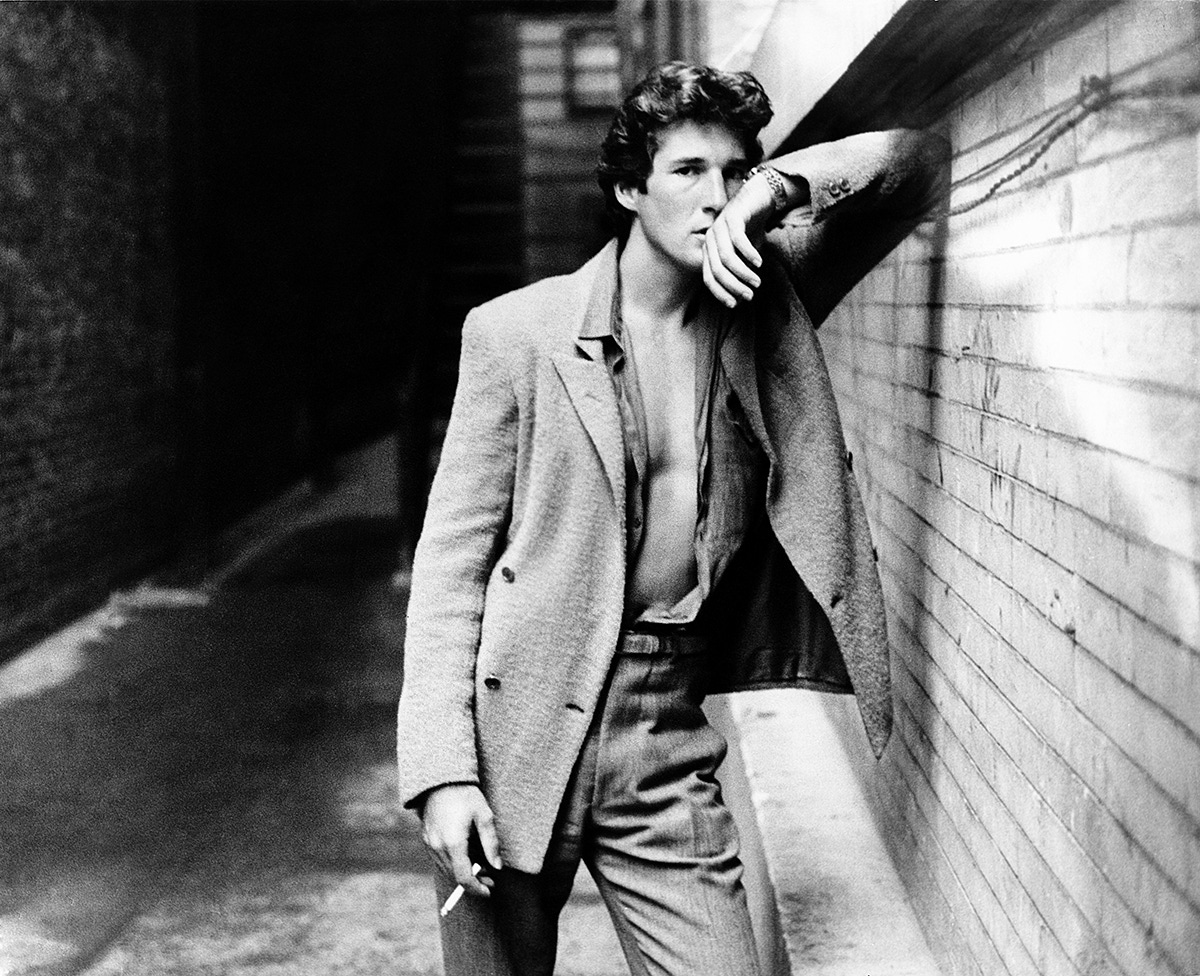

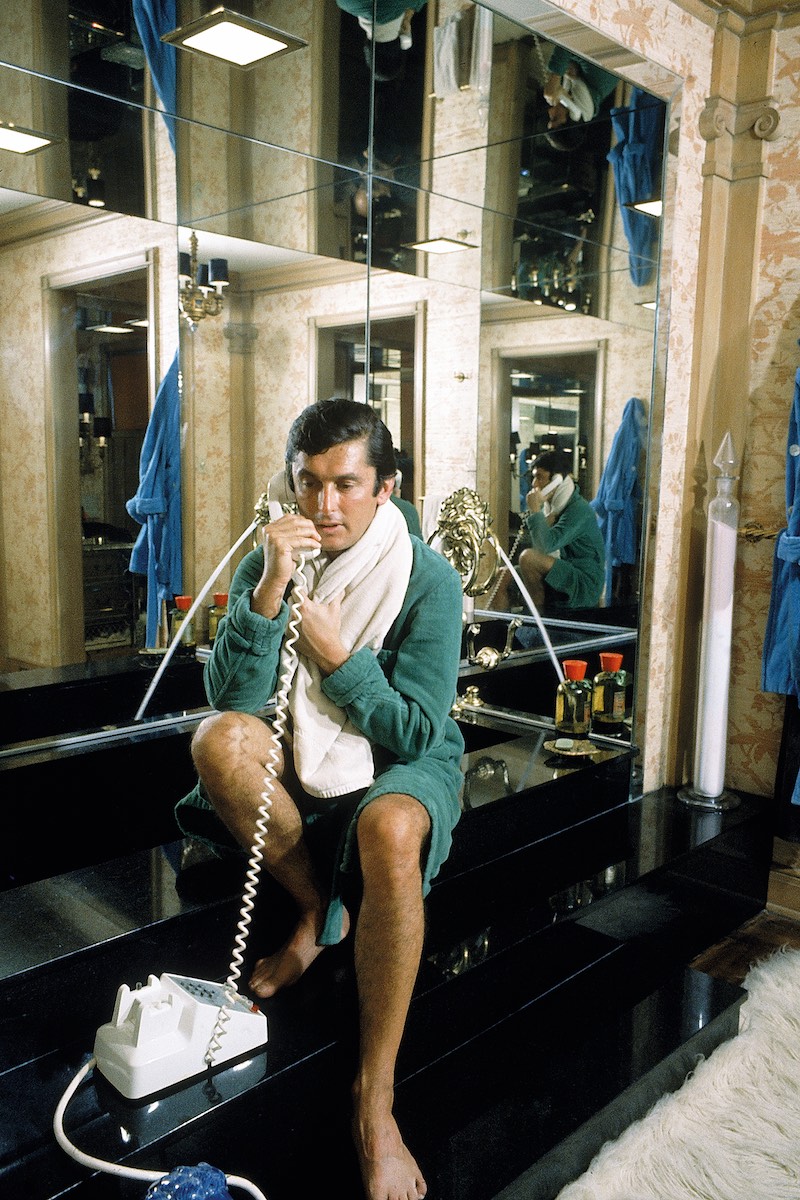

ROBERT EVANS: THE LAST TYCOON

Robert Evans was the film producer turned myth maker who brought classics such as The Godfather, Rosemary’s Baby and Chinatown to the screen. By the end of a life that was both glorious and turbulent, he’d ensured Hollywood would never be the same again.

Scott Fitzgerald once wrote that “there are no second acts in American lives”; the film producer Robert Evans would beg to differ. The life of Evans, who died in October 2019 aged 89, had a pristine Hollywood three-act structure, full of twists and tragic flaws. As head of Paramount, he produced some of the most admired American films ever, married seven times, and was a hypnotic raconteur with a unique sense of style. But he was also ostracised from the film business for a catalogue of terrible decisions. Evans had elements of both Fitzgerald and Gatsby: addictive, charming, contradictory, prodigious and tantalisingly unfulfilled.

Born in Manhattan in 1930 to Jewish parents on the Upper West Side — his father was a dentist in Harlem — the young Evans dabbled in radio acting and fashion, creating a women’s clothing company with his brother, Charles. In 1956, Norma Shearer spotted him in a pool at the Beverly Hills Hotel and was so impressed she insisted he play the role of her husband, MGM head Irving Thalberg, in the film Man of a Thousand Faces. A headline at the time read, “N.Y. Businessman Dives In Pool and Comes Out a Movie Star”. Darryl F. Zanuck soon cast him as the matador Pedro Romero in the 1957 adaptation of Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises, against the wishes of Ava Gardner and Hemingway. Zanuck stuck to his guns, with the edict: “The kid stays in the picture.”

Having played one studio titan and won the loyalty of another, Evans bought the rights to a book called The Detective and produced its film adaptation, starring Frank Sinatra, Robert Duvall and Jacqueline Bisset. A glowing New York Times profile of Evans caught the eye of Gulf and Western head Charles Bluhdorn, who hired Evans to resuscitate Paramount, then the ninth-largest studio in Hollywood.

