Manhattan Love Story: Truman Capote & Jack Dunphy

The last in our series of rakish romances features another which broke all the rules, and blossomed all the more for it – Truman Capote and Jack Dunphy.

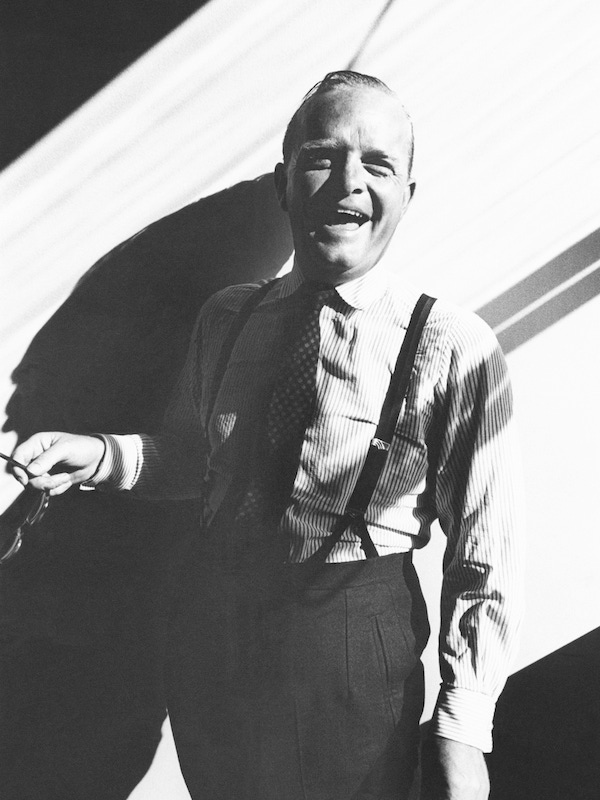

It wasn’t the most auspicious of romantic first encounters, the evening that a man born Truman Streckfus Persons from New Orleans met eyes, at a social soiree in the Manhattan home of a mutual acquaintance, with the Atlanta-born Jack Dunphy. It was 1948, and Truman had recently been made a celebrity overnight by the success of his first novel, Other Voices, Other Rooms.

Trained in ballet, Dunphy had just toured with the Balanchine company in South America before marrying a fellow dancer from Philadelphia, then treading the boards with his newly-wed in the original Broadway production of Oklahoma!. Truman was 11 years his junior. Within months, The Lavender Scare - the mass witch-hunt that saw gay people fired from the United States government – would deliver, on a platter, post-war America’s grizzly attitudes to homosexuality.

But it wasn’t the least auspicious first encounter, either. Dunphy was by now divorced, and had ditched the performing arts to become, like Truman, an author (his novel John Fury, exploring the lives of the impoverished Irish in Philadelphia, Dunphy's hometown, had been called “remarkable...warm and strong” by a prominent New York Times critic). The attraction to his future lover, for Dunphy was instantaneous – “Truman arrived wearing a little cap and showing off,” he later said. “I thought he was adorable.”

But what really underpinned the mysterious, one-size-fits-one compatibility between the two men who began a 35-year relationship that evening? The answer may lie on the pages of the further novels Dunphy would go on to write, which dealt lucidly and sensitively with human despair and loneliness. Truman, meanwhile, was an existential quagmire who would, one might speculate, have engaged Dunphy’s interest in the darker avenues of the human condition. A troubled but precociously brilliant but lonely child, by many accounts, who taught himself how to read and write, Truman had lived mostly in Alabama with cousins and aunts in his formative years (his parents lived in New York), causing a separation anxiety that he later said felt like being “a spiritual orphan, like a turtle on its back”.

Harper Lee, who became the girl-next-door turned childhood friend during this period, later based the character Dill in “To Kill a Mockingbird” on Capote, and one particular sentence - “We came to know him as a pocket Merlin, whose head teemed with eccentric plans, strange longings, and quaint fancies” – speaks volumes about Lee’s own perceptions of the complex man who would become her close companion, and even enlisting her as a researcher.

