Bulgari watchmaking: 'This was the turning point... We had to clean up'

In an excerpt from the new book 'Bulgari: Beyond Time', published by Assouline, Gianni Bulgari, scion of the family jewellers, tells ROBIN SWITHINBANK how a bold move into fine watchmaking helped the brand become the luxury behemoth it is today.

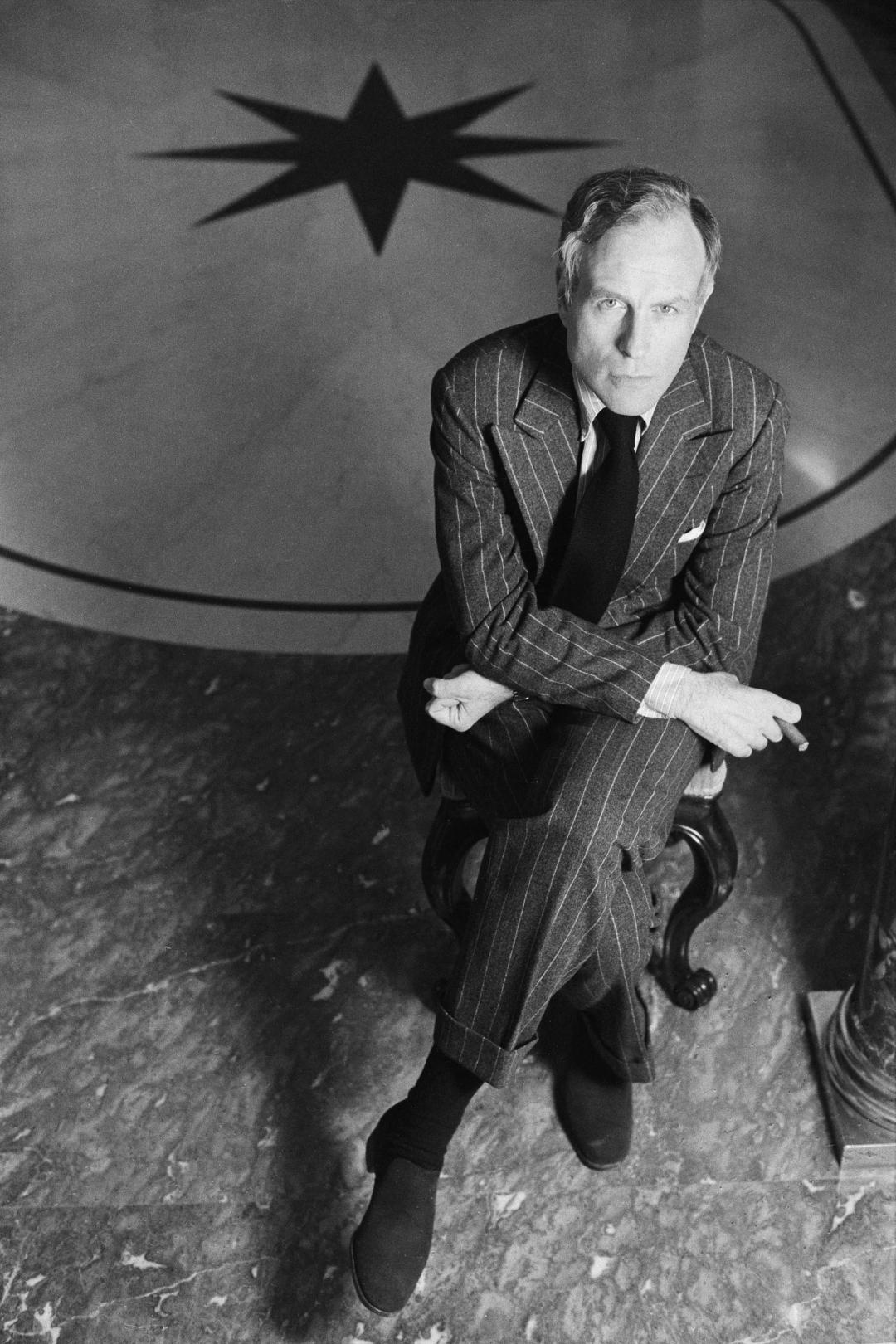

Gianni Bulgari has lived an extraordinary life. Scion of the Bulgari family, businessman, international socialite, confidant of Elizabeth Taylor and Gina Lollobrigida, kidnap survivor, pilot, racing driver, industrial designer, collector — and the creator of Bulgari Time. Mr. Gianni, the eldest grandson of Bulgari’s Greek founder, Sotirios Voulgaris (he Italianised his name to Sotirio Bulgari), does not give many interviews.

