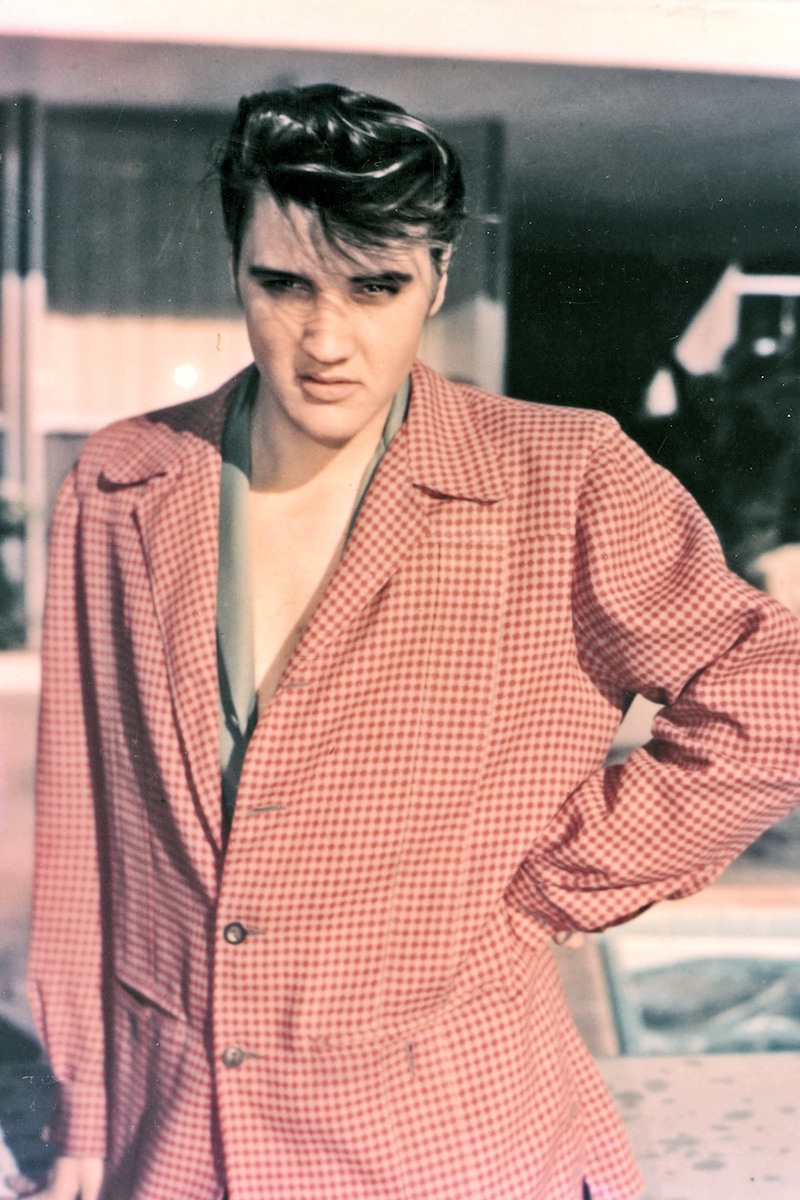

Elvis Presley: The Breakthrough Moment

G. Bruce Boyer recounts the pivotal moment of The King's journey to super stardom, when, as a swaggering, confident and deviously handsome 19-year-old, he walked into Sun Records studio...

There’s a point to be made about Elvis Presley’s early life that actually touches on our music in a unique way. Forget the bloated, drug-addled, gun-toting, ludicrously dressed Elvis of his later years, the horror figure that haunted Las Vegas singing to middle-aged women and passing out his sweat-drenched cheap scarves. I’m talking about the shiny young man who walked into the Sun Records studio in the morning of his life full of hope and confusion, with charisma and talent bursting transcendently out of him.

Elvis came of age in the very middle of the 20th century, in the decade following two world wars and a soul-searing economic depression. And it was for the post-war American 1950s to delve chaotically into the issues of race, working-class anxiety, mass culture, corporate consumerism, and sexual permissiveness in a time of unparalleled and prosperity. When it came to the New Music of youth, rock ’n’ roll, it was clear to everyone from the beginning — fans and detractors alike — that Presley was a catalyst, that he straddled both black and white entertainment, and that his story was a uniquely American story: the poor southern boy who became a significant cultural icon of the century. As Bob Dylan later said, “Hearing him for the first time was like bursting out of jail”.

Those first few records he recorded at the Sun recording studio on Union Avenue in Memphis shined forth the promise of a new dawn, a new and vibrant world possessed by the spirit of joy and the hope of plenty. But to listen to the historic Elvis Presley Sun sessions today is to feel nothing so much as a great sadness, a sadness of waste and indulgence and exploitation, a gloom in which to contemplate what might have been instead of what was: the erratic but understandable downward spiral into drug addiction and death on a bathroom floor at 42, distended and destroyed by success.

There was so much promise, so much exuberance in those first songs — a mere 19 of them — recorded in the months from July 5, 1954 to July 11, 1955. The actual recording dates of specific songs during this period are not known, so there’s considerable debate among critics, but everyone seems to agree that Harbor Lights was the first recording to have survived, and Tryin’ to Get to You and Mystery Train the last. We think, looking back over the trajectory of Elvis’s fame, that perhaps what followed was all but inevitable — even predictable — as success corroded and finally destroyed a budding talent who might have achieved so much more than just celebrity. He might have been an artist.

