A Viennese Affair: Romy Schneider

One of French cinema’s most incandescent stars was Austrian-born actress Romy Schneider, whose short but prolific career — with more than 60 films to her name — belied the personal heartbreaks and tragedies that marked her life.

There is nothing like a premature death to gild one’s reputation. Just ask Joplin, Dean, Hendrix and Monroe. Or don’t. You may be waiting a while for an answer.

On 29 May 1982, vaunted actress Romy Schneider sat down at the desk in her Paris apartment to write a letter to a women’s magazine cancelling an interview. It would never be completed. She was 43. The official cause of death was listed as cardiac arrest, but others saw it as a grimly appropriate epilogue to a life marinated in that much booze, pills, tragedy and celluloid that it has, to date, prompted three biopics.

Born Rosemarie Magdalena Albach-Retty — a rather wordy name for a marquee — in Vienna, Austria, in 1938, Romy grew up in a family of actors. By the age of 15, standing barely a metre and a half in stockings, she had already fomented the knowing kitten-meets-Cupid allure, which would tear at men’s hearts and loins for the next 30 years.

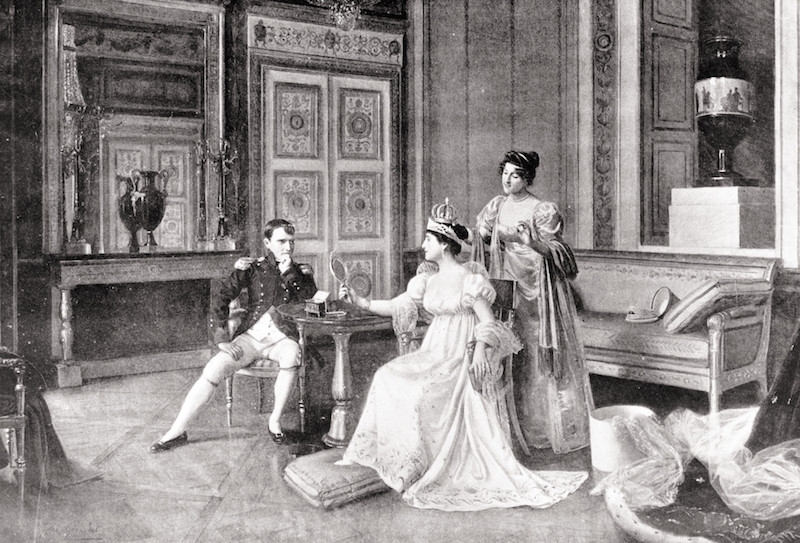

She first came to the attention of the European film-going public in the treacly trilogy Sissi, which began in 1955 and chronicled the romantic adventures of Elizabeth of Austria, who catches the eye of her sister’s fiancé, Emperor Franz Josef.

"By the age of 15, standing barely a metre and a half in stockings, she had already fomented the knowing kitten-meets-Cupid allure, which would tear at men’s hearts and loins for the next 30 years."It was a role that she would later say “sticks to me like oatmeal”. At the same time, the young woman was being stiflingly stage-managed by her mother Magda — “Mom stands behind one and whispers, ‘Smile now, smile…’” she would subsequently reveal — while her stepfather Hans Herbert Blatzheim had less-than-wholesome intentions. “He clearly asked me to sleep with him.” In 1958, she made her first foreign production Christine and promptly fell in love with co-star Alain Delon. Absconding from her predatory and stifling family, Schneider reinvented herself in Paris. She wrote, “I want to be completely French in the way I live, love, sleep and dress.” There were three people she later credited for her transformation from “healthy little dumpling” to smouldering ingénue: Delon, Coco Chanel and director Luchino Visconti. After a period where she said she was known as “the cheerful companion of the up-and-coming superstar Alain Delon”, she was eventually cast by Visconti in the 1962 film Boccaccio ’70. The director hailed her one of the most brilliant actresses in Europe, and a year later, Orson Welles cast her as Leni in his film version of Kafka’s The Trial. By 1965, she was established as a thespian of note, but her career success was soon to be fractured by a private pain in a dynamic that would play out repeatedly until the credits rolled on her life. Her marriage to Delon ended with a terse note reading “gone to Mexico with Natalie”. She responded by attempting to slash her wrists. A year later, she married director Harry Meyen, who had been tortured by the Gestapo during World War II and later hung himself. To say that Schneider was unlucky in love is a gross understatement.

Hollywood inevitably beckoned and she is probably best remembered for her minxy portrayal of Carole in the 1965 sex romp What’s New Pussycat? opposite Peter Sellers and Peter O’Toole. It’s safe to say that it was nobody’s best work.

Despite never having had an acting lesson, Schneider returned to Europe and built a career that would eventually span 61 films and net her two César awards (in 1976 and 1979 for L’important c’est d’aimer and Une histoire simple).

The work was Schneider’s balm and her succour, her meditation and her medication. Yet the three-packs-of-Marlboros-a-day pro-choice advocate reportedly gave as good as she got on set. “I have worked with the biggest tyrants: [Otto] Preminger, [Orson] Welles and [Luchino] Visconti. Despots — they have contempt for most actors. When they meet someone who stands up to them, everything’s great.”

But there are some things that simply cannot be vanquished. On 5 July 1981, her son David-Christopher was impaled on a fence outside her Paris home and died as a result of his injuries. And so began a spiral into alcoholism, depression and prescription-drug abuse. Although the marriage to her private secretary Daniel Biasini produced a daughter, Sarah Magdalena, it too ended in divorce.

"It’s her collected performances that have cemented her name as its own shorthand for success."In 1981, she was asked about the Sissi trilogy and replied, “I’ve not been Sissi for a long time now. I am an unhappy 42-year-old woman and my name is Romy Schneider.” Tragedy aside, where many of Schneider’s pulchritudinous contemporaries might be remembered for the way they rocked a bikini, inspired a million turgid fantasies or morphed into fashion icons, it’s her collected performances that have cemented her name as its own shorthand for success. An entire Austrian awards ceremony — The Romy — celebrates that nation’s best television, while the Prix Romy Schneider was created to laud French cinema’s most promising young actresses. One wonders what she’d have made of her legend, had she survived to witness the longevity that eluded her. For in this era of Mileys and Minajs, where the substance seems to come second to the style, Schneider was stacked on both counts. There was an impishness that, despite all the Burgundy, uppers and funerals, refused to be dulled. Perhaps the last word is best left to Alain Delon, the man who first captured then broke her fragile, flinty, tobacco-stained heart. At the grave which she shares with her son in Boissy-sans-Avoir cemetery, he placed a wreath that read: “You have never been so beautiful.” Of course, he said it in French — probably the only language that could do Schneider justice.