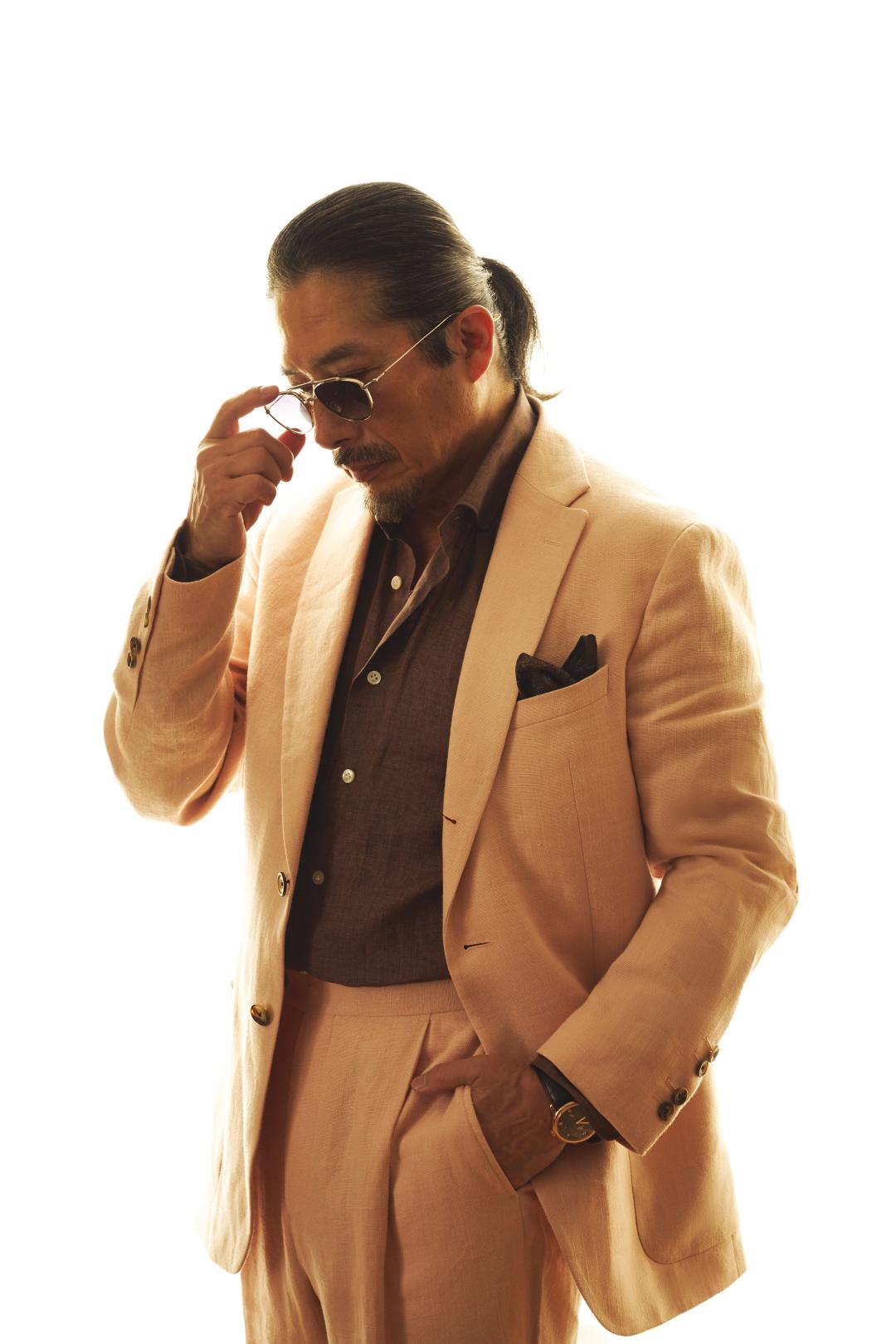

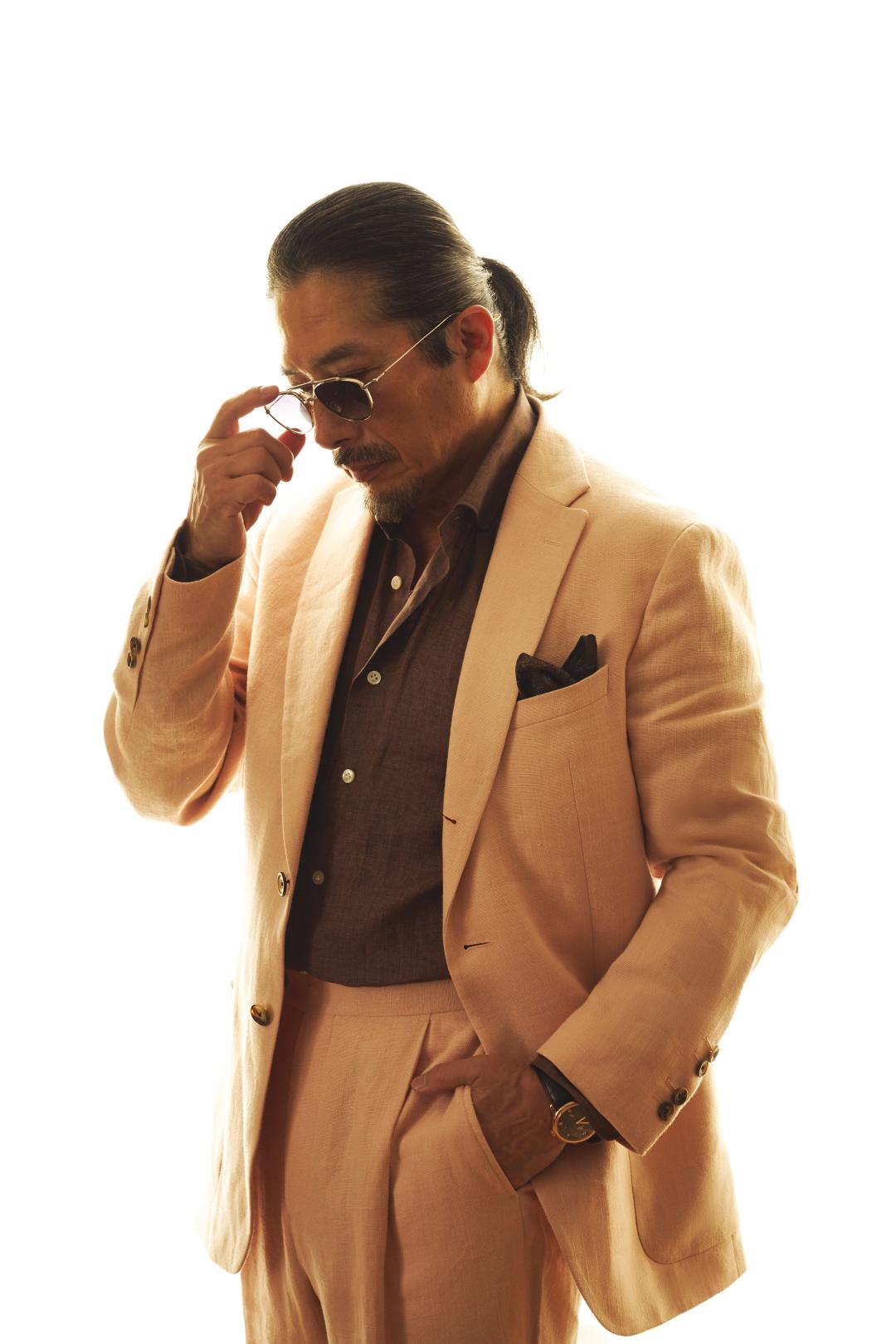

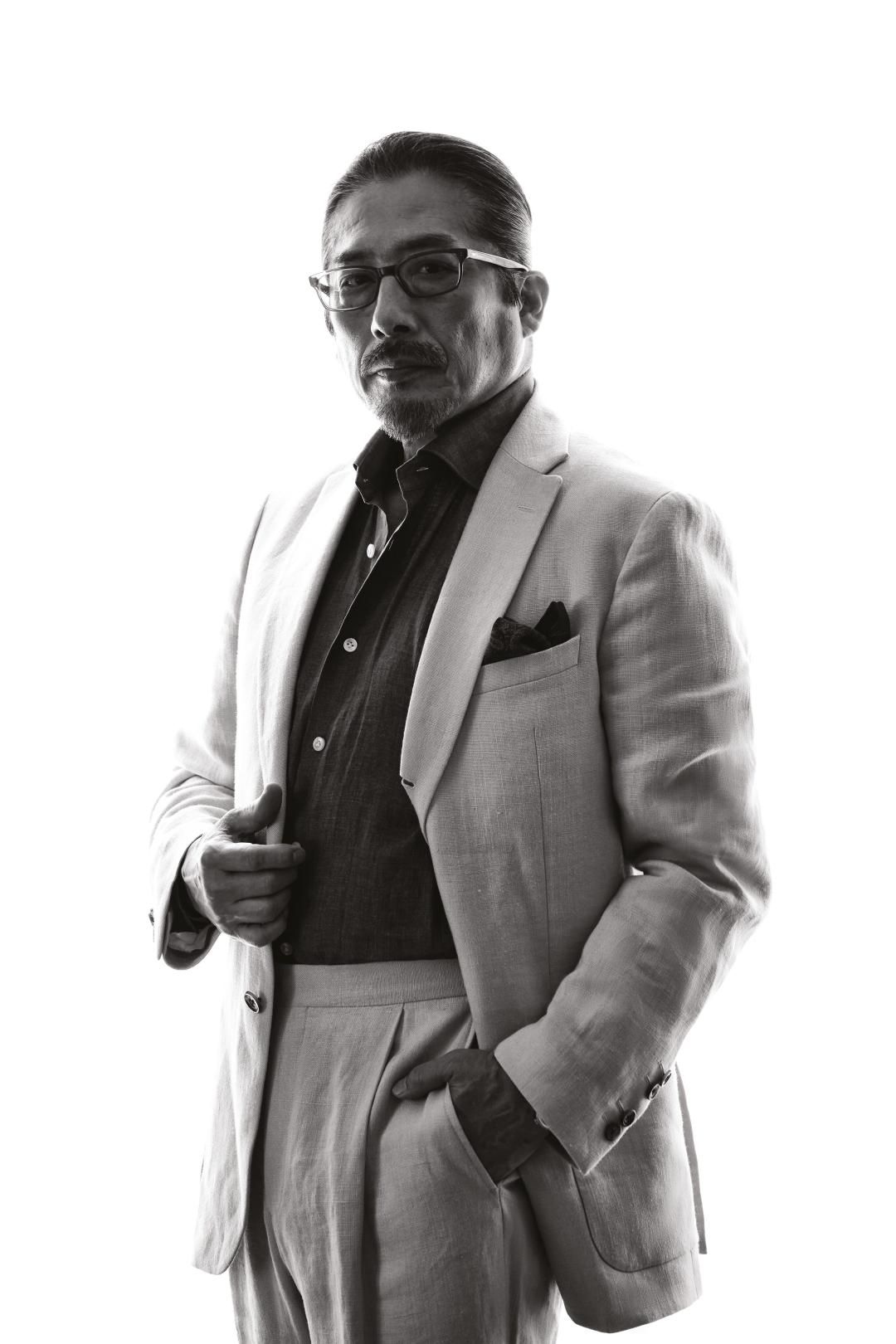

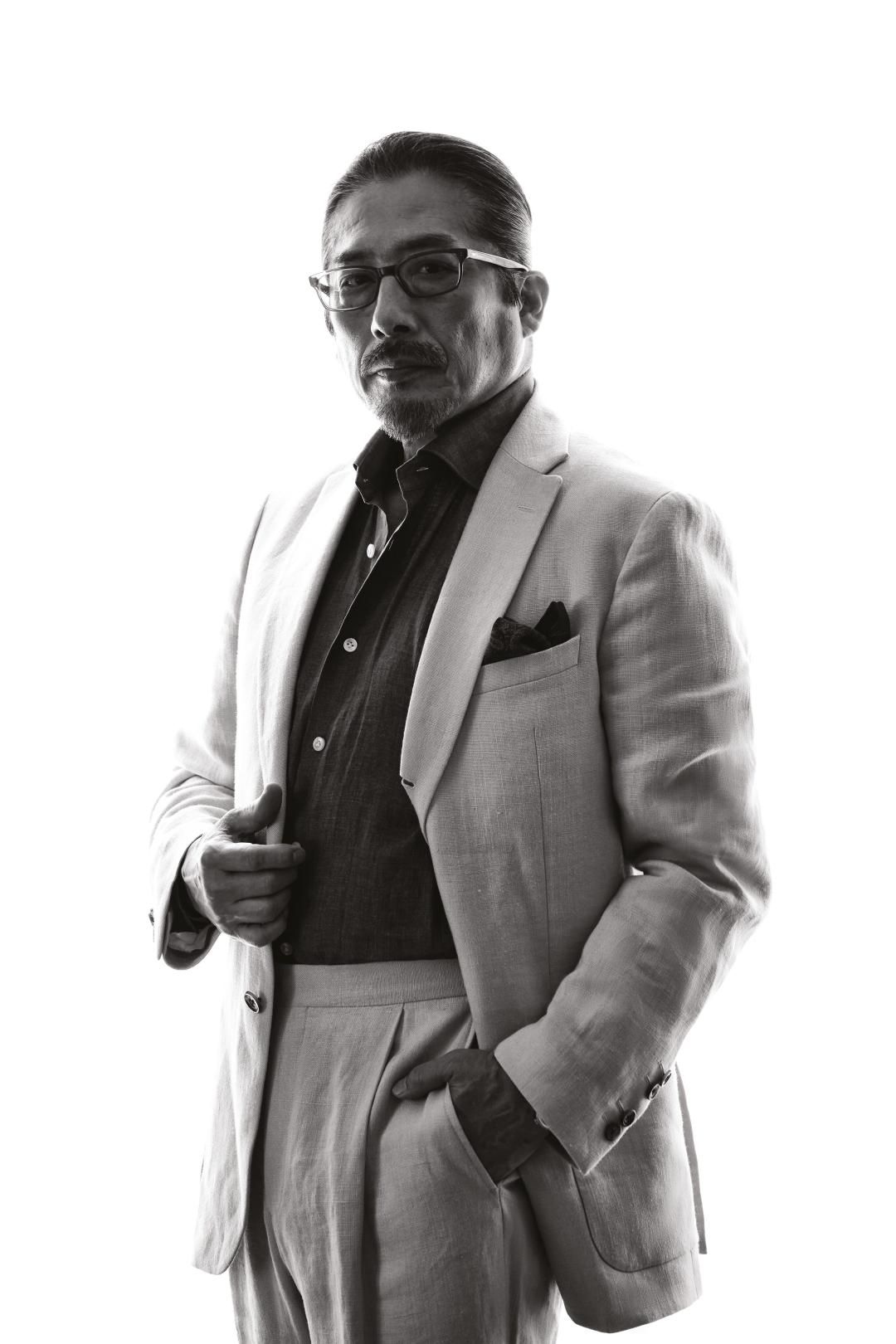

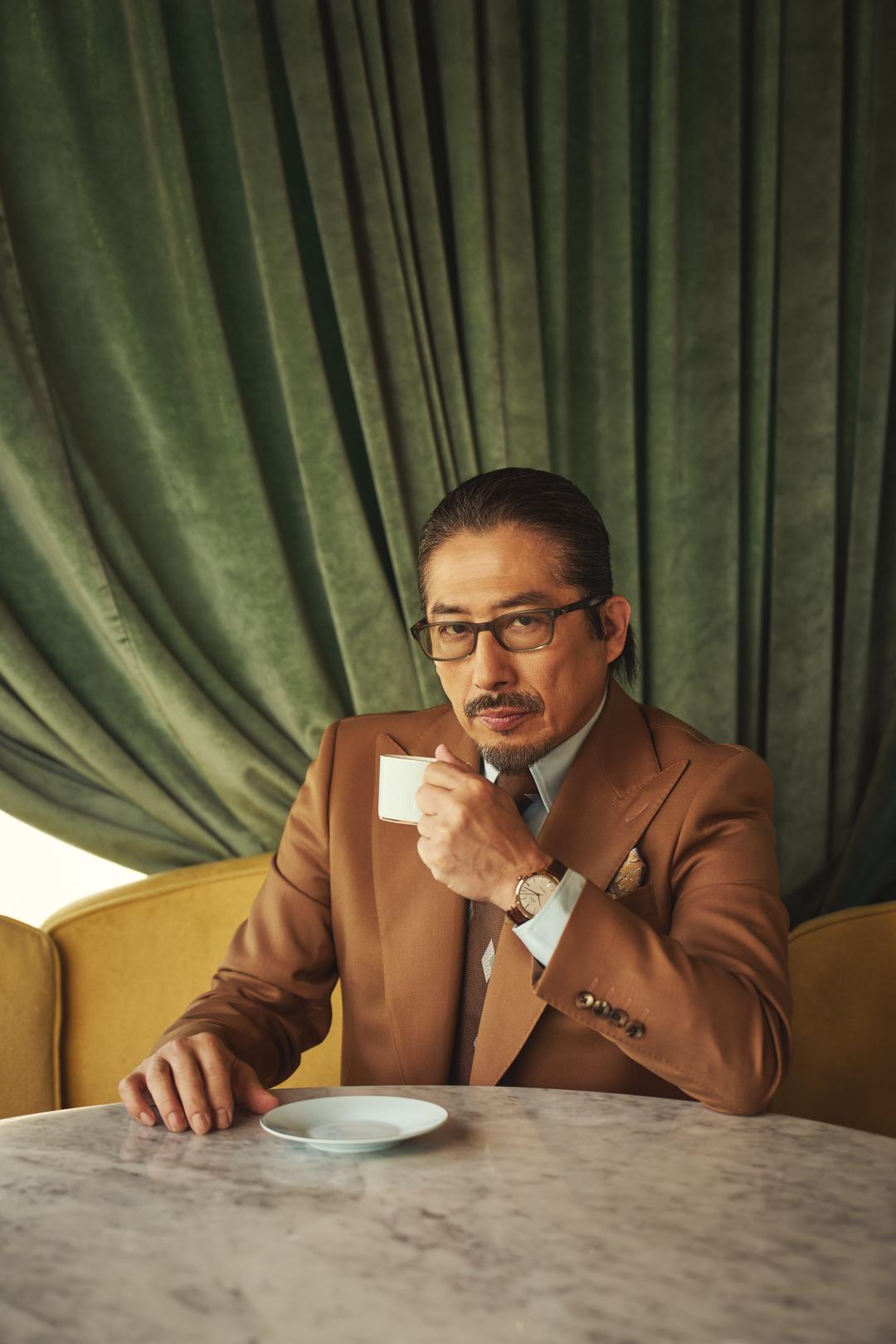

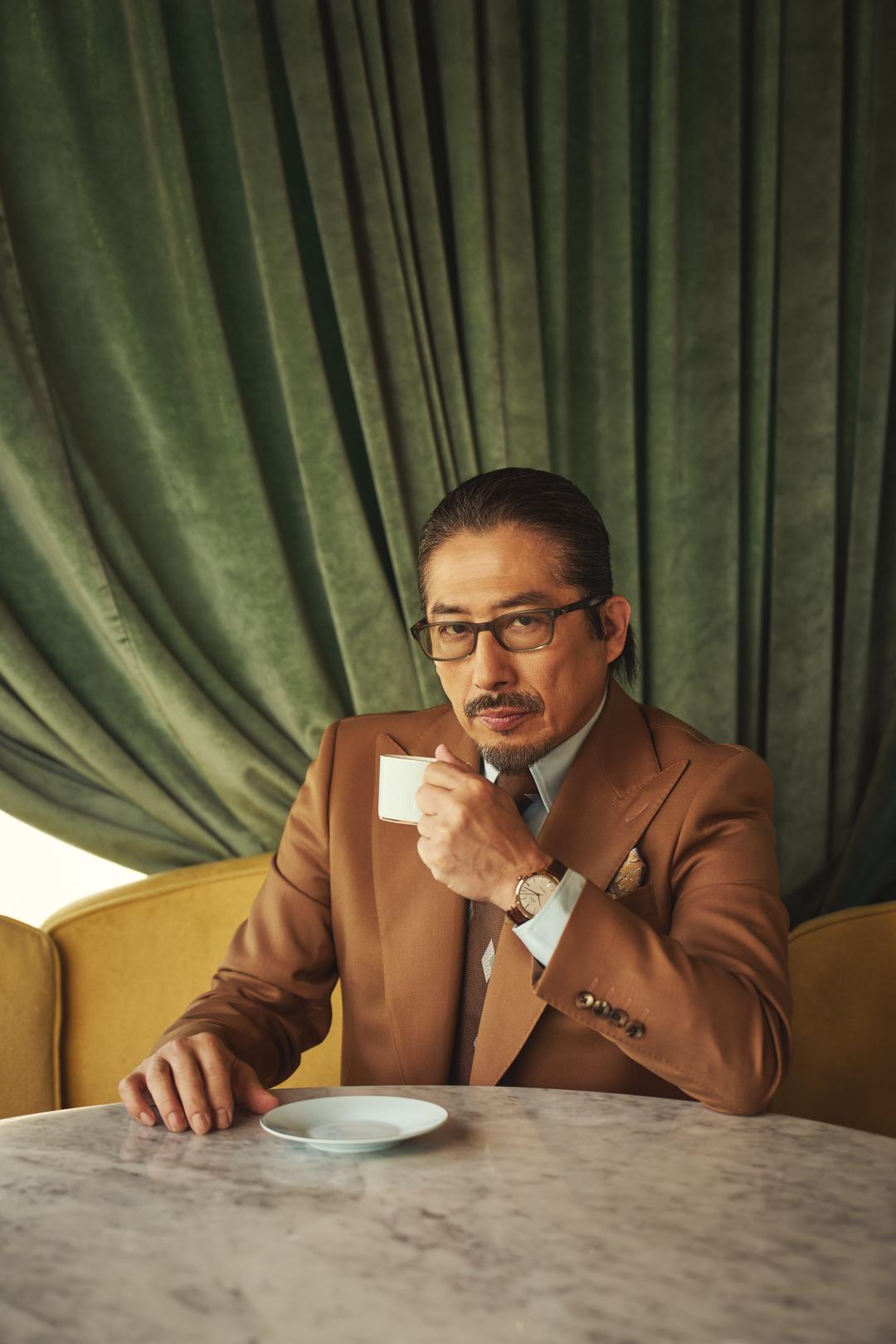

The Last Samurai: Hiroyuki Sanada is The Rake's Issue 95 Cover Star

In nearly six decades in the business, Hiroyuki Sanada has become not just a legendary Japanese actor but a cultural ambassador, enlightening western studios and audiences alike. The star of Shōgun tells Tom Chamberlin about his extraordinary journey.

