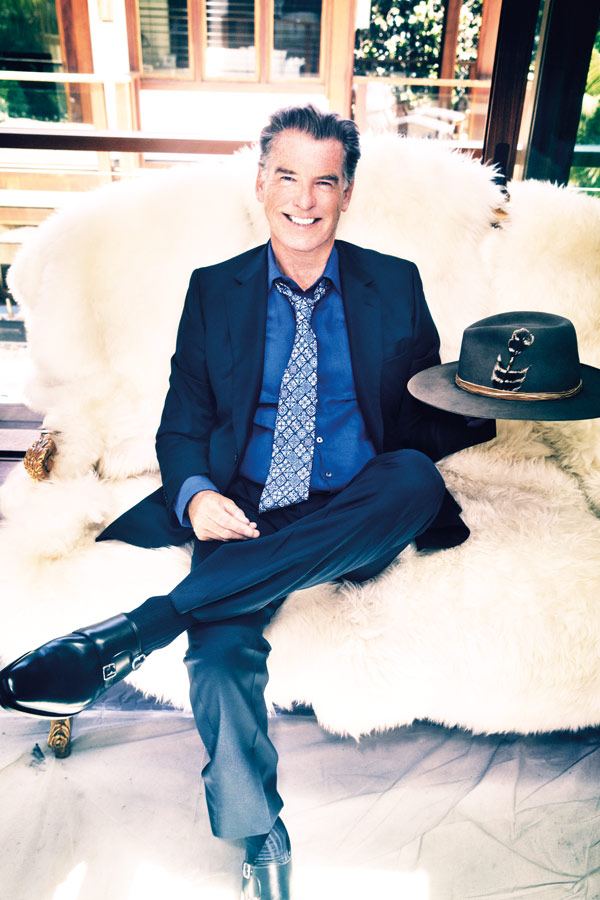

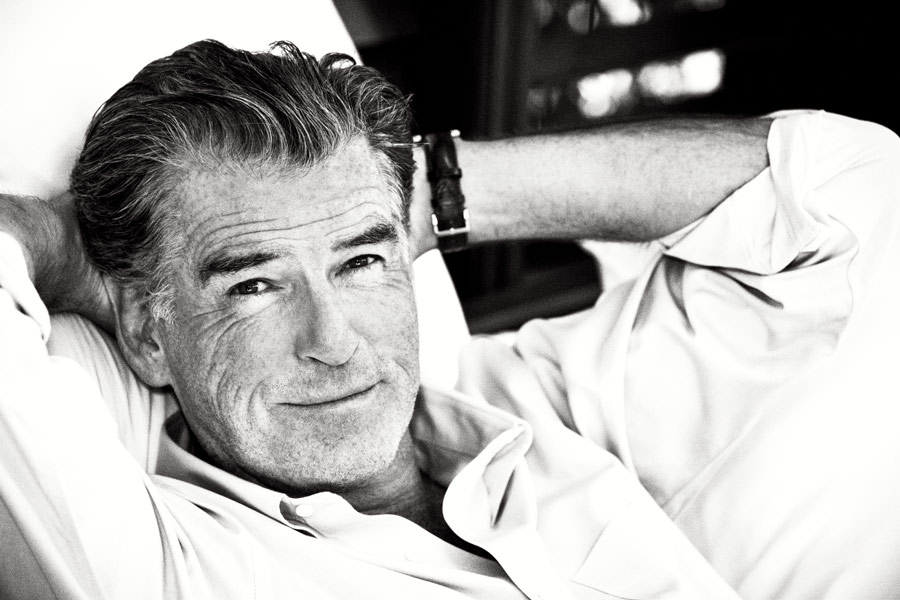

Breaking His Bonds: Pierce Brosnan

Originally featured by Tom Chamberlin in Issue 59 of The Rake, Pierce Brosnan says he wants a few more swings of the bat — to ‘shut them up’. What is there to do but stand back and watch?

They say that mighty oaks from little acorns grow. Unfortunately, the world today seems determined to convince us of the opposite, that those in positions of power demean those positions through their behaviour, showing all the tactful aplomb of my one-and-a-half-year-old facing down broccoli. The stories that back up this old maxim can embolden even the most afraid, determine the hopeless, and unveil courage where it is least likely to be found. The capacity to inspire is one that leads to glorious buildings, to gallant victories, and will provoke change in even the most entrenched thinking.

