Bunker Spreckels: Riding the Wave of Sex, Drugs, and Sugar

Never has “live fast, die young” been taken more literally than in the case of Bunker Spreckels, the hedonistic, multi-millionaire surfing step-son of Hollywood legend Clark Gable. The Rake traces the incandescent trajectory of one of the 70s fastest burning stars

As far as history’s hellraisers go, Adolph Bernard Spreckels III is not a name that springs to the lips of many people. Keith Richards, yes. Jim Morrison, almost certainly. Oliver Reed, without a doubt. But Adolph B. Spreckels III? Born in 1949, and affectionately known as ‘Bunker’, his was a story of decadence orated through a megaphone dialled to full volume. The great-grandson of the German-born sugar baron, railway tycoon and publisher, Adolph Claus Spreckels, Bunker’s childhood was one punctuated by family feuds and Hollywood glamour, while his adulthood, fleeting as it was, played out in a palimpsest of drugs, sex, surfing, and martial arts. Bunker’s life was Exhibit A in the crime against conservatism, part cautionary tale about the dangers of flagrant excess, but also part inspiration to relentlessly pursue emancipation from mundanity.

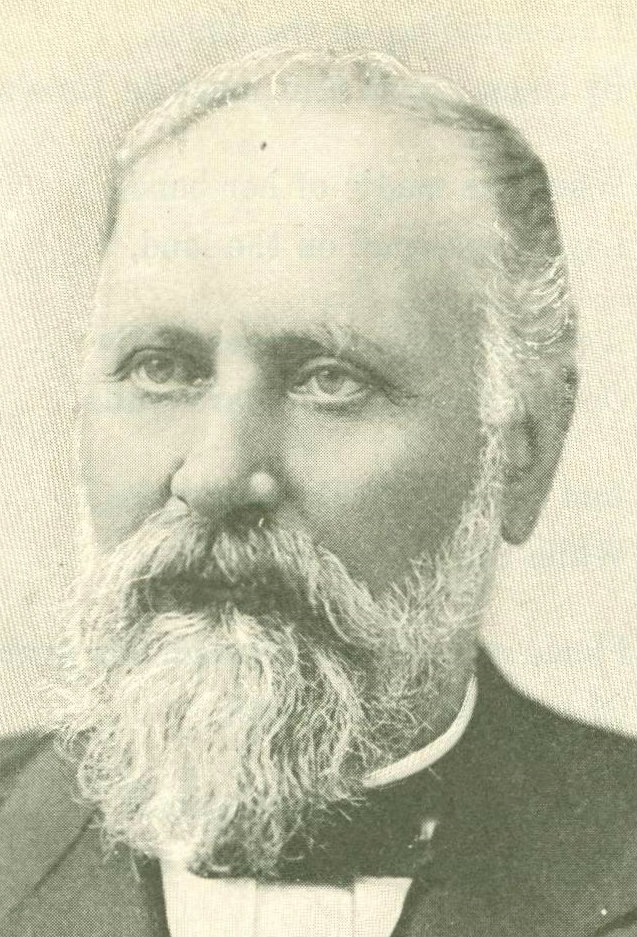

The story of Bunker really starts with his Claus, his great-grandfather, who in 1846 bid farewell to his home in Hanover, Germany and moved to the United States, carrying, reputedly, just one German thaler in his pocket (‘thaler’ is where the name ‘dollar’ originates). He married his childhood sweetheart in New York shortly after arriving (she had moved there three years previous) and, given there was little else to do in those days, had thirteen children, only five of whom were fortunate enough to make it into adulthood. The family moved to South Carolina to open a grocery business before upping sticks back to New York and then finally to South California, where the ever industrious and entrepreneurial Spreckels started a brewery. While reasonably successful, it wasn’t until the mid-1860s, when Spreckels got into the sugar refining business, that he quickly became extremely wealthy, able to corner the Hawaiian sugar refining trade. Railroad investment followed, and with a slew of clever investments in beet plantations, Spreckels was able to make a killing.

His standing was such in Hawaii that in 1878 Spreckels founded Spreckelsville, a company town along the northern shore of Maui, the home of Peahi, also known as ‘Jaws’, one of the world’s most fearsome big waves. By the end of the 19th century, Spreckelsville had grown into the largest sugarcane plantation in the world. In turn, Spreckels would become de facto money lender to King Kalākaua, in return for favourable land deals and water rights. From the man with one thaler in his pocket to one of the wealthiest men on the planet, Spreckels was the consummate immigrant success story and the poster boy for a generation of Americans for whom business opportunities and hard graft would be viewed as birthrights. When Claus died in 1908, the business was passed onto his second son, Adolph II, and from that moment on the family descends into a litigation mess that makes Dynasty look like Little House on the Prairie. The siblings, all of whom were already millionaires, sued and countersued one another for a bigger slice of their father’s pie.

