GREAT DRUNKS OF OUR TIMES

Pythagoras called sobriety 'the strength of the soul'. He was also a vegetarian who believed the mysteries of the universe could be unravelled using maths, so The Rake suggests you spurn his prudish mewings and raise a glass to the 20th century's greatest grog-addled hellraisers.

'Aristotle, Aristotle was a bugger for the bottle, Hobbes was fond of his dram, And René Descartes was a drunken fart, I drink therefore I am.'Monty Python's Philosopher's Song - a ditty penned by Eric Idle, which alluded to the capacity of history's great thinkers to sup from the cup of Bacchus - was a moment of cerebral comedy genius. Not only was it packed with lyrical virtuoso (the line 'There's nothing Nietzsche couldn't teach ya 'bout the raisin' of the wrist' is a poetic peach), but it also managed to incorporate the schools of thought expounded by the savants it cheekily lampooned (Immanuel Kant being 'very rarely stable', for example, alludes to any inebriate's wobbling gait, but more subtly to the German ethicist's theory of a stable universe).

Given the Pythons' intellectual credentials, Idle's feat in injecting such academia into his daft-yet-deep masterpiece is no surprise. But the song is endowed with extra comic resonance for the fact that it is apposite, for there is an unequivocal correlation between intellect, competence and influence (most of the philosophers were the A-listers of their time) and a predilection for the bottled magic with which mankind has enjoyed a heady relationship ever since some serendipitous Neolithic first noticed the mind-bending effects of fermented berries.

If you're not content with the proof that can be found in ancient history - Alexander the Great built an empire stretching from Greece to India in just a decade while practising a deeply dipsomaniacal devotion to the cult of Dionysus, the God of wine - then what about modern science? In 2013, Finnish researchers gathered data on 3,000 fraternal and identical twins and found that the sibling who first developed verbal ability also tended to be the first to experiment with, and subsequently form a relationship with, alcohol.

And if you're still not convinced, what about the endless list of extraordinary coves who have made an indelible imprint on political or cultural history despite a yen for revelry touched on in their obituaries and eulogies with euphemistic insinuations such as 'larger than life', 'convivial' or 'cheery'? Sir Winston Churchill is, of course, one of the first to spring to mind, the former British Prime Minister having conducted an entire theatre of war while enjoying a little more than the odd glass of hock with breakfast. 'I must have a tumbler of sherry in my room before breakfast, a couple of glasses of scotch and soda before lunch, and Champagne and 90-year-old brandies before I go to sleep at night,' he once told a White House butler during one wartime visit.

His penchant for bubbly was cemented some years later, in 1945, at the British ambassador's home in Paris. There, a bottle of 1928 Pol Roger was served to toast the liberation of France; Churchill was so taken with it he bought all of the remaining 1928 and 1934 Pol Roger, and was sent a case at Chartwell, his home in Kent, every birthday onwards. When he died, in 1965, Pol Roger placed a black border around the labels of any bottles bound for England.

