Rakish Icons: Patrick Lichfield

Originally published in Issue 45 of The Rake, James Medd writes that he was the working-class aristocrat who became a self-made man with the help of his blue-blood friends. But Patrick Lichfield, the dandy with a bouffant hairdo, had a gift for connecting with people, and he used it to great effect to create photographs that still resonate today.

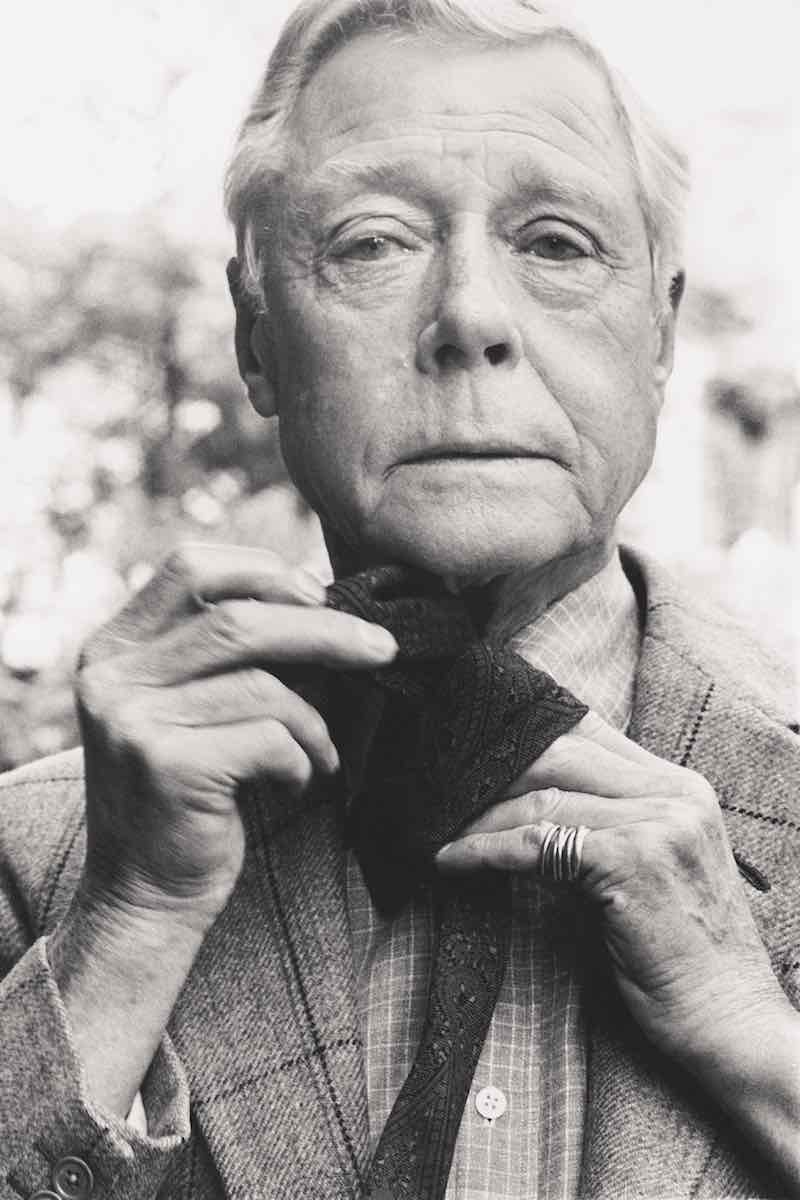

Patrick Lichfield, or the 5th Earl of Lichfield, or just Lichfield, was, like Churchill’s view of pre-war Russia, a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma. How could the royal family’s in-house photographer, the King’s Road dandy and the assiduous objectifier of the female form be one and the same man? With his permanent Cheshire-cat grin, shirt at half-mast, and bouffant hair, he was a tireless worker, shameless self-promoter and something of a hack — even, for all the breeding, a bit of a wideboy. Look, however, at a careful selection of his many photographs — Talitha Getty turned on and dropped out on a roof in Marrakech in 1969; Prince Charles rushing to embrace Lady Sarah Chatto (then Armstrong-Jones); Mick and Bianca Jagger as the just-married king and queen of the new decadence in 1971; the Duke of Windsor getting himself ready — and you find images that still resonate and surprise. The same is true of his royal portraits: who else, after all, caught the Queen smiling as often as the sly Lichfield did?

