What It’s Like to Navigate the Mille Miglia

The famous Italian race was the endurance event of the early 20th century. It’s no longer a competitive race, but it’s just as special.

Sir Stirling Moss never won a Formula One world championship. He lost out on four consecutive occasions in 1955, ’56, ’57 and ’58, finishing second behind Juan Manuel Fangio in three of them. But he did win perhaps the most gruelling race of all, and one with no less prestige: the Mille Miglia. In 1955, Moss beat his old rival Fangio in spectacular fashion, with the Argentine crossing the finish line some 32 minutes behind the Brit. Moss and his co-driver Denis Jenkinson took just 10 hours, 7 minutes and 48 seconds to complete the 1,000-mile route from Brescia down to Rome and then back up again, in front of hundreds of thousands of spectators. Their ‘722’ Mercedes-Benz 300SLR averaged just under 100mph, setting a record that would stand forever.

In his write-up for Motor Sport magazine, the co-driver and journalist Jenkinson regaled, “As we were driven back to our hotel, tired, filthy, oily and covered in dust and dirt, we grinned happily at each other’s black face and Stirling said “I feel we have made up for the two cars we wrote off in practice,” then he gave a chuckle and said, “We’ve rather made a mess of the record, haven’t we — sort of spoilt it for anyone else, for there probably won’t be another completely dry Mille Miglia for twenty years.”

Just two years later in 1957, the Mille Miglia would change forever, following a tragic accident in which eleven people died. Three days after the race, the Italian government banned racing from taking place on public roads, so Moss’ feat would never be beaten. Today, the Mille Miglia continues. It is now a regularity race in which entrants must drive cars that were entered in the original period races from 1927 (the first ever Mille Miglia) to the last in ’57. The route is very similar to the original, beginning in Brescia before descending down to Turin, Viareggio, Rome and then back up through Siena, Bologna and finishing on the streets of Brescia.

It’s one huge lap of Italy, taking in rolling countryside hills, small hamlets, cobblestone villages and major cities. Large portions of the original route are still driven, including the Futa Pass, where Moss would have flown down at over 100mph. Now, like then, you must get your timecard stamped at various checkpoints. These are usually within the beautiful main squares of various Italian towns, where locals show out to clap, cheer and high-five you onwards. Now, to win the Mille Miglia you must cover ground not the quickest, but by a certain timeframe. The closer you are to the time given, the more points you earn.