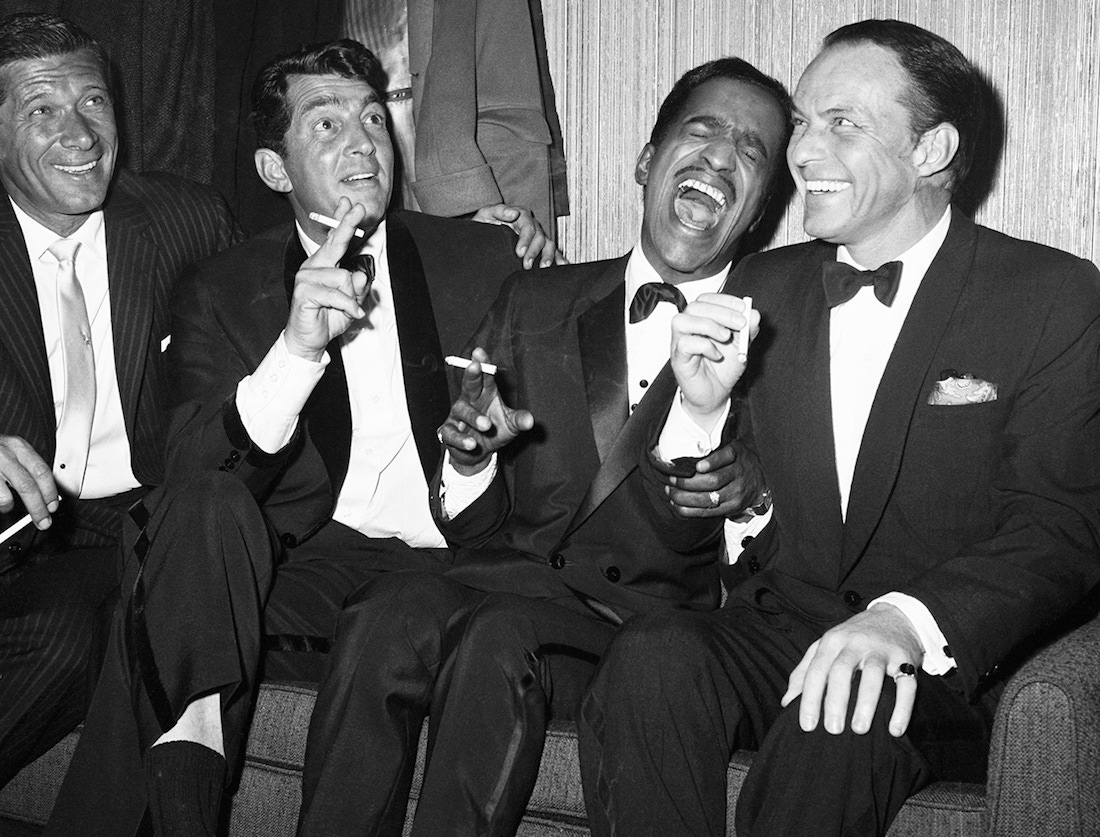

As he was a man disposed to grog-related quippery - ably demonstrated in his well-documented exchanges with Conservative MP Lady Astor* - Winnie must privately have been a great admirer of this witticism from Frank Sinatra: 'I feel sorry for people who don't drink - they wake up in the morning and that's the best they're going to feel all day.' In the crooner's case, though, the grog didn't always cheer his mood: in fact, it would seem those famous ol' blue eyes would more than occasionally mist over a garish red when he hit the bottle, particularly once he became depressed as his star waned in the mid-to-late sixties. For example, consider the occasion he ran up a $500,000 gambling debt at The Sands in Las Vegas, disappeared for a weekend, came back soused, drove a luggage cart through a glass doorway, tried (and failed) to set fire to the curtains, then arranged a hit on the manager for refusing him his usual $50,000 worth of free chips.

No amount of marital cajoling - Sinatra's first wife, Nancy Barbato, would lock him in the room if she saw the gin was out - was going to stop him doing it his way, so to speak, and he would go on to be buried with a flask filled with Jack Daniel's on his death in 1998, aged 82. 'Alcohol may be man's worst enemy, but the Bible says love your enemies,' was another of his witticisms (despite this mild sacrilege, Sinatra was a staunch Catholic, having turned to the church as a salve after his mother died in a plane crash). The juice certainly didn't do his career any harm: across six-plus decades of recording and performing, Sinatra sold 150 million records and won 11 Grammy awards.

While the insouciance that made Sinatra's friend Humphrey Bogart the greatest film actor of his time could have been linked to his expansive drinking ('Bogie had an alcoholic thermostat,' recalled another friend. 'He set his thermostat at noon, pumped in some scotch, and stayed at a nice even glow all day, re-dosing as necessary'), some sources, including his New York Times obituary, suggest that Dean Martin fostered a fictitious reputation as a Highball-quaffing inebriant in order to distinguish himself within the (unofficially) Sinatra- skippered Rat Pack. Martin had a ready stream of drink-related repartee - 'You're not drunk if you can lie on the floor without holding on,' he once said - but whether or not the man dubbed the Clown Prince was drinking anything stronger than apple juice on stage remains a matter for debate.