If he was unappreciated, it was perhaps because he didn’t always take photographs like these, the kind that win prizes. As he told one interviewer in 1971: “I have spent time photographing down-and-out drunks in east London drinking meths, but given a choice I prefer to take romantic photographs.” Easy to forget that he was one of the key chroniclers of the 1960s, both in formal line-ups arranged for Queen magazine featuring Tom Courtenay, Twiggy and Joe Orton, and in his portraits of the era’s bright and beautiful, from George Best to Jane Birkin. Often the fact that this committed socialite was as much participant as observer didn’t matter; at other times, as when he was able to capture the newlywed Jaggers in the back of a Bentley, it did. Here, he was not the photographer but the friend who had given away the bride; through him, we are not just in the car and in the moment but one of the party.

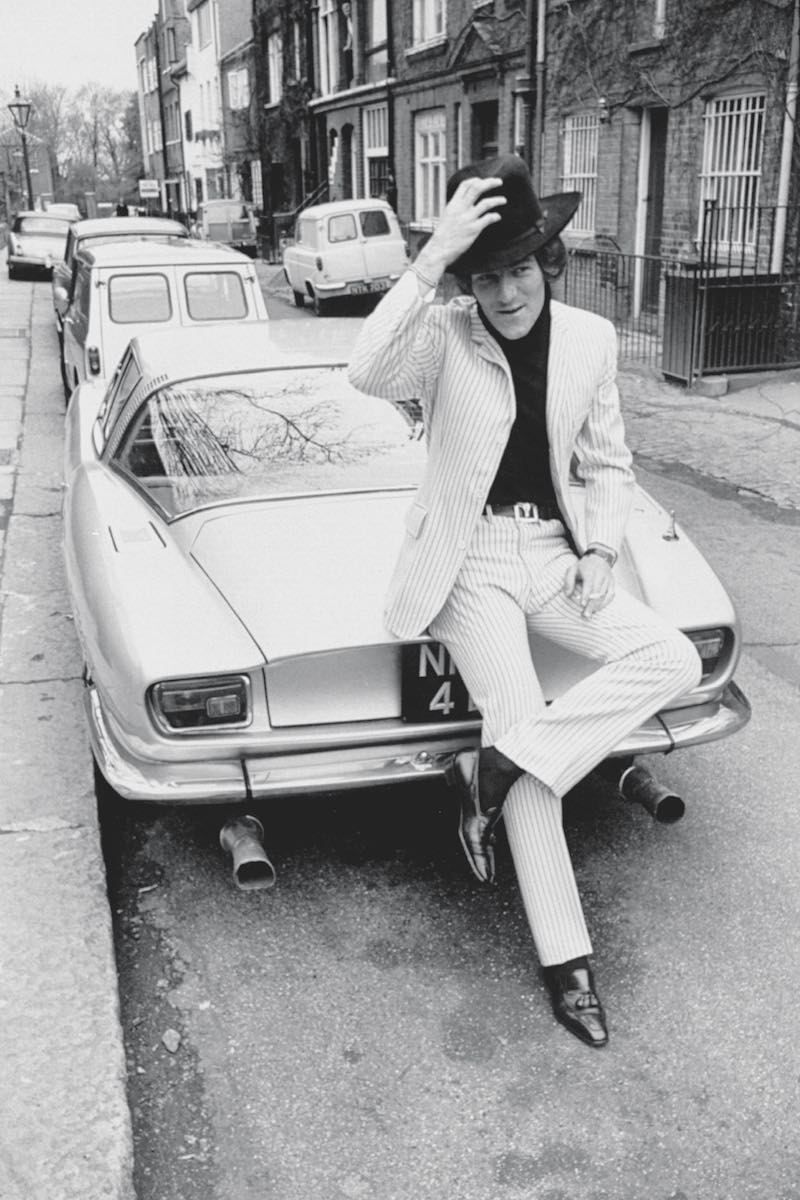

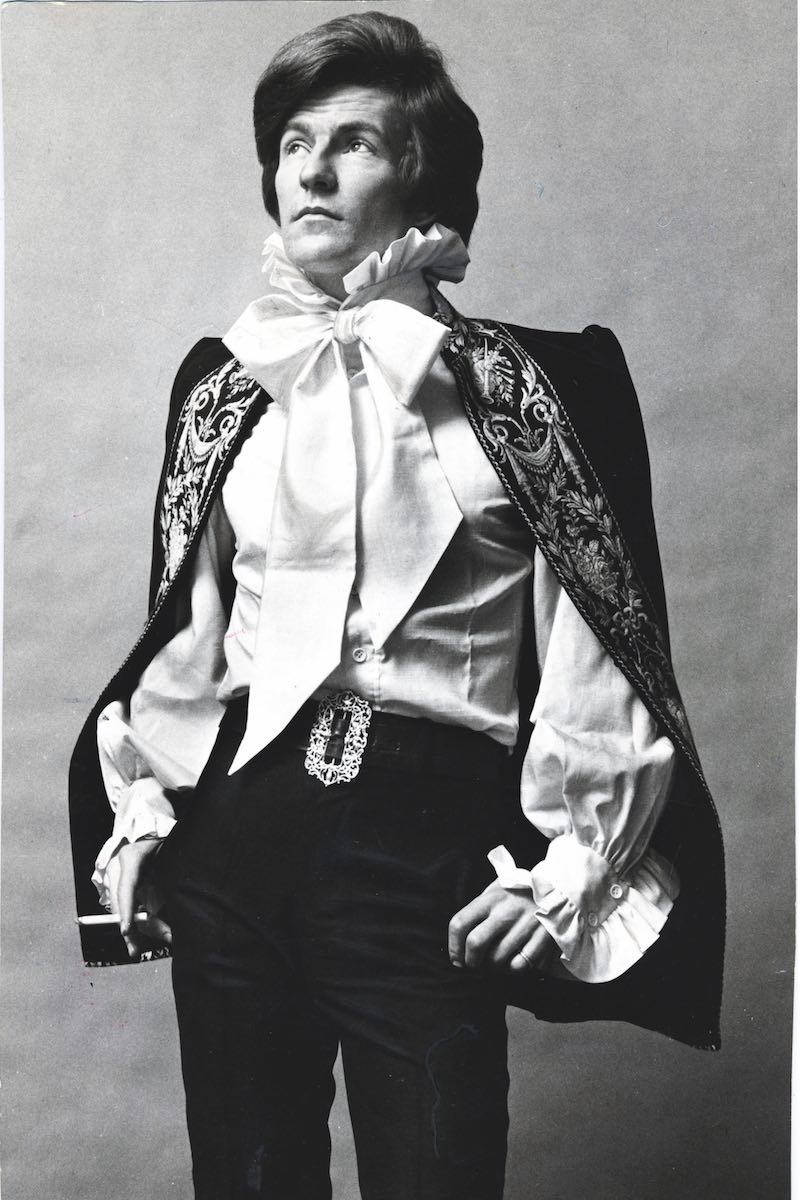

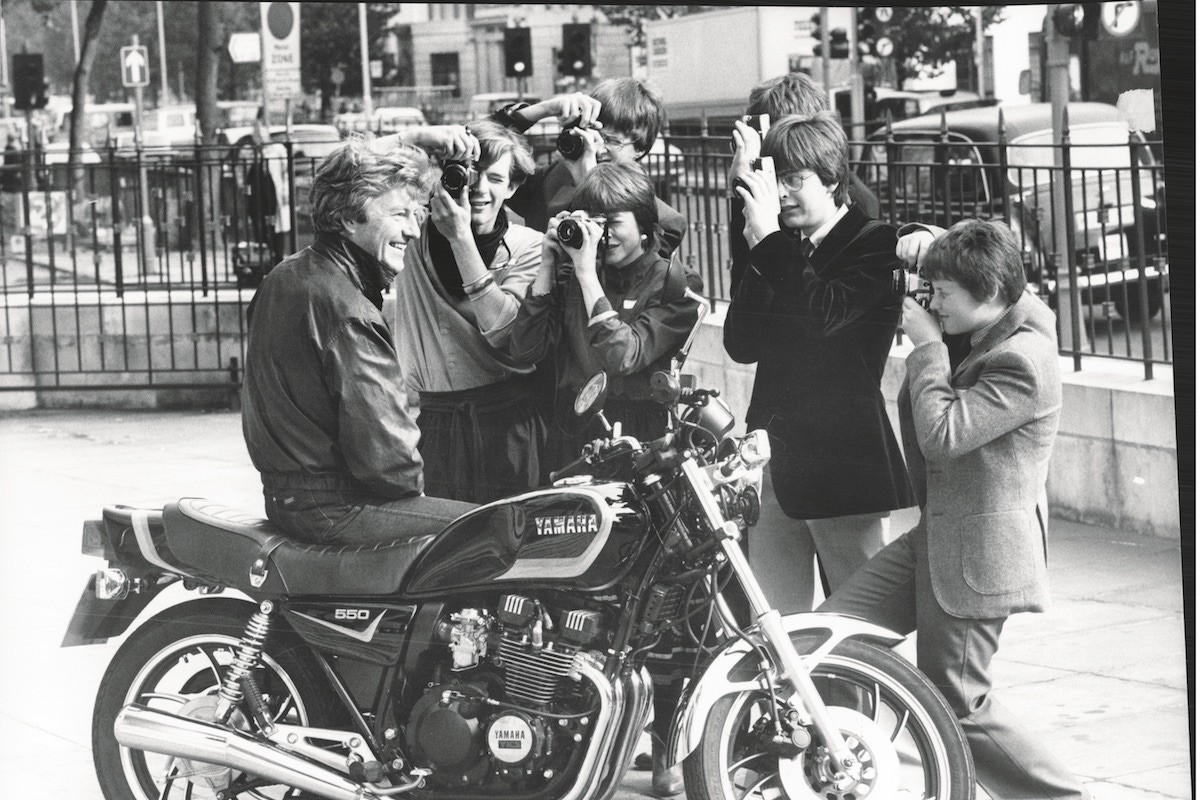

Usually, Lichfield was too busy working or enjoying himself to worry about art. If anyone was about to take his work seriously, a glance at the man himself ensured they thought twice about it. Even for the bewildering modes of the seventies, his attachment to the professional blow-dry was unusual for any male outside the fields of pop stardom or professional football, and his tattoo (a seahorse on the right forearm, performed as payback by a tattooist whose picture he was taking) was equally unconventional. At that time he paired them with cowboy boots and motorbikes, and, with his Eaton Square apartment, country house and mansion on Mustique, lived a life that was already a rock-star cliché. Fitting in while standing out was one of his great skills. In the decade before, it was cloaks and ruffles from Mr Fish, his exuberance ensuring he was better known as a follower of fashion than as a photographer.

One sixties contemporary described him as looking “like a silent-film Scarlet Pimpernel”, but if Lichfield had a tendency to overdo, it was down to enthusiasm rather than vanity. Fop though he was, he nonetheless paid his dues with three years as a photographer’s assistant, sleeping in the studio and scraping by like any other. His professional name, Patrick Lichfield, was an attempt to disguise his origins: “The heterosexual, cockney working-class lad was the image of the time,” he later explained, “whereas the privileged toff as personified by Beaton had had its day.”

