THE RIDE OF OUR LIVES

If the seas off Cornwall are full in September and October, something must be going on. Surfing, once a cultish pursuit associated with exotic locales, has gone mainstream, and its huge cultural wave is taking everyone with it. No wonder, writes JOSH SIMS in Issue 48 of The Rake when the idea of a board and a wave embodies the dream of escape and an endless summer…

“Some kind of osmosis takes place,” says Barry Haun. “You wait maybe hours for seconds of a wave, and you’re willing to pound into a freezing, mid-winter ocean to get those seconds. If procreation depended on the same kind of enthusiasm, we’d have all died off.”

Barry Haun has been surfing, he says, “since ’72” — the golden summer of his memory — and is now happy to be the creative director of S.H.A.C.C., the Surfing Heritage and Culture Center, in California, which receives thousands of pilgrims every year. It’s here that he looks after the centre’s collection of more than 600 surfboards — probably the world’s best, including early wooden boards, four attributed to the sport’s spiritual founder. “We get offered a lot of boards,” he says. “But, you know, everyone thinks their board is the Mona Lisa. But invariably they’re not.”

Compare, though, the likelihood of anyone thinking of their old tennis racquet as a work of art, or their football boots. To mount a surfboard on your wall and call it a sculpture is not a preposterous idea. Indeed, from graphic design to movies, music to fashion, even to language — ‘wipeout’, ‘riding a wave’ — surfing has had a remarkable cultural resonance beyond the activity itself.

