THE SHEER GAUL

He possessed — still possesses, in fact — an acerbity that makes Liam Gallagher look like Nick Drake. Originally published in Issue 43 of The Rake, Stuart Husband writes that Jacques Dutronc, the Mod dandy with a singular place in French rock history, oozes so much charm and savoir-faire that even when he’s mocking you, it feels all right …

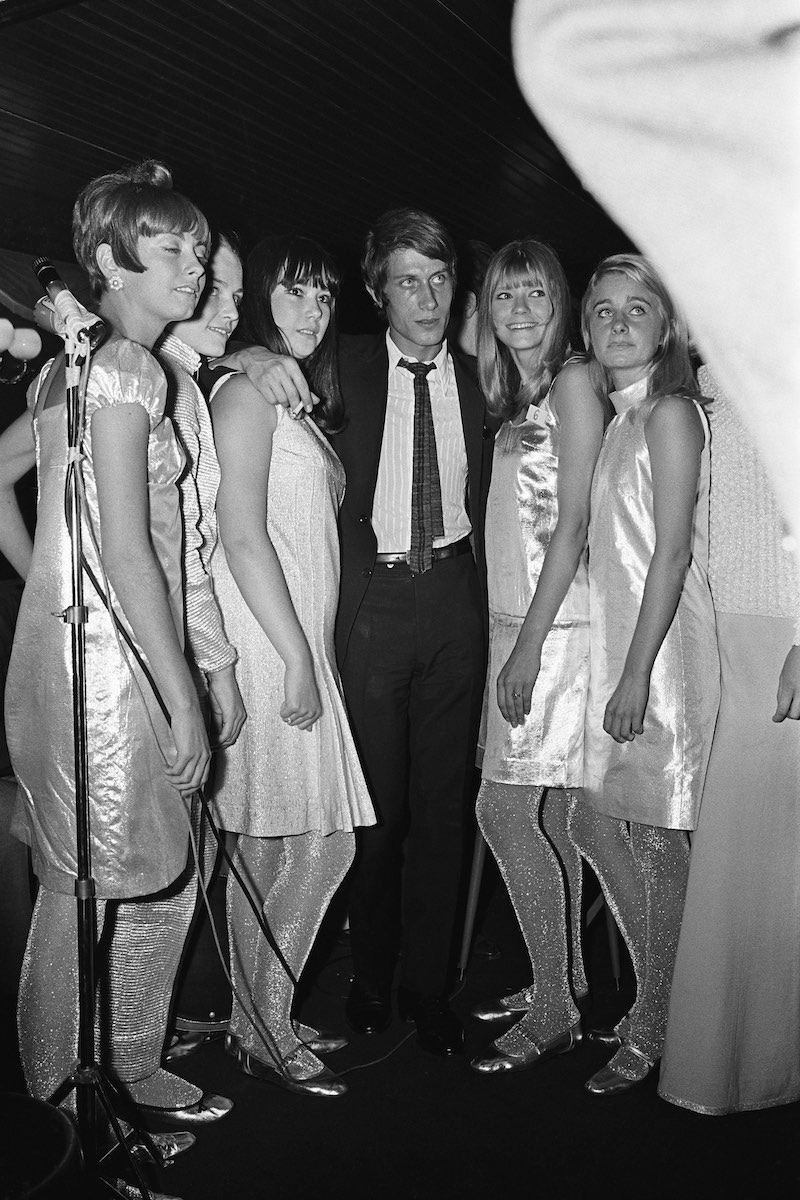

In 1966, the magazine Paris Match photographed Jacques Dutronc in a less-than-unenviable position. He is reclining on a bed in the offices of the Catherine Harlé modelling agency in white polo neck and black mohair trousers, encircled by a phalanx of the agency’s top signings, who proffer bowls of fruit and champagne cocktails like votive offerings. Dutronc had just referenced the Harlé agency in his single Les Playboys, which spent six weeks at No.1 and sold 600,000 copies; it was a hipster salon in 1960s Paris with It girls such as Anita Pallenberg, Nico and Anna Karina on its roster, and various photographers, filmmakers, Rolling Stones and members of Warhol’s Factory passing through and crashing on its couches. Here, in the centre of it all, supine and supreme, is Dutronc, looking like the proverbial chat who got la crème.

