MAD ABOUT THE BOY

Guy Madison was one of Hollywood’s original ‘beefcakes’, a man known and adored more for his looks than his acting talent. But in the burgeoning visual age of the mid 20th century, that was more than enough.

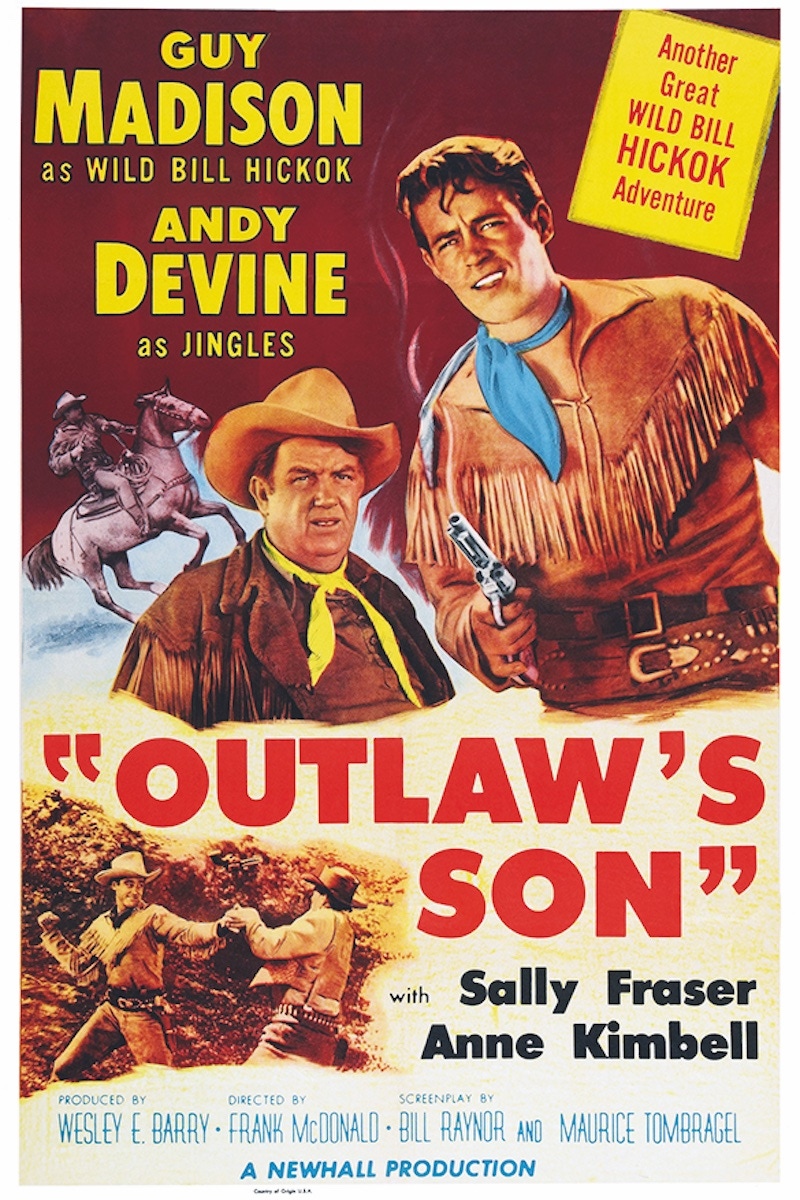

He looks like just another Hollywood hunk to us now, but Guy Madison was once one of the most familiar faces in America. His role as television’s Wild Bill Hickok in the 1950s made him one of the biggest stars on screen, an icon of undemanding mass entertainment. The tough-but-fair cowboy figure he established in that role was what would keep him in work for 40 years, but in truth that was already his second act. Before then, he had made his name as one of the first male pin-ups of a new era of film, packaged and sold to the public as a sex symbol, regardless of acting talent, in a manner that would help define the next 50 years of entertainment.

