered space with a bronze standing lamp by Giacometti, double glass doors by Lalique, a soaring ceiling sculpture by Richard Smith, white marble floors, alabaster and bronze fan-shaped sculptures by Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann, ice buckets from the SS Normandie, padded tables lit from below and surrounded by Josef Hoffman chairs, and specially commissioned 28-inch-square napkins, which, according to Tina, were “like blankets”. The Chows lived above the shop, in a duplex with a neo-Gothic Louis Comfort Tiffany interior described by Michael Walsh, a vintage fashion dealer and friend of Tina’s, as “a satanic mess, dark and amber, like Citizen Kane”. In the early eighties, the apartment was transformed into a white silk-walled showplace for Michael’s extensive collection of art deco furniture — by Ruhlmann, Eileen Gray, and Jean Dunand – which, according to Walsh, was “like the set of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis”.

It was Michael’s punctilious eye for set-dressing that transformed Mr Chow’s from a mere eatery into a kind of gastronomic theatre. It was, he averred, just like constructing one of his Hermès suits: “Everything is based on a universe of subliminal details. When you pull it together, there is content and quality. Every stitch is a universe, and has its own high standard.” And if his more celebrated patrons sometimes had a less-than-reverential attitude to their surroundings — “It was like a car crash, growing up there,” recalled a not-at-all contrite-sounding Schnabel. “I remember feeling sometimes like we’d been at someone’s parents’ house and we’d wrecked the place” — there was always the emollient presence of Tina to soothe savage breasts, of alpha-dog artists and highly strung husbands alike. “Michael was refined by Tina,” said her friend Nadia Ghaleb, who managed Mr Chow’s Beverley Hills branch. “She balanced Michael’s energy with her grace, simplicity and kindness. They were complementary opposites.”

Michael came from aristocratic but forward-thinking stock: his father, Zhou Enfang, was China’s most famous actor, the eminence of the Peking Opera in Shanghai. His mother came from a wealthy dynasty who’d made their fortune in tea, although, as Michael was fond of hinting, opium may also have been involved. His parents eloped together — Zhou was already married, with three daughters — which sent shockwaves through thirties Chinese society, though Michael, born in 1939, was more alert to “a splendid childhood of cars and servants” rather than any prurient interest in the family’s soap-opera-style dynamics. Which must have made it all the harsher when, at 13 and fluent only in Mandarin, he was dispatched to Wenlock Edge, a boarding school in Shropshire that seemed determined to live down to all the clichés of post-war, unenlightened, austerity Britain: incessant canings, a single leg of lamb shared among a hundred boys. “It was like Harry Potter, but without the magic,” he recalled. “Lonesome is not even the word.”

Michael reacted by exploiting his otherness and becoming a ‘character’, starting with his bottle-brush moustache and statement eyewear. “I call them my ‘anti-racism glasses’, because people look at the glasses more than me, so the Chinese part begins to disappear,” he said. When he arrived on the scene in sixties London, fresh out of Central Saint Martins art college, he found a receptive environment for his studied idiosyncrasies. “It was a very interesting time,” he said. “Class and race didn’t matter so much. If you are eccentric and artistic and princely, they accept you then. This was the real cultural revolution, and I was part of that.”

He worked at the Fraser Gallery, fiefdom of Robert ‘Groovy Bob’ Fraser, one of Swinging London’s chief rabble-rousers, hanging out with the gallery’s stars — Jim Dine, Peter Blake, Richard Smith — and throwing himself into the capital’s giddy ferment. There was a brace of marriages — one a six-day wonder, and one to Grace Coddington, then a flame-haired model, latterly the Creative Director of Vogue. He opened a hair salon, only to sell it to Twiggy. He opened a boutique and a nightclub. He tried his hand at acting, appearing in minor roles in Modesty Blaise and You Only Live Twice. He tore round town in a Bentley convertible dressed in purple silk Nehru suits by Yves Saint Laurent, his shoulder-length hair flying in the wind. “He was a wild man,” enthused Nadia Ghaleb, “the hippest, hottest, coolest guy in London.” And then, in 1968, he opened Mr Chow in a former curry house in Knightsbridge.

Prior to Mr Chow, Chinese restaurants tended to be tacky, pile-it-high-sell-it-cheap, MSG-laden places stuffed with ersatz chinoiserie; Michael gave his a western sheen (white tablecloths, forks instead of chopsticks), reassuringly high price points, an OCD-like attention to detail (the Mr Chow rulebook includes a section on the perfect, three-fingered way the waiters should place the plates on the table), and an ambience that was more happening than hackneyed. Art by the Fraser Gallery alumni was hung on the walls, simple but seductive food was served, from velvet chicken to sweet and sour pork, and Michael’s glamorous friends came to eat, drink, and — more importantly — hang out. The Beatles made Mr Chow their works canteen; Paul McCartney was spied there one lunchtime, working out the chord progression for a new tune called Back in the USSR. Federico Fellini, Frank Sinatra and Jeanne Moreau were all regulars. It became the after-hours after-party venue for every gallery opening and movie premiere. It seemed that the buzz around the place couldn’t get any more intense. But then, in 1971, while touring a Buddhist temple in Kyoto, Michael met Bettina Lutz.

