It's Miller time

In the crucible of post-truth, post-consensus America, Arthur Miller and his morality tales are beacons of light once more.

The soul of the American playwright Arthur Miller is more tangible than ever. Seventy years after the first performance of his incendiary play The Crucible, there was recently a new production at London’s National Theatre, starring House of the Dragon’s Milly Alcock. Adrien Brody played Miller with elegant mystique in Blonde, last year’s unflinching biopic about his wife Marilyn Monroe. Arthur Miller: Writer, the 2017 HBO documentary made by Miller’s daughter Rebecca, revealed new depths and complexities to a figure who, by his own definition, wrote about what was “in the air”, though often from a lateral or allegorical perspective that gave his work an extra prescience.

Arthur Asher Miller was born in October 1915 in Harlem, New York into a family of Jewish-Polish descent. His father, Isidore, owned a successful women’s clothing business that brought the Millers wealth, two houses and a chauffeur, but he lost almost everything in the Wall Street Crash of 1929. To help the family, teenaged Arthur delivered bread every morning before school. As his obituary in The Guardian observed, Miller drew from his father’s financial disaster (like Dickens and Ibsen) a lifelong conviction that catastrophe could strike without warning — a key motif he’d come to explore in his plays.

At the University of Michigan, Miller initially majored in journalism, then changed to English and wrote his first play, No Villain. After graduating in 1938, he turned down a more lucrative role as a scriptwriter for 20th Century Fox to join the Federal Theatre Project, which Congress closed down the following year over fears of Communist infiltration (an early omen of troubles to come). While writing radio plays for CBS, Miller worked as a fitter in the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Excused from world war II because of a high-school football injury to his left knee, in 1940 he married his first wife, Mary Grace Slattery, with whom he had two children. As he once said in an interview with Mike Wallace, he and Mary were “mysteries to each other. She wanted the intellectual, the Jew, the artist. And I wanted America.”

His first produced play, The Man Who Had All The Luck (1944), closed after four performances due to terrible reviews (ironic, given the title). His next play, All My Sons (1947), was more successful. An excoriating tonic to the post-war mood of patriotic optimism, it won Miller his first Tony Award, and The New York Times hailed a “genuine new talent” with an “unusual understanding of the tangled loyalties of human beings”. His next play would be his masterpiece. Death of a Salesman (1948) is a deceptively experimental classical tragedy, simultaneously epic and intimate. Directed by Elia Kazan, it won the Tony Award for best drama, the Pulitzer Prize for drama, and was performed 742 times. In the HBO documentary, The Graduate director Mike Nichols recalls hearing stories of doctors being called for men the day after they’d seen the play because they’d cried all night.

