The Real McKay

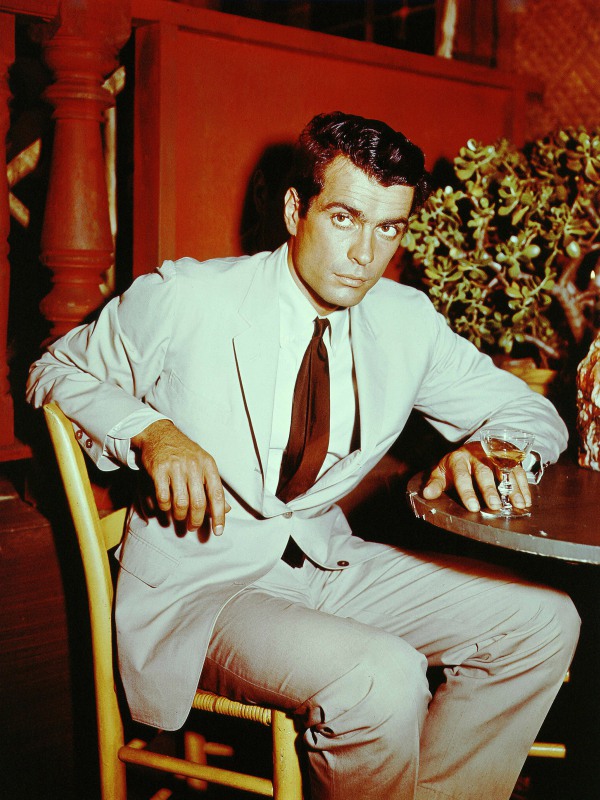

Gardner McKay was the antithesis of the fame-hungry ’sleb that contemporary culture knows so well. Originally published in Issue 58 of The Rake, Nick Scott writes that he spurned heartthrob status for a life of adventure, literary achievement and existential restlessness…

