The Art of Saying 'No'

Saying 'no' is ultimately an expression of freedom, but also of power. The Rake explores the men who mastered the art.

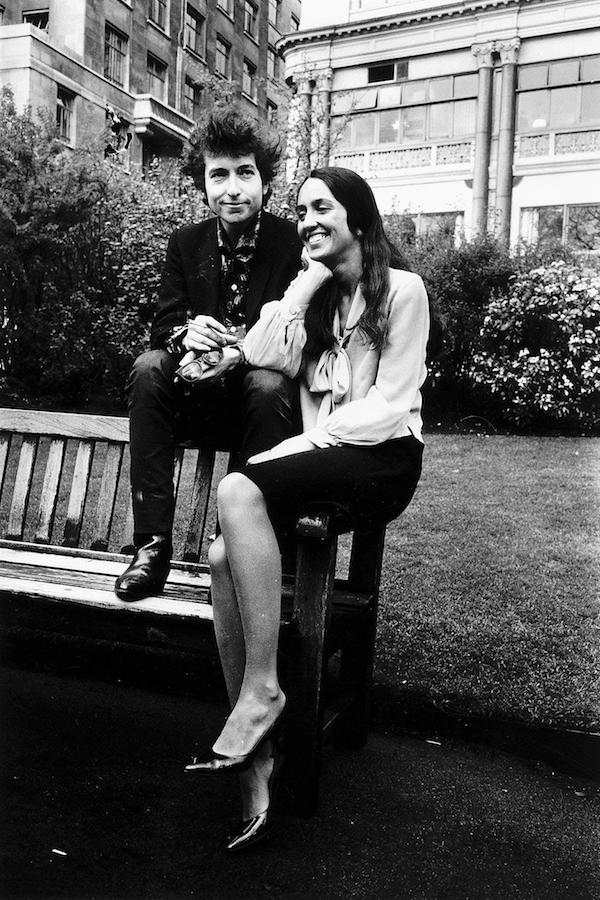

Bob Dylan gave no convincing reason. He hadn’t even responded to calls for a fortnight. So when he finally gave the Nobel Committee a firm ‘no’ to the question of whether he would be collecting one of the world’s most prestigious prizes, it caused something of an angry debate. On the one side, there were those who considered him the ungrateful adolescent; on the other, those who saw him as the rebel, going his own way, sticking it to the Man.

Saying no isn’t easy. We thrive on community cohesion. Having experienced it ourselves, we feel empathy with those to whom it is said; being said no to has been proven to cause genuine psychological damage. Small wonder then that saying no typically happens only privately, quietly, couched in obfuscation of the fact of the matter. The French get it. They refer to ‘je refuse’ - what strikes them as the right not to do something. It’s a right the French president Francois Hollande invoked in 2014 when asked point blank in an interview if he had had an affair, a question that would have been answered with prevarication by a politician of any other nation.

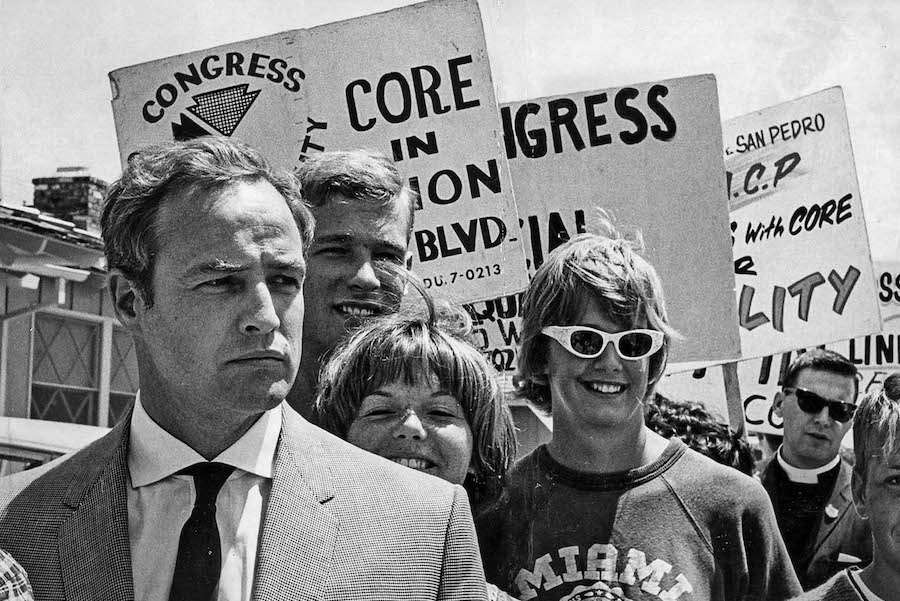

Perhaps this is because saying no is, ultimately, an expression of freedom, but also of power. “The difference between successful people and really successful people is that really successful people say no to almost everything,” as Warren Buffett, one of the world’s richest men, has it. “The art of leadership is saying no,” as Tony Blair, previous British prime minister and three time general election winner, had it. But this is not to say there is no cost to what can, on the surface, look to be merely linguistic rebellion. Some have seen putting their careers on the line as the acceptable price of outspokenness. Marlon Brando may be the best known of actors to have said no thanks to his Oscar win - In 1973 he sent a Native Indian representative in his stead and, to a chorus of boos from the audience, issued a statement about the misrepresentation of the United States’ indigenous peoples in the movies. Yet he was not the first.

