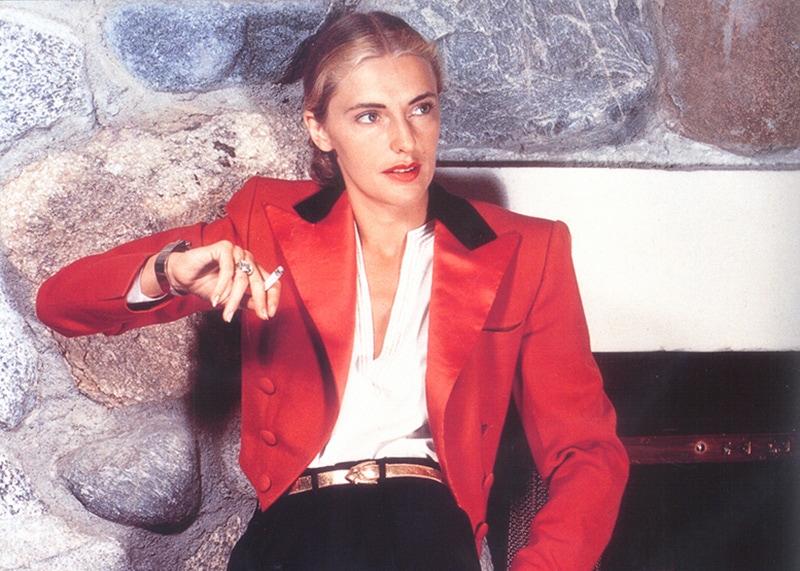

Tuesday Weld

Tuesday Weld never wanted to be a huge star, which is just as well, for her choice of movie roles was ‘self-destructive’, and off-screen she made Lindsay Lohan and Paris Hilton look like sorority girls collecting abstinence pledges. Instead, Tuesday became a cult figure in Hollywood, and she has retained that strange allure into her cloistered retirement.

Benedict Cumberbatch wouldn’t have lasted a moment. Back in the day, actors and the power-players at Hollywood studios would change names quicker than you could say Maurice Micklewhite. (Maurice is better known as Michael Caine.) Issur Demsky became Kirk Douglas; Joan Crawford spent her formative years as Lucille LeSueur; and little Audrey Hepburn was christened Edda Kathleen van Heemstra Hepburn-Ruston.

Tuesday Weld was one such nominative confection. She was born Susan Ker Weld in New York in 1943, but because of the pronunciation trials of a young cousin (who called her ‘Tu- Tu’), she eventually became known by the second working day of the week. Her father, Lathrop Motley Weld — strange names seem to be hereditary in this clan — died when she was four. A preternaturally beautiful child, Tuesday was put to work as a model by her mother, Yosene (yes, Yosene), to make ends meet.

And meet they did, thanks to a parent who was part showbiz mom cliché and cautionary tale. Tuesday later said: “I became the supporter of the family, and I had to take my father’s place in many, many ways. I was expected to make up for everything that had ever gone wrong in Mama’s life. She became obsessed with me, pouring out her pent-up love — her alleged love — on me, and it’s been heavy on my shoulders ever since. Mama still thinks I owe everything to her.”

Still-life gave way to motion pictures and Los Angeles. In 1956 she made both her television debut and first film appearance, in Alfred Hitchcock’s The Wrong Man. She was 12 years old and had already had a nervous breakdown, was battling alcoholism, and had tried to take her own life. Your standard Hollywood trifecta.

Her career gathered momentum with a role in the 1956 film Rock, Rock, Rock, and she was introduced to the television viewing public en masse in 1959’s The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis. She was girl-next-door cute with just enough woman- your-mother-warned-you-about. The eyes that flickered above those astral cheekbones suggested that with a bottle of hooch, a secluded parking spot and a warm summer night, this was a girl who might well go all the way.

Such perceptions were only heightened by her off-screen behaviour. In short, she made Lindsay Lohan and Paris Hilton look like prim sorority girls door-knocking for abstinence pledges. She was the true north of tabloid magnets, as you might be when (as a not-yet-legal teen) you sprout sentences like, “The man I marry will have to be richer than I am”. Yosene didn’t help matters. Asked if her daughter was allowed out after 11pm, she roared: “Ha, ha. That’s when she starts out.”

There were rumours of dalliances with men three times her age, and she drip-fed the press with hints of addiction, sexual activity and family discord. This was, after all, a 16-year-old who marched into the lobby of the Beverly Wilshire Hotel and demanded to be allowed into Elvis Presley’s room. She succeeded. Things took a turn for the curious when it came to Weld’s career. Consider the movies she turned down: True Grit and Lolita, to name just two. She was also in the running for Rosemary’s Baby. Instead, she opted for B-fare that verged on Grindhouse, like 1968’s Pretty Poison. Such was her wild persona by 1971 that when her performance in A Safe Place was criticised by a punter at the New York Film Festival, she lobbed one of her heels at him. Who throws a shoe? Honestly.

A year later there was talk of her being nominated for an Academy Award for the lead role in the adaptation of Joan Didion’s Play It As It Lays. She would finally be nominated for her turn as Diane Keaton’s awry sister in Looking For Mr. Goodbar, but by then she seemed over Tinseltown and its attendant mirages. We are, after all, dealing with a woman who in 1971 told Roman Polanski he could shove his nude sleepwalking scene for Macbeth up his own lens. She would muster a similar level of enthusiasm for screen-testing for the role of Daisy Buchanan in the 1974 production of The Great Gatsby. “I do not ever want to be a huge star,” she said. “I refused Bonnie and Clyde because I was nursing at the time but also because, deep down, I knew that it was going to be a huge success. The same was true of Bob and Carol and Fred and Sue, or whatever it was called (she was referring to the 1969 hit Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice). It reeked of success.”

Despite this outward rejection of standard operating procedure, she managed to stick to the La-La script with three marriages: to screenwriter Claude Harz, musician Pinchas Zukerman, and how- the-fuck-was-he-a-sex-symbol Dudley Moore. Still, for the actress who seemed, according to one scribe, to be “sweet little 16 for 16 years”, there was some verdigris of reward in the work. There were rare appearances, such as the 1984 Mafia series Once Upon a Time in America and 1993’s Falling Down, opposite Robert Duvall and Michael Douglas.

Despite her self-imposed absence from the spotlight, Weld has maintained an appropriately niche allure in the pop culture psyche. She featured on the cover of Matthew Sweet’s 1999 album, Girlfriend; there is a British band called The Real Tuesday Weld; and she is name-checked by Steely Dan’s Donald Fagen in the song New Frontier. She is under no illusion about the charmingly tarnished place she holds in many a contemporary heart. “I may be self- destructive,butIliketakingchanceswithmovies,”shesaid.“Ilike challenges, and I also like the particular position I’ve been in all these years, with people wanting to save me from the awful films I’ve been in ... I think the Tuesday Weld cult is a very nice thing.”

Even as she aged and made a life in the mountains of Colorado, she retained a coltish allure offset by the snappiest of tongues. Asked by a reporter what drove her to isolation in the 1970s, she responded: “I think it was a Buick.”