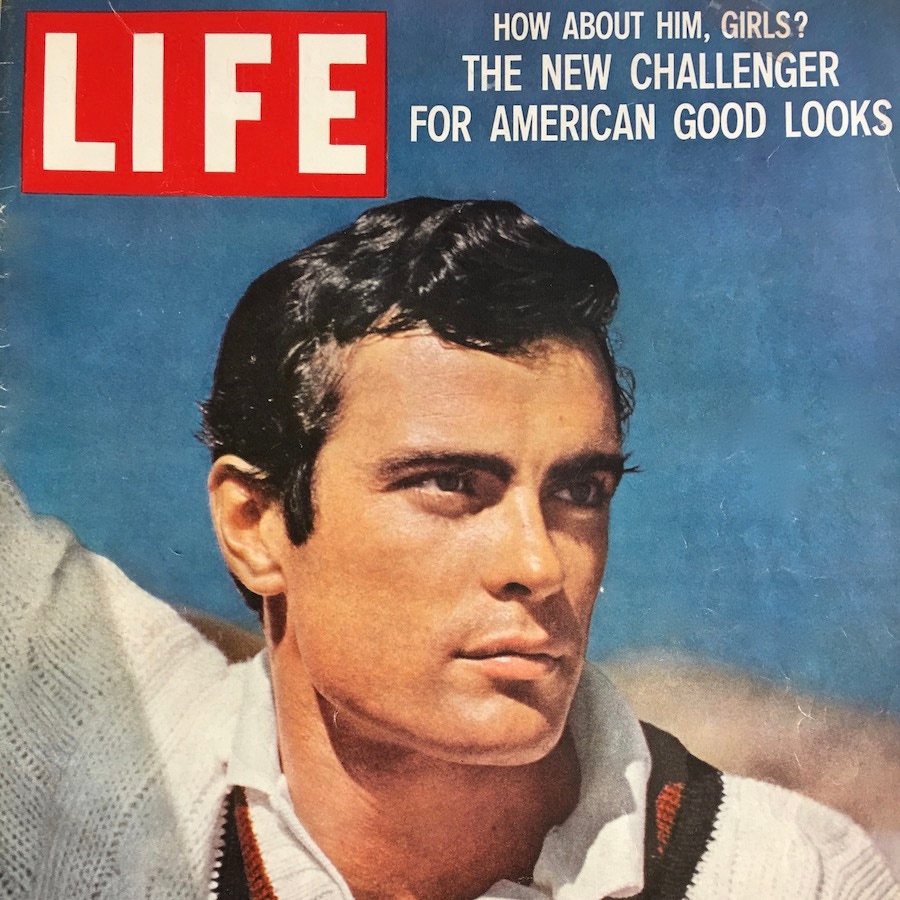

The issue of Life magazine that hit the newsstands on July 6, 1959 bore the image of an almost excruciatingly handsome man, then 27 years old, staring into the middle distance: dash-of-salt, tousled hair; lips puckered rakishly; eyes fixed in a gentle squint towards some unseen object of conquest (a cricketing nemesis’s middle stump, one might assume, given the raised right arm and cream V-neck sweater, were the man in question to hail from the other side of the Atlantic).

A strap at the bottom of the cover referred to this enigmatic Adonis as “actor, athlete, artist”, which now comes across as a rather cursory summary. Had the cover been published in the latter stages of Gardner McKay’s life, the magazine may have needed to accommodate other accomplishments, including sailor, basketball star, diver, fisherman, model, sculptor, theatre critic, photographer, and, improbably enough, agronomist’s assistant.

The cover line at the top of Life’s front page reads, “How about him, girls?”, and the feature inside exclaims: “This is the face that will launch a million sighs and burn its romantic image into the hearts of hordes of American females.” But while the girls would have been reaching for the smelling salts, it’s possible it was the boys in post-war America who felt more curious about the life of such a man. Indeed, when you get to turn down Marilyn Monroe’s personal appeals to become her co-star, and when your memories weave such a rich narrative that they scarcely seem plausible — as was the case with Gardner McKay’s unfinished Journey Without a Map, written as he succumbed to prostate cancer in 2001 at the age of 69 — you can relax in the knowledge that you’ve lived life to the full.

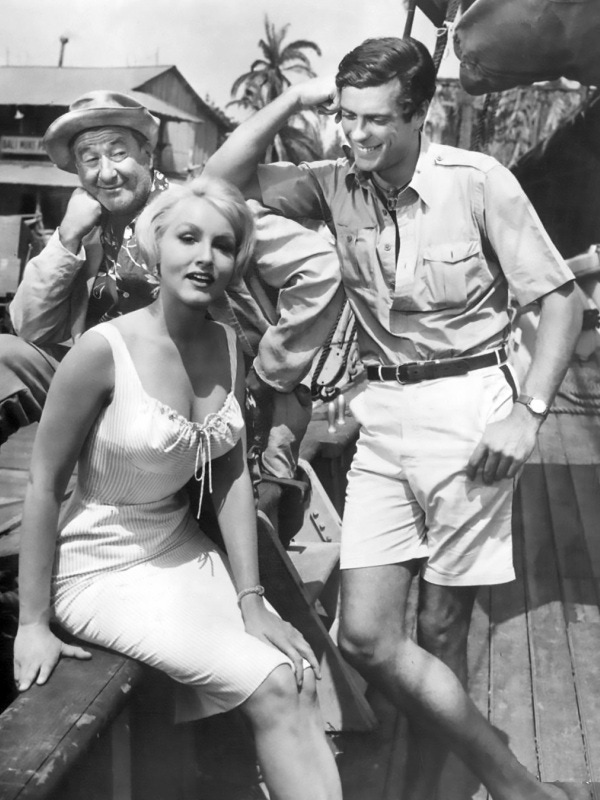

McKay became a household name thanks to his starring role in the television series Adventures in Paradise, based loosely on James Michener’s Pacific Ocean-based yarns, which ran from 1959 to 1962 and in which McKay starred as a skipper of a schooner that plied the South Pacific in search of improbable adventures. In a sane world, that show would be but a furtive, small-print disclosure on his CV. The great-grandson of the shipbuilder Donald McKay, McKay was born George Cadogan Gardner McKay into a wealthy Episcopalian family in New York City, but brought up between there and Paris (between the ages of four and 17 he crossed the Atlantic eight times and stayed in 13 different boarding schools).

He worked briefly as a sculptor during his studies at Cornell University, and also worked as a movie-critic for the Cornell Daily Sun and the campus magazine The Widow, plus various articles for yacht magazines. Moving back to New York, he took up sculpture (he had one piece displayed in the Museum of Modern Art) while living in modest bliss in Greenwich Village and enhancing his credentials as a polymath by doing extra work as a designer, artist, record covers illustrator and painter.

