Serge Gainsbourg: Master Provocateur

Originally published in issue 57 of The Rake, Stuart Husband writes that Serge Gainsbourg was a Gallic colossus of the 20th century, writing songs for, and having affairs with, some of the era’s most beautiful women, and his gift for shocking the bourgeoisie was nonpareil.

In a recent interview, Jane Birkin described her first date with Serge Gainsbourg. They met on the set of the 1969 movie Slogan; he was 40, she was 22. “He barely spoke to me and I thought him terribly arrogant and unkind,” she recalled, “so the director suggested we go out for the night. We went to dinner, then to a club, where I dragged him onto the dancefloor. He trod all over my toes, and I realised that under the rashness and the mauve shirt, he was devastatingly unsure of himself, and that made him terribly intriguing. Then he whizzed me off to the Rasputin club, where he made all the musicians play Sibelius’ Valse Triste while he threw 100-franc notes at them, saying, ‘C’est des putes, comme moi’ — ‘They’re prostitutes, like me’. Then we went off to another club where all the men were dressed up as ladies, to my amazement, kissing Serge on the forehead and saying, ‘Ooh, petit chou-chou’. His father had been a cabaret musician, and they’d all known him since he was tiny, and obviously thought he was a darling. By then it was 4am, and we went back to the Hilton hotel, where the desk clerk said, ‘Your usual room, M. Gainsbourg?’ I thought, Uh-oh, but luckily Serge immediately fell asleep.”

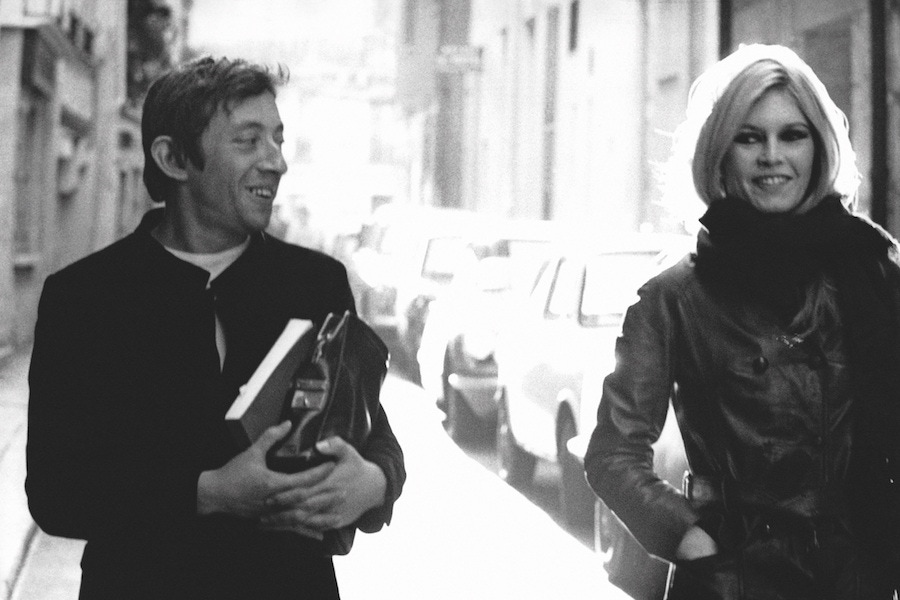

This picaresque tale sums up Gainsbourg’s many facets: louche, naturally; goading, of course; a boulevardier, no doubt; but also oddly artless and innocent. This Gallic colossus of the second half of the 20th century — singer, songwriter, musician, painter, actor, director, smoker, alcoholic, romantic, ladies’ man, and revered national treasure — exploited his contradictions triumphantly. A self-confessed “freakishly ugly” man, with his jug ears, turtle eyes and huge hooked nose (in Joann Sfar’s biopic Gainsbourg: A Heroic Life, he’s represented by a golem-like puppet that resembles the Count from Sesame Street), he wrote songs for and had affairs with some of the era’s most beautiful women, including Brigitte Bardot, Juliette Gréco, and Catherine Deneuve. He thought nothing of marrying high and low culture, adapting the romantic sweep of a Chopin etude, say, for a song about the joys of sex on an ocean liner, or in the cabin of a truck, or just about anywhere. He was a punctiliously tax-paying prude (“I never saw him completely naked,” said Birkin, despite the fact they had a daughter, Charlotte, together) whose most famous hit, the orgasmo-tastic Je T’Aime…Moi Non Plus, was banned by the BBC and the Vatican. He was equal parts Baudelaire, Byron, Johnny Rotten, Stephen Sondheim, and Benny Hill. He said things like “I am incapable of mediocrity” alongside “I’ve succeeded at everything except my life”.