Born Thomas Patrick John Anson in 1939, grandson of the fourth Earl and related to the Queen Mother through his maternal grandmother, he played the game for long enough. After Harrow he went to Sandhurst, then joined the Grenadier Guards, but had already set the course of his later career when he underbid the school photographer to win a contract for the leavers’ pictures, taken with his small Kodak. Succeeding to his title at 21, he found that his grandfather had sold most of the estate, Shugborough Hall in Staffordshire, to the National Trust, freeing him of his hereditary responsibilities whether he liked it or not. He profited from the sixties revolution as much as working-class colleagues such as David Bailey or Terry O’Neill.

Still, he didn’t avoid his regal relatives for long. He began capturing them on film from 1966, went on board the Royal Yacht Britannia for cousin Elizabeth’s silver jubilee in 1977, and, edging out fellow semi-royal Lord Snowdon, was official photographer at the wedding of Prince Charles and Lady Diana Spencer in 1981. Having one of the family behind the camera certainly helped relax the crowned heads, but so too did his natural confidence — what might otherwise be described as a sense of entitlement. Never fazed by the wealth or fame or self-importance of his subjects, he found it easy to control large groups, usually up a ladder with a whistle. It was this technique that gave him one of his most celebrated images of the Charles-Diana wedding, when a sudden blast had the entire party lit up.

Catching royalty off guard won him his big break, too, when he was sent by Diana Vreeland, editor of Vogue, to photograph the Duke and Duchess of Windsor in 1967. He secured the commission by giving her the correct answer to the question “Who is the best-dressed man in the world?” What won him a decade-long contract with Vogue, however, was falling through a chair in the Windsors’ garden, an act that lifted the sombre exiles to laughter, caught on film as he fell. His aspiration may have been romance, but levity was Lichfield’s trademark. It was conjured not only from royalty but also those who held a mask up to the world for other reasons, including film stars from Charlie Chaplin to Catherine Deneuve. Along with that aristocratic entitlement, it was charm that won him his greatest prizes. He was energetic, funny and fun, so that even fish as cold as Dirk Bogarde or, indeed, the Queen melted.

His charm was also directed at the many models and ingénue actresses that passed in front of his lens over the years, some of whom he stayed with for a while, notably Britt Ekland and Jane Seymour. Though of average height, rather too skinny, with bad skin and traditional English teeth, that inbred confidence made him much more than the sum of his parts. Women were an unusually keen interest, one that his succession of 17 calendars for Unipart, featuring barely clad models in a variety of exotic locations, allowed him to pursue with particular vigour during the 1980s. It doubtless hastened the end of his 10-year marriage to Leonora, daughter of the Duke of Westminster, whom he’d met when taking her portrait as the Debutante of the Year. She was not prepared to keep up with his constant travelling and unstoppable drive, which was unabated by the arrival of three children.

Yet he was more than charm and lust. His taste for the bohemian life of the sixties came with a keen commercial sense, leading him into businesses that ranged from clothes boutique Annacat to restaurants and property. He put money into hit sixties stage shows Hair and Oh! Calcutta!, the proceeds from which supposedly financed the house on Mustique. He saw these ventures much as he did the day job — a chance taken. “One must always keep playing hunches,” he said. “You don’t know every day that you are going to take a great photograph.”

The money enabled him to sustain four homes, as well as a transport fleet that might include a Jaguar, a Mercedes, two Jeeps and two motorbikes. It was one reason for the constant working, but not the only one. In later years he strived equally hard for others, including Voluntary Service Overseas and hospices near Shugborough. A new partner, Lady Annunziata Asquith, brought stability, but nothing slowed him down, barring a near-fatal fall from an 18-foot wall in Mustique in 1991.

At his core lay that riddle: what was the rush? Why the need to keep moving and working that meant he was unable to stay at Shugborough for more than four days or to go on holiday without taking his camera? Long before, Leonora had confided to a journalist, “I don’t know what he’s trying to prove to whom any more. When I ask I never really get a straight answer.” It’s unlikely that, when felled by a stroke at 66, he knew himself.

This article originally appeared in Issue 45 of The Rake.