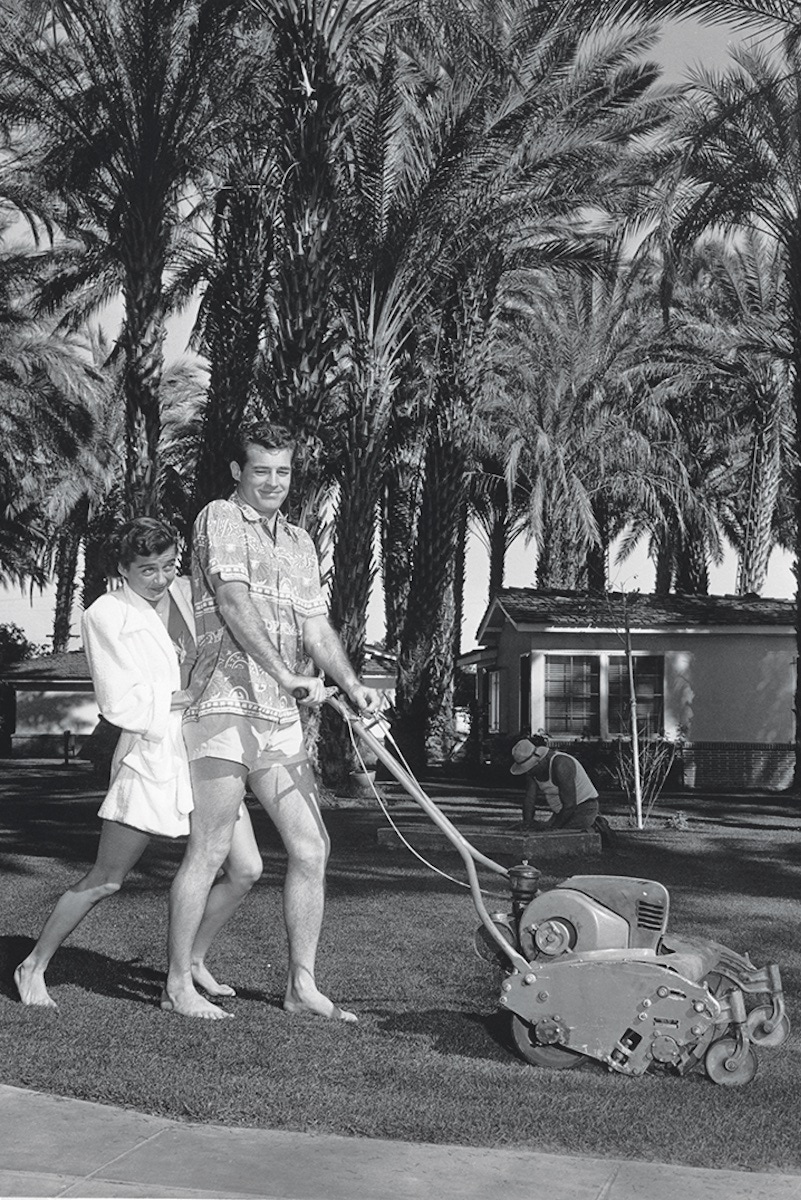

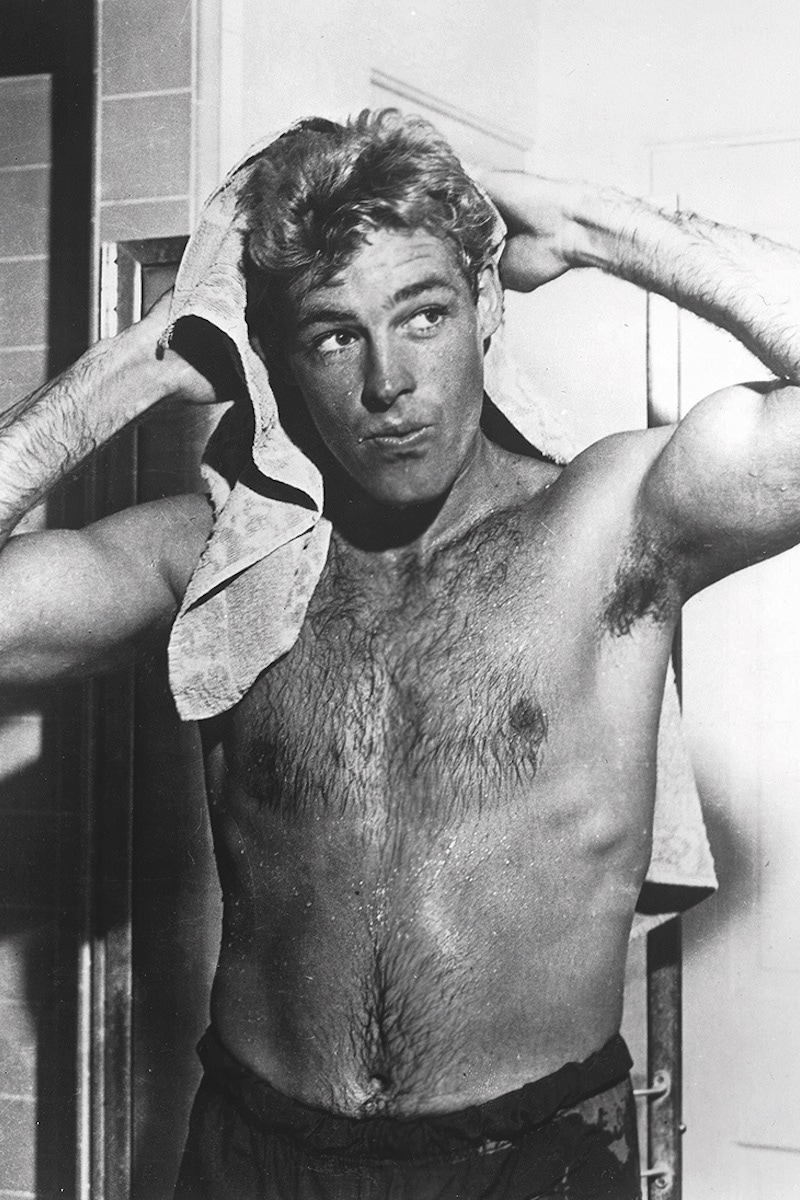

His first appearance on film, in 1944, is said to have caused girls to fall out of cinema balconies. The masculine square jaw, straight nose and, crucially, soft eyes made him just the right combination of familiar and unattainable. This picture of masculine perfection was zealously marketed via a steady stream of carefully sexualised photographs, usually taken at the beach and always without a shirt, putting him at the forefront of a new group of male stars quickly dubbed ‘beefcake’, to match the ‘cheesecake’ of the actresses who had long received the same treatment. As the Golden Age of Hollywood faded into an era of hastily made B movies and cheap television series, this was a way of grabbing attention in an ever busier marketplace, and one that worked. We may not remember Guy Madison often now, but for many years it took him into almost every American home and in many more around the world.

Beyond his head-turning looks, Madison was not suited for stardom, and even less ambitious for it. Born Robert Moseley, he was a shy boy, raised in the 1920s outside Bakersfield, an oil town that may have been in California but was spiritually distant enough from Los Angeles to have spawned its own strand of country music. His father was a railway mechanic and farmer, and Madison’s childhood was spent, usefully as it turned out, roping calves and breaking horses. He became not a cowboy but a telephone lineman, repairing broken wires, before he signed up for war service in the Coast Guard.

He was still serving when, on a weekend’s R&R, he attended a radio theatre broadcast and was spotted by a talent scout working for Henry Willson, on staff for David O. Selznick. The producer of Gone with the Wind and Rebecca, Selznick was persuaded to hire Moseley for a small part in his next feature, Since You Went Away, as a marine who appeared at a bowling alley with leads Robert Walker and Jennifer Jones. Overcoming his reluctance, Madison took it on as a diverting adventure and returned to his duties.