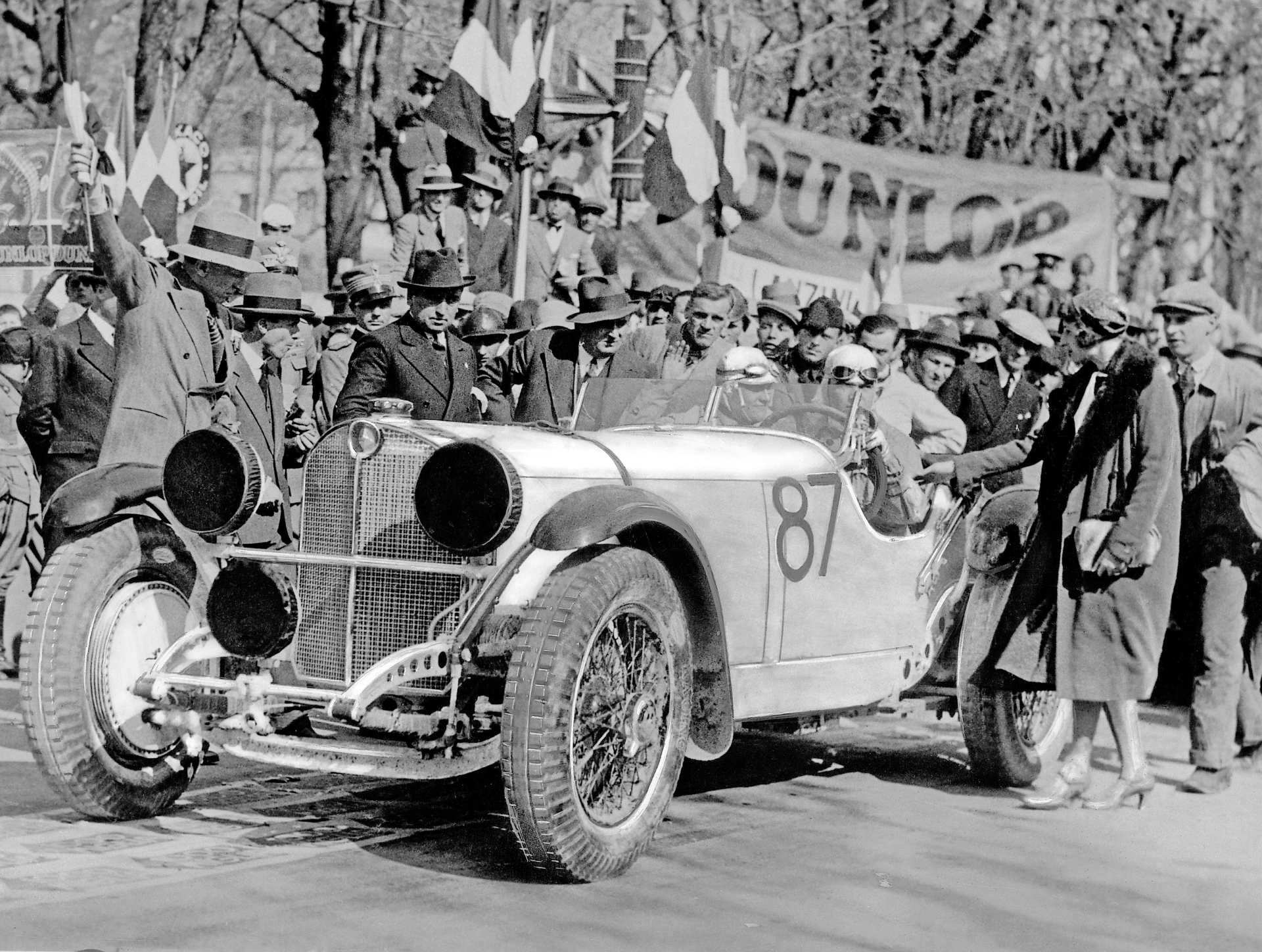

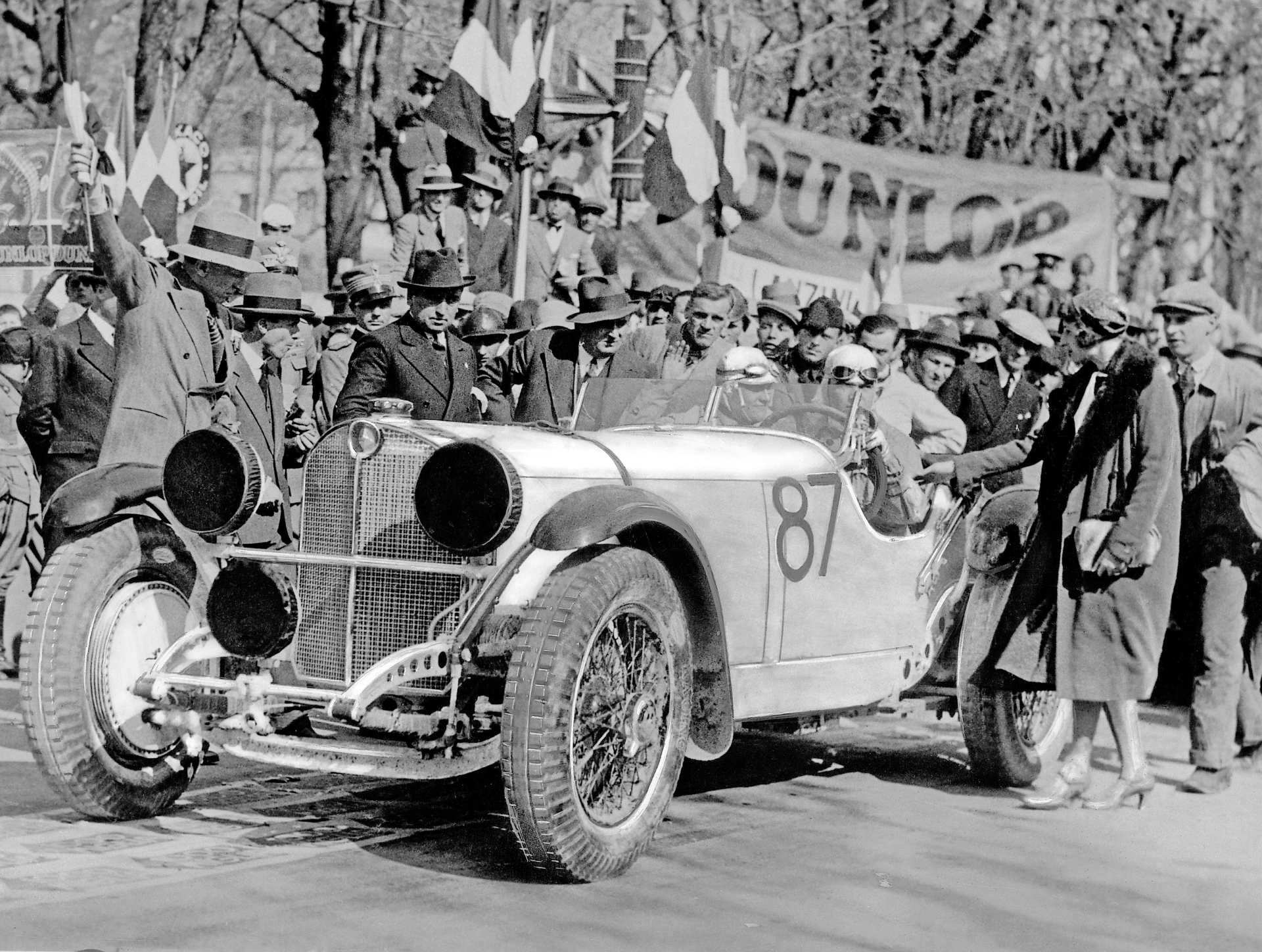

I joined this year’s Mille Miglia with the Mercedes-Benz works team, and it wasn’t my goal to win but to get through it. Like Jenkinson I would be the co-driver, helping Marcus Breitschwerdt, head of Mercedes-Benz Heritage to wrestle our steed through the narrow Italian streets. Our car was not a light and nimble 300SL, but a colossal Super Sport from 1930, originally built for the Maharajah of Kashmir. Unlike Jenkinson, I was a complete co-driving novice, with little experience of reading a roadbook and even worse maths skills.

It was my job to navigate us on the longest leg of the five-day race, covering a total of 365 miles from Rome to Bologna, beginning at 6.20 am and ending in the night halfway up the country. The car and Marcus’ driving were impressive in equal measure. The 7.1-litre straight-six engine was heroic, with its mechanical whirs and a booming exhaust note that sounded like nothing else on the road. Its gearbox isn’t synchronised so you have to double clutch to shift, the pedals are the wrong way around and the huge steering wheel must be grappled with force through every bend. Marcus showed me the car’s party trick: a kick down of the pedal engaged the compressor supercharger, which wailed to life, forcing air to the carburettors and adding a further 40hp, which increases the total to 200hp. In the ‘30s, fans nicknamed its sister cars, which were finished in Germany’s national racing colour, ‘white elephants’, because of the noise. In 1931, a similar SSKL won the Mille Miglia, demonstrating the speed of these behemoths.

This particular model was built to match the Maharaja’s yacht, which was finished in a grey and beige colour scheme. Its interior is indeed boat-like, with a varnished wood dashboard, multiple mechanical dials, chrome accenting and that huge steering wheel. It is built more like a mechanical watch than a car, with an attention to detail and finish that is akin to high jewellery. Similar cars live permanently in Mercedes’ museum in Stuttgart, but this one, worth in the region of £8-£10 million, is driven hard.

This is something the Italian spectators appreciate. They turn out in the thousands, lining the streets of each town, spurring you on, but also in the middle-of-nowhere countryside. They welcome the SS like a beloved celebrity, shouting, gesturing and smiling with pure enthusiasm. Men, women, children, grandparents. Whole families. They are there in the morning at sunrise, and they are there in the middle of the night with their camera flashes appearing out of the darkness. We arrive in Bologna at 11.20 pm to the slightly inebriated crowds who, wine glass in hand, toast you as you pass the restaurants and bars. Thumping dance music accompanies the straight six, and the air is laced with garlic and petrol. The people are crazed now, jumping and waving frenziedly, and the car is hot and needs to cool down. As do I. The Mille Miglia might not be a competitive race any more, but the magic is still very much there.