Pamela Harriman: Of Vice and Men

Could the man after whom this magazine was named have a female equivalent? Originally published in Issue 40 of The Rake, Stuart Husband writes that Pamela Harriman, a woman of aristocratic stock, blazed a trail through the international scene of her era, enticing powerful men like moths to a particularly feisty flame.

There aren’t many people whose lives have such an epic, eventful sweep that they seem to combine the rumbustious picaresque of the 18th-century novel and the slightly more salacious demands of its late 20th-century equivalent. But Pamela Harriman’s was one such life. She was born in England in 1920, into an old aristocratic milieu that the likes of Samuel Richardson (the author of Pamela, lest we forget) may still have just about recognised; by the end of her life, 77 years later, she was an Hon. of a different stripe, a U.S. ambassador to France with three marriages and innumerable affairs with powerful men behind her, and a starring role in Truman Capote’s Answered Prayers, his unfinished tell-all swansong in which he gleefully stripped bare the lives of all his barely disguised socialite friends (not so much a roman à clef as a roman à trousseau de clefs).

In the novel, Lady Ina Coolbirth (a.k.a. Harriman) takes Jonesy (a.k.a. Capote) to lunch at La Cote Basque, where she swigs Cristal and holds forth on various (undisguised) Alpha women, from Princess Margaret (“she’s such a drone”) to Jackie Kennedy and sister Lee Radziwill: “They’re perfect with men,” she says, “a pair of Western geisha girls. They know how to keep a man’s secrets and how to make him feel important.” Capote’s eyebrow was arched to breaking point here, as Lady Coolbirth’s coolly admiring assessment of the sisters was the generally accepted view of Harriman herself; one of her lovers, Baron Elie de Rothschild, called her a ‘European Geisha’, and she was referred to more than once as The Last Courtesan.

She was born Pamela Digby into a gilded but straitened life in Dorset. Her father was the 11th Baron Digby and her mother was the daughter of the 2nd Baron Aberdare. Money was tight — she was able to make her ‘debut’ only after her father placed a lucky bet on the Grand National — and her horizons seemingly tighter. “I was born in a world where a woman was totally controlled by men,” she once said. “The boys were allowed to go off to school. The girls were kept home, educated by governesses. That was the way things were.”

But the young Pamela already sensed a means of transcending the hunt ball set. At 12 she was reputed to have jumped her horse over the tumescent phallus of the Cerne Abbas giant, an ancient figure carved into the chalk hills near the family home of Minterne, exclaiming: “God, it’s big!” She also became fascinated by the story of her ancestor Jane Digby, whose amorous adventures (while married to the much older Lord Ellenborough; she had an affair and two children with Prince Schwarzenburg of Austria, became the mistress of King Ludwig of Bavaria, and eventually married a Syrian sheikh on condition that he gave up his harem) titillated Victorian London. After finishing school (France, Germany) she began to hone her talents as a siren, understanding that the only way for women to achieve any clout was through captivating and influencing those with real power. Not everyone was convinced — she had “kitten eyes full of innocent fun”, in Evelyn Waugh’s equivocal words (he gave her the disdainful nickname ‘Panto’), while Nancy Mitford regarded her as “a red-headed bouncing little thing, and a joke among her contemporaries”. Yet she deployed every weapon in her armoury, from her champagne voice to her peerless managerial skills and gracious hostessing, to snare her quarry. “She might have been beautiful if she hadn’t had such a short neck, but that’s because her head’s screwed on so tight,” was one grudgingly appreciative comment. “If you put a blindfold on her in a crowded room, she could smell out the powerful man,” was another.

At 19 Pamela went on a blind date with Winston Churchill’s only son, Randolph, who exhibited a typical brilliant-father’s-shadow cocktail of arrogance, extravagance and drunkenness. He proposed at the end of dinner, having been previously spurned by a number of other women (including, legend had it, three in one night). He was heading off to war and, convinced he would die, urgently required an heir; it was not the surest footing on which to base a marriage, but Pamela accepted. They had a son, named Winston, reflecting Pamela’s warm relationship with her father-in-law. She called him Papa and shared his Good War by bringing him the London gossip, moving into 10 Downing Street when he became Prime Minister, playing small-hours hands of bezique with him during his frequent bouts of insomnia, and attending dinner dances at Chequer’s, Claridge’s and The Dorchester, where Lord Beaverbrook became her mentor, Franklin Roosevelt’s envoy Harry Hopkins became her friend, and W. Averell Harriman, the Democrat politician, businessman and diplomat, became her lover.

Harriman was already married (though his wife was safely back in the U.S.) and he was 49 to Pamela’s 20, but she exalted him as the best-looking man she’d ever seen. With Harriman underwriting her expenses, she left her son with her in-laws and took up residence in Grosvenor Square, then filled with American expats, and dubbed it Eisenhowerplatz. She demonstrated her Blitz spirit by conducting parallel affairs with her neighbour John Hay (Jock) Whitney, later the U.S. ambassador to Britain, and revered CBS broadcaster Edward R. Murrow, who was reporting on the war from London. By the end of hostilities, her star had risen so dizzily that William Walton could claim that “Pamela was the only person in London to receive three separate letters from three separate participants at Yalta”.

