THE MAN WITH NO FAME

Terence Hill’s career could be read as a story of what might have been. He is, after all, a Paul Newman lookalike whose finest work came in a character called Nobody. But that would be a mistake, for the Italian-born actor — still going strong in his ninth decade — has come to embody the best values of showbusiness.

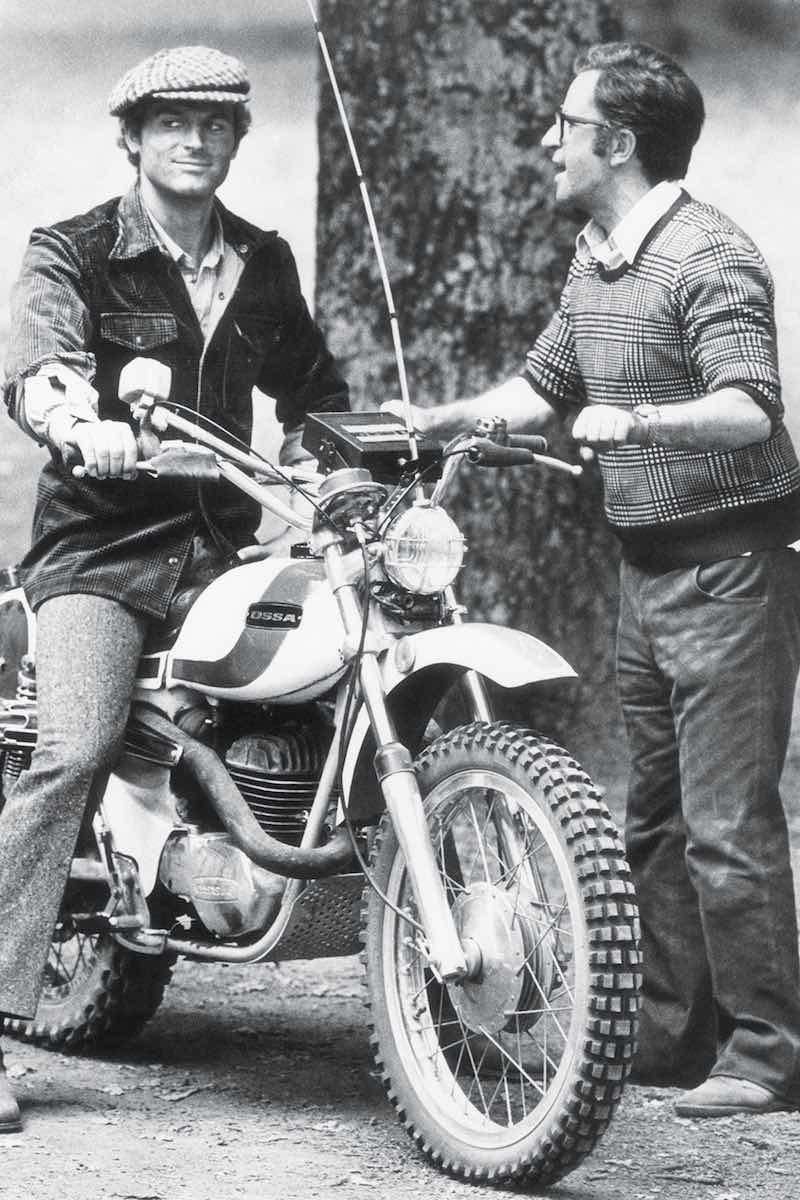

In January 1977, the Los Angeles Times dispatched a reporter to Almería in southern Spain, where an actor whose career was threatening to make an indentation in the U.S. market was shooting a Foreign Legion drama called March or Die. After spending some time on set, the reporter noted his subject’s good looks and easy charm. “This dashing rogue,” he wrote, “is a former watersports champion who keeps a complete gymnastics unit in the barn next to his home in the Massachusetts Berkshires and insists on doing all his own stunts.” On the question of personality, though, the Times — ironically or otherwise — decided to hedge its bets. “If he is going to be a big American star,” the story read, “he will have to stop fraternising with the extras and giving everybody who comes up to him a slightly nervous grin. [He] must learn to be tough and snarl at wardrobe people who fail to have the right costume ready when he needs it. Whoever heard of someone whose name is above the title sprinting back to his trailer to get a costume so the director can get one more scene in before the desert sun clouds over?”

The awfully obliging actor was Terence Hill. He was 37, at the height of his powers, and with a quarter of a century of movie experience already behind him.