Several years ago I wrote The Rake’s cover story on Willem Dafoe, and I mentioned that I’d seen a video on YouTube of Dafoe performing before he was famous with his old theatre ensemble, the Wooster Group, in which he was singing on stage with, well, everything on show. It seems the story was read by his diligent publicist, as the video was swiftly removed from YouTube following the magazine’s release.

There is no similar kind of video available of Hiroyuki Sanada. However, there is one clip that you should go and find, and hopefully it will not be removed from YouTube: it shows Sanada playing the Fool in the Royal Shakespeare Company’s 1999 production of King Lear. The set-up is odd, in that it is the first-act ‘Take my coxcomb’ duologue between the Fool and Lear, but in this video a box, twisting like a ballet dancer, delivering the lines with no response, as if it were a monologue — and it works beautifully. To the English-speaking world (and those fortunate and wise enough to have procured a ticket), this will have been their first sighting of Hiroyuki Sanada. Like the 1994 ‘Dinner of the Century’ in Paris that released the Trinidad cigar brand to the public, until King Lear our cover star had been something of a state secret. Today we are grateful that Japan didn’t keep him to itself. Amid the gigawatt success of 2024’s Shōgun, Sanada is in the driving seat and, fortunately for us, on the front of The Rake.

Hiroyuki has become a modern-day Toshiro Mifune, which is a daunting pair of shoes to fill. Mifune was more than an actor, he was a cultural ambassador — his collaborations with Kurosawa, for example, helped demystify Japanese heritage in a respectful and powerful way. Mifune was an action hero in the same way that John Wayne was. However, in the 1950s and sixties, before the civil rights movement had taken hold, and with the second world war very much in people’s memories, the west was far too prone to stereotype, denigrate and disrespect Japanese culture. In a more enlightened society, fascination with the country’s history is still present but many more of the prejudicial barriers have been relegated to the scrapheap. For the past two decades at least, from the release of The Last Samurai (2003), Sanada has become a sort of cultural ambassador-at-large to Hollywood, and it’s about time his efforts were acknowledged. As with the craftsmen we feature in this magazine, Sanada’s story lies not just in the product but in the effort and time he has spent perfecting his craft — and Sanada has been at it a very long time.

I hadn't seen a movie before I started acting... But little by little I started to learn better ways and techniques.