Gainsbourg had been born Lucien Ginsburg in Paris in 1928; his parents had escaped czarist Russia in 1919. His classically trained father played piano in clubs and casinos. “We were raised in a culture of beauty,” said Gainsbourg’s elder sister, Jacqueline. “Painting, music, literature, and the avant-garde — we heard Chopin, Stravinsky, Ravel.” Gainsbourg, conscious of his looks, ping-ponged between wanting to look like the American movie star Robert Taylor and declaring, “I prefer ugliness to beauty, because ugliness endures”. He started to smoke and drink at 20, when he went into the army; on his discharge, he attended the Academie des Beaux-Arts, but dismissed “the bohemian life of the painter” in favour of songwriting. (As soon as he started performing and writing, he changed his name to Serge, both to reflect his Russian heritage, and, according to Birkin, because “‘Lucien’ reminded him of a gentleman’s hairdresser”.) The jazz chanteuse and actress Gréco was the first to record an E.P. of his songs — including the smoky snap of La Javanaise — in 1959, but fame came to him via the unlikely route of the Eurovision song contest.

In 1965, France Gall — then a perky 18-year-old exponent of ye-ye pop — won the latter with the Gainsbourg-penned Poupée de Cire, Poupée de Son (Wax Doll, Rag Doll); the lyrics implied that Gall was nothing but Gainsbourg’s barely post-pubescent puppet, an impression he did nothing to dampen by declaring her “France’s Lolita” and presenting her with a follow-up called Les Sucettes (Lollipops) in which, over a beguilingly tender melody, Gall sings about how she’s “in paradise” every time “that little stick is on my tongue”. When it was explained to Gall that the song might have been about more than the simple enjoyment of a Chupa Chup, she never worked with or spoke to Gainsbourg again. The latter merely shrugged. “To me, provocation is oxygen,” he said.

That credo would come to fruition a couple of years later, when Gainsbourg became infatuated with the 19-year-old Bardot, who, having hit a rocky patch in her marriage to German businessman Gunter Sachs, agreed to go on a date with Gainsbourg. So intimidated was he — “I was scared of her breasts,” he later told Birkin — that he fell over himself to accede to Bardot’s wishes that, in compensation for his crassness, he should go off and write her the most beautiful love song ever heard. In one feverish night, he created two: Bonnie and Clyde and Je T’Aime…Moi Non Plus. The former was a jerky ballad in which Gainsbourg and Bardot channelled the outlaw cool of American bank robbers Parker & Barrow, while the latter was an organ-driven fantasia (no pun intended) that Gainsbourg called “an anti-fuck song about the desperation and impossibility of physical love”, which just happened to be punctuated by Bardot’s moans, yelps, and sighs of pleasure — “the pop equivalent of an Emmanuelle movie”, as The Observer Music Monthly magazine called it. Sound engineer William Flageollet claimed to have witnessed “heavy petting” in the vocal booth during the song’s most torrid moments, and Bardot revoked her consent for its release after Sachs, not unreasonably, took umbrage (it eventually saw the light of day in 1986, with Bardot calling Gainsbourg “a lord” and the song “a hymn to love”).

So it was something of a relief for Gainsbourg when he ran into Birkin, the willowy English actress and singer who had previously been married to the composer John Barry. After their initial epic night out, the couple went off to stay in a suite at Venice’s Gritti Palace and quickly became inseparable. “I was a complete contrast to Bardot,” Birkin has said. “When Serge met me, he said, ‘Wow, you have a body just like the ones I drew in art school’. He didn’t like bosoms to be high and pert; he liked them lower down, which was just as well, as I’d had a baby. ‘I’ve always dreamt of a girl who had the top of a boy and the bottom of a girl,’ he once told me.” Birkin also styled Gainsbourg up: “I put him in those double-breasted woollen Paletot coats with the upturned collars. He wanted shoes that felt like gloves, so I got him white Repetto ballet shoes, which he wore without socks. I bought him jewellery and encouraged him to keep a three-day stubble on his face. I thought he looked very existential.”