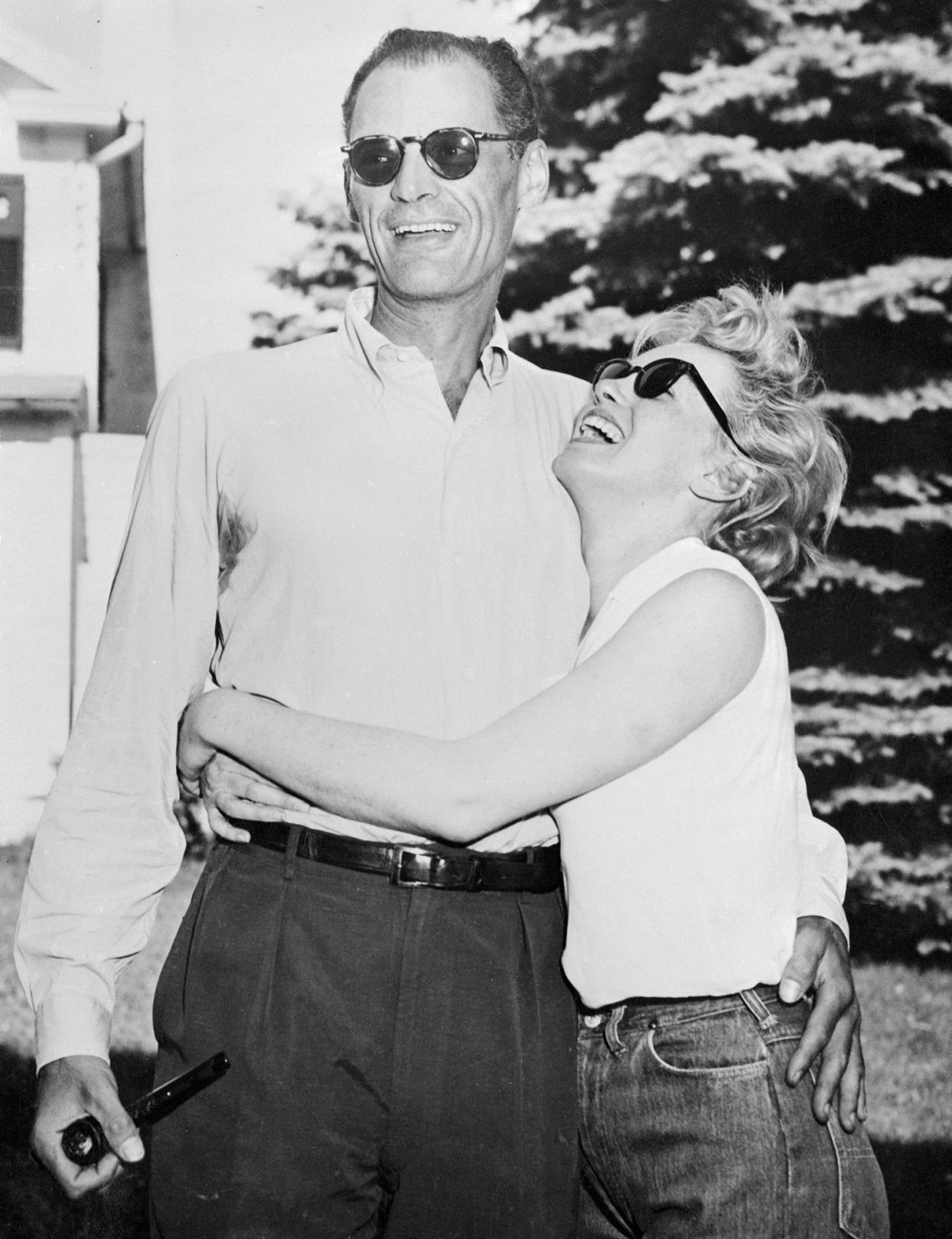

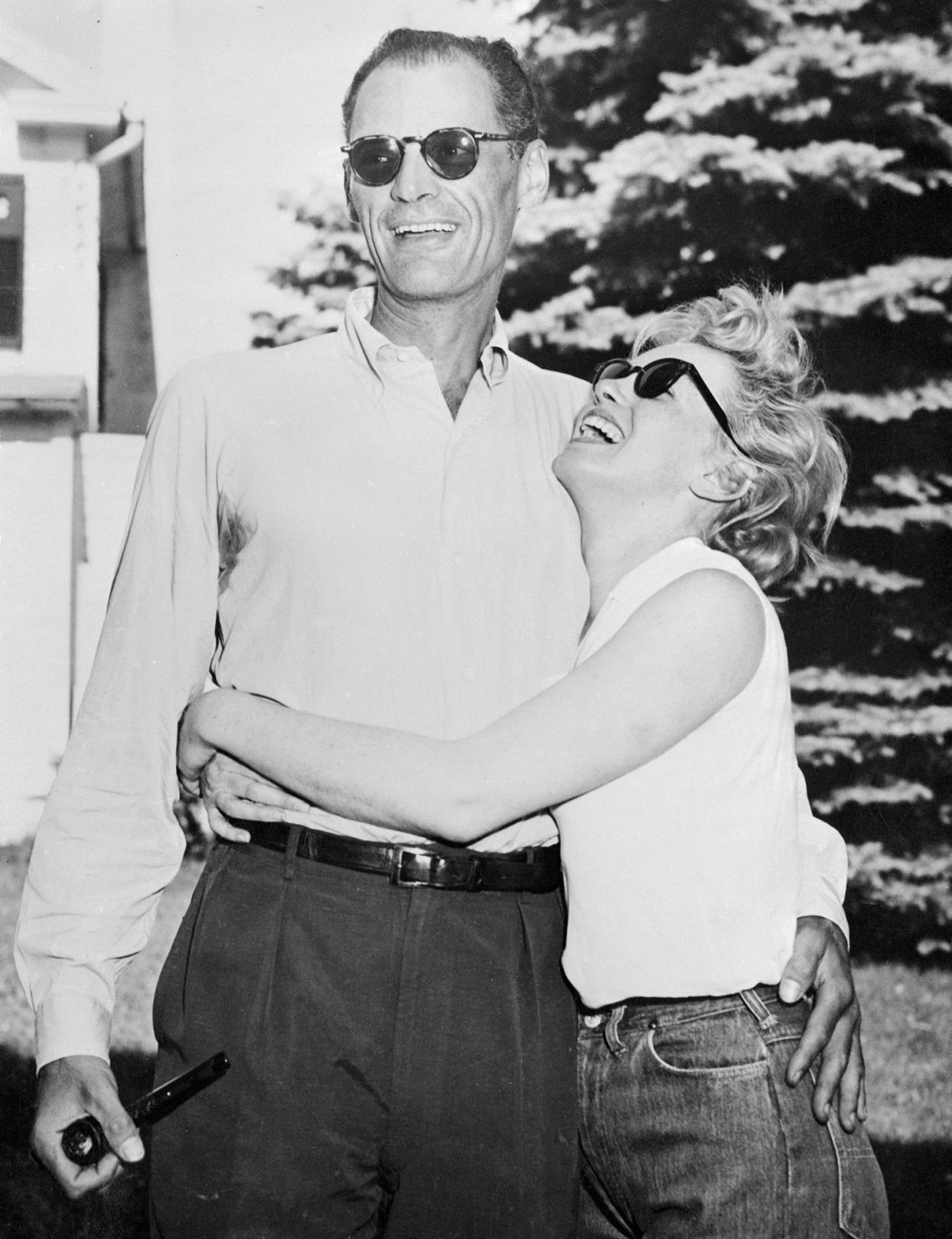

Miller met Monroe in 1951, when he visited the set of a film called As Young as You Feel. As he describes it, she was crying when he met her. They embarked on a brief affair and remained in contact until 1956, when Miller left his first wife, Mary, to marry Marilyn — he was her fourth husband. They were oddly compatible. As Miller said, she was “without guile and utterly honest, whereas the society I came from was very guarded and judgmental”. She was “being cute and making fun of being cute at the same time”.