“I hadn’t seen a movie before I started acting,” he says, which seems absurd until you realise he made his first film when he was five years old. He played the son of a yakuza in Game of Chance (1966). The motivation for taking part was understandably rudimentary: “I liked being on set, as if I did something well people would applaud and say ‘good job’. It was like playing around, but little by little I started to learn better ways and techniques. I saw a lot of actors on set who provided both good and bad examples of what to do.”

As a result, the first film he watched was one of his own, in the screening room of the studio. He loved the film world, and that was what made him decide to continue with acting; in fact, he says he never thought about another job in his life. Indeed, he would go on to become one of Japan’s most prolific actors, clocking up 59 movies before Hollywood would ever set eyes on him.

The child actor was, of course, merely parboiled; he had a long way to go before he was a fully cooked professional. The process involved becoming more and more familiar with Japanese dramatic culture. He says: “My first theatre work was the traditional theatre dance that I started learning when I was 12, but I didn’t get on stage till I was 14 and I danced in front of an audience. My first musical was not till I was 20. Little by little I was learning.” It is a journey he reflects on with a slow, considerate, sympathetic retelling of his early career. Perhaps recalling it reminded him of the typical uncertainty that attaches itself to an apprentice of any vocation whose desire is to meet the required standard.

Certainly, the challenges he would face would not get any easier, for his theatre work was about to present him with the chance to perform Shakespeare. His English was not quite to a fluent level, though he had some Shakespearean experience, having played Romeo in 1986 and the Dane in a 1995-1998 production of Hamlet in Japanese. Off the back of that performance, the RSC chose him for their English production of Lear. “This was the biggest challenge in my life, and I was scared when I got the offer,” Sanada says. “I couldn’t answer immediately — actually, for a few months. From the English language and [my] schedule, everything was impossible, because I had movies coming up and I was on the stage already playing Hamlet, so how could I make the time and when can I learn Shakespeare in English when modern English was already so hard for me?”

A gong went off in my head... I thought, In 10 years’ time, which person do you want to be? Life is short, let’s do it.

He aspired to English-speaking roles, but thought they would come initially on screen, because “with movies or T.V. it is ‘take one’, ‘take two’ — you can try things again. But on stage you can’t do that. So I had it mapped out when I was 20 that I could do a movie or T.V. [show] in English and try, try, try [to] attack it. Then, at some point in my life, if I could do Shakespeare on stage, that’s my goal. But the Shakespeare chance came before I could put my plan into place, and that’s why I couldn’t say yes immediately. Then I had producers and Nigel Hawthorne [who played Lear] getting in touch to ask me to join. They said to me, ‘You are an actor before you are Japanese’, and a gong went off in my head. I thought, You can choose this opportunity or not, but in 10 years’ time, which person do you want to be? I thought, Life is short, let’s do it.”

Speaking of gongs, his performance resulted in Hiro-san being honoured with an MBE (Member of the Order of the British Empire). It was notable because he is not British, but on occasion the honours system in the United Kingdom bestows them on citizens of other nations who make a strong contribution to Britain, in this case for his spreading British culture in Japan. This moment perhaps marked the beginning of his cultural impact outside Japan, although considering this was 2002, there was a lot left to come. Indeed, it was about to change irreversibly. Sanada explains: “That was when I did the audition for The Last Samurai.”

In 2003, Tom Cruise did what Tom Cruise does — star in a big-budget blockbuster with a heroic feelgood factor blended with high-octane stunts that brings a new meaning to suffering for one’s art. Cruise’s Captain Nathan Algren was taken to Japan with the mission of using his military nous to train the nascent modern Japanese military and quash a samurai uprising. He is captured by the rebels and, in the words of director Edward Zwick, “What he discovers is that this may not be a culture that is worth getting rid of”. His co-star was Ken Watanabe, but the most memorable character, and the one who goes on the most poetic of journeys with Cruise, is the largely mute Ujio, played by Sanada.

The job had a profound effect on Hiro: “If I didn’t have experience in Shakespeare, I wouldn’t have done the audition for The Last Samurai. I was thinking, No, Hollywood cannot make a samurai movie. But then I thought, They will make this movie whether I like it or not, so what if I do the movie, perhaps I can make a difference on how to make sure culturally everything is right.”

The capacity to do this stems from his days as a child actor, when on set he would have plenty of what he refers to as mentors, who taught him how to hold a cup properly or how to dress. By the time he was on the set of The Last Samurai, he had the numbers of these mentors as well as a trailer full of historical books, so he was able to make sure that when asked, he had the correct answer.

