Michelangelo and the yearning for tragedy

8 Minute Read

‘We lived in silence… He has only one way of expressing himself: his work.” So said Michelangelo Antonioni’s first wife, Letizia Balboni. It’s true, the Italian director was notorious for taking existential inquiry — and his own artistic purity — to another level. But what a legacy of film he left behind…

On a balmy evening in spring 1960, an audience of cinephiles at the Cannes film festival were getting hot under their dress collars. Boos, exaggerated yawns, loud jeers, and even derisive laughter attended the screening of Michelangelo Antonioni’s L’Avventura. Described by its director as “a type of film noir in reverse”, the picture told the story of a socialite on a boat trip with haute-bourgeois friends who vanishes on a remote island. Or, to be more exact, it didn’t. Not only was the central ‘mystery’ never resolved, the character simply evaporated from proceedings while her erstwhile boyfriend and best friend embarked on their own listless love affair. For the restive audience, this wasn’t so much delayed gratification as indefinitely postponed gratification. However, later that night, Roberto Rossellini and a group of influential filmmakers and critics drafted a statement announcing that they were “appalled” by the hostility, and expressing their admiration for Antonioni. Thus were two traditions born: the noisome Cannes cause célèbre and a certain kind of ruminative, opaque, usually European movie that felt to some like art-house homework and to others visionary modernism — but that provoked long nights of smoky argument in raffish cafes either way.

With his next two films, La Notte (a chilly portrait of an entropic relationship) and L’Eclisse (an emotionally exhausted couple never quite manage to connect), Antonioni came to exemplify this disdain for the niceties of plot, pacing and clarity. The novelist and screenwriter Alain Robbe-Grillet may have put it best: “In a Hitchcock film,” he said, “the meaning of what you see on the screen is constantly delayed, but at the end of the film you understand everything. With Antonioni’s films, it’s the exact opposite.” Antonioni was the emperor of existential ambivalence, the pope of ennui.