No wonder she found it hard to adjust to peace. Churchill was out of government; her connection to the family was severed with divorce from Randolph in 1946; Harriman had become ambassador to Moscow; and London, despite the victory, felt as restrictive as her Dorset girlhood. Luckily, Beaverbrook installed her as the Paris correspondent for his Daily Express, and she crossed the Channel to find a city more than keen to shake off the depredations of occupation. “Every night then was lived in black tie,” recalled a contemporary of Pamela’s. “There was less money than in New York or London today, but far more luxury; there were fewer names and far more taste.”

Pamela immediately set about getting to know some of the biggest names around. She had a fling with Prince Aly Khan, the playboy son of the Aga Khan who would go on to marry Rita Hayworth; it was allegedly during their time together that she refined the technique of arranging her features into a gaze of fervent interest when listening to male pronouncements. She then fell in love with Gianni Agnelli, style icon and heir to the Fiat empire. He established her in an apartment on the Avenue de New York, with a car and chauffeur (provoking a touchingly naïve Lord Digby, after a visit, to pronounce how clever she was to manage so adroitly on her meagre allowance).

In return, Pamela converted to Catholicism and embraced the Italianate to an extent that startled callers to her apartment, who were greeted with the words “Pronto, Pam”. Despite her efforts, however, Agnelli let it be known that marriage to a divorced woman was out of the question, and Pamela turned her attentions to Baron de Rothschild of the French banking family (she now answered the phone, “Ici, Pam”). Rothschild arranged art history and wine-making courses for her, and his comparison of her to a Geisha may have been provoked by the fact that she was conducting a simultaneous affair with the Greek shipping tycoon Stavros Niarchos.

Years later, Pamela denied that, during this period, she was simply scouting for a rich husband. “Having been married, I was saying to myself, ‘I don’t have to get married again’,” she recalled. “I was bruised. Nobody’s ever thought that I didn’t want to marry.” But now, approaching 40 and needing a change of scene — Baron de Rothschild’s furious wife, Liliane, had sideswiped her car into Pamela’s on a Paris boulevard — she moved to New York. And married.

A friend had asked her to go to the theatre with Leland Hayward, the Broadway producer of hit musicals including South Pacific and The Sound of Music, while his wife, Slim, one of the city’s premier socialites, was out of town. According to a friend, Pamela “went from knowing absolutely nothing about Broadway to being able to quote box-office grosses in about two weeks”, and Hayward was similarly smitten. “He said that she had an extraordinary attention span and wonderful lilywhite skin, and that her apartment in Paris was known for its fabulous Louis Seize furniture,” wrote Hayward’s daughter Brooke. “He talked about her incredible jewels, and said that Somerset Maugham had finally said to her, ‘Don’t you think it’s time to get married?’”

The capitulation was complete — once Slim was speedily divorced — and over the course of their 11-year marriage, Pamela showered Hayward with what one onlooker inevitably described as “Geisha-like devotion”, cooking chicken hash on a hot plate when they were out on the road and playing the perfect châtelaine at their splendid homes in New York and Westchester (an estate called Haywire). But Hayward’s three children, from his first marriage, to actress Maureen Sullivan, never took to their second stepmother, and the feud blew into the open on Hayward’s death in 1971, when he left half of his holdings to them. Pamela apparently exclaimed, of her six-figure settlement, “How could I have been married for so many years to a man who leaves me so little?” Brooke Hayward claimed that Pamela absconded with a string of pearls that Sullivan left to her. Pamela denied all knowledge, but a double strand of pearls became one of her ostentatious style trademarks.