Cutting to the chase, Pierce Brosnan is an oaken hero, but not exactly in the way you’d think. Perhaps playing James Bond is enough, certainly

for anyone born in the

eighties, well into puberty, testosterone-fuelled

teenagers heading to see

GoldenEye, watching a man

throw himself off a dam,

punch that man on the loo, or straighten his tie at the end of a tank chase: it is stuff of the most stirring braggadocio. Yet it is the story of the actor himself that is proof we can will ourselves to become what we want to become, and that, under the right circumstances, the world is there for the taking.

Brosnan’s journey began not as a budding actor but as an aspiring painter. He says: “I left school with nothing but a cardboard folder of drawings and paintings, and that humble homemade folder was a passport to where I am now in life: I was 16 with zip qualifications and the knowledge that I had zip qualifications, but I had a burning passion to be an artist.” His talent for painting is evidently embedded in his bones, our photoshoot with the maestro Ellen von Unwerth giving us a glimpse of some of his works. A portrait he did of Bob Dylan sold at the amfAR gala this year for $1.4 million.

His ambition took him from his home country of Ireland to London, where for two years at the Ravenna Studios in Putney, a studio that has produced illustrators such as George Gale, he made the tea and drew straight lines and “watered the spider plants and did that repetitively and happily so because I was being an artist”. The political significance of a young Irishman moving to London at the opening acts of the Troubles is profound, and underlines the risk he had taken in the first place to get where he wanted to be. Fulfilled artistic needs aside, there is a sense from talking to Pierce that there was always a more ambitious, certainly more glamorous and high-profile, horizon about which he had his eyes on. A love of the movies planted a celluloid seed that was inevitably going to germinate. “Once I saw Bonnie and Clyde, that was it, I wanted to be up on the silver screen,” he says. “I had seen other people but somehow that captured my imagination.” One day, while on the topic of movies with a photographer at Ravenna Studios, it was suggested to him that a trip to the Oval House theatre (now Ovalhouse) in Kennington, south London, might set him on the path he would hanker for. “I walked through those blue doors on a winter’s evening and did a workshop,” he says. “It was the late sixties, run by Peter Oliver and Joan Oliver. They were my first mentors. It was an exhilarating, intoxicating place for me to find sanctuary and refuge. I was with like-minded, young, crazy misfits, artists, egotists, but all really passionate and gloriously experimental.” He soon found a taste for the medium and realised that if he was to make a go of it, he had to train, which took him to London’s Drama Centre.

Like many actors trained in the U.K., the theatre is the first port of call, the first love. The stage is entirely different from movie preparation and performance, but tutelage in theatre bestows upon the pupil a confidence and discipline and deep knowledge of the great writers and practitioners of acting folklore. “I left drama school with great confidence,” Brosnan says. “I was celebrated by my tutors and the work I had done, so I felt a great strength and burning ambition, laser-focused to go forth, to go to the Bristol Old Vic, to go to the Royal Court and do new plays, to go to the National, to be in great productions by the BBC, to do the best television, to maybe get a T.V. series and maybe a movie along the way. My ambition was manifold and I knew I had a certain look and a style and I enhanced that to the best of my ability with constant and rigorous reading of the greats and trying to make a living.”

Pierce had found a home, a home that was lacking in Ireland, a home that gave him a tribe he had always sought and an education that held his attention. “I just loved that I loved doing it, and I loved that I wanted to do it. The possibilities that I could be an actor filled me with the greatest romantic joy, and the possibility of making a living out of it, and because of having been short-changed with my education, it was also a day-to-day discourse with myself and finding literature that had meaning to me. Discovering Jean-Paul Sartre, Chekhov, writers that filled me with meaning to my own life. I just clung on to all of that with the greatest of willpower and a love of the movies. Going to the theatre for the first time was a religious experience. Having been brought up as a young Catholic boy serving mass, to sit in the theatre for the first time… It was the Royal Court theatre, it was a production by the Freehold theatre company, Antigone. I had no idea who Antigone was or anything to do with the Greeks, but that night, sitting in the theatre, is something I cherish and hold close.