In fact, Les Playboys, like all Dutronc’s songs, is less a celebration of its swinging era and more a sardonic take on its cant and excesses. The barbed lyrics, delivered with an acerbity that makes Liam Gallagher sound like Nick Drake, dismiss the playboys — “Habillés par Cardin et chaussés par Carvil” — and their allure, because Dutronc has a secret weapon that makes girls fall to their knees — and we’re made aware, by the lubricious way he sings “Un joujou extra qui fait crac boum hu” that he’s not talking about a mere pistolet à bouchon. This bring-it-on attitude, coupled with his elemental garage-band sound, gave Dutronc a singular place in the French rock superstar pantheon, less chanson-indebted than Serge Gainsbourg, more winningly outré than Johnny Hallyday (an early acquaintance). Dutronc’s closest stylistic soul-brother is probably The Kinks’s Ray Davies, a fellow contrarian, pop-culture classicist, cigar smoker, and impeccable Mod dandy. But even Davies never got to marry Françoise Hardy. “I’ve been lucky,” Dutronc has said, in his nicotine-inflected drawl. “But,” he tends to add, “you make your own luck, right?”

Dutronc is the archetypal Parisian flâneur. He was born in the 9th arrondissement in 1943 to a staunchly bourgeois family. By the early sixties he’d dropped a graphic design course in favour of cutting an enigmatic figure around Le Golf-Drouot, a tea room (complete with miniature golf course, hence the name) turned rock club, where he surveyed the world with quizzical detachment from his rarefied De Gaulle-esque height and played guitar in El Toro et les Cyclones (which wasn’t even the worst offender among contemporary band names, as Hector & Les Mediators or Gil Now & Les Turnips might attest).

After two years of compulsory military service — not a great fit for the recalcitrant Dutronc, one suspects — he returned to secure a job as an arranger and songwriter at Vogue records, the label of choice for the nascent French rock and ye-ye movements. One of the label’s biggest hits was an E.P. by a proto-Dylan-ite folkie named Antoine, called, rather grandly, Les Élucubrations d’Antoine. One day, Dutronc was ostentatiously snubbed by Antoine in the company elevator, and his response was to join forces with a recently hired lyricist named Jacques Lanzmann (a writer and editor of Lui, France’s answer to Playboy, as well as the brother of the documentary maker Claude Lanzmann, director of the epic Holocaust meditation Shoah) to write Et Moi Et Moi Et Moi, a sprightly takedown of the beatnik solipsism of Antoine and his ilk, in which the “sept cent millions de Chinois” and the singer — “avec ma vie, mon petit chez-moi, mon mal de tête, mon psy” — are accorded equal significance, at least in his own estimation.

Et Moi Et Moi Et Moi became one of the biggest hits of the decade, and Dutronc followed it with equally witty J’Accuse-style broadsides, including Mini Mini Mini, in which he laments the diminution of culture and declares his against-the-grain preference for the maxi, from hemlines downwards (“Maxi-moke et maxi-jupe, maxi-moche et maxi-pute”), and Les Cactus, a roiling stomp both vaguely menacing and thoroughly absurd, in which the titular succulent becomes a metaphor for a harsh and unforgiving world, or possibly just a nagging haemorrhoidal condition (“Le monde entier est un cactus, Il est impossible de s’asseoir”). His 1966 debut album sold more than a million copies, helped by nods from Georges Pompidou (who inveighed against his former finance minister Valéry Giscard d’Estaing as, “dans les mots de Jacques Dutronc, un cactus”) and Guy Debord, the presiding deity of Situationism (who denounced Dutronc as a hooligan, much to his delight).