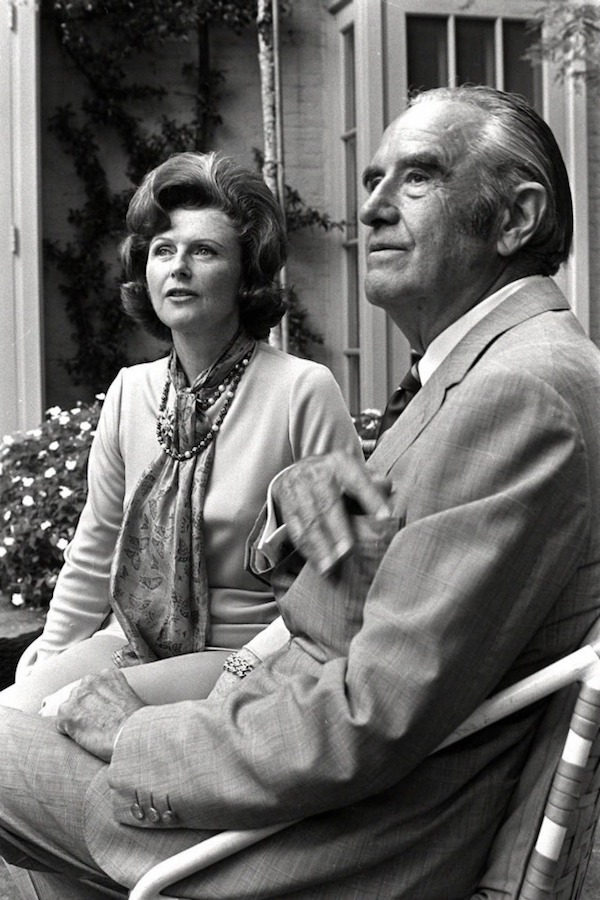

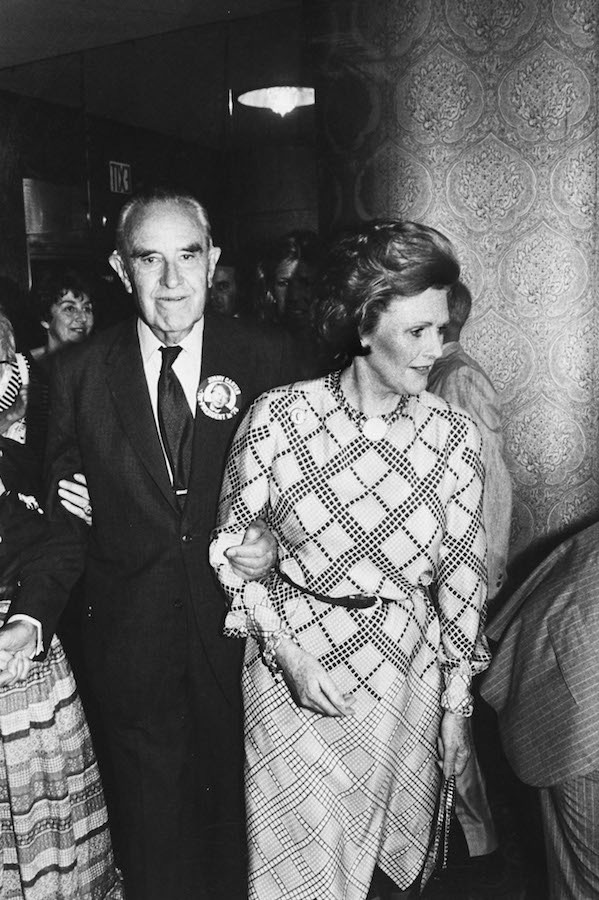

It was around this time that Pamela resumed her old acquaintance with Averell Harriman, at a party given by Katharine Graham, the publisher of The Washington Post. She heard that he’d been widowed the previous year, and wasted no time — if you discount a brief liaison with Frank Sinatra — in pursuing a renewed seduction of him. She was pushing at an open door — he had been asking people if they thought she’d like to see him again — and, while he was almost certainly the love of her life, it didn’t stop her acquiring the nickname ‘The Widow of Opportunity’. They were married six months after Hayward’s death — the bride 51, the groom 79 — and she fixed up his houses (while alienating a new set of stepchildren: “We now had to schedule appointments to see him,” one bemoaned). She became an American citizen and adopted his interests in the Soviet Union and, more exuberantly, the Democratic party, to the point where, during the Reagan years of the party’s exile, the Harrimans formed a political action committee, which became known as PamPAC, and offered their Impressionist-stuffed house in Georgetown as an informal headquarters, where she presided over numerous exquisitely appointed receptions and dinners.

There was no demurral from Pamela over the terms of Harriman’s will when he died in 1986: she acquired his $115 million fortune. And, following the little local difficulty when she was accused by Harriman’s heirs of making bad investments— she sold some property, along with a Picasso, a Matisse and a Renoir to hold off a civil suit — Pamela Digby Churchill Hayward Harriman was ready to assume her final role as Washington grand dame. She brought Bill Clinton and Al Gore together for the 1992 election, perhaps recognising a kindred spirit in ‘Slick Willie’, and was rewarded after their victory with the ambassadorship to France, where her woman-with-a-past status did nothing but enhance her standing.

She now poured her social skills into 16-hour days dealing with questions of international trade and N.A.T.O. expansion while working the transatlantic telephone lines late into the night. She died, at 76, of a cerebral haemorrhage sustained while enjoying her daily swim in the pool at the Paris Ritz. She left behind a legend: the captivating, vivacious woman who trailed a slew of starstruck men and nonplussed women in her wake. And while she once protested that she should not be held at fault if her succession of beaux happened to be rich and influential — “Those were the people I met; everything in life, I believe, is luck and timing” — she also, at the end, acknowledged the notoriety that came with her remarkable trajectory. “I’d rather have bad things written about me,” she said, “than be forgotten.” Capote surely won’t be the last wordsmith to heed the ultimate courtesan’s call.

This article originally appeared in Issue 40 of The Rake.