Around the time that the Rat Pack (with one possible exception) were honeying their vocal chords with hard liquor, a quartet of ultra-talented British actors - Richard Burton, Richard Harris, Peter O'Toole and Oliver Reed - were starting to make Sinatra et al's adventures look tame. None of those four men was the original silver-screen carouser; that accolade would go to Errol Flynn. A one-time drinking partner of Fidel Castro, the Tasmania-born action hero co-rented a Malibu orgy venue with pal David Niven that they nicknamed Cirrhosis-by-the-Sea. Like Sinatra, Flynn was buried with his one true love: in his case, six bottles of whisky.

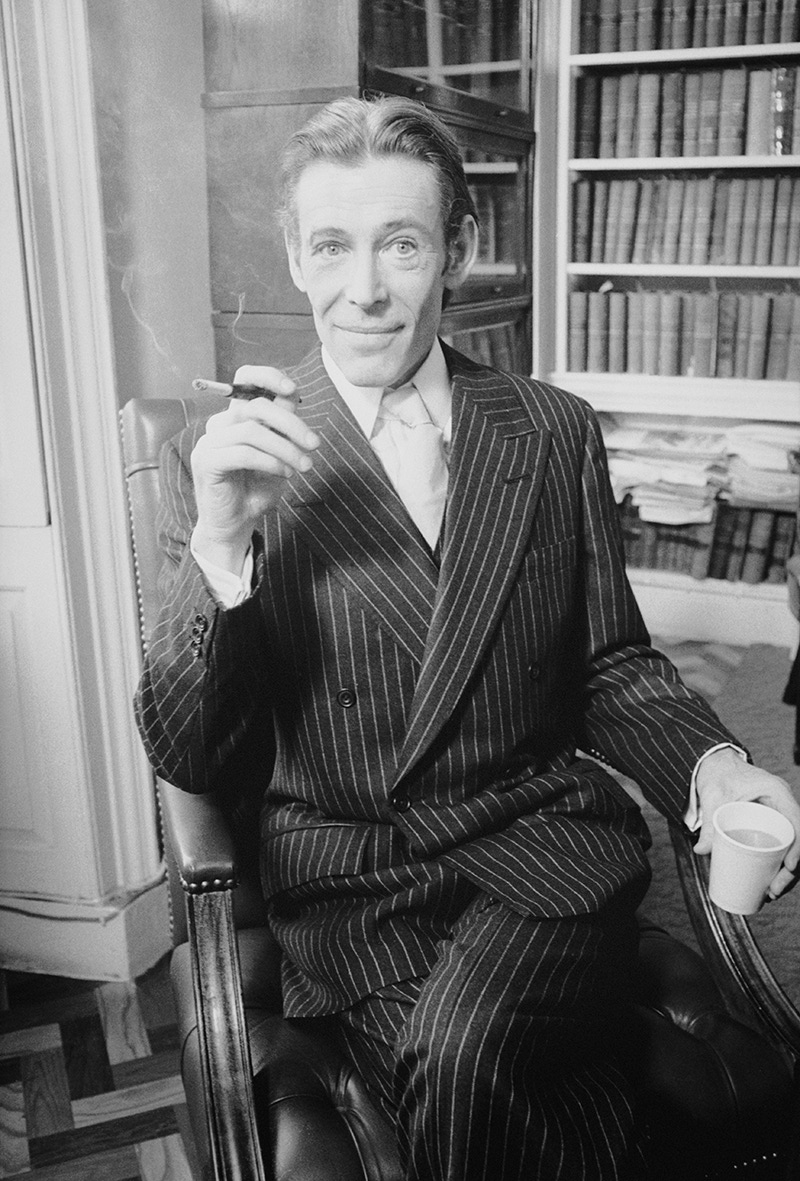

Yet the exploits of Burton, Harris, O'Toole and Reed were titanic. Burton - who, lest we forget, was the most formidable Shakespearean actor of his generation, dubbed 'the natural successor to Olivier' by critic Kenneth Tynan - would regularly hammer three bottles of vodka a day. Once, during the filming of 1964's The Night of the Iguana in Mexico, he dived into the sea in pursuit of an imaginary shark. A scene in The Spy Who Came in From the Cold, in which his character was required to down a glass of whisky, took a vast number of takes - 47, to be precise - with onlookers reasonably suspecting that he was fluffing his lines on purpose. Doctors operating on him three years before his death in 1984 discovered that his spinal column was coated with crystallised booze.

