BLACK JACK’S ACE

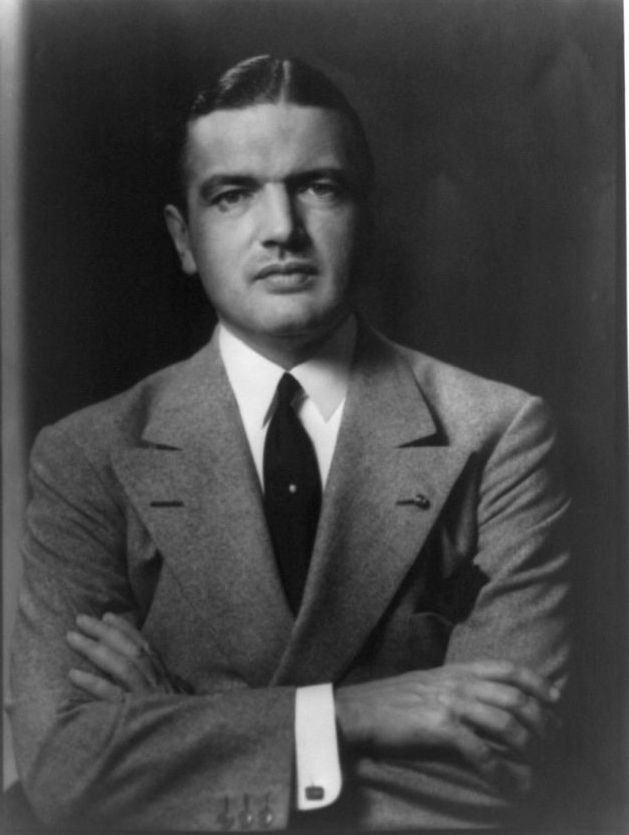

His dubious parenting style and numerous character flaws aside, looking at John Vernou Bouvier III, it isn’t difficult to surmise where his famous daughters Jackie and Lee got their good looks, innate style and magnetic charisma...

‘Black Jack’ Bouvier was many things — a boulevardier, an inveterate risk-taker, a heavy drinker, the father of Jackie Onassis (née Kennedy, née Bouvier), a narcissist, and a ringer for Clark Gable; appropriately so, since Gable-as-Rhett Butler’s fabled parting shot in Gone with the Wind — “Frankly, my dear, I don’t give a damn” — could have been Black Jack’s mission statement.

His haughty insouciance was one of Black Jack’s ineffable birthrights, along with a fastidious elegance and a notable appetite for self-destruction. He was born John Vernou Bouvier III in East Hampton in 1891; his father, Major John Vernou Bouvier, Jr. was known to all as ‘the Major’, due more to his overbearing mien than to his brief spell in military service. The Bouviers were descended from a line of southern French Catholic artisans, but the Major, finding this genealogy insufficiently illustrious, commissioned a treatise titled Our Forebears that forged a concocted link to Plantagenetesque aristocrats (family members would always insist on pronouncing Jackie’s name ‘Jack-Leen’, in strangulated haute-French style).

Black Jack (the piratical soubriquet came from his extremely dark Bouvier complexion, spawning other nicknames, including ‘the Sheikh’ and ‘Black Orchid’) was the heir to a family fortune made on Wall Street and in real-estate speculation, and the Major drummed a sense of entitlement into him, along with a keen sense of style. The Major’s favoured East Hampton Sunday attire consisted of a brown tweed jacket, a white shirt with high, stiff collar, white linen trousers, black socks and white shoes. He was also the proud possessor of a Hercule Poirot-style moustache, painstakingly waxed every morning until the points formed a perfect 90° angle to his cheeks.

Black Jack followed facial-adornment suit with his own pencil-thin Gable-esque number, which only added to his movie-star allure. His thick black hair was assiduously groomed, with an arrow-straight parting; his piercing blue eyes were complemented by full, sensual lips and a muscular physique that he maintained by working out in a private gym or at the Yale Club (later, he would sweat around the Central Park reservoir in a specially-commissioned bespoke rubber suit, possibly the first instance of a gimp-style weight-loss programme). He topped up his tan by sunbathing naked at the window of his Park Avenue apartment, or in the men’s cabana area of the Maidstone Club.

He topped up his tan by sunbathing naked at the window of his Park Avenue apartment, or in the men’s cabana area of the Maidstone Club.