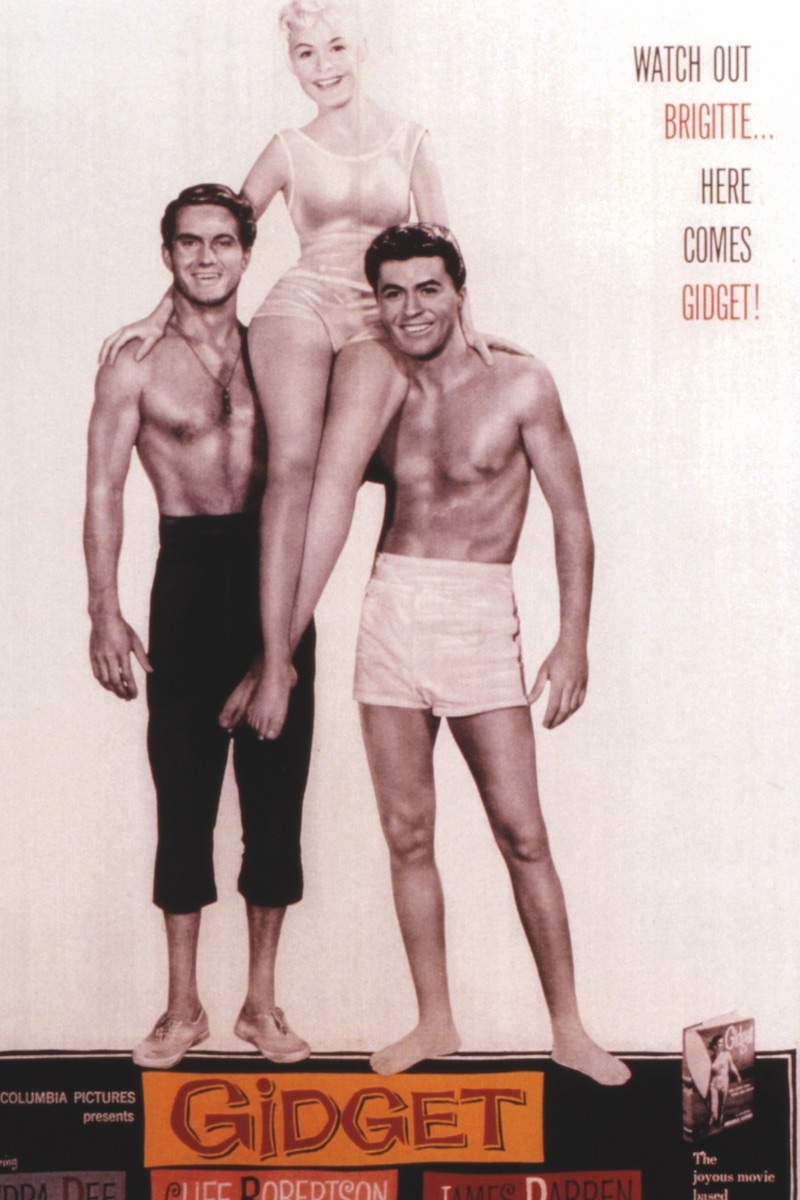

Think of surfing and, even if one lives in a snowbound city in a land-locked country, one conjures up a self-consciously free and easy lifestyle and the saturated colour of an Elvis film, like 1961’s Blue Hawaii (a role for which Presley had to spend many hours under a tanning lamp in preparation) or perhaps Sandra Dee’s Gidget (1959), the movie that gave us the image of the surfer as laid-back to horizontal. Then there are the surf-ploitation flicks, like Beach Blanket Bingo, The Horror of Party Beach and, yes, How to Stuff a Wild Bikini.

Or one hears the Pendletones — a group named after the Pendleton over-shirt that surfers wore to warm up after a spell in the water — who were renamed the Beach Boys, their early hits, such as Surfin’ Safari, ‘Surfer Girl, Surfin’ U.S.A., driving a genre of surf music that gave the world the likes of The Surfaris and ‘surf guitarist’ Dick Dale. Such media rode the cultural wave, so to speak, but also transmitted it, making surfing symbolic even for those who would never see it, let alone do it.

One might be tempted to see the sixties’ explosion in surf culture — its exoticism, its fantasy, its promise of escape from the grind, or of life off the grid — as a welcome antidote to the grim realities of the Cold War. It certainly helped that among celebrity surf fans of the time were the likes of Richard Boone, Peter Lawford and Lawford’s influential friend John F. Kennedy.

“But surfing has always had this special appeal, even to people who lived nowhere near the sea. It embodies the endless summer — blue water, long beaches, California. And I speak as someone who lives in California. And that fantasy element is as resonant now as it ever was,” says Peter Neushul, surfer, senior researcher in history at the University of California, and co-author of World in the Curl: An Unconventional History of Surfing (Random House). “Surfing always seems to happen in this beautiful setting,” he adds. “If you’re sitting in rainy England, it’s not hard to see how the likes of, say, Baywatch would make you want to be there. Surfing was never all positive — you get to interact with a lot of sewage — though when it’s good it really delivers. You remember the best days the rest of your life. But it’s also been marketed beautifully with a lot of beautiful people.”

It was, if you like, the more positive, upbeat, upmarket alternative to skateboarding, which grew out of surfing via an aptly named New Wave punk scene and took on a more urban, grungier aesthetic. But, of course, surfing predated skateboarding as well as the 1960s, not just by decades but by millennia — four of them, in fact. Ancient Hawaiians, the earliest known practitioners of surfing, literally prayed for good surf in order to do what they called he’e nalu, or ‘wave sliding’, both for recreation but also as a form of conflict resolution. Kings surfed. Captain Cook wrote about it. It was also Cook — leading the colonisation of Hawaii, leaving rampant syphilis, and installing work on sugar plantations that left little time for the waves — who arguably saw surfing in the modern era ultimately founded on the decimation of an island race and culture.

It quickly caught the collective imagination, though. Artists documented surfing — the first work of Europeans depicting a surfboard, View of Karakakooa, was published in 1790. In his 1872 novel Roughing It, Mark Twain wrote admiringly of seeing a Polynesian who “at the right moment would fling his board upon the foamy crest and himself upon the board, whipping by like a bombshell”.

