LIKE FATHER, LIKE DAUGHTER

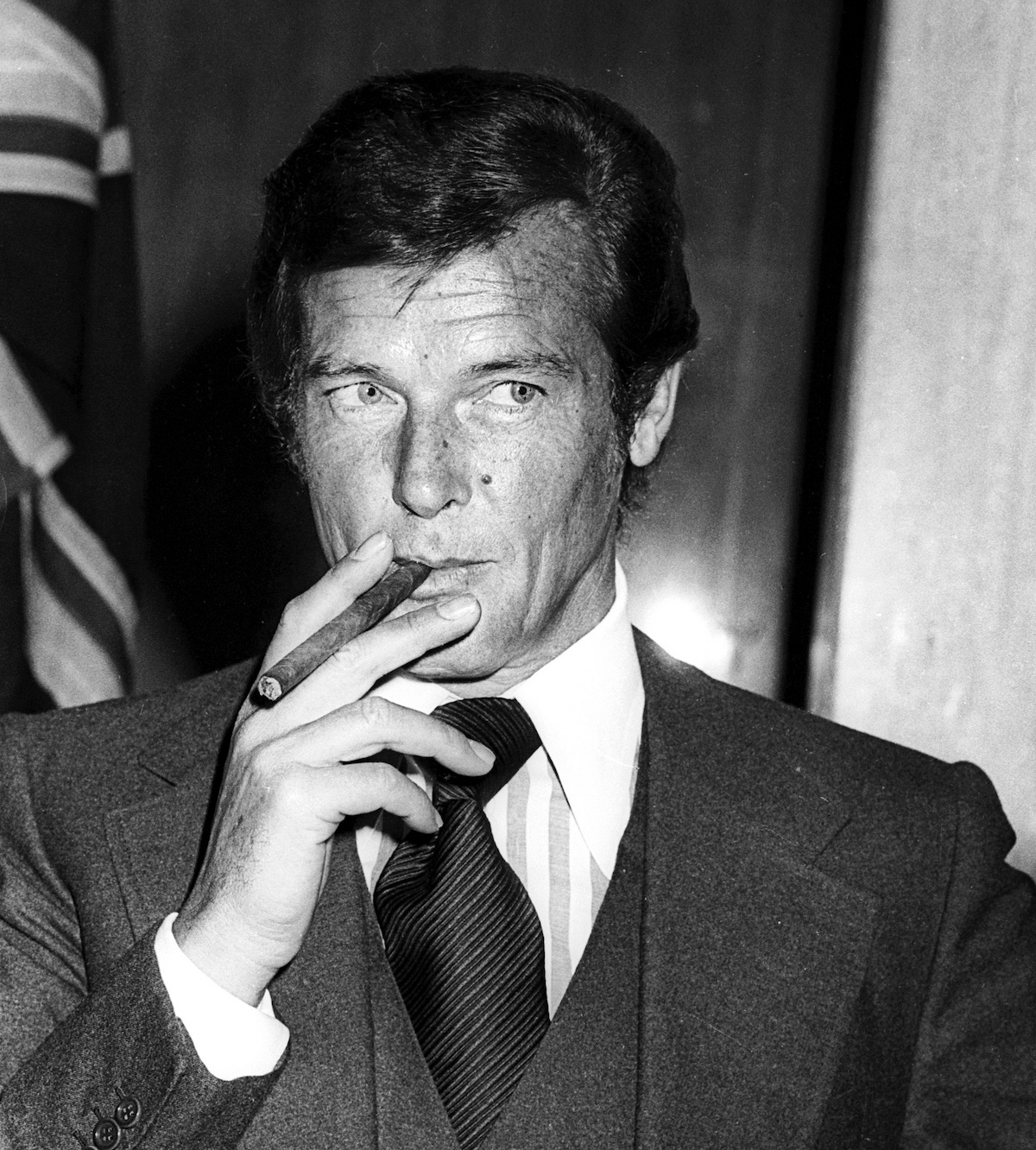

Originally published in Issue 45 of The Rake, Jemma Freeman, the Managing Director of Hunters & Frankau, tells our Editor Tom Chamberlin what she learned about the cigar business from her father, why it took her time to adapt to it, and how important it is to smoke in an elegant manner.