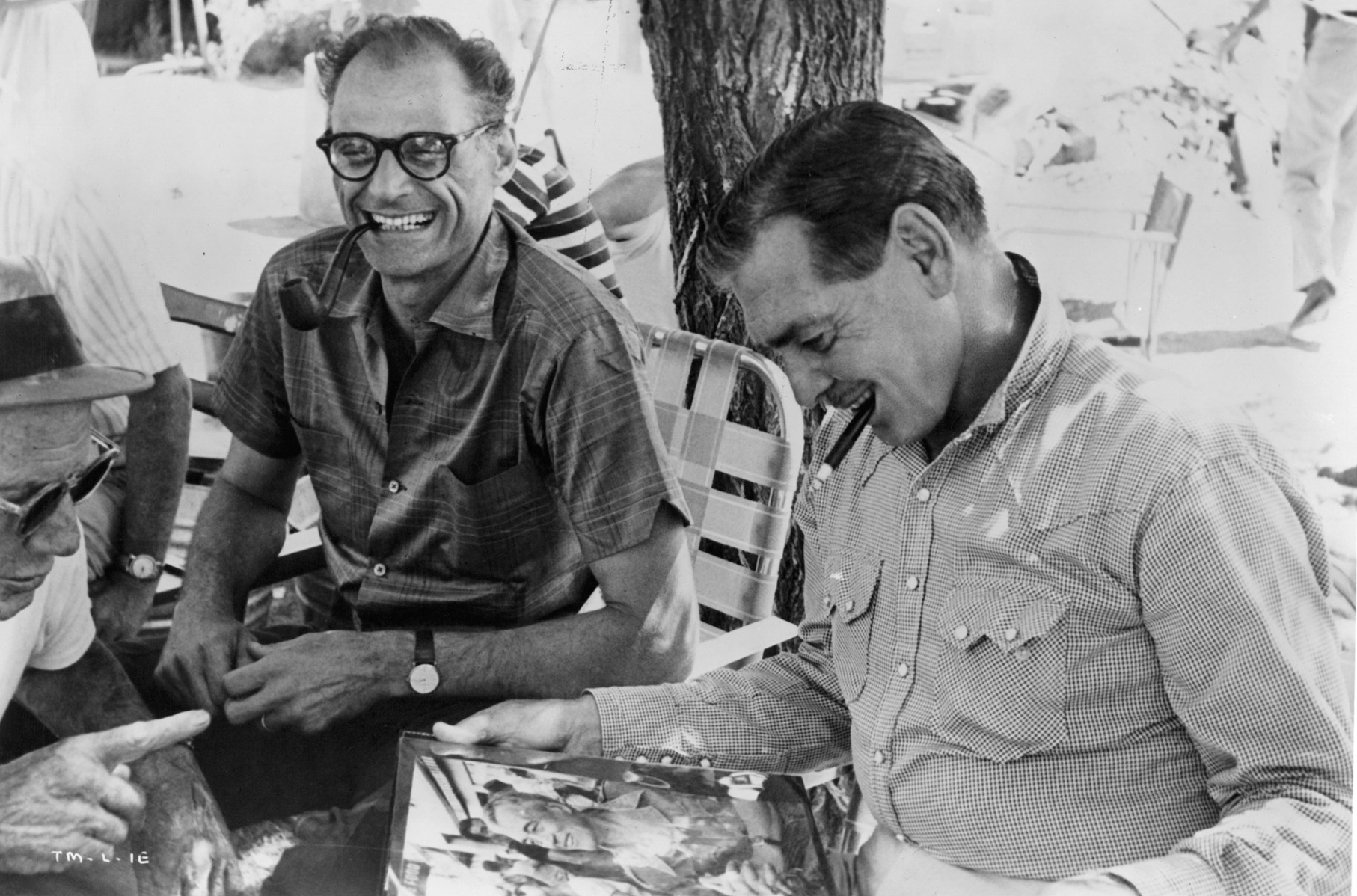

Despite the temptation to see Miller as the bookish old goat, he was extremely stylish, as comfortable in a Brando-esque white T-shirt as a suit. Even Miller’s glasses, with their sleek black frames and prominent single bridge, have recently inspired the likes of Garrett Leight. The severe good looks, sharp cheekbones and fondness for a pipe added to the allure.

Miller’s relationship with Monroe became, and remains, a source of voracious public fascination. As Miller said in a 1987 interview, “The very inappropriateness of our being together was, to me, the sign that it was appropriate... We were two parts of this society... One was sensuous and life-loving, it seemed, while in the centre there was a darkness and tragedy that I didn’t know the dimensions of at that time.” Soon after meeting Monroe, he told her: “You’re the saddest girl I ever met.” She replied: “You’re the only one who ever said that to me.”