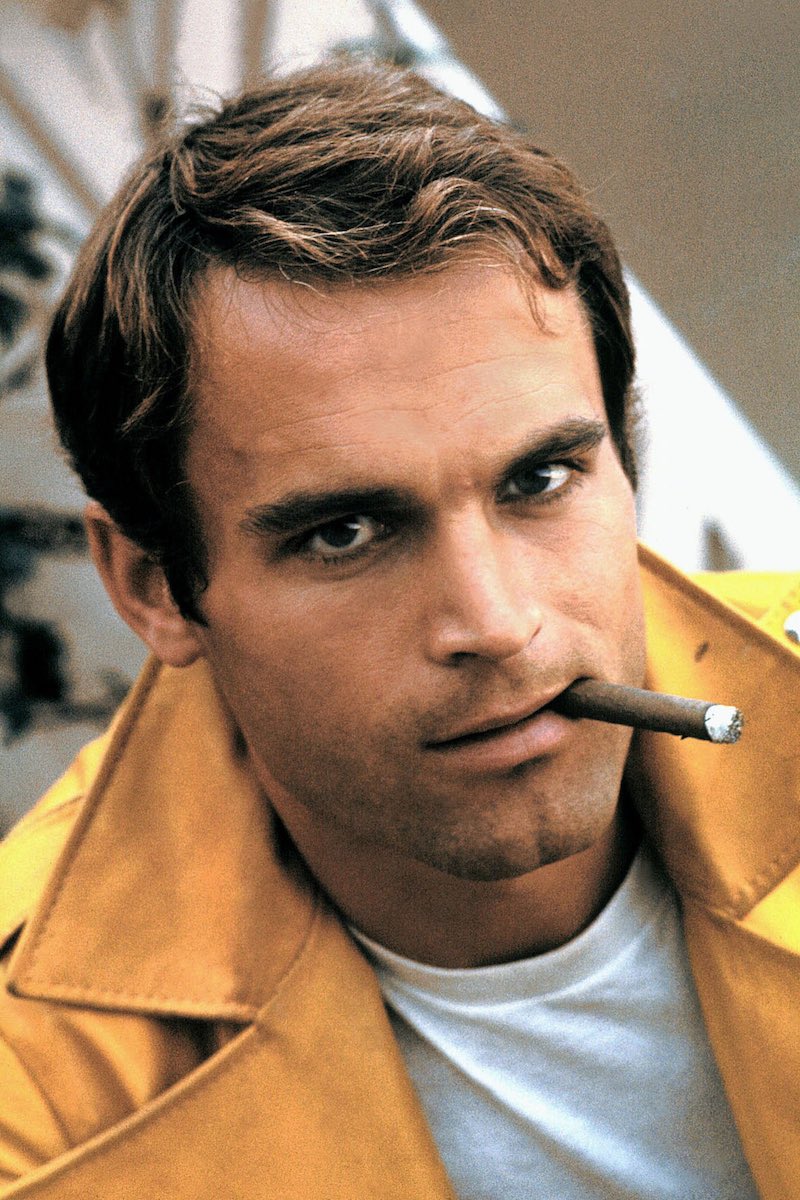

He’d fallen into the business in his native Italy as a child, and established himself in Europe in the sixties by meeting the appetite for spaghetti-western antiheroes set off by Clint Eastwood’s Man With No Name. Hill had even managed the curious feat of taking those blood-soaked archetypes and wrestling them into successful comedy westerns (replete with burp-gags and burlesque fistfights). Physically, as the L.A. Times would warn us, he was irresistible: straight-backed, blue-eyed, and feline of movement. A cleft in his chin helped delineate a beautifully symmetrical face, a face he has put to good use in the expressive, playful roles that have characterised much of his output across seven decades. He is a clone of Paul Newman, with added goofiness.