“The training at Drama Centre instilled in me the profound love for acting and respect for the art, and the writer, and that one is going to hopefully do this for the rest of one’s life. It is life or death any time you walk on stage. To be a good actor you had to walk on and play the servant or walk on and play the king, you had to fill the space, and it was constant work in progress.”

His marketability was apparent to everyone, including himself, it seems. He knew which niche he could place himself in. “I wanted to be a commercial actor with some longevity, I wanted the world of Warren Beatty, Cary Grant, Steve McQueen, leading-man romantic hero; yes, I had all those emblems in my head. The movies — I thought this would never come to pass, or living here in America, but I guess there was a deep wish and desire beneath my workmanlike attitude for the job.”

While his early career didn’t register the kind of memorable roles he would later have — the exceptions being the rather unfairly maligned new squeeze in Mrs. Doubtfire and his brutal yet uncredited debut feature-film turn as an IRA assassin in The Long Good Friday — he had plenty of work. He was clocking up his 10,000 hours and building a reputation for himself, which, in time, as we all know, would pay off. The impression he gives leads you to believe that there was happiness in just being able to work, and while he was always ambitious, he revelled in the work, whatever form it took. “As much as I loved the romanticism of doing movies, the practicality was that I wanted to be a working actor and I wanted to work and build a career, I wanted to have greatness, or moments close to greatness.”

Greatness came his way when he was cast as James Bond in GoldenEye. They were troubling times for the franchise: Timothy Dalton’s exit after just two performances as Bond and a feud between the studio and producer that dragged on were perhaps the very least of it. The arrival of Brosnan was supposed to signal a push of the reset button, and boy did it deliver. Effortlessly suave, ostentatiously handsome, constantly sotto voce (which is almost certainly down to the musicality of his Irish accent): these were all impervious to the slightly out of date Soviet-bad-guy inflection of the plot, six years after the fall of the Berlin Wall. In fact, that reinvigoration of the old rivalry made perfect sense in the context of the Bond canon. Personally, it was a world he had fallen in love with from a young age. “Sean [Connery] was my James Bond at the age of 11,” Pierce says. “Goldfinger — it was indelible. Little did I know that I was going to enter into this world myself a few decades later.”

His 007 is the last of the caricatured, droll, insouciant, debonair vintage that handled killing with an overt irreverence and wit. His action scenes captured that ‘panther-like’ movement that made Cubby Broccoli cast Connery in Dr. No, and the innuendo-driven irreverence was redolent of Roger Moore. Brosnan was open about his approach of taking the best from his iconic predecessors. “Roger was very much part of my homage; so was Sean. My Bond was a blend of Sean, Roger and myself. I dabbled in some of the other books and then I focused on what words were on the page and let my own imagination do the rest. There had to be humour, I felt. The movie had been dormant for six years, so I knew that I was walking into a house that had been locked up and there were many questions, of ‘do we really need another James Bond?’.

“The press conference I did for GoldenEye I will never forget. It was a baptism by fire. But then you have to sit quietly with the script, and if it is well written and you can believe in it then you find your own Bond in toughness and style. I wanted him to be as human as possible because he was so fantastical on the screen.”

His Bond contrasts greatly with the current incarnation of MI6’s finest, the slightly more obstreperous Daniel Craig version, which verges into a much more ferocious, less humorous and more psychologically introspective manner than any of his forebears. As far as Pierce is concerned, it is a move purely to resonate with, and meet the demands of, a different and evolving audience. He says: “It is different. I remember going to see The Bourne Identity. I knew there had been a seismic shift, and little did I know I was going to be a part of that seismic shift in the curtain falling on my contract. I was employed for four [Bond movies]. When that happened I knew they had to make adjustments, and it was impressive to see that work and see that character of Bourne in the hands of [director Paul] Greengrass. That is my take on it: they had strong competition and they haven’t reinvented it but given it a much more muscular, dynamic twist. There’s not much humour. When I played him you have to let the audience in that this is a fantastic joke, this man, what I am doing here, jumping off a motorcycle and catching up to a plane is completely preposterous, but for me you had to let them in, and that’s what I was brought up with. Sean did it, Roger did it par excellence — I think he never had faith in himself as an actor so he just camped it up. He had the most beautiful self-deprecating humour. He knew he couldn’t do what Sean Connery did, but Sean can’t do what Roger did. You have to trust your own style and you have to have deep faith in yourself and humility and grace under pressure to pull it off — or at least attempt to do it.”