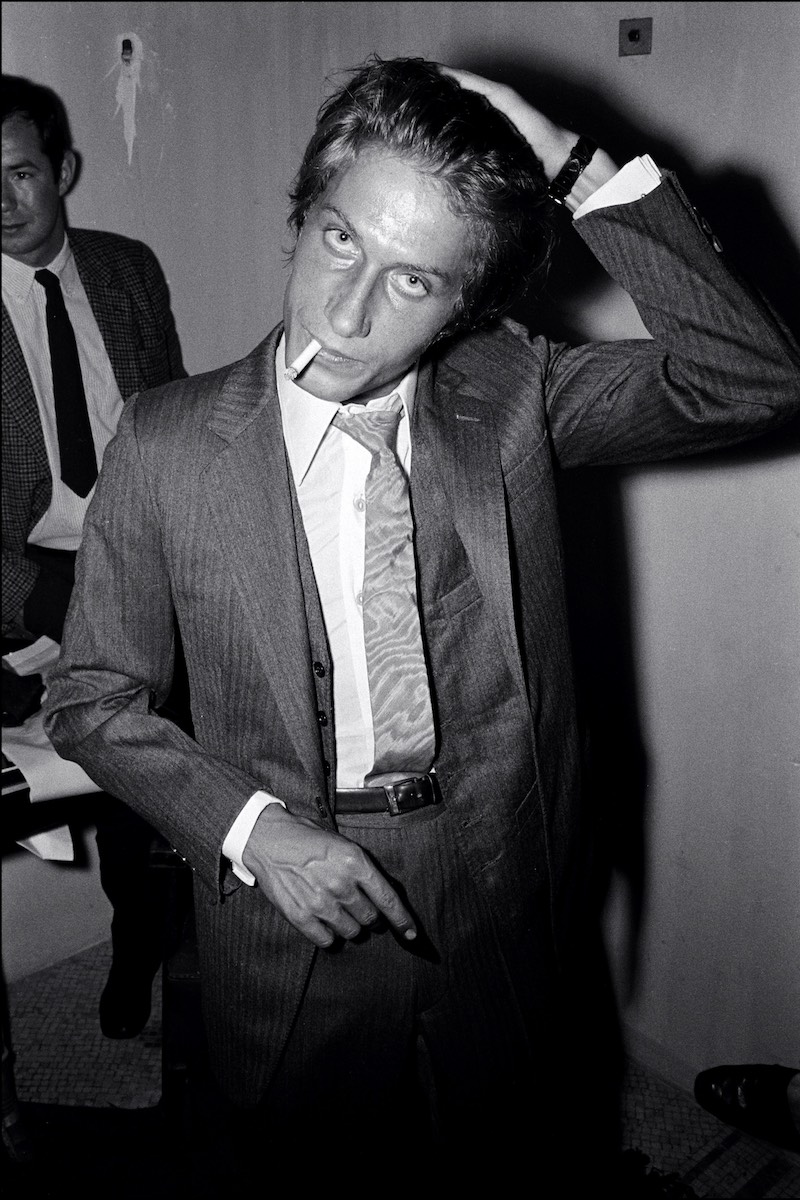

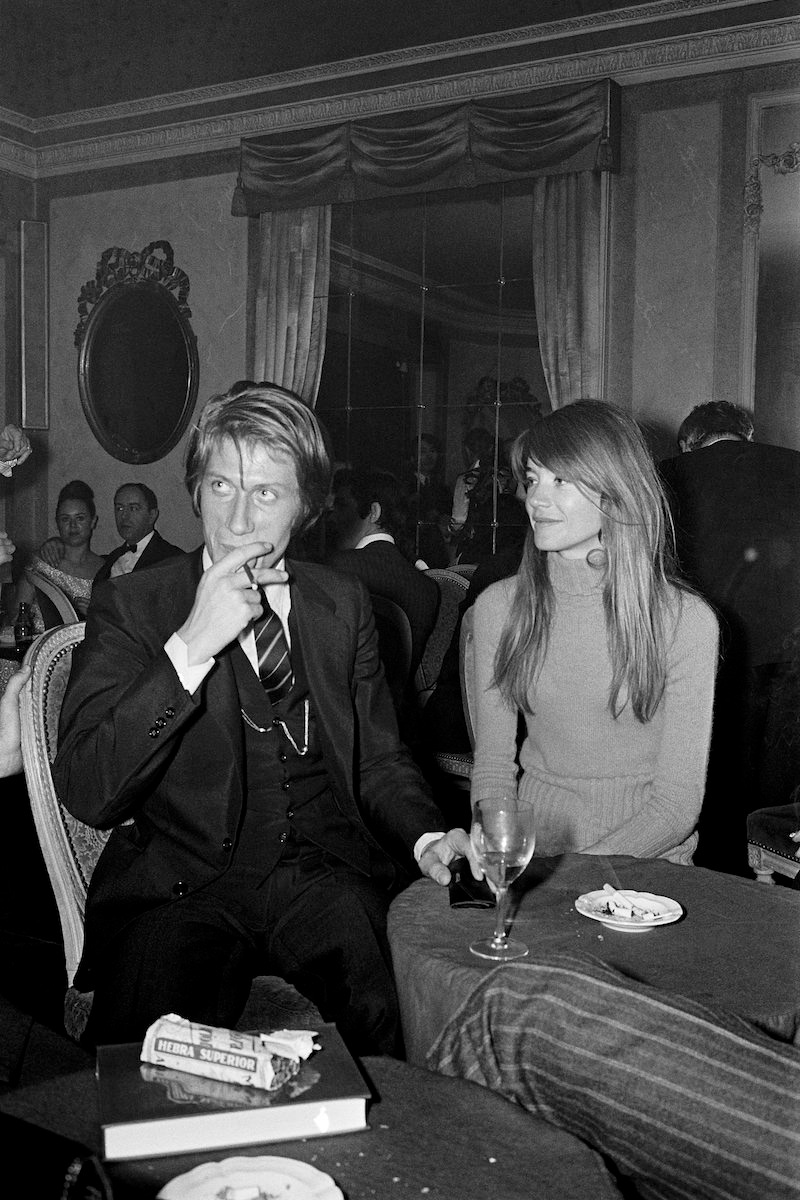

If Lanzmann’s lyrics set the tone for the creation of Dutronc’s caustic persona, the latter alone was responsible for his sharp-yet-louche look. He shunned what one of his best-known songs described as the ‘Hippie Hippie Hourrah’ in favour of classic three-piece suits, Chelsea boots, and an insouciant Mod quiff. The suits came from Renoma, a hip menswear boutique opened by Maurice Renoma in Paris in 1963 and also known as the White House, where you might bump into anyone from Salvador Dalí to Jean-Paul Belmondo in the fitting rooms, and which popularised a distinctly French sixties suit silhouette — high posture, flared skirt — that Dutronc, with his commanding stature, carried off with aplomb. His astringent-boulevardier image, complete with ever-present lofted cigarette or cigar, was enshrined with the help of his friend Jean-Marie Périer, a photographer for the trend-surfing music magazine Salut les Copains.

“Jacques had an insolence,” recalled Périer, “so loose, so almost aggressive, that all the singers used to go and look at him and what he was doing on stage.” Dutronc once played a charity show attended by d’Estaing when he was president, and was asked what he thought about performing for him. “And Jacques pushes the president,” said Périer, “and says to the crowd, ‘I fuck him like a rat at the pinball machine!’” But, like his friend Gainsbourg, Dutronc had a strong streak of tendresse alongside his talent for subversion. In J’aime Les Filles, he enumerates his Catholic tastes when it comes to the opposite sex (“J’aime les filles de chez Renault/J’aime les filles de chez Citroën/J’aime les filles des hauts forneaux/J’aime les filles qui travaillent à la chaîne”), while his biggest hit, Il est cinq heures, Paris s’éveille, is an evocative love letter to the exotic night owls of the French capital (“Les travestis vont se raser, Les stripteaseuses sont rhabillées”) complete with, of all things, a flute solo. Little wonder that men wanted to be Dutronc, while women wanted to be near him, preferably in a state of déshabiller profonde.