Despite minimal experience and industry sneers that he was no more than a handsome failed actor, Evans transformed Paramount into the most successful studio in Hollywood by repeatedly finding the sweet spot between artistry and profitability. His C.V. in the late sixties and early seventies is peerless: Rosemary’s Baby, Chinatown, Harold and Maude, Serpico, The Conversation… Even the more style-over-substance films, like The Italian Job or Robert Redford’s The Great Gatsby, had a tailored swagger. But his most monumental achievement was The Godfather and its sequel.

After a production riven with artistic differences over casting and the choice of director, Evans claims he rescued The Godfather in the cutting room from a “long bad trailer for a really good film” by ordering Coppola to add nearly an hour to it. His two guests at the premiere were his wife, the Love Story actress Ali MacGraw, and Henry Kissinger, his lifelong friend and tennis partner. The film won three Oscars, launched the career of Al Pacino (among others), and transformed the ambition of mainstream American cinema forever.

The company Evans kept mixed glitter with grit, from Jack Nicholson and Warren Beatty to the reputed Chicago mob fixer Sidney Korshak. Evans was supposed to be at Roman Polanski’s house the night Sharon Tate was murdered, but was providentially delayed at work. Evans was an inveterate gambler and, for someone gifted with so much good luck early in life, the winds of fortune reversed in the 1980s. He left Paramount to go independent and, after a couple of early hits (like Marathon Man), he lost his Midas touch with a run of commercial and critical duds.

The nadir was Francis Ford Coppola’s The Cotton Club, whose failure at the box office and mauling by the critics would be the least of Evans’s worries. A theatre producer called Roy Radin, an investor on the film, was killed in mysterious circumstances during the shoot, and Evans became a material witness. Evans was never charged (one of his ex-girlfriends was convicted with three of her associates), but it was not a good look.

Read the full story in Issue 70 of The Rake - on newsstands now.

Subscribe and buy single issues here.