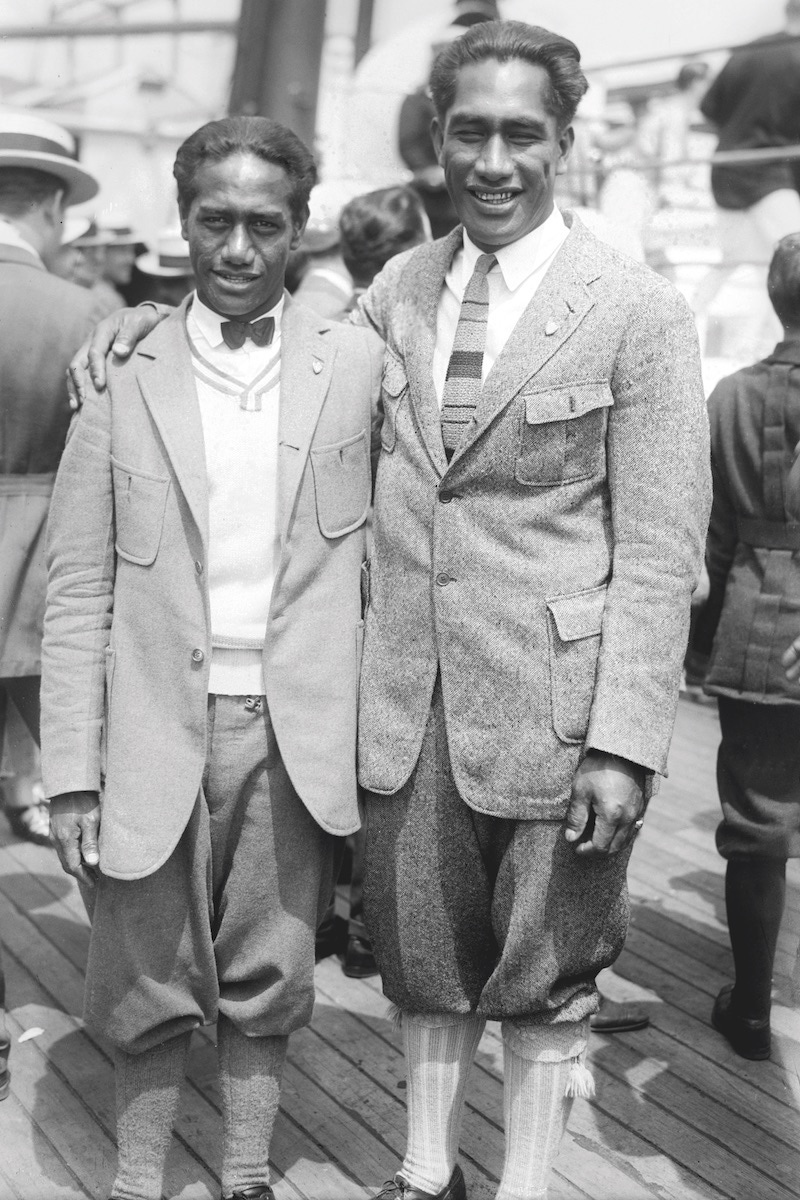

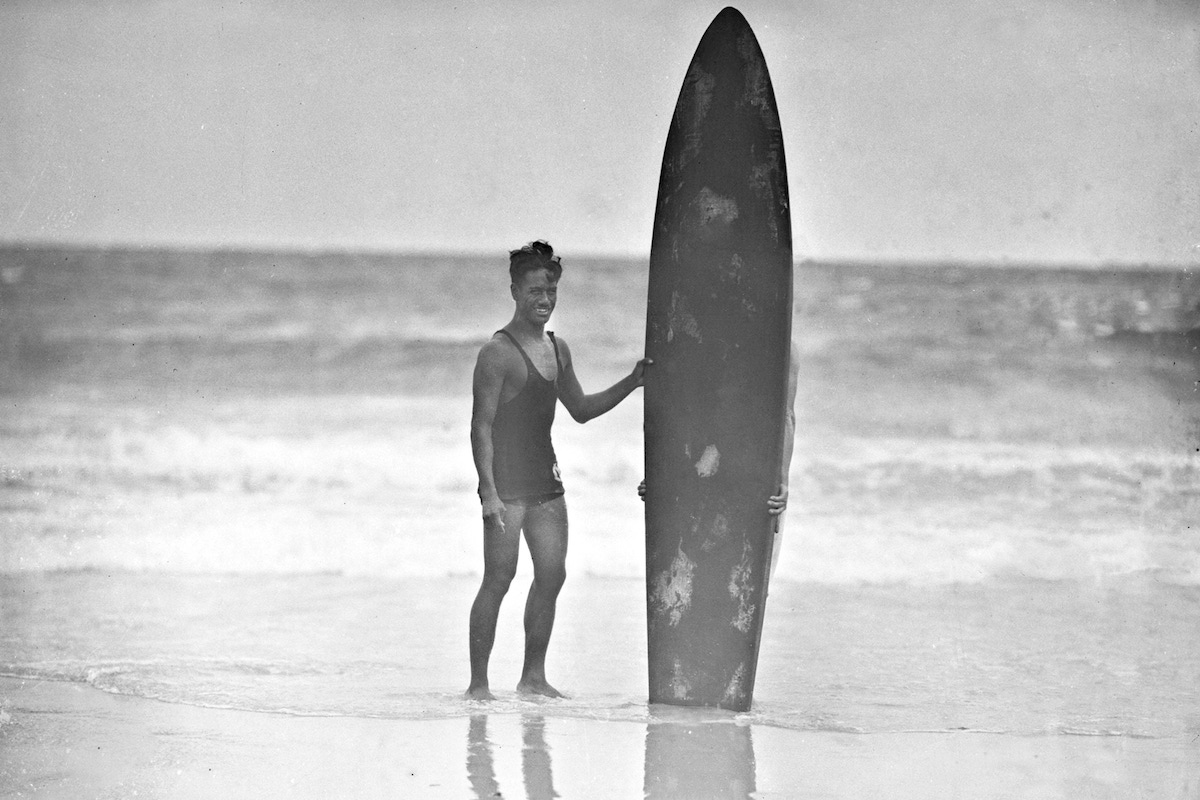

Yet it wasn’t until the early 1900s that surfing escaped its pigeonhole as an esoteric native practice, when a bunch of teenagers, the so-called Beach Boys of Waikiki, sparked renewed interest. That was boosted by surfing’s first appearance on the American mainland, when Hawaiian George Freeth cut the traditional 16-foot board down to a more manageable six-to-10 feet, moved to California and, as its first lifeguard, also became the first sponsored surfer, promoting the Pacific Electric railroad’s new beach line. But it was Duke Kahanamoku — Olympic gold medal swimmer, “the greatest surfer ever, the greatest there ever will be,” according to Neushul, and the sport’s aforementioned spiritual leader — who in 1915 took surfing international, notably by exporting it to Australia and setting that nation on its way to becoming the surfing superpower. By 1928 surfing had its first major competition.

With U.S. servicemen based in Hawaii over the following decade as well as during the second world war, it was, somewhat contrary to surfing’s peace and love image, military technology that helped make the sport viable for the many rather than the few who, like Kahanamoku, had freakishly long hands and feet. Many a scientist at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) also surfed. Gerard ‘Jerry’ Vultee, aeronautical engineer and co-designer of Amelia Earhart’s Lockheed Vega, inspired the first hollow boards; Bob Simmons, mechanical engineer, brought fibreglass, foam and hydrodynamics to surfboards; Walter Munk, also at Caltech, was the father of wave forecasting; Hugh Bradner, who worked on the Manhattan Project, devised the modern neoprene wetsuit, allowing year-round surfing for the first time. Each development advanced surfing’s popularity.