“So that is what I did,” he says. “Even if I had no scene I would be on set making sure the props, costume, extras, movements were all correct. Ed Zwick allowed me to do that, and then asked me to stay for post-production, so I stayed there for six months by myself, and every week we would watch screenings and make notes for every department. At the end, all the chiefs of department called me and they invited me for dinner and said it was to say thank you — ‘Your passion reminds us of when we started filmmaking’.”

It is worth pointing out that a close call almost changed Hollywood as we know it. A malfunction in a mechanical horse meant that Cruise had his neck where it was not intended to be, and a sword wielded by Sanada missed him by a few millimetres.

From a professional point of view, Sanada put into practice the skills he learned at the RSC. “The British style of acting is very simple but very layered, you’re not supposed to move around too much, and I never learned those kinds of things before,” he says. “It is a little like what we had before Kabuki theatre in Japan — we had Noh theatre, which was about subtle movements, using fans to symbolise crying, etc, so the audience could feel something. Kabuki was more about entertaining.”

While Hiro’s motivation seems to veer towards the classical acting tradition, he manages to accomplish the entertainment aspect of performance, too. He has a wonderful screen presence, so even in smaller roles, such as Westworld or Avengers: Endgame, he manages to give the impression of ownership of the samurai genre without ever being repetitive.

As mentioned earlier, what he has become is the Toshiro Mifune of the 21st century. Mifune was the face of the monochrome Kurosawa films such as Rashōmon and Seven Samurai, not to mention his performance as Lord Toranaga in the 1980 version of Shōgun, the same character that Hiro-san plays in this year’s remake (more on this shortly). Mifune was the first matinee idol to breach the western cultural wall and exhibit Japanese culture across the world. Sanada now has the torch Mifune once carried. “Kurosawa films are a great influence for all actors,” he says. “Mifune worked for Kurosawa a lot, and

before shooting I would watch a Kurosawa movie to see if I can pick up some ideas. I try to get something, but then forget everything physical, [so] all I try to keep is what I feel in my heart — it is not mimicry, learn, then forget.”

It is one thing to have the presence and charisma of Mifune; it is another to fill the cultural void he left behind. Sanada feels he is up to the challenge. “I thought, O.K., if there is a wall between east and west, walls can be broken, and I want to build the bridge between us. Another gong went off in my head and I said, ‘That will be my life’s mission’. Which is when I decided to move to L.A. for good. I felt that if I went as a guest, I would be a guest forever, so: just jump in and live there and continue.”

After The Last Samurai he featured in both samurai and non- samurai films, such as alongside Keanu Reeves in 47 Ronin as well as Daniel Espinosa’s thriller-horror Life, alongside Ryan Reynolds, Jake Gyllenhaal and Rebecca Ferguson. After Avengers: Endgame, there was a revival of his character in the Hawkeye series, with Hailee Steinfeld and Jeremy Renner, and the 2021 release of Mortal Kombat, in which he portrayed Scorpion, the sequel for which is due out in 2025. He has also had a succession of terrific roles in high-budget movies, particularly as the Elder in Bullet Train, alongside Brad Pitt, in

which Sanada, by then into his sixties, refused to compromise on his levels of screen combat and aggression (in contrast to the calm and considered presence he has in real life). Then there was his role as John Wick’s trusted friend in John Wick: Chapter 4, where we see the modern incarnation of Japanese and samurai heritage on screen.

These are performances of merit on their own, but they have been somewhat overshadowed by the release this year of Shōgun. Hiro plays the protagonist of the fictional narrative based on the true story of Japanese unification under Tokugawa Ieyasu (who in the show is called Yoshii Toranaga). The series has been described as Game of Thrones meets feudal Japan. The sets and costumes are extraordinary; the intrigue, diplomacy and duplicitous high jinks are gripping ; and the brutality amid the beauty admittedly addictive. For this, Sanada was not just the lead actor but a producer, and brought to bear the experience and knowledge he gained working with Ed Zwick on The Last Samurai to make the most authentic samurai epic ever, with two further seasons commissioned already.

Production: Copious Management

Grooming: Tammy Yi

Photography Team: Kevin McHugh, Col Elmore and Brandon Smith

Fashion Assistant: Helly Pringle

Digital Technician: Brandon Hepworth

Seamstress: Marina Bogin