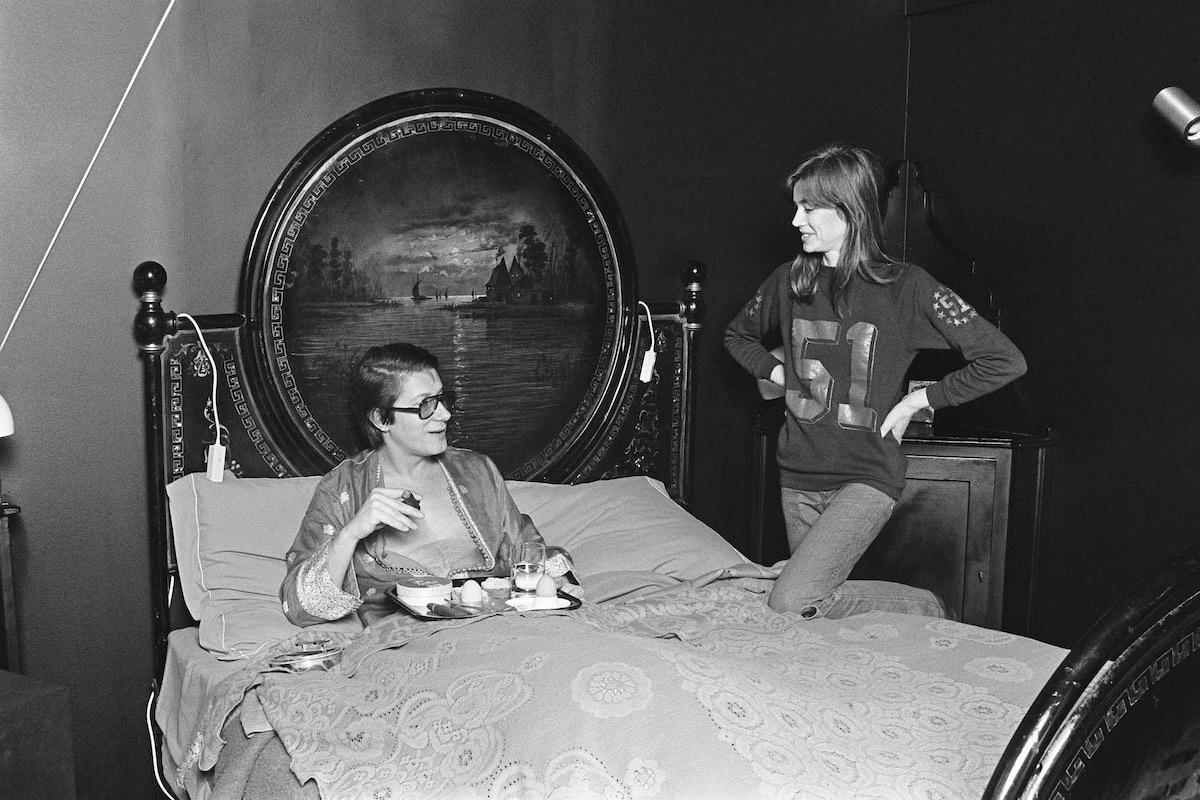

By 1967, however, Dutronc had already begun a relationship with his label mate and the most ‘It’ of the French It girls of the sixties, the impossibly cool Hardy (in fact, he stole her away from his friend Périer). For the French tabloids and gossip magazines, their union has been the gift that keeps on giving, through the birth of their son, Thomas, in 1973, and their eventual marriage in 1981 (“for the tax breaks,” said Hardy, deadpan), to their current separated-but-not-divorced status. Hardy, like the rest of the French nation, tends to regard the latter-day Dutronc with a mixture of eye-rolling exasperation and doting indulgence.

Since Dutronc’s heyday, there has been plenty of call for both. His post-sixties musical output has been wildly erratic; for every mature classic like the cool, collected Le Petit Jardin, there have been adolescent embarrassments like the ill-advised yodelling on L’Hôtesse de L’Air or an album he did with Gainsbourg in 1980 called Guerre et Pets (War and Farts). Luckily, he’d begun an acclaimed acting career in the seventies, with box-office hits such as That Most Important Thing: Love (he later confessed to an affair with Romy Schneider, his co-star). He went on to win a Best Actor César for his craggy, searing portrayal of the title character in Maurice Pialat’s 1992 film Van Gogh (sadly, he never got to play René Belloq in Raiders of the Lost Ark, a role that Steven Spielberg, reportedly considering Dutronc the best French actor of his generation, wrote with him in mind, because his English wasn’t up to snuff).

Today, Dutronc lives in splendid exile in the town of Monticello in Corsica, with a harem of felines (up to 30 at the last count, which would require numerous cartons of crème). Like his old mucker Gainsbourg, he’s become the kind of magnificent ruin frequently wheeled on to ‘enliven’ those interminable television chat shows the French seem so keen on (and he’s lost none of his diplomatic skills: he recently opined that he’d rather have Ségolène Royal, then campaigning to be France’s first female president, not in the Élysée but “in my home, with me and my mates”). But the glory of Dutronc’s impudent-blade pomp is always ripe for periodic rediscovery. He’s referenced in Cornershop’s Brimful of Asha (“Jacques Dutronc and the Bolan Boogie/The Heavy Hitters and the chi-chi music”) and lionised by contemporary Modfathers such as Paul Weller and Miles Kane. In fact, the latter has come as close as anyone to nailing the appeal of Dutronc’s truculent savoir-faire. “There’s a photo of him standing somewhere with a ciggie,” Kane told one interviewer. “It’s all about how he wears a suit and that swag with it … It’s less about fashion and more about feeling, right? He had the stance, the extra va-va-voom.” Even Dutronc might find it hard to cock a snook at that assessment.

This article originally appeared in Issue 43 of The Rake.