After Sam Phillips, the entrepreneur and owner of Sun Records, formally sold Presley’s contract in November of 1955 to RCA Victor, it was almost all downhill from there. The second half of his short life reflected unprecedented celebrity, wealth, blind adulation, and a few more interesting songs. No films — and there were 30 of them in his 13-year movie career — were worthy of the promise of his youth, although there’s reason to suspect he might have become a fine actor. Presley never even performed a concert date outside the U.S. The sad truth, even though we didn’t know it at the time, is that by 1958, when he was inducted into the U.S. Army, his beauty and his creativity were behind him. A few brief echoing rays of the glory that had been might suddenly shine through, yet the sun had all but set.

He was apparently fluent in most of the great tumbling vernacular of American popular music of every stripe.

None of this is revelatory, and many music lovers and critics feel, as I do, that Presley’s talent was exploited shamelessly, ruthlessly, and that he was unable, perhaps incapable, of withstanding the pressures of undreamt success and the forces of misuse he seems to have mistaken for guidance. Who would be able to withstand it? Undoubtedly most of us would be equally unprepared at that age. Pretty much a tragedy, pure if not simple. A tragedy deepened by the knowledge that when he walked into the Sun studio, a raw, swaggering 19-year old, he had a great untried talent, a new vision and a ton of charisma. Just as importantly, he had almost unaccountably already accumulated an incredible amount of musical interests and knowledge. Apart from the untrained beauty and unique style of those early vocals, what is of such interest in perusing the repertoire of the Sun Sessions is the surprising variety of musical genres familiar to Presley. And, in the rock critic Nick Tosches’s wonderful turn of phrase, he had “no restraining concept of commercialism” about him yet. It’s a word not easily used with Elvis, but he was pure.

He was apparently fluent in most of the great tumbling vernacular of American popular music of every stripe. Chicago and southern blues, standards from the American songbook, folk tunes, bluegrass, country and western, boogie-woogie, jazz and more. In those early sessions (historians of the music are generally agreed there were a total of seven) he recorded songs that had been done by Arthur ‘Big Boy’ Crudup, Bill Monroe, Junior Parker, Eddy Arnold, Roy Brown, Jimmy Wakely, Kokomo Arnold and Charlie Feathers. That first song committed by Presley to recorded immortality, the oft-done sentimental standard Harbor Lights, was first recorded in 1937 by Frances Langford as a Big Band ballad (and then by virtually every other pop ballad singer of the Big Band era), and the last, Mystery Train, was Junior Parker’s rocking up-tempo classic. Such an incredible number of influences.

But where had he heard all this music, this disjointed mix of genres and sensibilities, of sounds and rhythms, of tastes and forms? This is an area worthy of investigation, because all we are left with is the evidence of how he intended to bend this material to his own personality and style in those iridescent seven sessions on Union Avenue in the early fifties. How had he accumulated this catalogue of musical Americana, and how had he thought about these disparate sounds from so many different streams of American music? Whom had he imitated and re-worked, what little gimmicks had appealed to him and from whom had they come? How had he synthesised them into his collective aesthetic, an aesthetic that would characterise and define the new sound of young American music called rock ’n’ roll? Perhaps more importantly, how is it that he seems to have made no distinctions, no value judgments, about these disparate genres other than the classic one made years before by the great Duke Ellington: “Music is music, it’s either good or bad.” He seems to have been a non-judgmental receptor of the culture available to him. It was an American story.

It’s rather astounding when you think about it. Elvis seems to have simply taken what he liked from wherever he heard it. No prejudices, no partisanship, no preconceptions. Just a finely tuned ear for joyous sounds. No wonder he was so thrilling to the young, so threatening to conformity, so much at the head of change and faced towards the future. The answer must be that he simply must have listened to everything available to him at the time from the street, records, and radio with an open mind, had an intuitive ear for great sounds and considerable interpretive sensibilities, and knew what to do with these songs to make them his own. How else is it explainable?

He was the New Man of the New Age come to vex and unsettle the corporate conformity of the Eisenhower 1950s. Adults didn’t quite know what to make of it, and so they worried. Jazz, of course, had worked exactly this way, up from the ground of creativity, from the streets and juke joints and nightclubs and brothels, and taken its inspiration from anywhere and everywhere. Presley was firmly in this tradition of blues-based music from the Mississippi Delta, as well as the gospel music he heard and sang as a child in his Assembly of God church in Tupelo, Mississippi. But that was part of the jazz story, too, and became mixed in with popular songs from the radio, local saloons, and travelling shows. That’s how America worked when it came to creative popular music.

Elvis seems to have simply taken what he liked from wherever he heard it. No prejudices, no partisanship, no preconceptions. Just a finely tuned ear for joyous sounds.

With every recording session after he left Sun, he drifted more and was pulled further and further from his roots. His manager, Col. Tom Parker, can probably can be held responsible for destroying the relationship he had with Sam Philips, as well as moving him towards Hollywood and away from his roots. The legacy is now so tarnished, so awash in shoddy stardom, so sadly saturated with unwholesome indulgences, so tainted with greed and patinated with glitzy commercialisation. But the way to purge ourselves of this toxic cultural pollution is to remember how it started and what it had meant. After all the achingly mediocre and embarrassing films, the Las Vegas rhinestone stage shtick, the downward stagger into obesity and drugs, parapsychology, isolation and craziness, can we try not to forget a time when a handsome, charismatic young man with a soul full of music walked into a small independent Memphis recording studio in the middle of the 20th century and gave us a glimpse of a future more scintillating than anything we could have ever imagined? A great democratisation of music took place that was so unselfconscious, uncommercialised and pure. That the dream was never realised by the dreamer, that the promise was never kept to those who heard those early recordings, takes not one note from the joy.

Discography reference:

Elvis Presley, Elvis at Sun, BMG Music, 2004.