Two years prior, George C. Scott shunned the Hollywood establishment - which has made countless millions out of stories of the lone rebel - not once but twice, first by rejecting his ‘Best Actor’ nomination for Patton, then by turning down the award when he won it anyway. The Oscars ceremony was, he said, in no uncertain terms, “a two hour meat parade, a public display with contrived suspense for economic reasons. The crying actor clutching the statue to his bosom - it’s all such a bloody bore.”

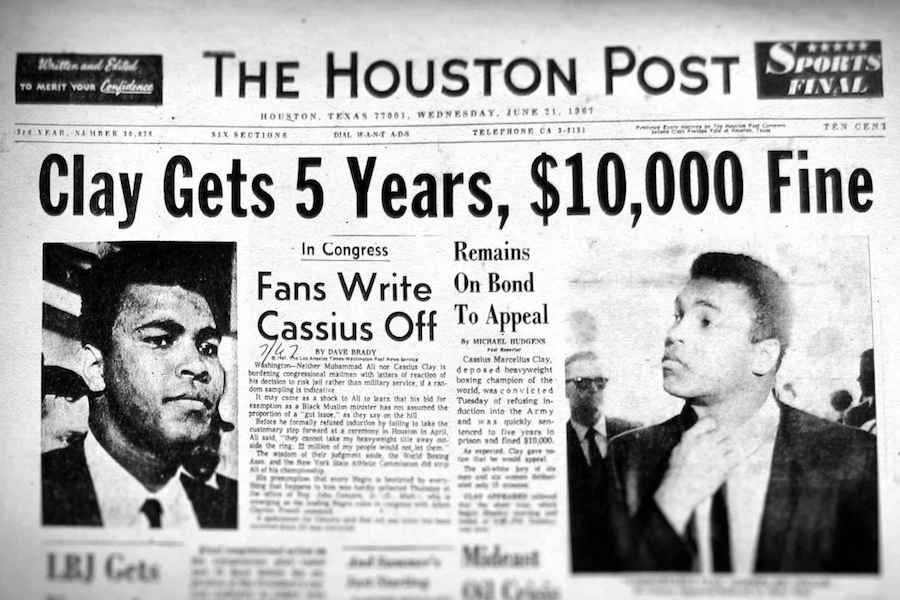

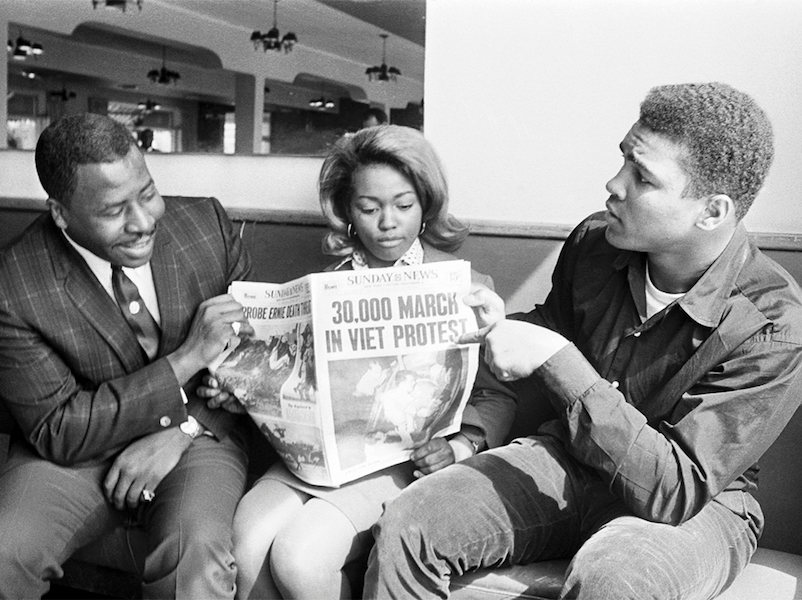

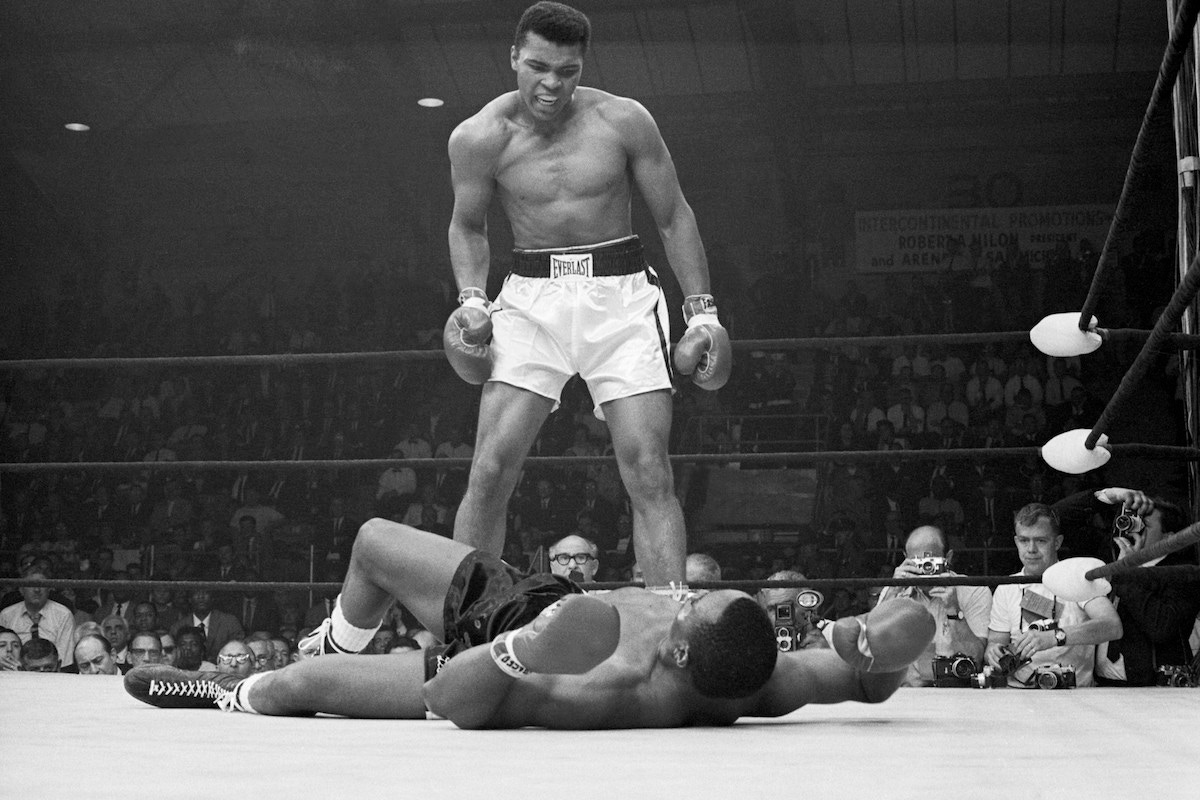

The cost rises too: a five year jail term, for example, albeit suspended. When, 50 years ago this year, the 25-year-old Cassius Clay (later Muhammad Ali) said he would not enter the US forces draft to serve in the Vietnam War, he was stripped of his championship title and suspended by boxing authorities, effectively giving up his best fighting years as a result. Again, the ‘no’ was castigated as the act of the ingrate. “The tragedy, to me, is [that] Cassius has made millions of dollars off of the American public, and now he’s not willing to show his appreciation,” as the baseball legend Jackie Robinson put it. Sports Illustrated was more brutal: “Without his gloves on, Ali is just another demagogue.”