Then came a brush with the more peculiar extremities of chaos theory. Having been offered a modelling job in Paris in 1956, a series of photographs with the model Suzy Parker, McKay took a ship to Europe that encountered the stricken Italian ocean liner Andrea Doria, which had, in dense fog, been struck by the Swedish cruise liner M.S. Stockholm off the coast of Nantucket. Lesser mortals might have looked on in horror as 51 passengers went to a watery grave: McKay scrambled onto a lifeboat and took photographs of the sinking liner that ended up being published in The New York Times, Life and many other global titles.

It was in far more tranquil circumstances — he was minding his own business, reading poetry in a Hollywood coffee shop — that McKay was spotted by Adventures in Paradise co-producer Dominick Dunne, and invited to take a screen test. He’d already had small roles in feature movies Raintree Country and Holiday for Lovers, but this chance meeting would lead to television colouring the next chapter of his life.

“Gardner was a classy guy — good goods, as they used to say,” was how Dunne described his meeting with the six-foot-five McKay, and their serendipitous encounter (it helped that McKay could sail, having whiled away many a pleasant hour marshalling his own 19-footer sailing boat, China Boy, in the Long Island waters as a teenager) led to him taking the lead role.

It was his matinee-idol looks, rather than thespian prowess, that carried him through the gig: in an early review, one critic mentioned that McKay played his role “in one emotion”. But in his defence, his heart wasn’t in it, and his relationship with celebrity might best be described as unidirectional. Jean Doumanian, his film producer and friend, later said: “He hated the fact he was known for that television series. It was not the professional or private path he wanted to take.”

McKay was just as unequivocal on the matter: “Fame is so cheap that I wanted to go someplace where someone, some stranger, might be able to make up his own mind about me without already having formed an opinion based on drivel that needed to be overcome or ignored,” he wrote in Journey Without a Map. That place turned out to be (after another stint in France, where reruns of Adventures in Paradise had made him a sensation) the Sahara desert, where he rode from the Red Sea to the Atlantic coast with the Egyptian camel corps.

Perhaps creatively galvanised by a prolonged spell in a vast void the size of the U.S., McKay returned to his country of birth and began living by the pen, writing plays including the well-received Sea Marks, and several novels. One of his last, the thriller Toyer, about a twisted playboy who inflicts psychological torture on his victims then sends them into a drug-induced coma, is no beach read, but it became a bestseller. Many of his shorter writings — of which he often did readings on public radio stations in Hawaii — won critical plaudits (his play Sea Marks won a writing gong from the Los Angeles Drama Critics’ Circle).

The lust for rarefied experiences never dimmed, despite crewing on yachts in the Caribbean and hiking through the jungles of the Amazon (he once made his own way, on foot, across Venezuela, and it was also in the rainforest that he completed that two-year gig as an agronomist). Even in the relatively settled period of his life, living in Beverly Hills, serving as drama critic and theatre editor for the Los Angeles Herald Examiner, and teaching play writing at U.C.L.A., his yen for the spicier life prevailed. (“Gardner had a passion for lions and cheetahs, and actually had pet cheetahs at his place in Beverly Hills until his neighbours complained,” his friend, the actor Colby Chester, recalled. “I remember going with him to visit one of his lions, which was being housed on a game farm in Tujunga. I remember him saying, ‘It’s probably best if you don’t go in the cage with me’. I didn’t know quite how to take that. I remember watching him literally lying down with his lions.”)

Some light into McKay’s extraordinary psyche is shone by a comment he made to People magazine in 1999. “I never knew what I was searching for,” he said, “only what I was not searching for. My life is defined by what I’ve quit.” While his life narrative offers us only glimpses of what made the man tick, it offers some edifying insights into a bygone era. Here in 2018 — especially if you’ve mistakenly flicked through the latest Freeview offerings in a bored after-dinner moment — the story of a dashing young man who spurned cheap fame for rich adventure and artistic accomplishment makes one feel not only vigorous admiration for that individual but for the values of an era that was culturally more edifying.

This article originally appeared in Issue 58 of The Rake.