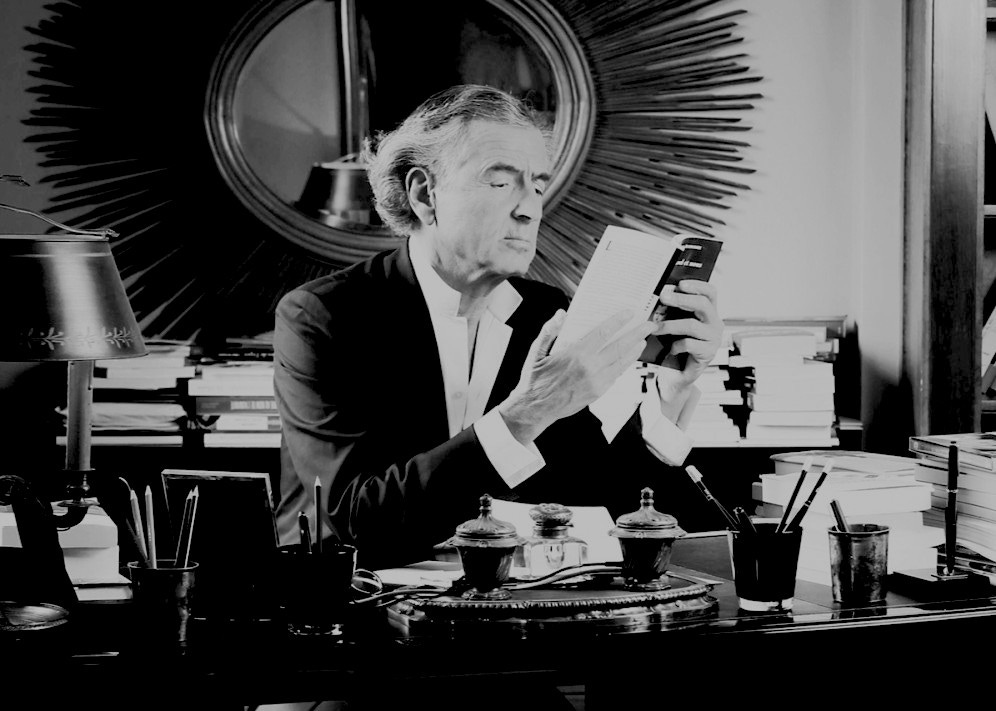

"He topped up his tan by sunbathing naked at the window of his Park Avenue apartment, or in the men’s cabana area of the Maidstone Club"His suits were tailored just that little bit more expansively than those of his peers — wider lapels, boxier shoulders, more elaborate drapes, extravagant DB frontage — to complement his high-collared Brooks Brothers shirts and modishly-pinned rep ties; even at the zenith of an East Hampton summer, he was never seen out of an immaculate gabardine suit.

He also displayed the full complement of those recalcitrant traits native to the scion-playboy. He was a chronic gambler both at the racetrack and on the stock exchange, where he worked as a fairly mediocre broker, and had been expelled for gambling from his prep school, Phillips Exeter. He was pathologically uninterested in intellectual or cultural pursuits, and his academic record was abysmal; at Yale, he majored in parties (both giving and attending, with bevies of pretty girls in tow either way), and was a compulsive womaniser.