Perhaps he is right that the elements of humour have been skimmed off in the face of demand for heavier-hitting action. It is certainly the case that the ‘joke’ about which he speaks has been a little forgotten — the ludicrous scenarios that Bond found his way out of through gadgetry or well-worded rebuttal is now the world of ball-busting torture and rather dark psychoanalysis. There are some who say that actually it was Fleming who dictated the latter, as he did seem to indicate Bond’s inner demons in his books — from flashbacks caused by seeing the Cyrillic carved into his hand by an enemy spy to heavy drinking alone in New York hotels. Whatever the purpose, and the competition argument is a compelling one, Brosnan’s 007 was the fulcrum, and opinion is divided as to which side you fall on as a Bond fan.

During this time, Pierce had gathered enough contacts and enough energy to broaden his creative horizons, and he set up a production company with a friend, Beau Marie St. Clair, which would be the source of much of his filmic output. The company, called Irish DreamTime, started over lunch. “I was sitting with my friend Beau Marie, and her boyfriend always said that the two of us should get together and produce, and on this particular day he said it one too many times. I said, ‘Give me a quarter’ and I called [studio executive] John Calley, who said let’s meet next Tuesday. Beau and I formed Irish DreamTime. And the first film we did was a film called The Nephew with Donal McCann.”

You’d think the pressure of playing one iconic role already played by an iconic actor might be enough for a lifetime, which is why Brosnan’s decision to take on The Thomas Crown Affair may have seemed like he was a glutton for punishment, especially as it was being done on his own dime with Irish DreamTime. He says of the decision: “I knew I was going to be tagged forever as James Bond, and that’s fine. I welcomed it all because you feel very protective towards the character, you want the best for the character and you don’t want to do anything that upsets that within the proscenium arch and the contract of four movies. I didn’t want to go off and do something completely off the beam, you want to bring the audience with you.” Retrospectively, it feels like all his projects begin to make sense with this train of thought.

As for why that character in particular (one that his brilliant publicist tells me was a character very much like the real man), Pierce’s justification is clear. “Once I realised that I hadn’t made a complete pig’s ear of Bond, there seemed to be momentum to play the role [of Thomas Crown]. Steve McQueen was very influential in my life, being cool, wanting to be cool, and we hit on the notion of Thomas Crown because I could get my toe in the door — it was MGM, they had it on the shelf, I loved Steve McQueen, I loved the Windmills of your Mind, and that was it, it was a good fit. John McTiernan [the director] was an old friend. I had made his first film, Nomads, we had a great script, I went to him with this gift and that’s how it happened, really. I remember my wife was thrilled to be back in New York, our little boy loved it, and I just had mild panic attacks with the idea of doing Steve McQueen: how do you do cool? Crown holds great alchemy for many reasons and we got away with it, and it fit well under the umbrella of Bond.”

Funnily enough, his first encounter with a spy was not for the purpose of researching Bond, but for his 2001 exotic location romp The Tailor of Panama, in which he plays a similar character to Bond, albeit a more obsequious version. “I thought they were offering me the role of the tailor. It wasn’t till my second mouthful of carbonara that John Boorman [the director] said, ‘No, no, you’re playing the spy.’ So I wanted to meet someone from MI5, and after much toing and froing I got to meet the head of MI5 and it was at the bar of the Connaught hotel in London. He had a cold, I remember. So for some reason I wanted to do that research for The Tailor of Panama and not James Bond. I also met with David Cornwell [John le Carré]. He and I met at a golf course and walked the golf course and he spoke of his days at university and how they stole his youth, and the work of being a spy, a rather pastoral lifestyle, being in Hong Kong and getting to know the hotel managers, bank managers. He was the one really who helped me enormously.”