Cigars are so much more than a smoke. A smell in the street of a lit cigar can be a portal to childhood memories of a father or grandfather. Jemma Freeman is in a unique position: not only does she recognise such an experience for herself, but she (and her father before her) is responsible for every such experience in Britain. For every single cigar that is imported from Castro’s family island to Queen Elizabeth’s comes through her family business, Hunters & Frankau.The Rake paid a visit to the company’s London office to find out how a daughter followed in her father’s footsteps.

TC: What was the dynamic between your father and you, his only daughter?

JF: I think the way he was, girls went into one category and boys into another. It wasn’t as if we were all expected to be very good at the same things. Boys should be good at some things and girls good at others; he was quite old fashioned in some of his views on priorities for his children. People don’t expect you to be a replica of your father if you are his daughter. He and I had a good banter going, and I was not frightened of him in any way. I really enjoyed challenging what I considered a lot of his ridiculous views on what girls and boys should do.

TC: Was there a way about him that gave you permission to be rebellious, or do you think you just nurtured that sense within yourself anyway?

JF: I think he has that in him and I have that in me. He spent nine months trying to get me to go to a Swiss finishing school, and I think he was deadly serious about it, but I also think he enjoyed the absurdity of trying to get me to go to a Swiss finishing school. We had a hell of a nine months because I thought it was the most ridiculous thing. I think he pretended he couldn’t understand why I just laughed him out of the room, and then in the end he just sent me to his old school — and I think he loved the fact I went there.

TC: It must have been great that you went to his alma mater.

JF: I don’t think he thought for one minute I’d get in. I was at a very good girls’ school but wanted to leave for sixth form, like most of my friends. I think he loved that I was the third generation to go there.