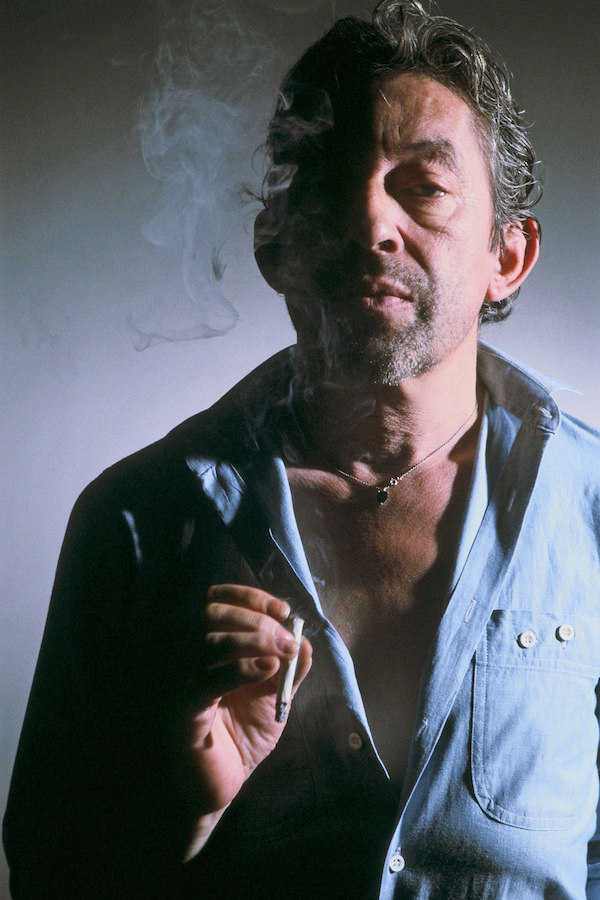

Gainsbourg then paid Birkin the ultimate compliment, asking her to re-record Je T’Aime with him. “He wanted me to sing like a choirboy,” recalled Birkin, “and I overdid the gasping somewhat”, all of which — spurred by worldwide bans and attendant outrage — took it to No.1 in dozens of countries (in the U.S. it stalled at the highly appropriate position of 69). Gainsbourg revelled in his notoriety, buying a Rolls-Royce Silver Ghost in racing green despite having no licence (“You cannot drink and drive,” he said, “and I have chosen”), and propping up the bar of the Paris Ritz while working his way through all the different coloured liqueurs. Through it all, he produced dozens of dazzling songs, including the only pop hit about a scuppered supertanker (1967’s Torrey Canyon) and a 1971 concept album (Histoire de Melody Nelson) about a middle-aged Frenchman who knocks a girl from Sunderland (Gainsbourg thought the former shipbuilding town’s name sounded très exotique) off her bike before taking her home and seducing her; its dark atmospherics would influence a whole generation of later artists, from Beck to Nick Cave.

Gainsbourg had the first of two heart attacks in 1973. “On the way to the American Hospital,” says Birkin, “he insisted on taking his Hermès blanket because he didn’t like the one they had on the stretcher, and he also grabbed two cartons of Gitanes.” During his last two decades, he found various ingenious ways of continuing to épater la bourgeoisie, recording a duet with his 13-year-old daughter, Charlotte, called Lemon Incest, producing a reggae version of La Marseillaise, telling a 23-year-old Whitney Houston on live T.V. that he wanted to fuck her, and burning a 500-franc note on another chat show while railing against “the whore of socialism”. The bourgeoisie, of course, lapped it up, and the outpouring of grief when Gainsbourg died of his second heart attack, a month shy of his 63rd birthday in 1991, was immense, with the then French president, François Mitterrand, lauding him as “our Apollinaire… he elevated the song to the level of art”.

Since his death, Gainsbourg’s reputation has grown, with his songs recorded in English by former Nick Cave sideman Mick Harvey, and Birkin re-recording selections from the back catalogue with both Arab musicians and a full symphony orchestra. She and Charlotte (an acclaimed singer and actress in her own right) are also campaigning to have Gainsbourg’s small, graffiti-covered Paris house, at 5 bis Rue de Verneuil on the Rive Gauche, converted into a museum. Inside is just as Gainsbourg left it: black felt walls (inspired by the astrakhan walls in the house of Salvador Dalí, an icon of Gainsbourg’s; he claimed he’d once got hold of the keys to Dalí’s house and made love in every one of its rooms with his first wife while Dalí was elsewhere); ashtrays scattered over every surface; photos of Birkin, Bardot and Gréco, along with other women who recorded his songs, including Françoise Hardy, Isabelle Adjani, and Vanessa Paradis; a black lacquered bar with a cocktail shaker and glasses; pinstripe suits in the hall closet; and a mink-draped bed in the mirrored master bedroom. If that isn’t enough to give future visitors a flavour of Gainsbourg the incorrigible (if ingenuous) roué, they could always play his mission statement, La Décadanse, over the speakers:

La décadanse

Plus encore

Que notre mort

Lié nos âmes

Et nos corps.

This article originally appeared in Issue 57 of The Rake.