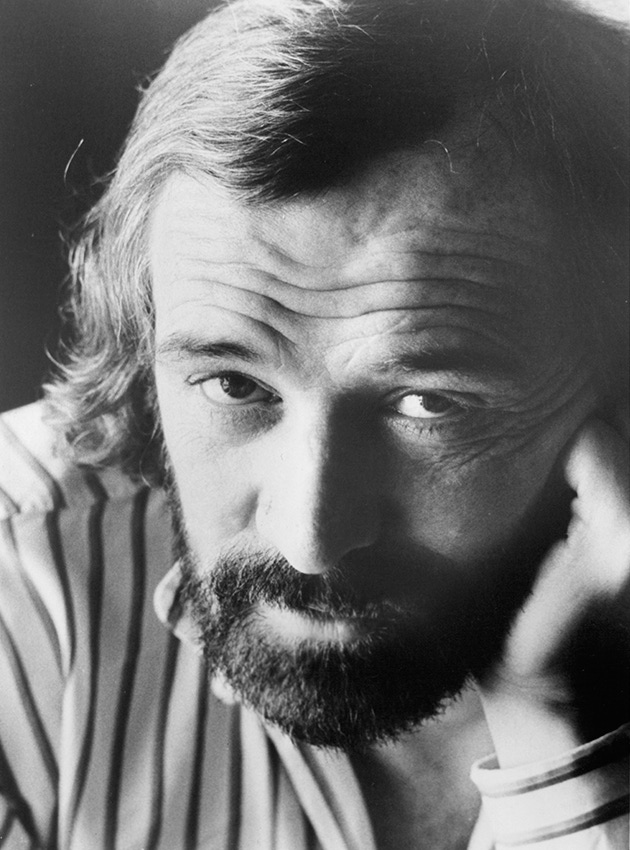

Burton's good friend, the Limerick-born Richard Harris - who racked up a film career including gems such as This Sporting Life, A Man Called Horse, The Wild Geese and Gladiator before dying of Hodgkin's disease aged 72 - had a habit of telling his wife he was off for a pint in the local pub only to wake up in a random foreign police jail days later. At his peak, he was necking two bottles of vodka a day plus a bottle each of port and brandy.