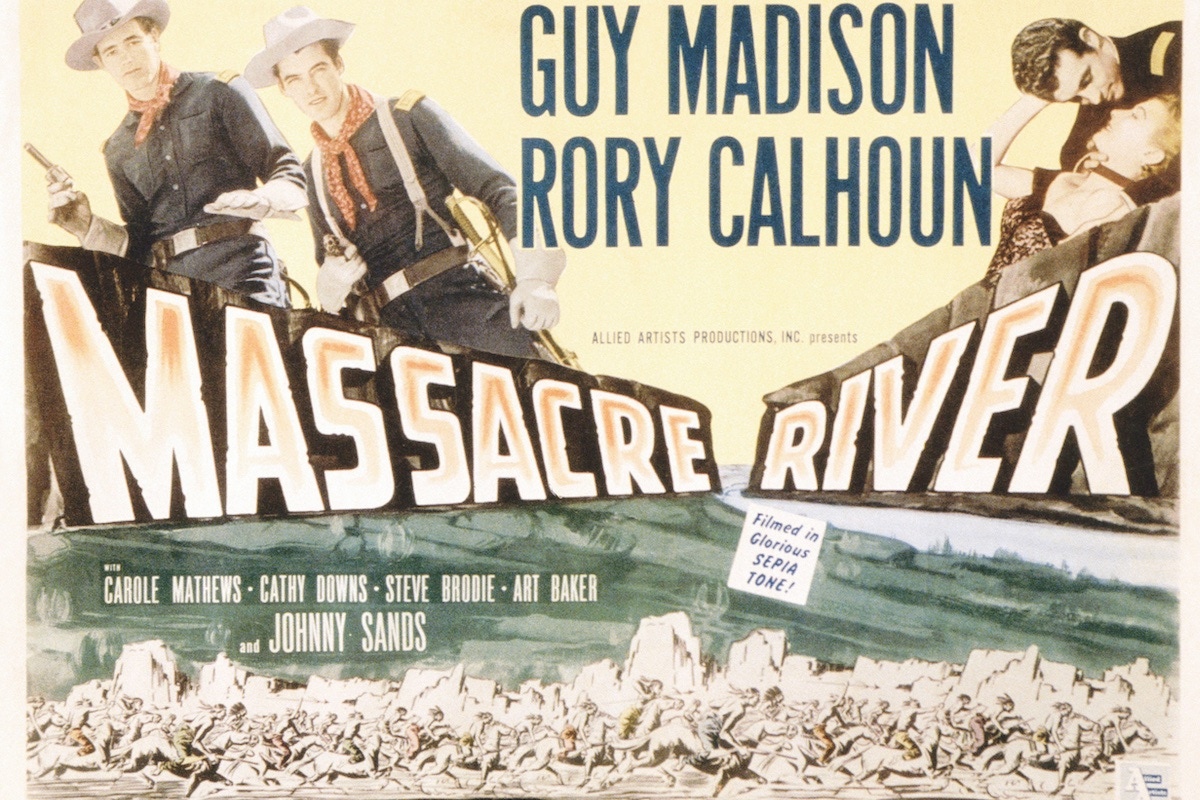

On the film’s release, the studio claimed to have received 43,000 letters, all asking for more information about this “dreamboat”. Willson made him his new project, one of many that would also include the equally handsome Rock Hudson and Tab Hunter, starting with a screen name. Moseley was nearly Rock, until it was felt that Guy better suited his boy-next-door qualities — the guy every gal wanted to meet. The rest was about being seen in the right places and accommodating the right people, very possibly including Willson himself. As with almost all handsome stars of Hollywood past and present, Madison’s sexuality is much debated. According to Darwin Porter’s Howard Hughes: Hell’s Angel, he was the lover of both Willson and Hughes, who supposedly clothed and housed him and flew him around the country on private jets. He may, too, have been more than friends with Willson stablemate Rory Calhoun.

Read the full article in Issue 76 of The Rake - on newsstands worldwide now.

Available to buy immediately now on TheRake.com as single issue, 12 month subscription or 24 month subscription.

Subscribers, please allow up to 3 weeks to receive your magazine.

Our customer service team can assist with any subscription enquiries at shop@therakemagazine.com.