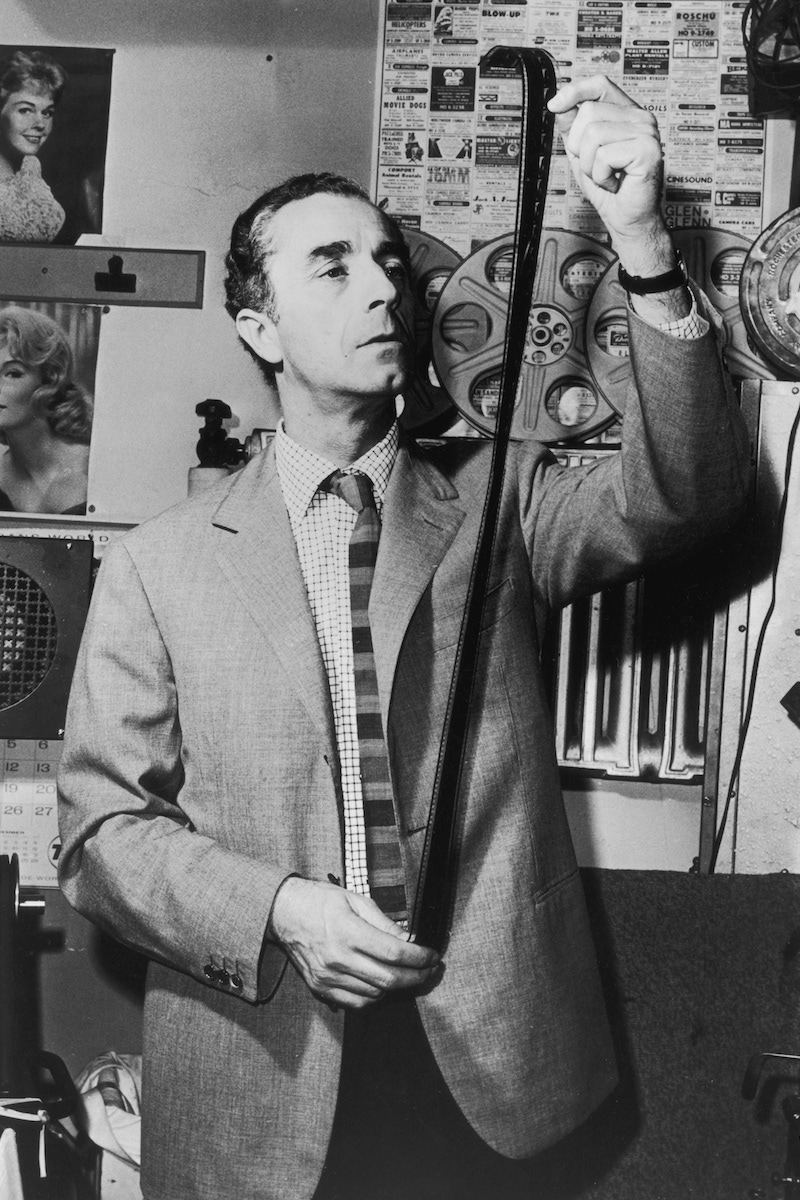

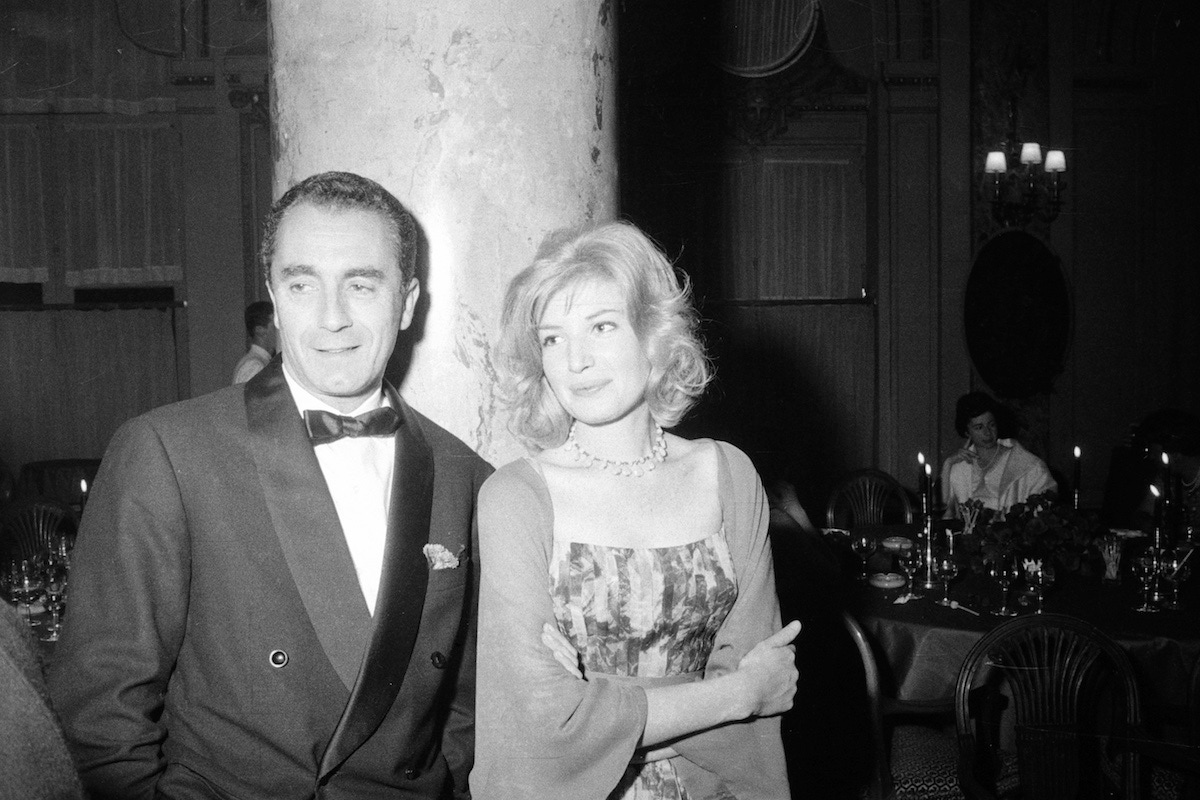

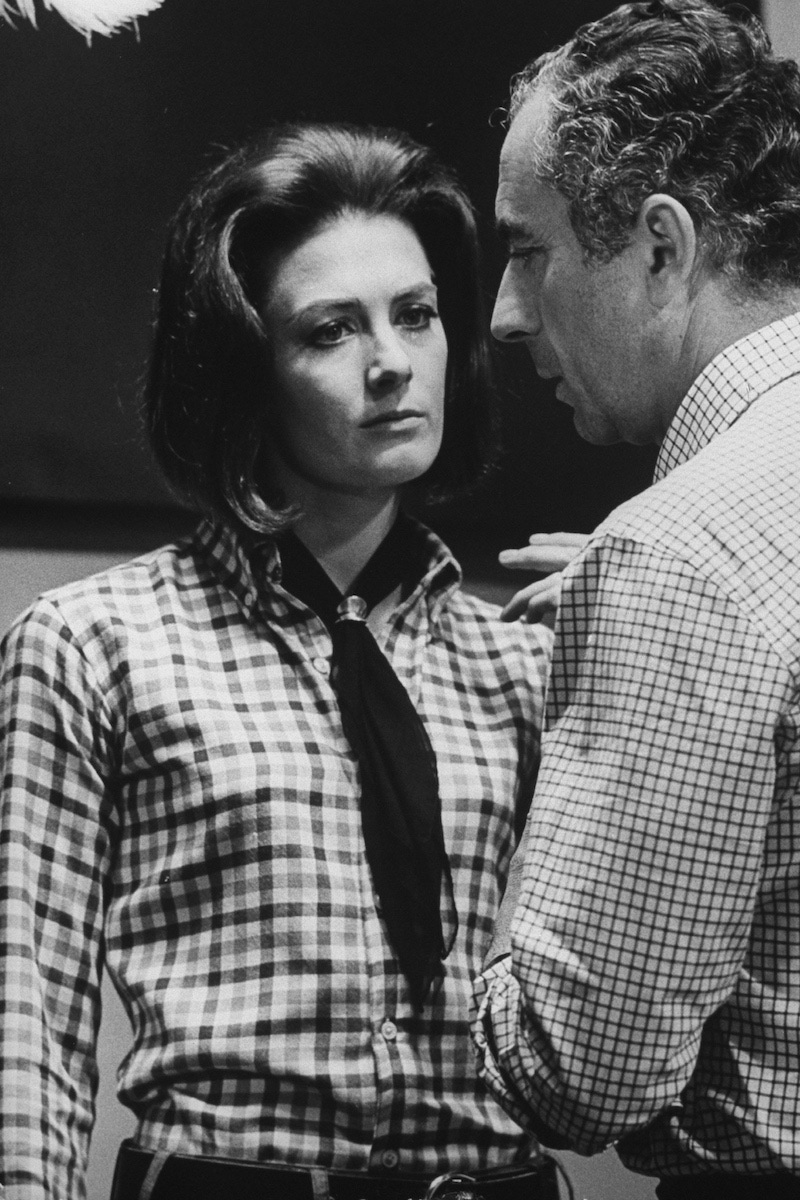

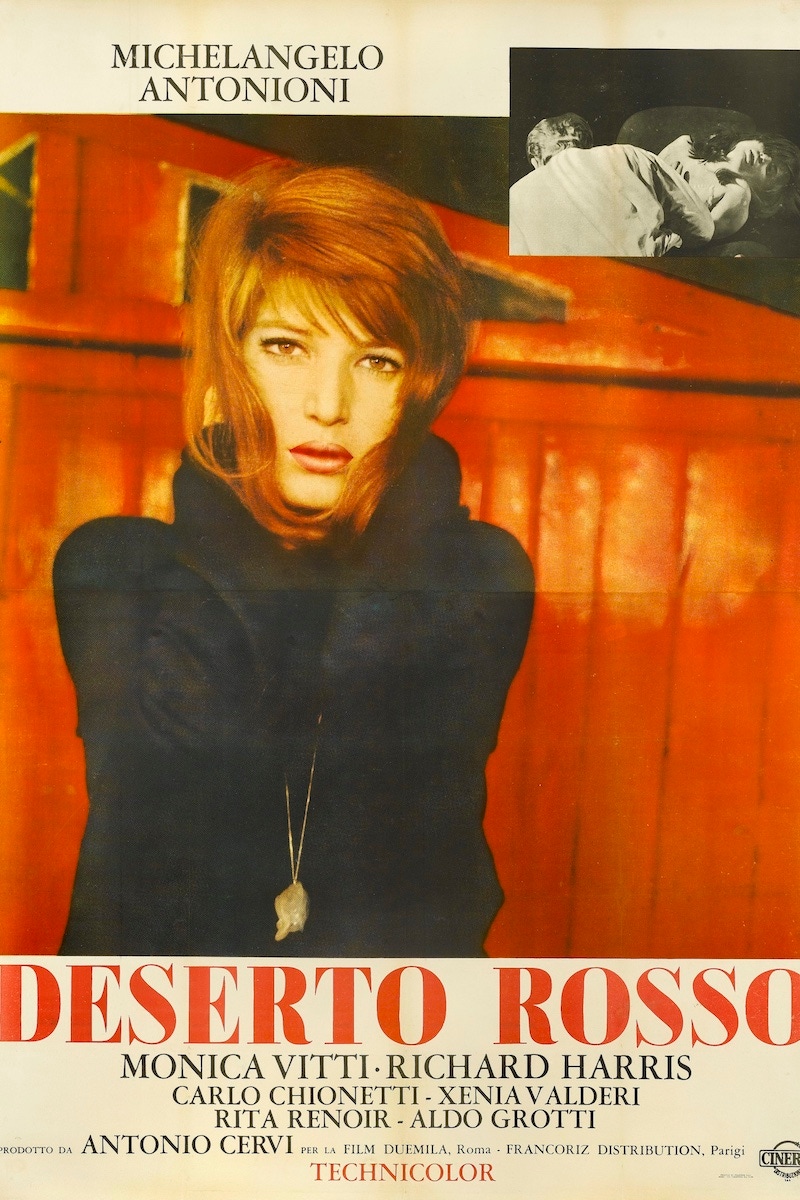

But what gorgeous ennui! All three films starred the luminous Monica Vitti (“an Italian Garbo,” reckoned Italy’s not-entirely-non-partisan press), whose angular cheekbones, intense stare, stark white shirts and belted trenchcoats remained in focus even as her character’s motivations slipped definitively out of view; her co-stars, including Marcello Mastroianni (in La Notte) and Alain Delon (in L’Eclisse), wore a sharp besuited and bequiffed proto-mod look that chimed with Antonioni’s highly formalised framing shots. “No Italian film director more than Antonioni has had such a knowledge of, and sensibility for, fashion,” says Eugenia Paulicelli, the author of Italian Style: Fashion & Film From the Early Cinema to the Digital Age. He also had an architect’s eye for the language of planes, angles and heights, and invested concrete objects and desolate cityscapes with a kind of latent emotive power. Would-be interviewers, meanwhile, found Antonioni himself to be as concertedly abstruse as his films. With his high forehead, beetle brows and mournful eyes, he resembled an irredeemably gloomy cardinal. “Even when he is telling stories