In 1884, furious after the Spreckels Sugar Company was accused of defrauding its shareholders by the San Francisco Chronicle, Adolph II tracked down the newspaper’s co-founder Michael H. de Young and shot him. Spreckels pleaded temporary insanity to the charge of attempted murder and was acquitted, which is perhaps no surprise given the wealth and standing of the man, not to mention the levels of investment the Spreckels family had poured into California over the years. Adolph Bernard II was also the genesis of the term ‘sugar daddy’, a moniker given to him by his wife Alma de Bretteville, a woman 24 years his junior (Alma also had a number of monikers bequeathed to her, notably “Big Alma” on account of her 6” 1’ frame, and “The Great Grandmother of California”, for being a generous patron of the state). Between them, they had a son whom they named Adolph Spreckels Jr (still with us?) who in turn married a former model by the name of Kathleen Williams.

And so we get to Bunker, their son. When Kathleen’s marriage collapsed to Adolph Jr, she fell into the arms of one Clark Gable, who took Bunker on as his own, schooling him in the arts of hunting and Hollywood artifice (In one of Bunker’s final interviews, with writer CR Stecyk III, he said of Gable: “I'll say one thing - he was the same way at home that he was on the screen. He didn't change very much. He was from that no-crap school of acting and that's the way he lived, too. He was never one to talk about himself… He taught me how to shoot. He taught me how to use different weapons - knives and bullwhips, that type of thing. He was good with a whip. He was good with a lasso, good in the cowboy arts. Good with horses. He was good with animals. He was into hunting and fishing.”) Gable was, by many accounts, a wonderful stepfather to Bunker, but when he died suddenly in 1960, he left in his wake a boy with a wild streak who had never lived by the de facto rules of society, and an heir to a ridiculously large inheritance. In the years after Gable died, Bunker is said to have used the actor’s Oscar trophy as a doorstop. What could possibly go wrong?

Between the ages of 15 and 20, Bunker made ends meet by selling bags of weed here and there while living on Gable’s ranch. His girlfriend at the time was Miss Teen California and they would kill time cruising around in her trophy car. Despite embarking on a promising career as a stockbroker, Bunker returned to his family’s de facto homeland of Hawaii when was 18 (he wouldn’t inherit his fortune until 21) and threw himself into surfing culture (he’d originally envisioned himself flying missions into Vietnam). As a young boy, he had already been taken on by the island’s nobility. Because of his family’s support of the king, David Kalākaua, many of the old kahunas believed Bunker to be a reincarnated Hawaiian prince and taught him from an early age the ways of Pacific island life. Hunting, arching, fishing, and of course surfing, his true passion.

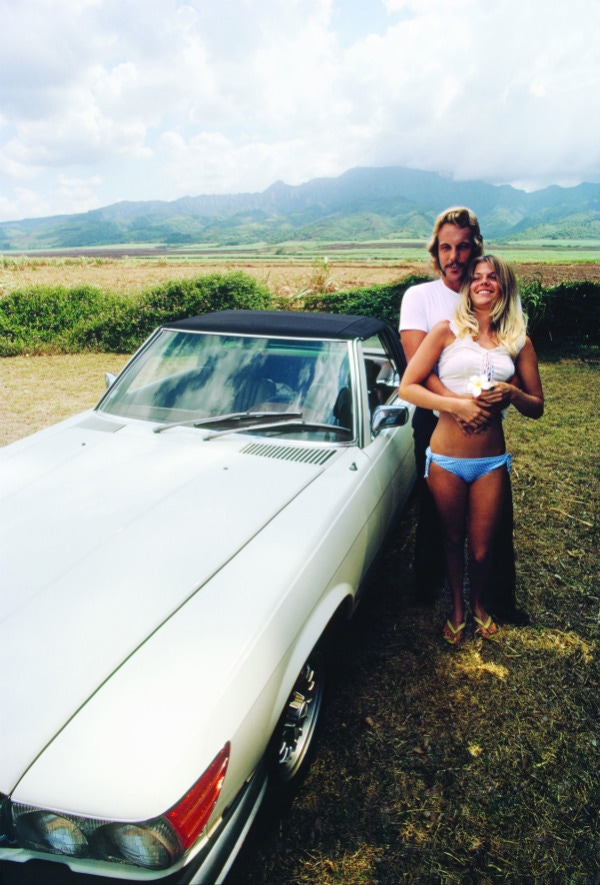

Depositing himself with the hardcore surfing crowd on Oahu’s North Shore, home of the fabled Banzai pipeline, Bunker lived a feral hand-to-mouth existence, waking early, surfing all day, and partying all night. He made scraps of money by shaping surfboards for friends and actually pioneered a type of board rail that would forever change the course of short-board surfing. Surfing magazines soon got wind of this blond, statuesque, soon-to-be multi-millionaire surfing maverick and began to follow his every move. When he eventually turned 21, his bank account improved to the tune of $50 million. And then all hell broke loose.