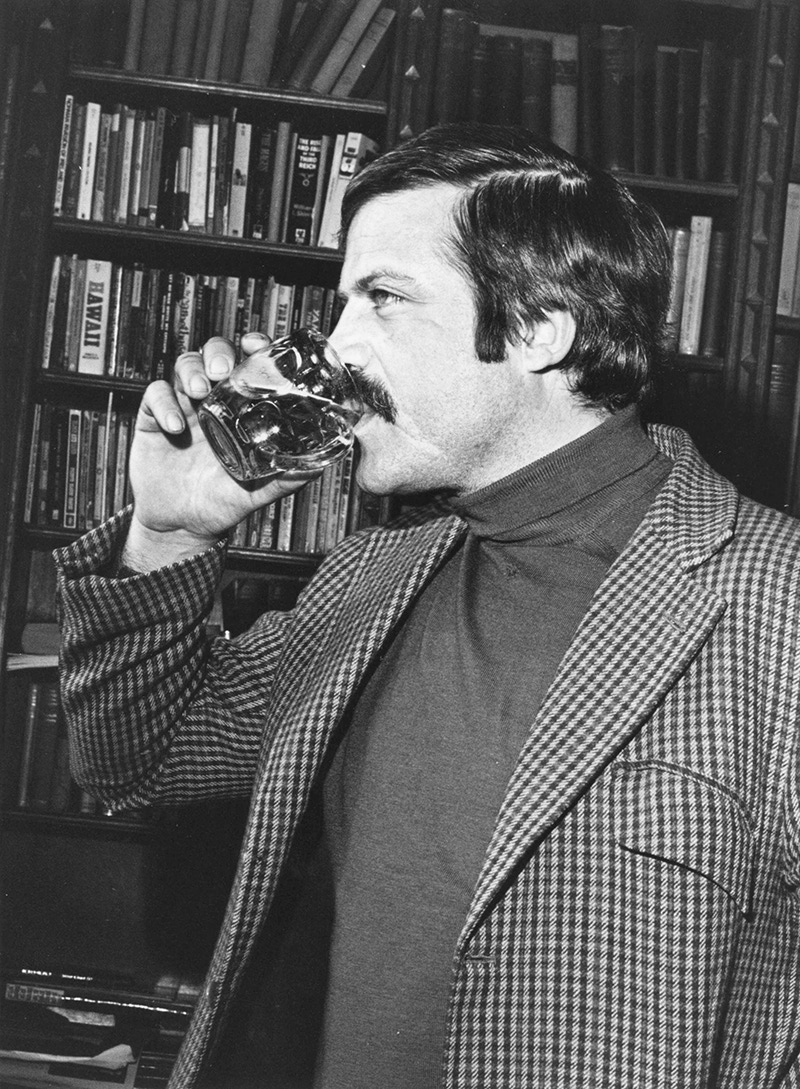

O'Toole was, relatively speaking, moderate with his intake of a single bottle of whisky a day, and of the quartet it was Reed whose alcoholic exploits commanded most attention. The Londoner, whose nuance and screen presence made him impossible not to watch in movies such as Sitting Target, Women in Love, Revolver and the little-known The Party's Over, once drank more than 100 pints of beer in less than 24 hours before successfully doing a horizontal handstand on the bar. In 1980, at the reception of a Christening at which he was Godfather, he started a game of rugby with the infant as the ball, pretending to toss the swaddled bundle to imaginary players. He downed 12 double rums and a number of whiskys following a day's filming on Gladiator, and very possibly exposed the tattooed penis he nicknamed his 'mighty mallet' before dying in his sleep aged 61.

But if there is one professional group that has proved most likely to seek inspiration from the bottle, it is those who live by the pen. Stalin described writers as 'the engineers of the soul', and they should also, arguably, be deemed philosophers as much as any of those mentioned in the Python song. The writer's passion for the punch is both timeless and ubiquitous. 'Once drunk, a cup of wine can bring 100 stanzas,' wrote the poet Xiuxi Yin in the third century AD. Eleventh-century Persian bard Omar Khayyám referred to wine as 'all that youth will give you'. The great Urdu poet Mirza Ghalib declared himself half Muslim on the grounds that he avoided pork but refused to resist great quantities of wine. 'Too much Champagne is just right,' slurred F. Scott Fitzgerald. 'Civilisation begins with distillation,' is how William Faulkner put it. The querulous French writer Baudelaire expressed his views on the subject with characteristic Gaelic dogmatism: 'Always be drunk.'

Ernest Hemingway, Truman Capote, Jack Kerouac, Charles Bukowski and Hunter S. Thompson, as well as a smattering of women writers - Jean Stafford, Patricia Highsmith, Elizabeth Bishop, Jane Bowles and Anne Sexton among them - were no slouches when a brimming glass was put in front of them. But again the British isles steal the plaudits for juggling the love of a gargle with literary excellence. It isn't surprising given how tightly woven alcoholism is in Britain's cultural fabric. The Celts were brewing ethanol long before the Romans arrived, while what we now call beer dates from the ninth century.

By the time Chaucer was serving up bawdy reading for school syllabuses 600 years into the future, there were almost 1,400 pubs serving London's population of around 80,000 - or one for every 57 people. At the peak of the early 18th- century gin craze, the year 1714, English distillers made two million gallons of the stuff. Three hundred years later, heavy taxation has done little to curb the nation's thirst, and Samuel Johnson's declaration that 'a tavern chair is the throne of human felicity' remains an axiom to which most of Blighty's population would assent with a slow, deliberate nod and a poorly suppressed hiccup.