And, while history has its long list of Galileos, known and anonymous - refusing to bend to authority’s version of events when conscience or the facts say otherwise - there are those who, more recently, have risked death with their refusal. Take, for instance, one August Landmesser. Unfortunate enough to be a German who fell in love with a Jewish woman in a country under Nazi dictatorship, and subsequently denied the right to marry, in 1936 he was photographed among a huge throng of people at an event where Hitler was christening a new navy ship. While all of those around him are making the ‘sieg heil’ salute - then mandatory for all German citizens as a demonstration of loyalty to the Führer - he stands there with his arms defiantly folded. He was sent to a concentration camp for this simple gesture.

It’s the kind of gesture, however, that at least answers the skepticism that greets most nos - such is our suspicion of them, and perhaps, at some innate level, our fear of them. Is that why we’re all too keen to dismiss them as self-serving, rather than principled, as some suggested of Dylan? We’ve been here before, after all.

“What did he prove [in declining the award]?”, The Mail asked of Jean-Paul Sartre, when he also declined his Nobel Prize, in 1964. “[It was] a rather ineffectual and stupid gesture. Sartre will not allow himself to be packaged, labeled or delivered before the world as winner of the Nobel Prize. People might understand him then. He has been labeled (God forbid) and it is only an act of pretension to deny that it has meaning and not have the humility to accept this fact.” With admiration, or admonishment? We must greet refuseniks with caution. But not so much that we fail, when they are really there, to see great heroics in such a little word.