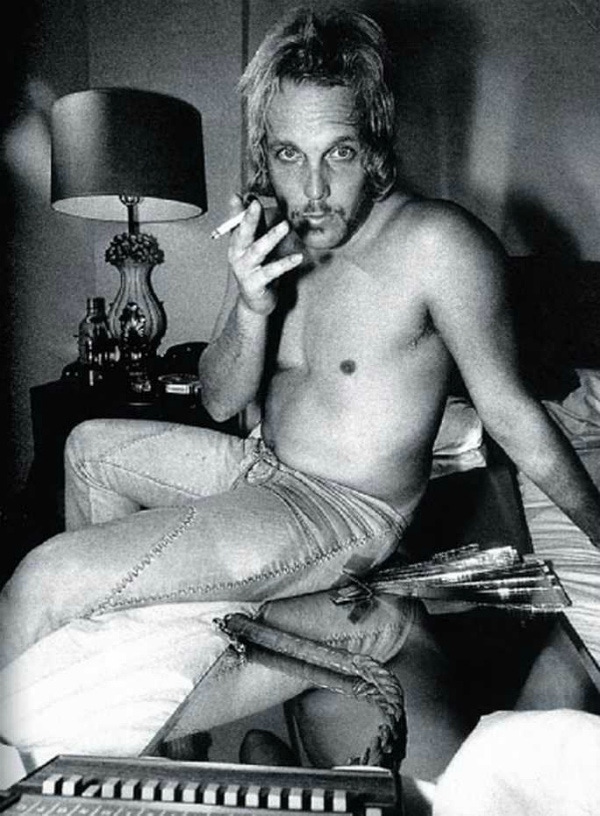

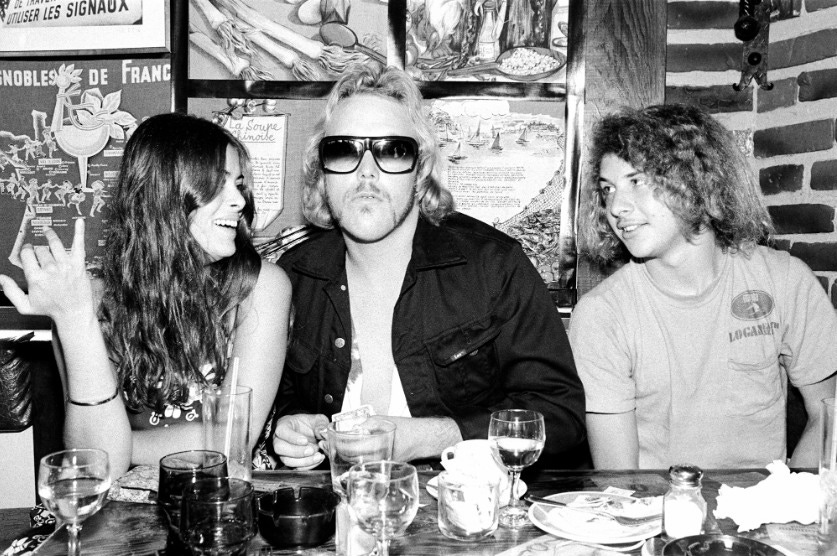

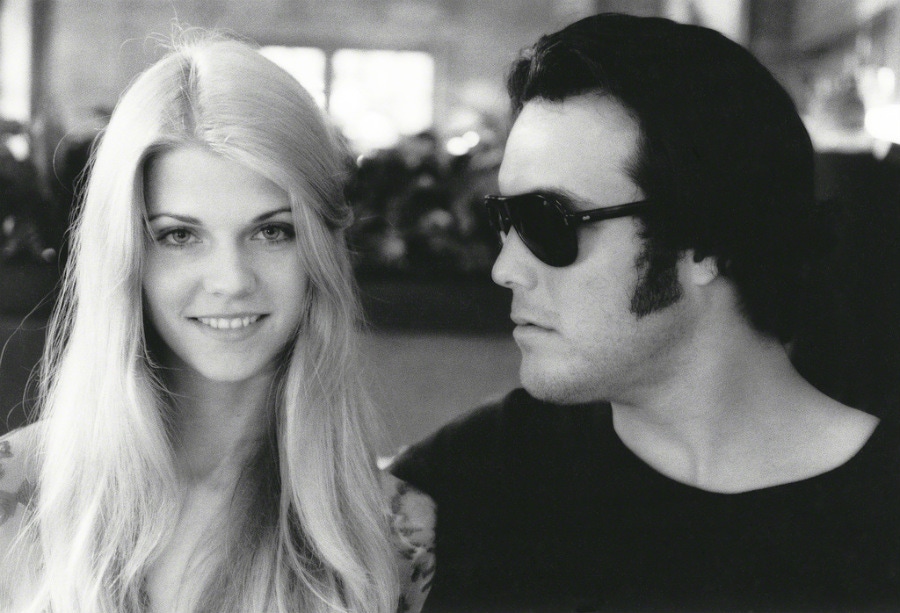

The ascetic surfing life was very quickly replaced with a manic, peripatetic existence, with Spreckels creating global bases at the Hotel George V in Paris, the Hotel Edward in South Africa, the Yacht Harbor Towers in Honolulu, the Kuilima Estates in Kahuku and Sunset Tower in Hollywood. After being badly beaten up in a street fight in Hawaii, Bunker approached a local martial arts guru called Professor Chow and studied under him for two years. In short, he became an acid-dropping, heavy-drinking, surf-mad, gun-toting hedonist, who could also handle himself. It was during these years that he met the young surf photographer Art Brewer and the two struck up a mutually beneficial, if not fraught, relationship. Bunker required an audience to play up to while Brewer had found the ultimate medium to take his photography to the next level. And so began the documentation of Bunker’s extraordinary life. He was the perfect subject: tall, striking, muscular with a shock of blond hair. He was also a flamboyant dresser: if he wasn't in board shorts, he was invariably layered in furs, flairs and leather pants. Wherever he went he caused a stir, but with Brewer's shutter constantly aimed at him, he developed a new level of showmanship that would often land them in trouble.

Aside from Brewer’s incredible photographs (compiled in Taschen’s Bunker Spreckels: Surfing’s Divine Prince of Decadence), it’s Spreckels’ final interview with the American subculture writer CR Stecyk III which is probably most revealing about the final years of his life. There is a tangible matter-of-factness in his answers, such as when he is asked what he spent his money on: “Cars, yachts, women, wives, travelling, having a good time, partying, houses, gambling. The usual material things.” Or his record for women (perhaps apocryphal) in those heady days: “I used to fuck a lot. Still do. My record? Let's see. I nailed 64 chicks in one week. That was pretty interesting.” But it’s Spreckels’ recounting of his drug use which is most poignant, given he was found dead at the age of 27 from an overdose of morphine:

“Drugs and surfing sort of go hand in hand, in the sense that it's the kind of lifestyle with which drugs are more or less an occupational hazard, like in the world of rock music… I believe it [LSD] was a factor in rearranging the boards. The boards got smaller. The surfing got more radical. People were having hallucinations and visions and vibrations, spiritual revelations. Or else they were having complete bummers. Surfing just seemed to be the only thing to do when you take a dose of acid. It was a hell of a lot better than sitting around in somebody's room staring at them, thinking you were reading their mind or having some kind of hallucinogenic tangent. I think that the only drugs that really brought surfing through to another level were the psychedelic type - mushrooms, mescaline, psilocybin. Other drugs are like anaesthesia. They make you so numb that they shut your senses down so you can't feel the currents that are going on around you. They make you numb.”

At his peak, Spreckels was dropping acid every day: “I'd mix psilocybin with mescaline and LSD and smash it up, and then chop it up into a powder and keep it in a bottle. When I'd wake up in the morning I'd take a little snort. Just one snort in the morning and that would be it for the rest of the day.”

Just one snort. For many of us, a double espresso in the morning is enough to facilitate carnage for the next few hours. Ultimately though, Spreckels’ would tragically underestimate the pull of dropping out of reality: “I've always been able to control it. I've always been able to get up and walk away from drugs whenever I wanted to. Because I have a lot of willpower. I only take drugs when I want to or feel like it.” The only trouble was, Spreckels felt like it every minute of his existence and eventually, like so many others, it would catch up to him and prove that his estimation of his own willpower was at best delusional. As Ralph Waldo Emerson once wrote, “Money often costs too much.” In Bunker Spreckels’ case, it cost him everything.