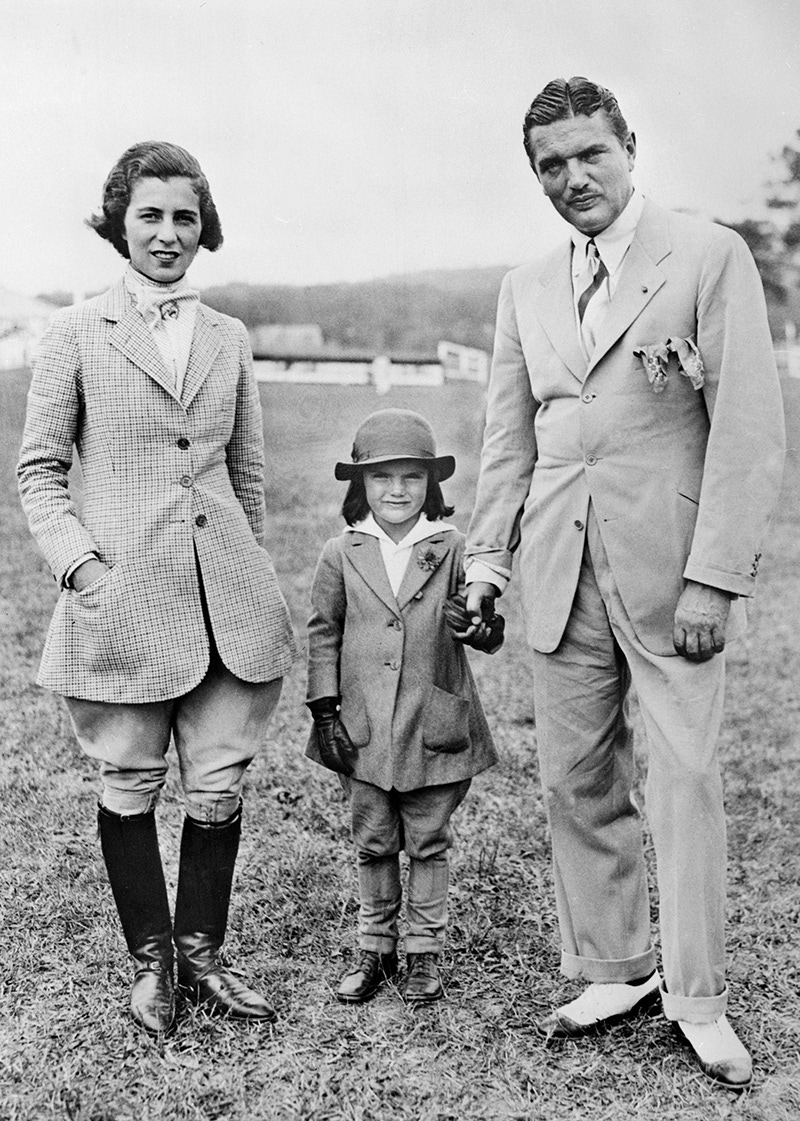

Black Jack was 37 when he finally married Janet Norton Lee; she came from impeccable WASP stock, and was effortlessly chic, but also steely — she’s been described as having “a whim of iron”. It was generally considered that she’d ‘married up’, but even on their honeymoon, sailing to Europe on the Aquitania, Black Jack embarked on a shipboard flirtation with the Newport heiress Doris Duke. Later, in Biarritz, he promptly lost all their money in the casino (Janet, showing enviable sangfroid, gathered together the remaining chump change, went off to the gaming tables herself, and won it all back).

For Black Jack, Janet was a classy adornment, particularly on horseback (she won prizes at shows throughout the east, and was feted in the society pages for wearing “the smartest riding habits in Long Island”), but she failed to make a significant dent in his overweening self-regard. He was never happier than when in front of a camera, smoothing his hair and adjusting his tie just-so, reveling in his instinctive sense of theatre and his central place in the spotlight — qualities he would pass on to his daughters Jackie and Lee, to whom he acted more like a lover than a father, flirting with them and stirring things up by singling one or the other out for extravagant praise — “Lee’s going to be a real glamour girl some day. Will you look at those eyes... and those sexy lips of hers?” or “Doesn’t Jackie look terrific? Girl’s taken all prizes in her class this year... and she’s the prettiest thing in the ring to boot.” These effusions became known in the family as ‘Vitamin P’.

Further proof that Black Jack was congenitally unsuited to family life wasn’t slow in coming — perhaps it was the serial showgirl parties he threw while his wife and daughters were upstate, or the fact that a picture of Janet appeared in the New York Daily News with her husband openly holding the hand of a pretty young woman named Virginia Kernochan behind her back — and in 1936, he moved out to a room at the Westbury Hotel; no great hardship, as its Polo Bar was one of his favourite rendezvous for assignations. The nal break was announced in the New York Daily Mirror in 1940, under the heading “Society Broker Sued for Divorce”, with further unedifying details — names, dates, photographs — of his various extramarital conquests. Black Jack was now at bay, succumbing to the alcoholism that would prevent him from walking Jackie down the aisle at her 1953 wedding to John F. Kennedy (her stepfather, Hugh Auchincloss, did the honours instead), and that would eventually kill him. By the time of his death, four years later at the age of 66, he was just a shadow of his former self — but what a self. Incorrigible, indomitable, and an exemplar to a legion of cocksure dandies-in-waiting. “All’s fair in love and war,” as his other life motto had it, to which he would add, with lip-smacking, who-would-know-better-than-me relish: “Because all men are rats.”