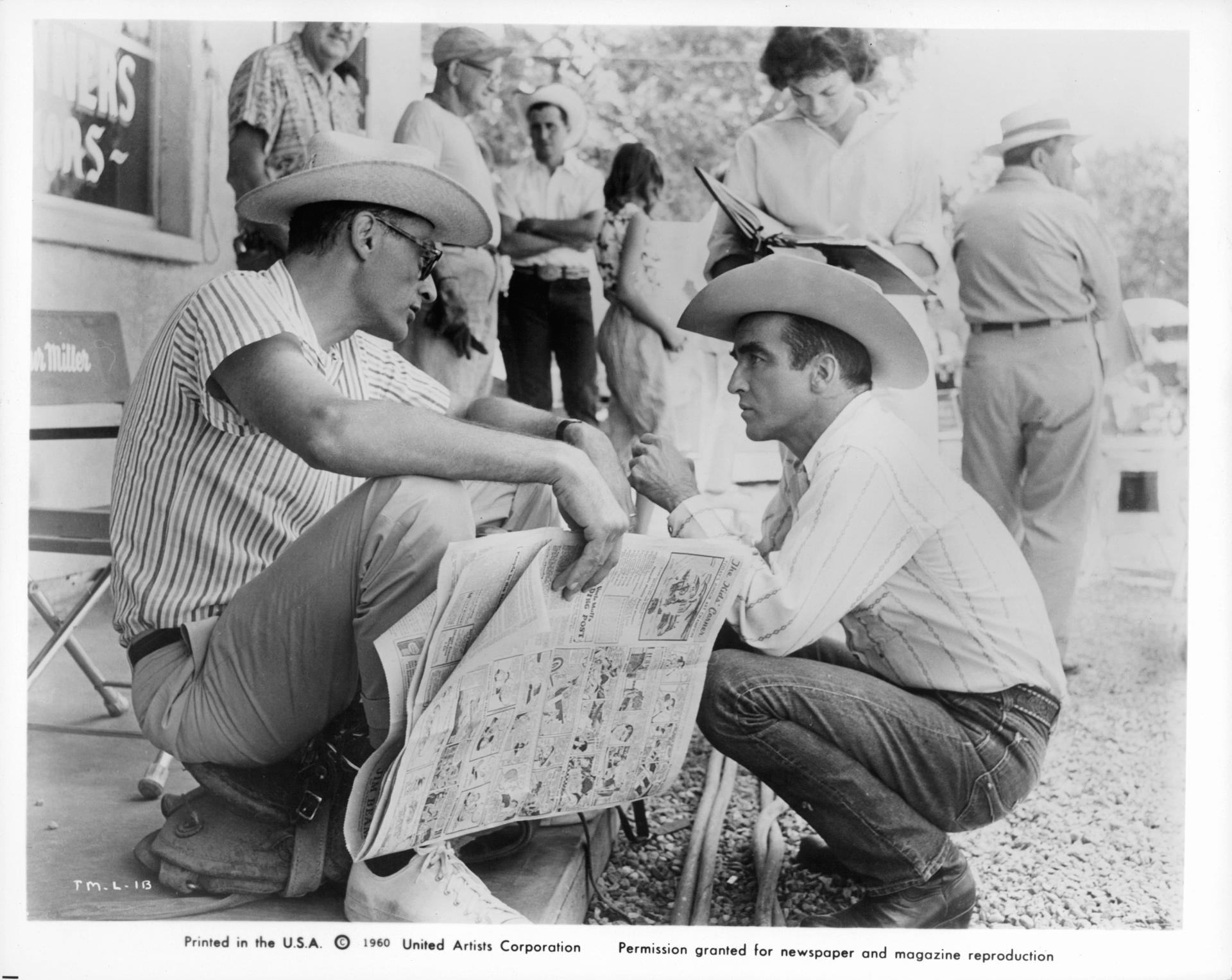

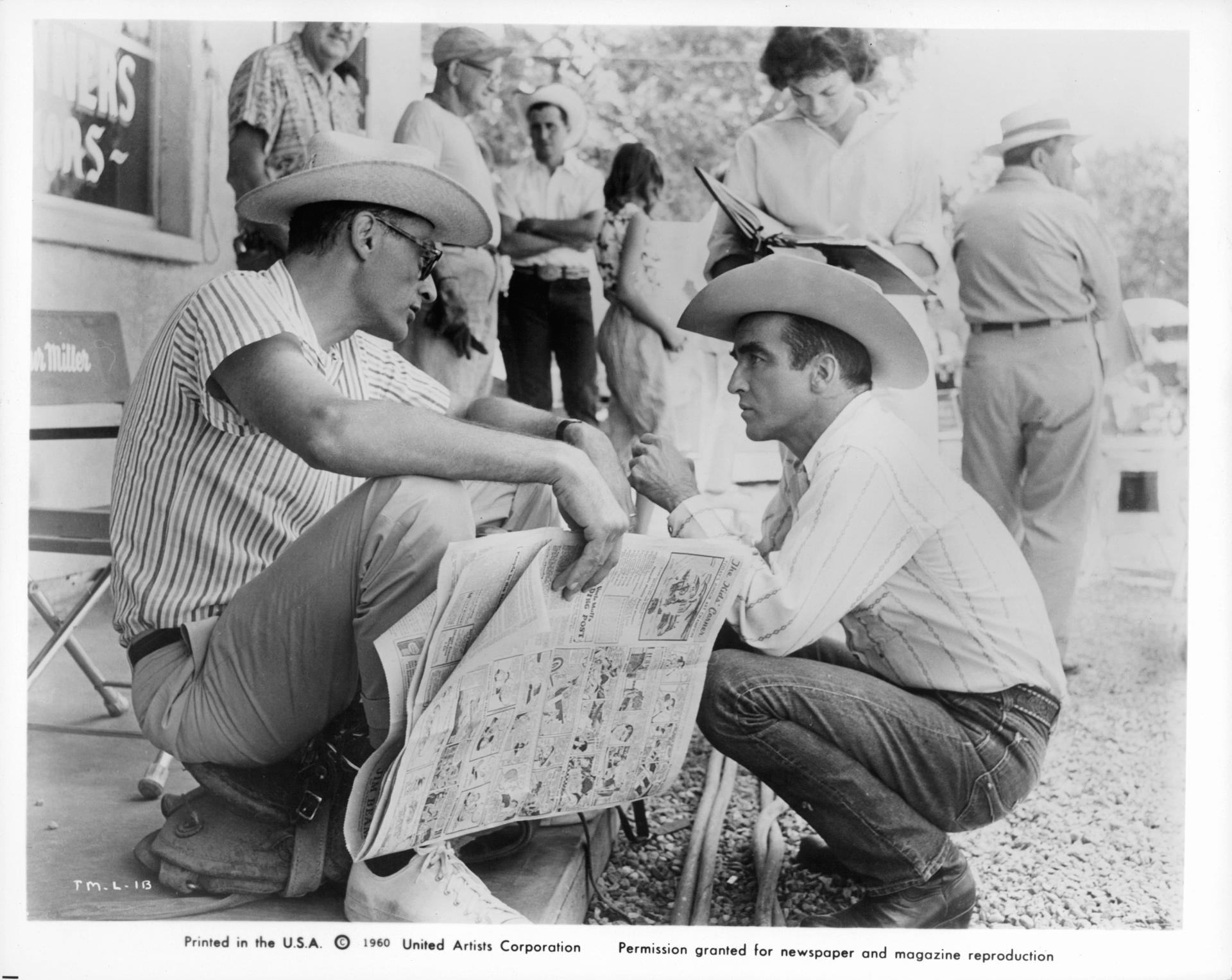

This line was later repurposed for Monroe’s character in The Misfits, a film on which the couple collaborated that was fraught with unhappiness. They divorced shortly before the film’s premiere in 1961, after five years of marriage. The following year, Monroe died of a drug overdose. As Miller said in his acclaimed memoir, Timebends: “It was impossible to guess what she wanted for herself when she herself had no idea beyond the peaceful completion of each day. When she appeared, the future vanished; she seemed without expectations, and this was like freedom. At the same time, the mystery put its own burden on us, the burden of the unknown.”

In the early 1950s, the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) took it upon itself (to quote Miller’s Guardian obituary) to “disinfect the Augean stables of showbiz”.

In 1952, Kazan (Miller’s old friend and Death of a Salesman director) named eight members of the Group Theatre who had allegedly been members of the Communist Party at some point. It destroyed Miller and

Kazan’s friendship. They didn’t speak for 10 years, and Miller channelled some of his anger into his 1955 play A View from the Bridge, in which a longshoreman exposes co-workers motivated by greed and envy. But Miller also noted parallels between the psychology of the HUAC and the Salem witch trials of 1692, especially the obsession with public confession.

Miller would shape those parallels into his next masterpiece, The Crucible, a play that Angels in America writer Tony Kushner characterises as the powerful making an alliance with the mad. With the central character of John Proctor, the play also reflects Miller’s guilt over his first marriage.

Tensions increased when the HUAC denied Miller a passport to attend the London opening of The Crucible. In a brave and stoic performance that had echoes of The Crucible itself, Miller, attending his own hearing in 1957, refused to name friends and colleagues who had participated in similar activities. “I could not use the name of another person and bring trouble on him,” he said. The judge found Miller guilty of contempt of Congress, giving him a fine and a suspended one-year prison sentence, but it was overturned the following year by the court of appeals, who ruled that Miller had been misled by the chairman of the HUAC.

In February 1962 he married the Austrian photographer Inge Morath, with whom he stayed until her death in 2002. They had two children: Rebecca (who would marry the actor Daniel Day- Lewis) and Daniel. But Marilyn was still in the ether. Some felt that his play After the Fall (1964), for which he reunited with Kazan, was too explicit an account of his marriage to Monroe, and too soon. But as Miller would later say, “The best work that anyone can write is the work that is on the verge of embarrassing them”.

Read the full story on Issue 90, available now.

Photography: Getty Images