THE WILD WHIRLWIND OF MUSTIQUE

Colin Tennant was the mercurial British aristocrat who, with a little help from Princess Margaret, made the island of Mustique a byword for high-society escapism. His character earned him comparisons to Prospero — and a reputation for controversy.

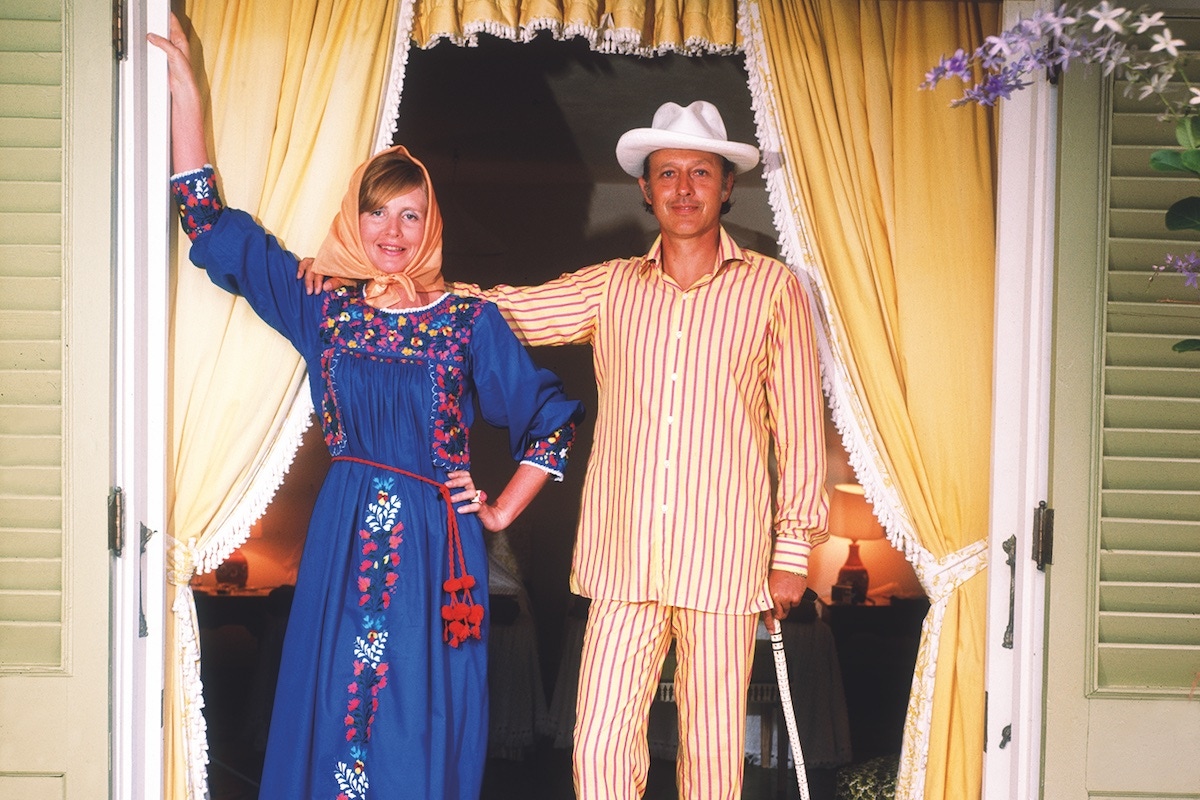

Towards the end of 1976, Colin Tennant threw himself an elaborate 50th birthday celebration on Mustique, the Caribbean island he had bought on a whim nearly two decades before. The week-long carousing culminated in a party billed as a latter-day Field of the Cloth of Gold; Macaroni Beach, the island’s finest bay, was decked out like Croesus’s palace. The trees and grass had been sprayed gold, while guests processed through triumphal arches made of plaited gold palm fronds. Princess Margaret, Tennant’s great friend and fellow Mustique resident, sported a gold kaftan and matching turban; Bianca Jagger was resplendent in a gold Scarlett O’Hara-style hooped dress with matching parasol, while Mick, in slashed shirt, cut-off jeans and straw hat, resembled a gilded Davy Crockett. The host presided in a tight satin suit laced with golden paisley whorls and starbursts. But they were all upstaged by the local boys, whose oiled bodies were draped in gold tinsel cloaks accessorised with codpieces made of gold-sprayed coconut shells. The latter may have particularly caught the eye of the photographer Robert Mapplethorpe, there to shoot the party on commission for Interview magazine. “Colin’s made himself a kingdom over here,” he wrote to his lover and patron, Sam Wagstaff. “Everyone changes their clothes at least three times a day. It’s the perfect place to wear your jewels. The whole thing is completely mad.”

