Invitation Only: Truman Capote's Black and White Ball

Truman Capote's Black and White Ball was quite possibly the most extravagant party of the 20th century, only fitting then that The Rake should dissect it.

Even before a single cork had been fired, it was obvious that Truman Capote’s Black and White dance would be a party for the ages. A fever-dream collage of diplomats and dilettantes, movie stars and Maharajahs, the ball’s guest list was an Encyclopedia Britannica for name droppers, while its host was both the most celebrated writer of his era and an acknowledged social chessmaster with a carnival eye that made The Great Gatsby look like The Sort Of Just Okay Gatsby. A Last Days of Rome bacchanal for the American Golden Age, the greatest party in the history of the world took place 50 years ago this month. But for those who were passed over for an invitation, it probably still stings like it was yesterday.

“One man told Truman his wife had threatened to kill herself if she weren't invited”, remembers editor of The New York Review of Books Robert Shivers. Property baron and ‘man-about-everywhere’ Jerry Zipkin (who Capote famously described as having “a face like a bidet”) pretended to be called away to Monte Carlo when he realised he was in for a snub, while Upper East Side brahmin John Gallihan recalls how dozens of international jet-setters attempted to “bribe Truman with great sums of money” in order to get their name on the sacrosanct list. As Parisian aristocrat Étienne de Beaumont once put it: “A party is never given for someone. It is given against someone.”

And that was precisely how Capote liked it: all murmurings and histrionics and subplots and scrabbling in the margins. Things had been much the same in the months that led up to the release, in January 1966, of In Cold Blood, the novel that had catapulted him simultaneously into the literary world’s limelight and into the laps of a dwindling American high society (sometimes literally, in fact: at five foot two, Capote was often labelled the ‘lapdog’ of the great society hostesses; they in turn referred to him cooingly as ‘Tru Love’ and ‘Tru Heart’.) It also scraped him “right down to the marrow of my bones”. After half a decade in the Stockholm Syndrome clutches of a gruesome murder case, Capote knew that this would be his last book for some time. If the circus was to continue, then the carousel would have to keep spinning of its own accord. The Black and White dance was its jet fuel.

Perched on the Hampton's poolside of one of his many collected heiresses, Capote set to the task of drawing up his plans with a fervour usually reserved for his novels (“The party was the product of a literary mind” notes Capote’s biographer Gerald Clarke). More a cast list than a guest list, the stack of thick-cut invitations saw a cornucopia of international players dance on Capote’s imagined stage: president’s daughters and disgraced European princes and international film stars; Croesus-rich oil barons and riviera playboys; literary titans and lily-white debutantes.”There was a slight note of insanity about that guest list” remembered Katharine Graham, the editor of the Washington Post who Capote, in a social masterstroke, dedicated the ball to. But for the author, the exercise held the cool rationale of a laboratory experiment: “I have thought for years that it would be interesting to bring these disparate people together and see what happens” he told Esquire magazine years later.

As the invitations began to cascade through 540 gilded letter boxes, the relief at making the cut was soon overtaken by another nausea entirely: the question of what to wear. Capote had specified a dress code of strictly black and white, and insisted that everyone wore a mask (“I haven't been to a masked ball since I was a child” he explained.) The rush to Manhattan’s dressmakers and milliners was apocalyptic. “The ladies have killed me” wheezed the deflated young hat maker at Bergdorf Goodman, while a bespoke mask maker eulogised over the “many birds that have donated their feathers to the cause.” Capote’s own mask cost him just 35 cents from toy shop FAO Schwartz.

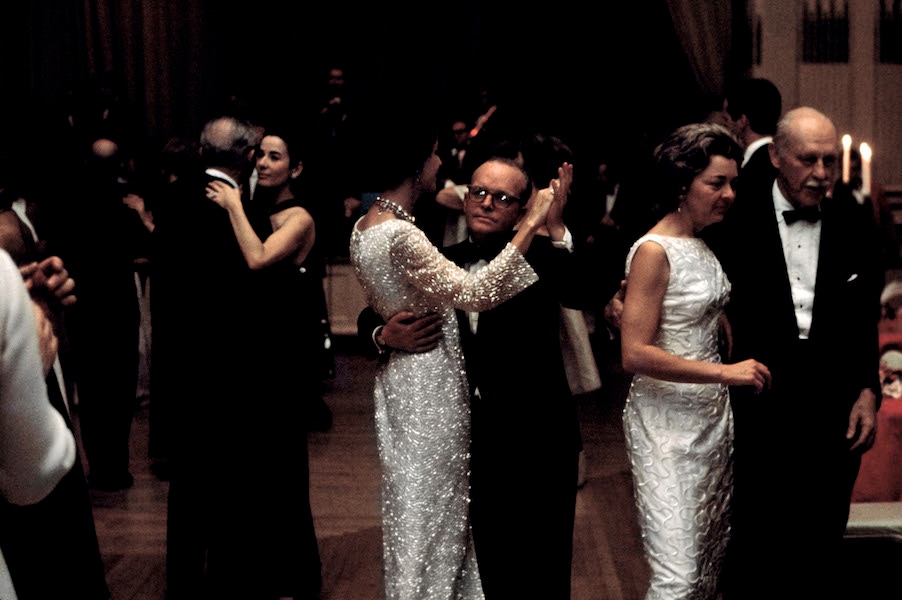

And then, at eight o’clock on the 28th of November, the floodgates – so long under siege – burst open. A throng of gawkers, hopeful reporters and autograph hunters swelled at the main entrance to the Grand Plaza hotel, held back only by a phalanx of police-sawhorses, put-upon junior officers and some well-disguised members of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s secret service. The torrent of guests poured into Capote’s receiving line two-by-two – like bedizened animals jaunting onto the Ark while a voice from the heavens announced their names to cheers and faints and whispers. Inside, 450 bottles of Taittinger popped in unison (flowing, according to actress C.Z Guest, “like the Nile”), before unlikely dance partners swirled and eddied across the marble floor to the swing of Peter Duchin’s big band (“Everybody, no matter how rich or sophisticated, was rubbernecking’ remembered Aileen Mehle”). An impromptu game of American football broke out with economist John Kenneth Galbraith’s silken top hat as the pigskin; Frank Sinatra beat his fists on the table and demanded twenty bottles of Wild Turkey bourbon; a satin-gloved fist fight broke out over the rumblings of the Vietnam War; masks were cast aside, marriage proposals extended, celebrities concocted; and Capote stood in the half light, at once a proud parent and a saucer-eyed child, in gentle awe at his creation.