Tina’s striking Eurasian looks — her G.I. father met her mother during the Japanese occupation — had the power to stop traffic; during a trip to China in 1985 with Michael, cyclists collided with each other as she strolled serenely by, oblivious. Born in Ohio but raised in Tokyo, her style was a cool, collected east-meets-west mix — she started modelling for Shiseido and Issey Miyake while still in her teens — with an androgynous twist; her favourite outfit was a white T-shirt, a man’s cardigan, and a pair of Kenzo jodhpurs she had copied and re-copied for years. “She invented minimal chic,” Lagerfeld said, “and no one looked better in it than her.”

Michael and Tina were introduced to each other by their mutual friend, the fashion designer Zandra Rhodes. “She was a match that lights things and helps them burn brighter,” Rhodes said of Tina, “an attractive, intelligent instigator.” The Chows were married in 1972 at Chelsea registry office, followed by lunch at — where else? — Mr Chow. “We were all crazy-drunk, dancing on tables,” recalled Juan Ramos, an art director friend of Tina’s. Manolo Blahnik acted as an unofficial wedding photographer, and a nine-year-old Tatum O’Neal arrived with Bianca Jagger at 4pm, carrying matching canes. The party moved on to Michael’s nightclub, Maunkberry’s. “Then they began the life of a perfect couple,” said Ramos.

If there was some caustic irony in that statement, it was because the couple’s circle had already detected a Pygmalion complex in Michael, who was 12 years Tina’s senior. “I’m sort of the teacher type,” he said. “I was into fashion, into artists. So the background was set for her.” As a couple they were formidable, the centre of every party, most notably at Mr Chow Beverley Hills, which opened on North Camden Drive in 1973. Clint Eastwood and Eartha Kitt came to the launch; Billy Wilder, Anjelica Houston and her then-boyfriend, Jack Nicholson, became regulars; Barbra Streisand was introduced to James Brolin at one of Mr Chow’s tables. Mae West was given a standing ovation for polishing off her noodles and scrawling “for food that’s best, ask Mae West” in the visitors’ book. Michael even remained sanguine when Groucho Marx turned up, only to have a hamburger delivered to his table from a rival establishment after 30 minutes of stonewalling the waiters. “If they’re artists, they can do whatever they want,” he shrugged.

This was also the rule of thumb at Mr Chow New York: not only were art-scene luminaries drawn to Tina’s brand of downtown chic — she’s mentioned in Warhol’s Diaries 11 times to Michael’s twice — but they also benefited from Michael’s long-standing practice of trading art for food. A celebrated New York Times Magazine profile of Jean-Michel Basquiat, from 1985, opens with him ambling into Mr Chow, where “the waiters all greet him as a favourite regular”. He sits at a table with Keith Haring, while Warhol chats on the other side to Duran Duran’s Nick Rhodes: “Over Mr Chow’s plates of steaming black mushrooms and abalone, Basquiat drank a kir royale and swapped stories with Haring about their early days on the New York art scene.” “It was a little overwhelming,” recalled their contemporary Kenny Scharf of the feeding frenzy. “I wasn’t used to high-class restaurants as hangouts. I’d never had Cristal, which flowed in that eighties indulgence kind of way.”

The Chows had two children — a daughter, China, and a son, Maximilian (who’s now head of culinary operations at the Mr Chow empire) — but, just as they reached their professional apotheosis, with the restaurants grossing around $2 million each a year, the fissures in the marriage became apparent — strikingly so in a 1984 Helmut Newton photograph of the pair at the bar of Mr Chow New York. Tina is bound to the rail with rope, her eyes downcast, while an impassive Michael looks on, highball in hand. During the same trip to China in which Tina had a deleterious effect on cycle traffic, Michael, who’d had no contact with his family behind the ‘bamboo curtain’ since leaving for England, discovered that his parents had been purged during the Cultural Revolution and had later died. Back in New York, he fell into a depression, installing a closed-circuit T.V. in the restaurant and watching an increasingly agitated Tina play host from upstairs. Warhol urged her to find a new creative outlet. “Michael wanted to keep her locked in a white lacquer box, like a puppet, while she wanted to get away from his craziness,” said Juan Ramos. “It’s a tragic story of people climbing the ladder of international society, and then it all falls apart. It would make a great Chinese opera.”

Michael and Tina’s marriage finally burst at the end of the eighties, along with the New York art bubble. Tina went on to design jewellery, embrace Buddhism and vegetarianism, have an affair with Richard Gere, and, tragically, become the first prominent heterosexual woman to contract HIV and die of AIDS, in 1992, following a further affair with a bisexual French aristocrat. Michael remarried — his fourth wife, Eva Chun, is a Korean fashion designer — and, as he approaches his ninth decade, he’s become an art-world eminence in his own right, sitting on the board of L.A.’s Broad Museum as well as showing his own expressionistic canvases in galleries around the world. Mr Chow rolls on, now as much of an entrenched brand as the Hard Rock Café or Trader Vic’s, with J-Lo and P-Diddy rubbing shoulders with the ghosts of Basquiat and Warhol. If it’s not the epicentre of cool any more, as it was in Michael and Tina’s heyday, it’s still a prime influence on any gastro-dramaturgical establishment that sets as much store by ostentation as consumption. “Every night at Mr Chow’s was like your fantasy dinner party,” Brett Ratner said, “the one that goes on all night and that absolutely no one wants to leave.”

This article originally appeared in Issue 53 of The Rake.