about himself, Antonioni’s face remains set in its habitually serious expression,” Melton S. Davis wrote in a 1964 profile for The New York Times Magazine. “Precise in manner, conservative in dress and quiet in speech, he could be taken for a banker or art dealer recounting an unfortunate business deal.” Statements such as, “I believe the tragic sentiment dominates all of contemporary life” further ensured that he would never be mistaken for one of the Chuckle Brothers.

Antonioni had been born in 1912 into a well-to-do family of landowners in Ferrara, northern Italy, “a marvellous little city on the Paduan plain”, he said approvingly, “antique and silent”. He began to design puppets and build model sets for them when he was 10; he was a founder of the University of Bologna’s theatrical troupe while studying for his economics and commerce degree there in the mid thirties, as well as, less predictably, one of its leading tennis champions. He wrote scathing reviews of American and Italian genre films for the local paper, and did a stint of military service during world war two, but his own first effort at directing — a documentary about the local insane asylum — went awry when the activation of his floodlights caused the unfortunate inmates to go into convulsions. This mishap may or may not have turned him against the neo-realist movement in post-war Italian cinema championed by Rossellini and others; at any rate, he endured some penury — he recalled once being driven to steal a steak from a butcher’s shop — before, at 38, he found backing for his first feature, Cronaca di un Amore (Story of a Love Affair), which set the diffuse, alienated template for his future oeuvre. Another inside-out noir, the ostensible plot — a man and woman conspire to kill her husband — is abandoned after the latter’s unexplained disappearance (did they actually do him in? Was it suicide? An accident? We’re none the wiser) in favour of the couple’s enervated anomie. Here were the flourishes that cineastes would come to recognise as Antonioni-esque: stark settings; fussily composed scenes; shots that were held a few beats longer than necessary; dislocation; unease. When, in 1954, his 12-year marriage to the actress Letizia Balboni fell apart, she revealed that the gap between art and life was, for Antonioni, fittingly opaque: “We lived in silence. We reached the point where we communicated with each other only through the characters he created. He has only one way of expressing himself: his work. What he does is have his actors live out emotional crises in his films, by proxy living out the crises in his own life.”