It’s an unseasonably warm January day when we meet in Rome. Mr. Gianni has invited me into his vast apartment in the hills above the Eternal City, and we’re sitting in a sort of receiving area, which feels more like the wing of a museum or gallery than a conventional sitting room. Among the columns and floor-to- ceiling windows is an eclectic mix of books, paintings, sculptures, marbles, bronzes, ceramics, vases and other ephemera, in an array of colours too numerous to count. I note we’re reclining in a pair of walnut-backed Art Deco armchairs that I recognise from a portrait taken of him perhaps 30 years ago. It’s a cornucopia of beautifully curated objects, all now fragranced with the faintly intoxicating scent of mid-to-late-20th-century Italian grandeur.

It was his decision in the 1970s to take the Roman jeweller into watchmaking. His decision to propel his family business into a space where it had no authority. His decision that precipitated one of the great watchmaking success stories of the past half-century, perhaps ever. It is this I’m hoping we can discuss.

He tells me that prior to the 1970s, when he took over the running of the company, the only watches with the Bulgari name on the dial had been co-signed as part of deals his father, Giorgio, had done with specialist fine watchmakers, such as Audemars Piguet and Vacheron Constantin. But this was long before he’d been involved in the business himself. Mr. Gianni says his own first encounter with the watch industry came in the 1960s, when he met a representative from Piaget and agreed to sell the Swiss maker’s watches in Bulgari’s Via Condotti store. “Piaget wasn’t a very well-known brand at the time,” he says. “But we made an exhibition of its watches, only with the disapproval of my uncle, who thought watches were a depreciation of the image of Bulgari.”

By this time, his father and Uncle Costantino had grown old, and Bulgari had, in Mr. Gianni’s words, an “old-school mentality”. His uncle disapproved of advertising, too, thinking it “horrifying”. Sotirio had been a talented silversmith and had opened his ‘old curiosity shop’ on Via Condotti in 1905. His influence over the company had reached well beyond his death in 1932.

To the second generation, Bulgari should remain a secret of sorts, known only to high society, to whom it would offer high- end jewellery, rare precious stones and antiques. “If you went to Bulgari, the first thing you would see was a fantastic collection of jade, silver and snuff boxes,” Mr. Gianni remembers. “Jewellery became more important because of the value of sales. We used to sell big stones, but never inexpensive jewellery.”

Giorgio would die in 1966; Costantino, in 1973. As Giorgio’s eldest son, Mr. Gianni took the reins, becoming the company’s chairman and chief executive. In the early years of his leadership, the company would expand internationally, opening stores in Paris, New York, Monte Carlo and Geneva. But if he was to fulfil his vision and transform Bulgari from traditional Roman jeweller into an international luxury brand, Mr. Gianni felt he would have to expand his product range — and make some of it, as he has it, “more accessible”. Mr. Gianni was well-travelled and knew the world. He spoke fluent French and English and had witnessed firsthand the impact of a period of global economic downturn. The decade’s wild currency fluctuations and rocketing gold prices had stifled growth, discouraging a new generation of potential customers from investing in luxury, a natural concern to the dynamic and increasingly influential young Italian businessman. At the same time, this was the dawn of the digital age, and electronics were already on their rapid march into every corner of modern life. Where notions of computerisation and digitisation had once been confined to the scientific community, they were now becoming modish.

Added to that, in 1975, Mr. Gianni had been kidnapped, spending 30 days in captivity until his family paid a $2m ransom to secure his freedom. The experience, he says, was boring, but where it might have ruined some (as was the case with John Paul Getty III), it re-energised him. “It improved me,” he says. “I had this idea before, but after it I said we have to position Bulgari in a completely different way.”