No wonder big business was never far behind in riding the wave, too. The tourist industry on which Hawaii became increasingly dependent recognised the value of surf kitsch. In the 1950s, Dale Velzy became the sport’s first major sponsor, giving boards to surfers in exchange for endorsements, and he was the first board manufacturer to launch a wide-scale advertising campaign, too. Fashion — ironically, perhaps, given how little is worn while surfing — quickly followed suit. It was a ‘mom and pop’ tailoring shop in Hawaii by the name of M.Nii that first made surfing a matter of style. Its Makaha trunks — named after the Hawaiian surf mecca — rapidly inspired a clothing industry, with surf shorts the thing to wear anywhere near water.

Soon after, swimwear company Jantzen struck the first formal endorsement deal with a surfer, Ricky Grigg, while fabric advances saw the likes of Hang Ten devise the first fast-drying nylon shorts. All bar the most artisanal of board makers — or ‘shapers’, as they’re called — parlayed their reputation into the launch of clothing lines and accessories. The music, the movies, the magazines — the likes of John Severson’s pioneering Surfer — all followed, ensuring the underground was quickly overground, and more frequently on dry ground than not. Everything surf became a signifier of the dream of freedom.

“There’s this idea of the endless summer attached to surfing that was and still is just a very attractive vision,” says Haun. “It lends itself to celebration. Soccer is by far the biggest sport in the world. But can you name five songs about soccer?”