If Antonioni’s formal daring reached its height during his imperial phase, so too did his elliptical imprimatur. The much-discussed ending of L’Eclisse features a montage of 58 unpeopled shots on and around a street corner where Vitti and Delon’s characters habitually met, including water seeping from a barrel, the screech of a bus’s brakes, and the roar of a passing airplane: Antonioni said it was intended to show “the eclipse of all feelings”. Following the film’s U.S. premiere, the director took the opportunity to visit the abstract expressionist Mark Rothko. “Afterwards,” recalled Antonioni’s second wife, the model Enrica Fico, “he wrote Rothko a letter in which he said, ‘You and I have the same occupation. You paint, and I film, nothingness.’”

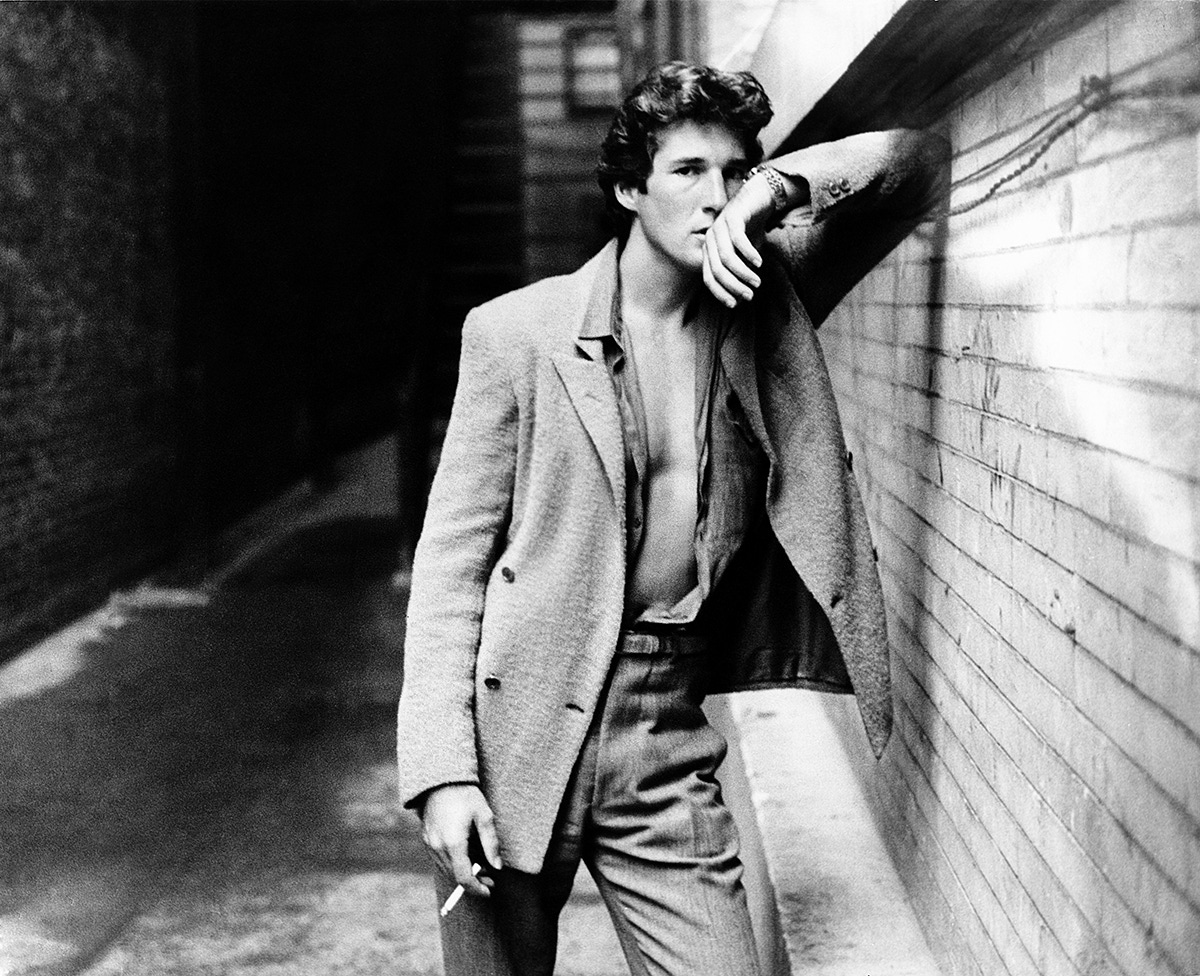

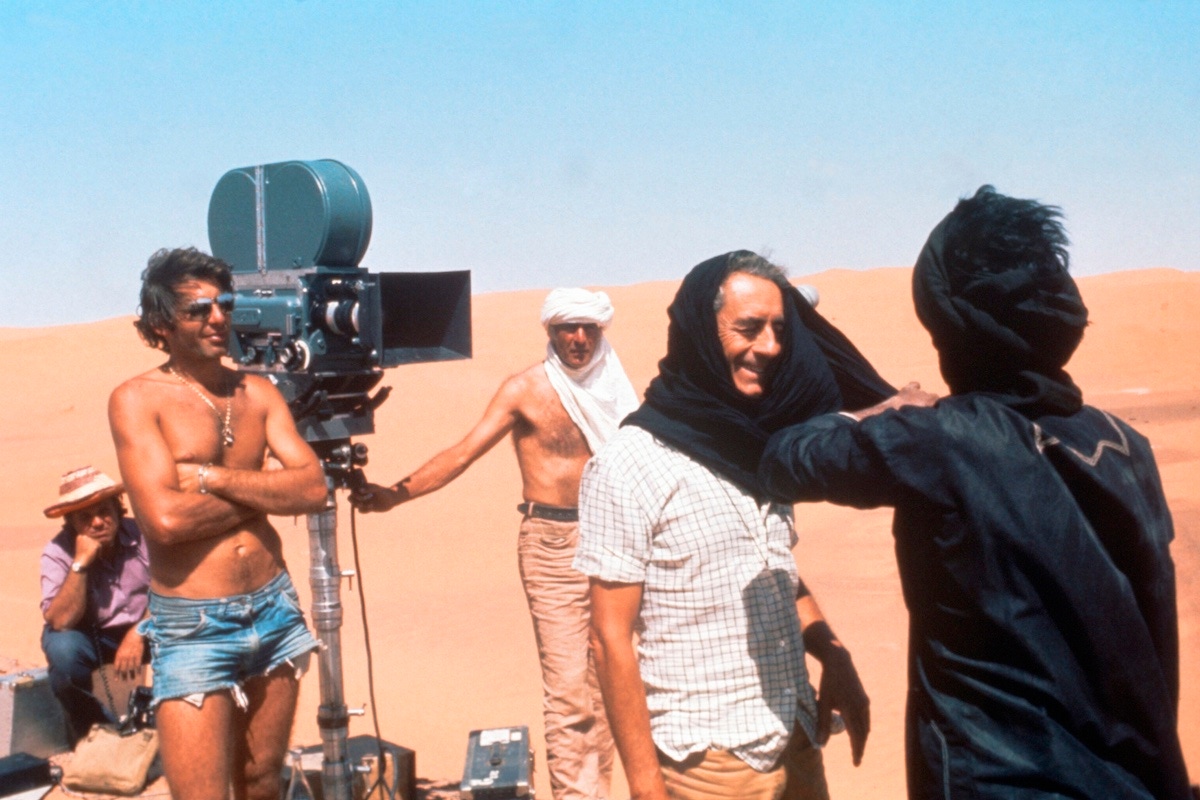

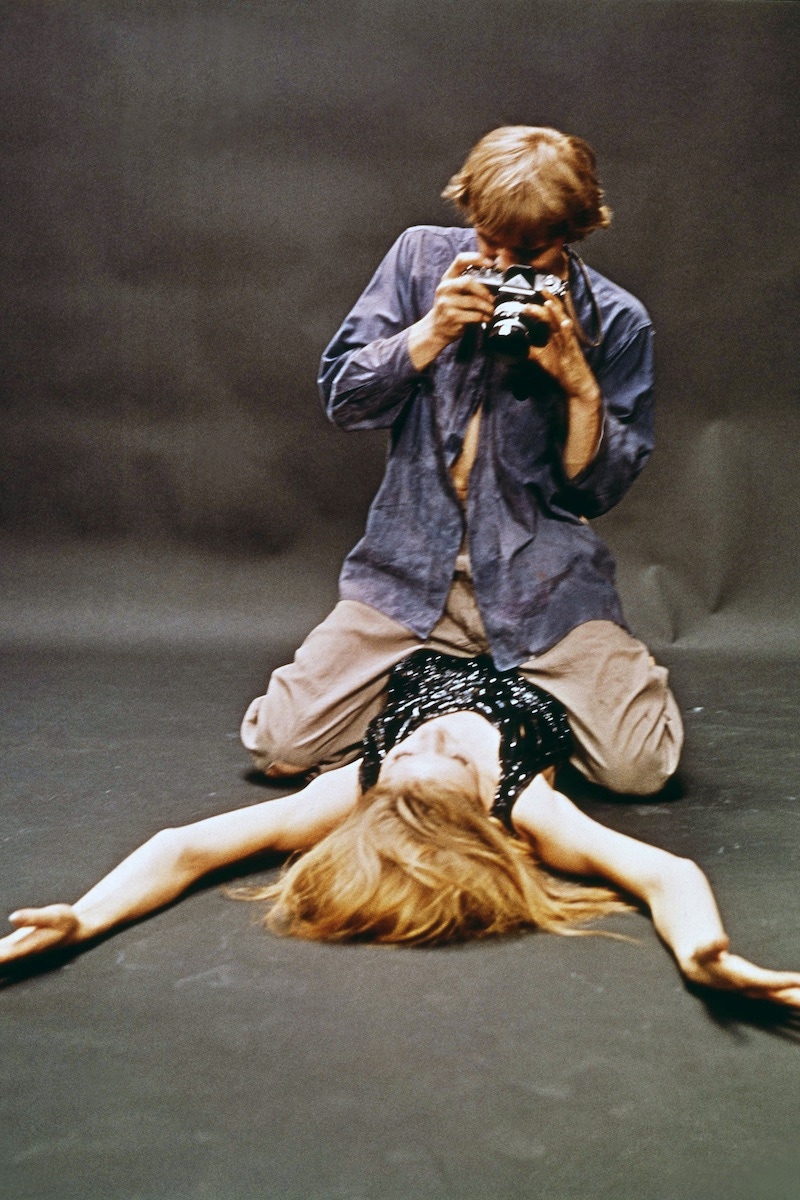

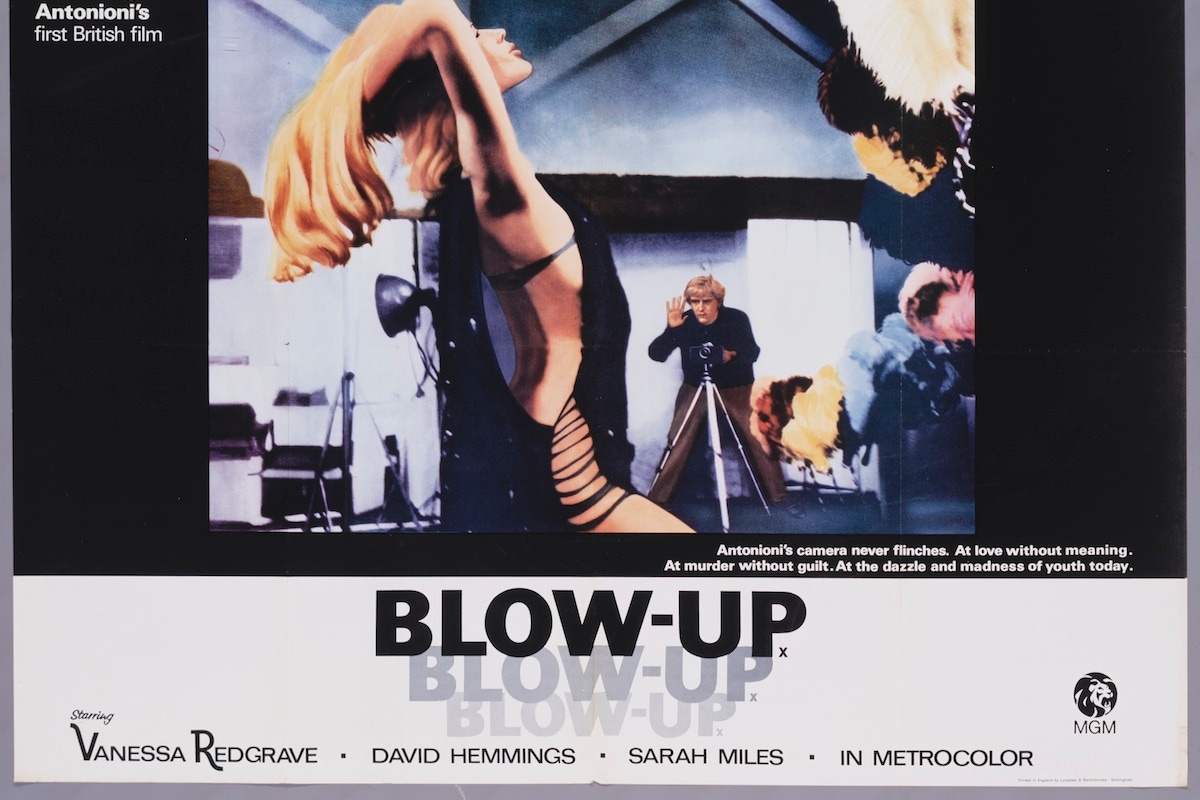

All of which suggests that MGM would have had some inkling of what they were getting into when they signed Antonioni to a three-picture deal in the mid sixties. The first fruit of that deal, 1966’s Blow-Up, is often cited as a