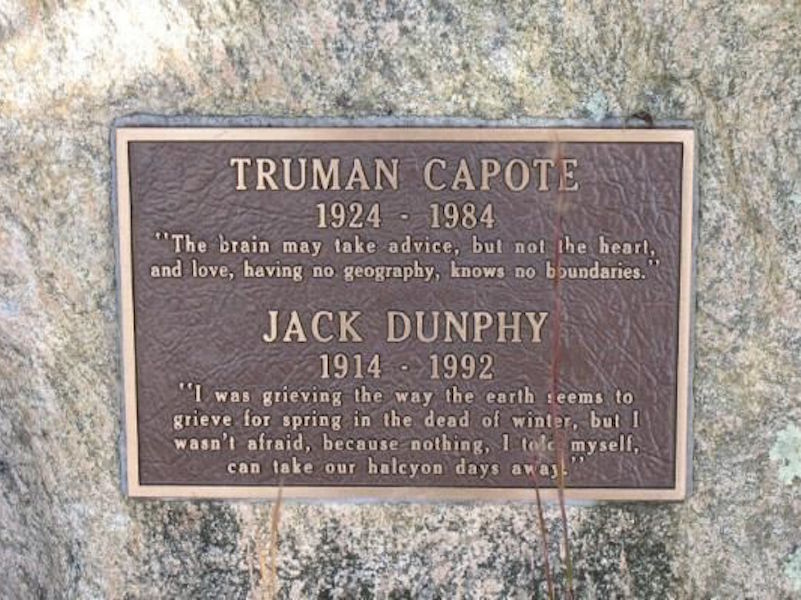

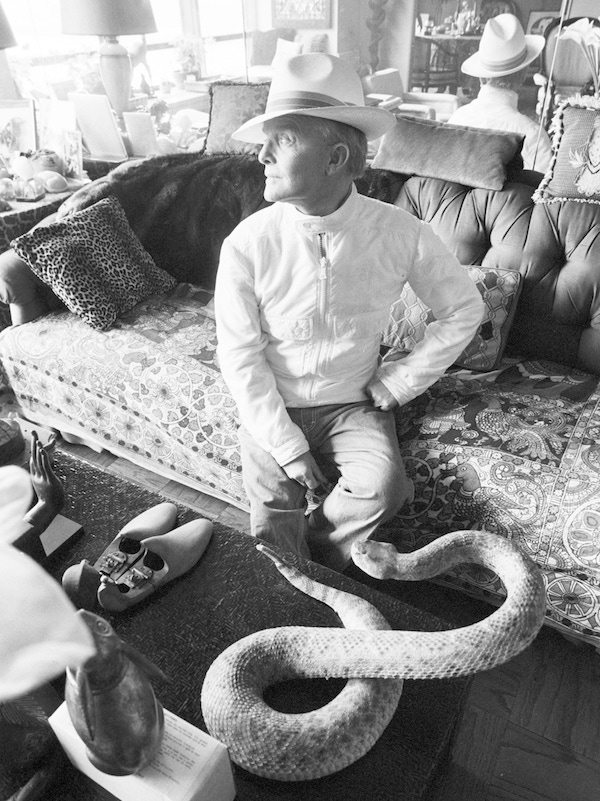

“Truman arrived wearing a little cap and showing off,” he later said. “I thought he was adorable.”Loneliness and an acute sense of displacement prompted in Truman the need to project a flamboyant personality, an endeavour usually underpinned by with copious alcohol. He had a mile-wide obsessive streak – his non-fiction novel In Cold Blood consumed more than six years of his life – and by the time he trashed his own lofty social existence (this is a man who, in 1966, held a masked ball at the New York’s Plaza Hotel for some 500 of his “very closest friends”, including his “swans” Slim Keith, Gloria Vanderbilt and Babe Paley) by skewering his famous friends in a excerpt of his unfinished novel published in Esquire, he’d begun a slide which ended, via alcoholic bloat, with his death from what the coroner described as "liver disease complicated by phlebitis and multiple drug intoxication”. His quirks, qualms and peculiarities - all resurrected with chilling persuasiveness, languid high-pitched voice and all, by Phillip Seymour Hoffman in the 2005 biopic – would, it’s fair to surmise, have seduced Dunphy. And Capote’s feelings for him? During their halcyon period as a couple – at their Manhattan apartment together, or during jaunts to the Swiss Alps or Portofino – they would often write together, and always read each other's manuscripts. After reading Dunphy's fifth novel, First Wine, a tearful Capote apparently asserted, simply: “Jack, you're a great artist.” Dunphy would always be overshadowed by his lover. Most of Truman’s short stories, reportage and novellas (Breakfast at Tiffany’s, The Muses Are Heard, The Grass Harp, Local Color, The Dogs Bark, Music for Chameleons) were vast commercial successes. But neither disparity in the height of the two men’s star, nor lengthy periods apart (“We were always… repeating the pattern that had commenced in childhood, when one's need to escape from one's own kind was so savage, so burning in its intensity, that had either of us stayed home, he would certainly have perished,” Dunphy later said) ever tarnished the relationship. A portion of Capote’s ashes would eventually be mixed in with Dunphy’s when they were scattered on Long Island, eight years after Capote’s death, in 1992: a fitting tribute, perhaps, to the fact that it’s not just absence, but turbulence, too, that makes the heart grow stronger.