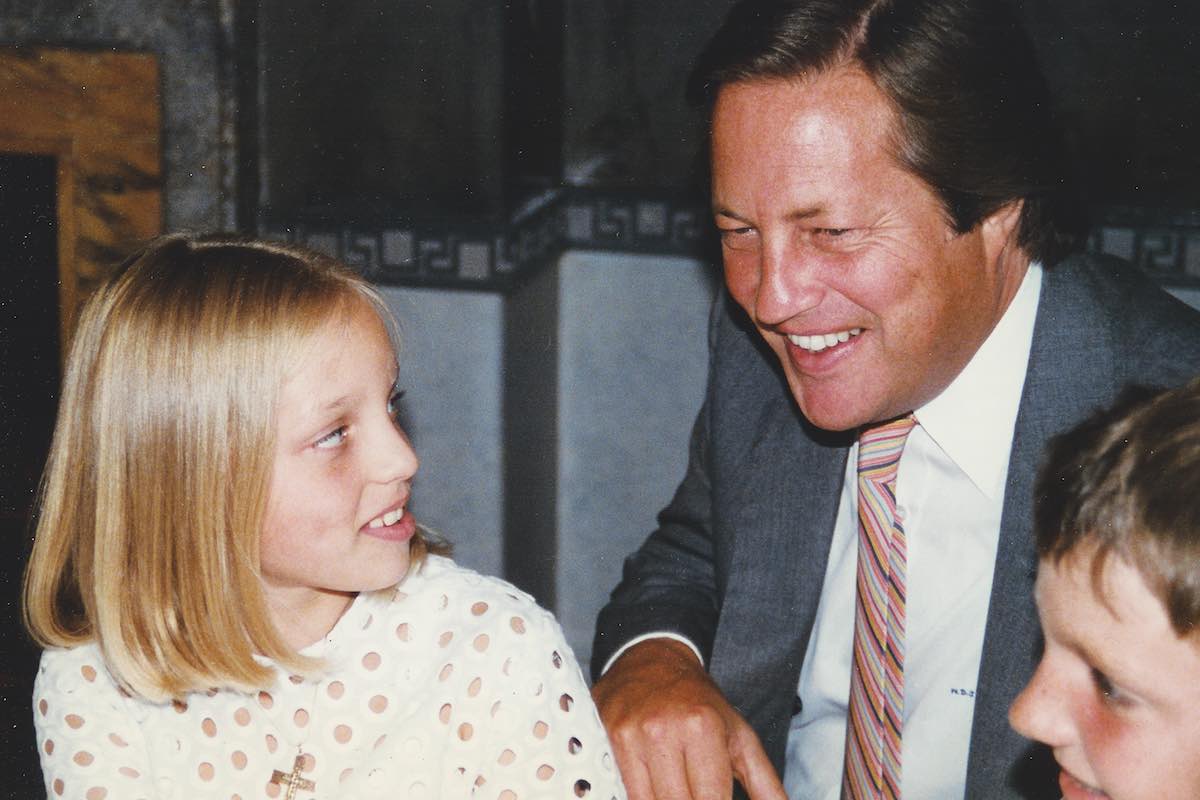

TC: I hear that when your father caught you smoking, he set you in front of a mirror and said, ‘If you’re going to smoke, do it elegantly’.

JF: Once he found out that I’d been caught smoking cigarettes he sat me down — I thought I was in a whole world of trouble — and said, ‘I’m now going to talk to you about smoking’, and then launched into his speech about how there was nothing as unpleasant as seeing a woman who didn’t know how to hold a cigarette properly. It was about the principles of smoking and how you must sit in front of a mirror and practice it. That was really important for him. It wasn’t so much that he was superficial enough to think that everything was about appearances. But he had standards, and the things that mattered to him he tried to make matter to us. The smoking thing really mattered to him — that women were elegant and presentable, and particularly his children. If we went out for dinner we would walk downstairs and the first thing he’d say to us was, ‘You’ve got one minute to get dressed; you better hurry up’. You thought you’d done your best to look presentable! He didn’t understand why people wouldn’t go to the theatre in their best. He loved creating occasions out of things. There were constantly events, and I think he wanted us to play along with those and be excited about them as he was. Sunday was always a big lunch going on — it was highly sociable, the music went on at a certain point, the Bloody Marys were made, the cigar was lit, the fire was going, people started to arrive, and there was just always something going on. He loved hanging out with people and he always included us in it.

TC: You were saying that your father had these old-fashioned views on women, but ultimately that doesn’t conform to the idea of the daughter following in her father’s footsteps. But you did.

JF: I don’t know if he had an inclination by the time he died that that was what was going to happen. He died when I was 26. I had always worked, so a few of my jobs were at J.J. Fox’s cigar shop and things like that. He also helped me get jobs. He got me a terrible job where I was a chambermaid at the Lancaster Hotel in Paris — it amused him enormously to turn up to the hotel and find me in my chambermaid outfit cleaning his bath. He found that pricelessly amusing, but I recognise why he found that amusing. I think underneath he was quite proud of the fact that I was busy working. When my father died we decided between my mother and I that it would be a good idea that while my brother finished university and his training, someone went into the business temporarily so that there was someone from the family here. I wanted to leave advertising at the time, so I said I would do it for six months if I could take another year off. I liked travelling and a year off gives you this unbelievable space to travel. So my husband and I went travelling for a year and then I came back and started work here . I was partly persuaded by the warehouse manager and his wife. I came into the marketing department and I thought I’d be here for six months or a year. I got hooked on it and became a director three years later and managing director in 2008. There’s never been any point at which I’ve worked with my father. We got on incredibly well but I think we would have driven everybody mad if the two of us were here.

TC: It almost seems like your running the business — though no joke — plays into the repartee dynamic between you two.