cultural lodestone for London’s Swinging Sixties (by cheerleaders and detractors alike) due to David Hemmings’ portrayal of a Bailey-esque fashion photographer zapping from studio shoot to impromptu orgy in a soft-top Rolls-Royce. But the film’s air of heightened, if not deranged, reality — Antonioni ordered whole areas of Woolwich to be spruced up for the shoot, with grass painted a greener green and pigeons dyed to look more pigeon-y, and the film’s central murder mystery is inevitably jettisoned in favour of a concluding game of imaginary tennis with a group of drugged students in alarming clown make-up — means it takes place in no other realm but Antonioni-land. Similarly, his ‘American’ movie, 1970’s Zabriskie Point, ostensibly deals in student radicals fighting the despoliation of the Death Valley desert by developers, but the Easy Rider/Bonnie & Clyde ambience loses out to a 15-minute closing sequence of slo-mo explosions of modernist homes and their consumer durables (including, at one point, what looks suspiciously like an airborne frozen chicken) set to a Pink Floyd wig-out that is the equal of the cosmic light show that caps 2001: A Space Odyssey (it’s no surprise that Stanley Kubrick, another chilly, exacting auteur who seemed to prefer camera movements to people, was a big fan of Antonioni in general and Zabriskie Point in particular). Finally, 1975’s The Passenger, perhaps the director’s most approachable film, finds Jack Nicholson (never better) as a godforsaken journalist who attempts to escape his life by assuming the identity of a corpse he stumbles across in a hotel bedroom; unfortunately for him, the body is that of a gun-runner. The film concludes with a 10-minute bravura tracking shot that — in possibly a first for Antonioni — unites all the characters and narrative threads, though this wasn’t enough to save it, or Zabriskie Point, from flaming out at the box office. They would benefit from subsequent critical reappraisal, though too late for Antonioni, who declared at the time: “Hollywood is like being nowhere and talking to nobody about nothing.” (Which, it has to be said, sounds like the Platonic ideal of an Antonioni film).

No matter. By this time, Hollywood’s less mainstream denizens, along with the wider creative community, had begun to take notice. Antonioni’s slippery influence can be felt in the work of directors as diverse as Wim Wenders, Andrei Tarkovsky, David Lynch, Bruno Dumont, and Nuri Bilge Ceylan; in Nouveau Roman authors such as Robbe-Grillet and Nathalie Sarraute; and even in music (what is Björk’s line, “There’s definitely definitely definitely no logic/To human behaviour” if not a precis of the Antonioni oeuvre?). Antonioni directed only intermittently through the 1980s and 1990s, before dying in 2007 aged 94, but his reputation had grown in the interim: he was presented with a Lifetime Achievement Oscar in 1995, and his champions included David Thomson, the author of The Biographical Dictionary of Film, who wrote: “I suspect that Antonioni’s best films will continue to grow and shift, like dunes in the centuries of desert.” And like many of those films, Antonioni remained gratifyingly recondite to the end. “In a world without film, what would you have made?” one interviewer asked him. One can imagine him arching his brows with Olympian hauteur before delivering his sonorous reply.

“Film,” he said.

This article originally appeared in Issue 68 of The Rake.