In 1977, he would close the business for a month to “clean the shop”, taking stock of inventory, managing the company’s muddled financial affairs and putting it on a firm footing from which it could launch into what looked like a promising future. “ThiswastheturningpointforBulgari,”hesays.“Itwasfundamental. We had to clean up.” With this as a backdrop, Mr. Gianni and Bulgari took their first tentative steps into watches. The Bulgari Roma was a small, round watch with a gold case that measured 30mm in diameter. It was set on a simple cord strap made of hemp and leather, to capture the casual trend for macram, and had a greenish liquid crystal display, or LCD, with a digital readout, lending it a touch of enlightened electronic cool. The words ‘BVLGARI’ and ‘ROMA’ were engraved on the case’s flat front, taking the bold step of integrating the company name into the watch’s design.

But it was not for sale. One hundred pieces were made and gifted to Bulgari’s best customers. News of the watch travelled, perhaps further and faster than Mr. Gianni had anticipated. Customers who had not qualified for the Roma began requesting a watch of their own. Few things breed desire quite like the feeling of being overlooked.

The following year, Mr. Gianni, now also the company’s creative head, introduced an analogue version of his Roma watch. It too was gold and only 30mm in diameter, but it had a black dial, with tall Arabic numerals at 12 and six accompanied by ultra- thin hour markers. Unbeknown to him, this aesthetic would become a Bulgari signature.

Lugs that flared out ever so gently from the case held a black leather strap in place, while inside was a mechanical movement powering needle-like hour and minute hands. As before, the bezel was engraved with the names of both brand and watch. If the watch seems small by contemporary standards of masculine watch design, there was little concern in 1976. “There was not such a difference in watches for men and women at that time,” Mr. Gianni says. “The biggest revolution in watches started in the 1970s and 1980s. Women started to wear watches that were originally for men.”

More significant to Mr. Gianni was where the watch might take his company. “Since the early 1970s, I’d been having doubts about this business,” he says, referring to the precious-stones trade he’d learned from his father. “I didn’t believe in it. Bulgari was a shop in Via Condotti, which was pretty inaccessible. It was intimidating.” As if to affirm Mr. Gianni’s view, Andy Warhol had once described Bulgari’s Rome store as the “most important museum of contemporary art”. What he needed, Mr. Gianni felt, was a product with a profile that would break down the fear of the threshold he was seeing in customers he wanted to enter the world of Bulgari.

Could it be a watch?

“I was never really keen about watches,” he admits. “But I realised a watch might provide Bulgari with an accessible product, something recognisable that people would step into a very intimidating shop on Via Condotti for.” The watch was not an overnight success, but it did enough to convince Mr. Gianni to take his concept a step further. In 1977, he introduced the ‘Bulgari Bulgari’, the name a deliberate marketing ploy intended to emphasise that this was a watch that captured the essence of the company’s creative spirit. A flair move.

As with the Roma, the name was engraved around the bezel, only this time the lettering was evenly spaced, so the words ran seamlessly into each another. The design imitated the aesthetic of Roman coins, a historic motif the Bulgari family had played with before in jewellery. The Bulgari Bulgari also had a mechanical movement. And not just any mechanical movement, but one made in Switzerland. As a man of the world, Mr. Gianni was only too aware that if his watches were to have any credibility among the cognoscenti, they would need to be Swiss-made. He set up Bulgari Time, Write and Light in Geneva, which also made silver and gold pens and lighters. “It would have been inconceivable to make the watches here in Italy,” he says. “‘Swiss Made’ makes a watch more precious, especially when you export.” It would prove third-time lucky. ‘Bulgari Bulgari’, an Italian watch with a Swiss heart, was a hit — and for reasons that pleased Mr. Gianni. “It had immediate success without us really promoting it too much, because it was not expensive,” he says. “The trick of ‘Bulgari Bulgari’ was to make it accessible, readable, and a sort of ambassador of the Bulgari brand all around the world.” He remembers it costing a million Italian lire in steel, around $1,100 at the time, and more in gold. “That made it accessible by the standards of Bulgari, which at the time was perceived as very high-end,” he says. “It drew a lot of people in that would otherwise never have dared come into the shop.”

He returns to a familiar refrain. “But that’s it,” he says. “My legacy was just to make ‘Bulgari Bulgari’.” Can he be proud of it? “Yes, it was clever,” he says. “It was the appropriate thing at the appropriate time. And it will remain with Bulgari forever.”

Read the full story in Issue 90, available now.