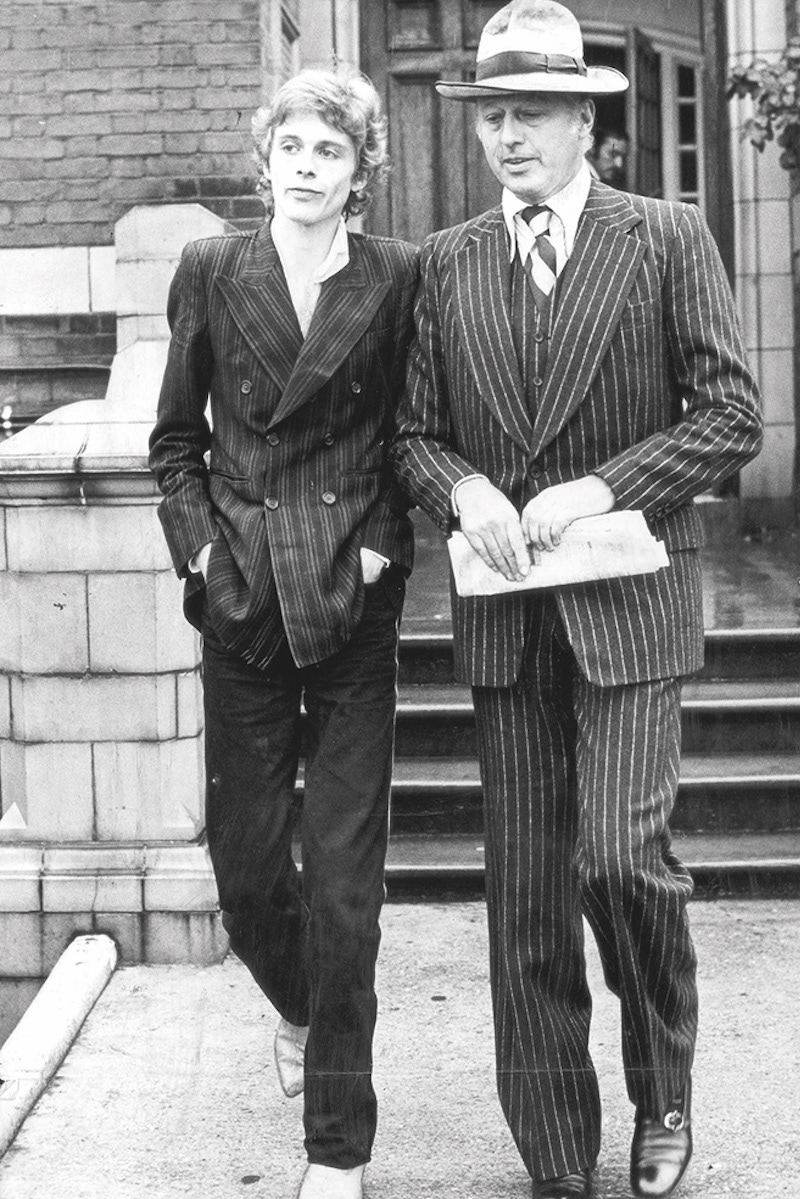

Such revels, by no means untypical of Tennant’s reign on an island whose name became a byword for a kind of louche seventies jet-set glamour, earned him comparisons to Prospero, Shakespeare’s mercurial magus in The Tempest; Nicholas Courtney’s official biography of Tennant, Lord of the Isle, begins with an epigraph from the play. In truth, Tennant, the 3rd Baron Glenconner, was a combustible mix of the play’s ‘airy spirit’ Ariel — he had no head for business, and burned through the family fortune indulging in everything from Indian antiquities to ill-advised property deals — and the feral, typhonic Caliban. “He wore controversy round his neck like a talisman,” wrote Courtney, “and liked causing a stir.” His legendary tantrums, “seizure-like in their sudden arrival and ferocity”, according to the writer Ian Jack, could be triggered by anything from tardy service (once, kept waiting for a drink at a bar in St. Lucia, he threw all the tables and chairs over the balcony into the sea) to a simple failure to get his own way; when he was refused a flight upgrade to join Princess Margaret in first class, he lay in a foetal position in the economy aisle and wailed and screamed until he was manhandled off the plane. British Airways subsequently banned him for life. “If you hitched your wagon to Colin, your life would be changed,” wrote Courtney, who served as the general manager of Mustique in the seventies. “But it could be a very wild ride.”

From the start, Tennant declared himself secure in his own status — “I have never been a social climber,” he said, “as I was born at the top” — while displaying a restless, if not skittish, nature. ‘Do keep up’ was his constant mantra, as friends, business partners and underlings alike trailed in his frenetic wake. While he breezed through academic life at Eton and Oxford, he was deeply affected by the divorce of his parents, Lord Christopher Glenconner and Pamela Paget, when he was nine. “It taught me never to rely on other people’s affections,” he later recalled. “What was being repressed was very damaged and quite neurotic.” After a spell in the Irish Guards, he went to work for one of the many family firms, the metal brokers and chemical traders C. Tennant Sons & Co, but it quickly became apparent that his true talents lay elsewhere. “His greatest gifts were the art of conversation and a flair for giving wonderful parties, both inherited from his mother,” Courtney wrote.

Read the full article in Issue 76 of The Rake - on newsstands worldwide now.

Available to buy immediately now on TheRake.com as single issue, 12 month subscription or 24 month subscription.

Subscribers, please allow up to 3 weeks to receive your magazine.

Our customer service team can assist with any subscription enquiries at shop@therakemagazine.com.