The following year saw the release of his final Bond film, Die Another Day, the one with all the ice. The danger of playing Bond is that you can find yourself short of work, as people only ever see you as the character and never the potential for anything else. “I had seen men go down this road before,” Brosnan says. “Particularly Sean. I had a great admiration for Sean, his presence on screen and that he was a Celt — my stepfather was Scots — so I had a kinship with him as an audience member, and likewise Roger, because growing up in Ireland in the sixties I adored The Saint. I wanted to have the same hairstyle as Roger Moore. Got to have good hair, a good hair performance. I think we all want to be cool, I think we like to be cool. At the end of the day sincerity is the best road to go, be good to yourself and trust yourself and know yourself, and if you don’t have anything to say, don’t say anything, just listen. And that goes for acting; listening is the hardest. I certainly knew going into James Bond that if I was any good at it — and I wanted to be great at Bond because I loved the character so much, that I was an Irishman playing an Englishman, an Irish James Bond, I thought that was so mighty, such a validation for many reasons — that I also had to have a career afterwards.” While the Pierce Brosnan brand of Bond may have expired, the Pierce Brosnan brand still lives and thrives. “I wanted to have a career after Bond. I knew I wasn’t going to please everyone with my James Bond, that is the nature of the game, but I did want to have a career and I wanted to know how to make movies, to have my own pocket full of dreams.”

Irish DreamTime kept Brosnan busy. The Matador was an accidental success, in that Richard Shepherd, the director of said film, initially submitted the script a writing sample, a writing audition if you will, for The Thomas Crown Affair 2 (which never happened). It began to confirm Brosnan’s post-Bond era was going to be as exciting as before. As our founder, Wei Koh, says in his opening letter, there is much to be said for men who, in their sixties (Brosnan is a cool 65), have become their essential selves. For example, Brosnan’s beard growth and rugged get-up in the western drama The Son added a less clean-cut but more badass side to his work. Same, too, when he plays Liam Hennessy, the politician with blood on his hands in 2017’s The Foreigner alongside fellow sexagenarian Jackie Chan.

And, of course, there is Mamma Mia!, the 2008 colossus, a rip-roaring success with the whimsical eighties soundtrack and Hellenic backdrop, adapted from the highly acclaimed stage production. In it, Pierce plays the suave sophisticate, but he comprehensively pulls himself out of any pigeonhole people had placed him in. Unsurprisingly, its $615 million dollars at the box office meant a sequel was inevitable, which brings us to last month’s release of Mamma Mia! Here We Go Again. “I was over the moon that they decided to do another and we were all brought back together again,” Pierce says. “It is definitely one of the most joyous films I’ve ever been a part of and the success that it had was beyond my wildest dreams and I think everyone else’s.

“I think each and every one of us were thrilled to be in the company of one another again, singing, dancing to the best of one’s ability. Funnily enough, I didn’t sing as much in this one, I don’t know why… Lily James is so radiant, they all are, this young cast, they all give of themselves in the most generous of fashions, the most impeccable timing and alacrity of thought, and then you have the legacy cast, Colin [Firth], Stellan [Skarsgard], myself, Julie Walters, Christine Baranski, and beautiful Amanda [Seyfried] leading it all, and then there’s Meryl [Streep], Cher, Andy Garcia, it will be great.”

As a parting shot, Pierce paid homage to those closest to him whom he regards as responsible for his success and the importance of them in his life, namely the women who have been with him on the journey. “I have been blessed in life with meeting wonderful women. My first wife, Cassie, we had a glorious 17 years of life and she was the one that said we should go to America — I would never have done it by myself even though I had this burning ambition, I probably would have just plodded along and been very happy, but she was the one who said we should go to America, so I do have to tip my hat to her. Likewise to Keely [Shaye Smith] now, after 25 years of partnership and building homes and family, she is very important to me. I like the strength and friendship of a good marriage, and a good wife, you know, plodding and scheming your way through it all. Creating Irish DreamTime, making movies with my friend Beau, just making movies, being able to get away with it was so gratifying and deeply meaningful. It was about friendship, she [Beau, who died in 2016] was a good woman, a great producer. Again, blessings of great women in your life — takes a wise man to know that; they are just smarter than us, they have to be.”

His high regard for others is reflected back on to him. His co-stars in Mamma Mia! giving The Rake the benefit of time spent working with him, namely Lily James and Colin Firth.

What of himself, reflecting on a career that is long but far from over. How does his musically articulate way of describing others come to bear on himself? “I don’t really know how I am viewed but I know I am still at the table and working as an actor. I want a few more swings of the bat that shuts them up, fucks the begrudgers.” If there’s one thing that most people with even the most casual ear to the ground can say for certain, it is that he has already done so, with the greatest aplomb, under the most unlikely circumstances. He has emerged a hero to us, very much of the non-fiction variety.