That celebration, inevitably, would be co-opted by global brands as diverse as Coca-Cola, Motorola and Chevron in advertising that would underscore surfing’s romantic image (Citroën’s latest car is the ‘Cactus Rip Curl’). But that celebration was not entirely without taint. Running in parallel with the upbeat, sun-kissed, Brian Wilson vision of surfing was, historically, always one that emphasised an alternative, bohemian, drop-out ‘soul surfing’ culture that made it more exclusive than inclusive, one that saw surfers as little more than bikers with boards. In the 1960s, the Brotherhood of Eternal Love was a crew of Californian surfers who just happened to also run one of the country’s biggest drug-smuggling operations, thus helping to shape the decade in other ways, too.

The sport’s inherent danger also played to this other image. There is what lies beneath, of course: “While you feel connected to the water when surfing, it’s still this frontier with creatures that, should you come across them, will eat you,” Neushul says, and it is a theme that movies, such as this year’s The Shallows, still play on. And there is the daredevil spirit — the fad for chasing ever bigger waves has seen more surfers killed in the past 15 years than in the previous four decades combined.

“Surfers in the early days were not looked on kindly,” Haun says. “In fact, my parents still ask me when I’m going to quit ‘this surfing thing’. That counter-cultural aspect led surf culture to be perceived negatively in a way that is still sometimes the case — look at Point Break. Surfers are typically portrayed as being either thuggish or as Neanderthal slackers. And surfers still tend to think of themselves as rebels, even if they’re all rebels at the same time.”

Surf culture, ever evolving, is not without its more particular problems today, either. Neushul notes — ironically, given that its greatest heroes were men of colour — that it is now overwhelmingly a white middle-class activity (he contends because to surf you need to swim, and access to pools in poor black neighbourhoods in the U.S. is woefully lacking). For all that surfing tends to present itself as the sporting side of environmental activism, few surfers, he says, are really engaged. There is still plenty of localism — surfers territorial over their local beach to the point of threatening visitors, as, most famously, did Australia’s Cronulla surfers with their “we grew here, you flew here” body paint. And, some might say, there is too much money in it — increasingly surfing is about selling clothes, lots and lots of clothes, about weathering the peaks and troughs of a baggy, flip-flopped fashionability that can see the likes of Quiksilver become a giant and then go bankrupt.

“There are plenty other sides to the sport that it doesn’t really want to hear about, too,” Neushul adds. “Surfing is an incredibly sexist sport, for example. Pick up a surfing magazine and all you’ll see is a woman’s butt. It’s like ice skating: does a woman win a competition because she’s the best surfer — and there are plenty of women out there who can ride the same wave any man can — or because her behind looks good in a wetsuit? Sunny surfing still has this dark side.”

Yet surf culture is only going to get bigger, in part thanks to the ambassadorship and elite athleticism of pro surfers like Kelly Slater and Laird Hamilton. Through a combination of competition, coverage, commercialism and cool, surfing has gone through a radical image overhaul in recent decades.

“That change from subculture to the mainstream over the last 15 or so years has been incredible to watch,” says Richie Jones, marketing director of British surf brand Saltrock. “Surfing off Cornwall in sub-zero temperatures used to single you out as very strange, but not any more. Now all the kids who grew up with free-sports — skateboarding, snowboarding, mountain biking, surfing — are old enough to be passing that interest on to their kids. I used to have long hair and owned numerous VWs. But the surfer dude has been gentrified. You see whole families dressed in Saltrock, which epitomises how mainstream surfing has become. They’re buying into a beach lifestyle.”

In recent years surfing booms have been seen in younger markets, including Indonesia, the Philippines and South America. Technologies continue to allow for faster, longer, easier rides. This summer surfing was confirmed as an Olympic sport for Tokyo 2020. And Haun even suggests that it will continue to find invigoration through new kinds of hybridisation, all the more so given that surfing — via wave pools — is finding popularity with people who live nowhere near the ocean “and, what’s more, with no interest in surfing in the ocean either”. He offers ‘redneck surfing’ as a possible name.

That may not catch on. But in the meantime, surfing remains ineffably alluring: the beaches and bikinis, the white horses and bronzed bodies, the thrills and spills, the blend of wild communion and extreme competition. Like the dream wave, it’s larger than life.

Originally published in Issue 48 of The Rake.

Subscribe and buy single issues here.