But if there is one professional group that has proved most likely to seek inspiration from the bottle, it is those who live by the pen. Stalin described writers as 'the engineers of the soul', and they should also, arguably, be deemed philosophers as much as any of those mentioned in the Python song. The writer's passion for the punch is both timeless and ubiquitous. 'Once drunk, a cup of wine can bring 100 stanzas,' wrote the poet Xiuxi Yin in the third century AD. Eleventh-century Persian bard Omar Khayyám referred to wine as 'all that youth will give you'. The great Urdu poet Mirza Ghalib declared himself half Muslim on the grounds that he avoided pork but refused to resist great quantities of wine. 'Too much Champagne is just right,' slurred F. Scott Fitzgerald. 'Civilisation begins with distillation,' is how William Faulkner put it. The querulous French writer Baudelaire expressed his views on the subject with characteristic Gaelic dogmatism: 'Always be drunk.'

Ernest Hemingway, Truman Capote, Jack Kerouac, Charles Bukowski and Hunter S. Thompson, as well as a smattering of women writers - Jean Stafford, Patricia Highsmith, Elizabeth Bishop, Jane Bowles and Anne Sexton among them - were no slouches when a brimming glass was put in front of them. But again the British isles steal the plaudits for juggling the love of a gargle with literary excellence. It isn't surprising given how tightly woven alcoholism is in Britain's cultural fabric. The Celts were brewing ethanol long before the Romans arrived, while what we now call beer dates from the ninth century.

By the time Chaucer was serving up bawdy reading for school syllabuses 600 years into the future, there were almost 1,400 pubs serving London's population of around 80,000 - or one for every 57 people. At the peak of the early 18th- century gin craze, the year 1714, English distillers made two million gallons of the stuff. Three hundred years later, heavy taxation has done little to curb the nation's thirst, and Samuel Johnson's declaration that 'a tavern chair is the throne of human felicity' remains an axiom to which most of Blighty's population would assent with a slow, deliberate nod and a poorly suppressed hiccup.

So it figures that British writers' relationship with the sauce is one of unconditional adoration. Chaucer himself coined the phrase 'dronke is as a mous', a simile that has been handed down through the centuries, with the rodent replaced by 'wheelbarrow', 'whistle', 'aardvark' and 'lord' before the contemporary 'skunk' became popular.

Caitlin Thomas, the wife of Welsh poet Dylan Thomas - whose works, including the tellingly titled Do not go gentle into that good night, made him one of the most influential writers of the mid-20th century - wrote in her 1997 autobiography, My Life with Dylan Thomas: Double Drink Story, 'the bar was our altar'. The aura of bookish diffidence Philip Larkin gave off during his lifetime evaporated like a methylated flambé after his death, with Martin Amis describing him as 'a fuddled Scrooge and bigot, his singlet-clad form barely visible through a mephitis of alcohol, anality, and spank magazines'.

Of course, the lives evoked here were not without blight inflicted by the bottle, and the premature deaths of a good deal of the world's great talents and towering characters, particularly those who turned 'rock 'n' roll' into an adjective - Keith Moon, Janis Joplin, John Bonham and Amy Winehouse among them - are impossible to ignore. It's also difficult to argue with the notion that a predilection for booze is usually a collateral to human excellence rather than the source of it.

But considering the substance is associated with diminishing human competence, it's astonishing how many of life's biggest drinkers were or are prodigious in their fields. And, with a respectful nod and sympathy for those affected adversely by it, we cannot but raise a glass to the liquid organic compound that has become an integral part of the human story.

* For readers unaware of these exchanges, the most famous came when the prim politician accused the PM of being 'disgustingly drunk'. 'I may be drunk, Miss,' Churchill replied, 'but in the morning I will be sober and you will still be ugly.' On another occasion, Astor told Churchill that were he her husband, she'd poison his tea. 'Nancy,' he said, 'if I were your husband, I'd drink it.'