JF: I think he would have been very proud. I think he would have recognised that the work that’s been done here is good work. But I think if you had said to him five years before he died that in 10 years your daughter will be running this company, he would have made some off-the-cuff remark that it’s ridiculous that a woman would be capable of that. But actually what he would have thought is, ‘That’s bloody marvellous, go for it and of course you can’. There was never any doubt in my mind that he thought I was extremely capable, but he just wasn’t somebody that applied pressure. He would be much more concerned about if you knew who the prime minister was and that you engaged in day-to-day life, and smoked elegantly.

TC: So he did not see you as a housewife?

JF: I don’t think that’s what he wanted, I think he recognised that’s what I wanted . I think he had a romantic vision of a daughter in some ways who had this lovely sort of life and ended up marrying a baron with a nice shoot. He would have loved that. He also would have loved the fact that that’s exactly what didn’t happen. I could wind him up just as much as he could wind me up.

TC: How do you see your relationship with the business?

JF: I think it’s shifted hugely. It’s taken me a long time but I feel now more comfortable with my role in the business and I think I understand better what I can do for the business. I feel less now like the business is controlling me and more like I’m in a position where I have a bigger perspective on what we’re doing and where we’re going. That’s taken a while in a different way to my father, who made the business what it was. I think he loved it in the same way as I do, he loved the whole thing about Cuba, he respected them and enjoyed the people he knew in Cuba and he loved being involved with cigars. I think, a), he loved them, and b), it’s a very unusual world to be involved in, there’s nothing else I’ve found quite like it.

TC: What about cigars and smoking, was that part of family life?

JF: My mother’s a cigarette smoker and my father smoked cigars. There were cigars everywhere in our house. They had this drinks cabinet in their drawing room and every evening he’d come home and the first thing he’d do is have a whiskey and the drawers would open and you’d hear the tubes rolling, and then you’d know he was home. He’d drive my mother insane, like so many cigar smokers do, by sitting in an armchair and never quite getting to the ashtray in time, and constantly saying things like, ‘Ash is good for the carpets, darling, don’t worry about it’. He had a couple of rules, which were if you ever go into a restaurant and there’s a humidor, always take the worst cigar so nobody else has to end up with it. That was a family rule when we went out for dinner. He knew that the cigars would have come from him, so he didn’t want the bad one sitting in the humidor. I remember being on a beach in America once, my mother smoking a cigarette. And then, out of the distance, this person comes up to us and says, ‘I’m deeply offended by this cigarette smoke’ — and she’d come from 150 feet away. My father quietly went into his pocket and took a very large cigar out and said, ‘Well, I suggest you move yourself upwind of this, then’, and off she went. I think for him with cigars he loved the whole world. He loved Cuba, he loved the people he met, he thought they were all amazing. I don’t know why because he never really spoke any Spanish. He once said, ‘I’m going to teach you how to speak Spanish today — what you do is add an ‘o’ or an ‘a’ to the end of any word and you’re pretty much there’. He had this ability to sit in a restaurant with a Cuban, neither of them speaking a word of the other’s language, and end up best friends, and that was what was so compelling about him — that you wanted to be in his company. He had more ideas than anybody, he was a serial entrepreneur. He was friends with the Roux brothers, and they went through a long period of time developing posh boil-in-the-bag food, they used to pot about in the kitchen and he was absolutely convinced this was the future of food, and nothing ever came of it. He had this other thing, which was deodorant for secretaries. He called it ‘Pit Stop’, and it was a miniature bottle with a black-and-white flag on it, and he couldn’t understand why nobody agreed that Pit Stop was the greatest invention ever and should be carried around by everyone. He loved gadgets. He always said he had the first ever car telephone, my father. It had an aerial off it like you find on a tank. The minute anything came out he bought it, he always had the first model and it never worked. One of the great tragedies of someone like that dying young is that he had about another 20 years of really good ideas, and that’s the thing I almost miss the most — that spark of his brain, because it was always interesting to be around. The way he thought was extraordinary.

This interview originally appeared in Issue 45 of The Rake.