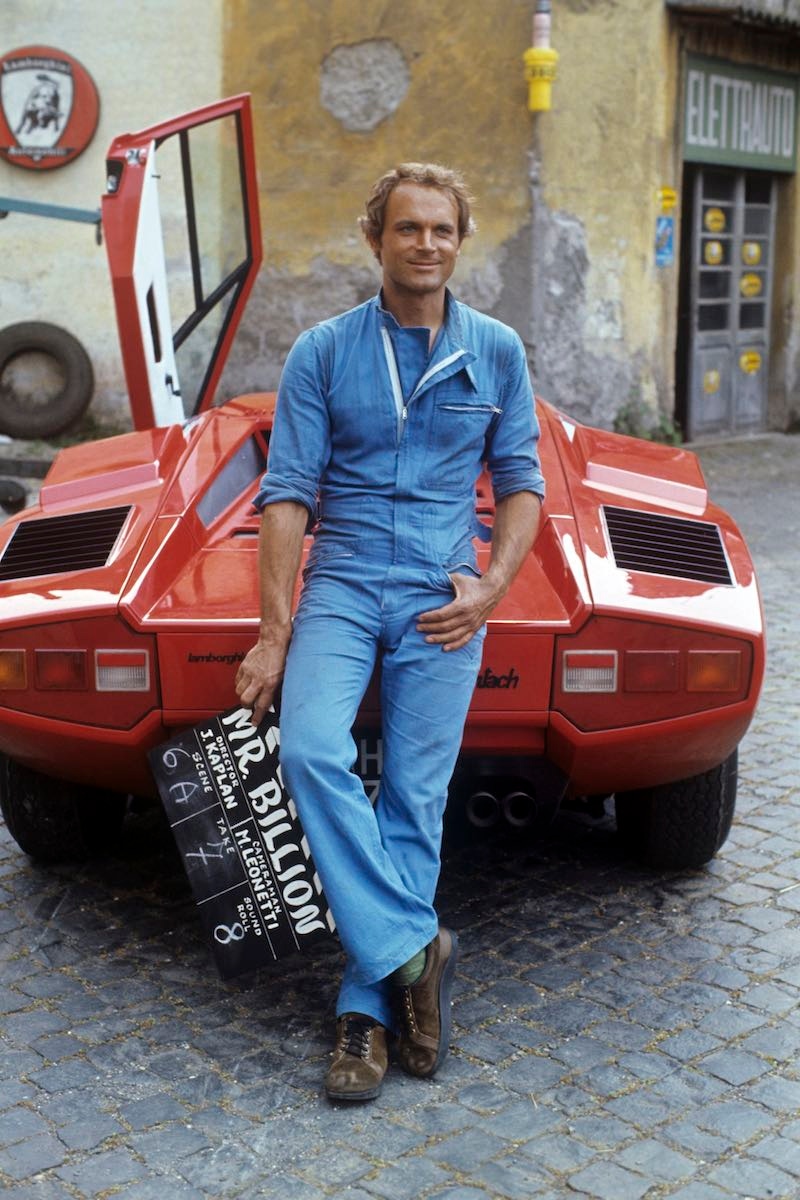

Yet March or Die, Hill’s Foreign Legion picture, was not well received in the U.S., and his debut as a lead in a Hollywood production — Mr. Billion, also from ’77 — went the same way. Those failures were not, to be sure, the end of his career: he hammed it up to great effect with his long-time amico Bud Spencer in a slew of buddy-action films that were forerunners to franchise monsters like Beverly Hills Cop. And to this day, aged 81, Hill is regarded as a monolith of T.V. and film in Italy. But widespread, commercial — read: American — acclaim eluded him. He is the man with two names who is afforded nothing more than minor-cult-like status. That he never made the leap to Hollywood invites speculation. Is it possible he was too nice? Could he have snarled at a few more wardrobe assistants along the way? Or is the only question worth asking, How much does it matter?

Witnessing Dresden

Hill was born Mario Girotti in Venice in 1939. His father was Italian and his mother German, a connection that prompted the family to move to Lommatzsch in Saxony when Mario was four. His parents felt they’d be safe in the countryside, but war nonetheless came to their doorstep with the bombing of Dresden, 20 miles away, in February ’45. Mario saw and heard the bombers flying overhead; his father, who was working in the city, survived unharmed, though the family was none the wiser for several days. Mario suffered nightmares for years afterwards.

They soon returned to Italy, and in post-war stability Mario’s path opened up for him. At his local swimming club, it turned out that one of his teammates’ parents was a production assistant to Dino Risi, the master of commedia all’Italiana. In 1951 a call went out for auditions for child parts in Risi’s next film, Vacanze col Gangster (Holiday with a Gangster): Mario and his mother went along, and Mario returned with a major role. From then on he was prolific — he used acting jobs to pay for his education — but it wasn’t as natural as it might appear from the present day. “I didn’t like it,” Hill told the Italian edition of Vanity Fair this year. “I was shy. Before entering the scene my heart reached 150 beats; I often got a fever. I had to do it — it was also good for my family.”

Read the full story in Issue 73 of The Rake - on newsstands now.

Available to buy immediately now on TheRake.com as single issue, 12 month subscription or 24 month subscription.

Subscribers, please allow up to 3 weeks to receive your magazine.