The Buddha of Mount Street: Doug Hayward

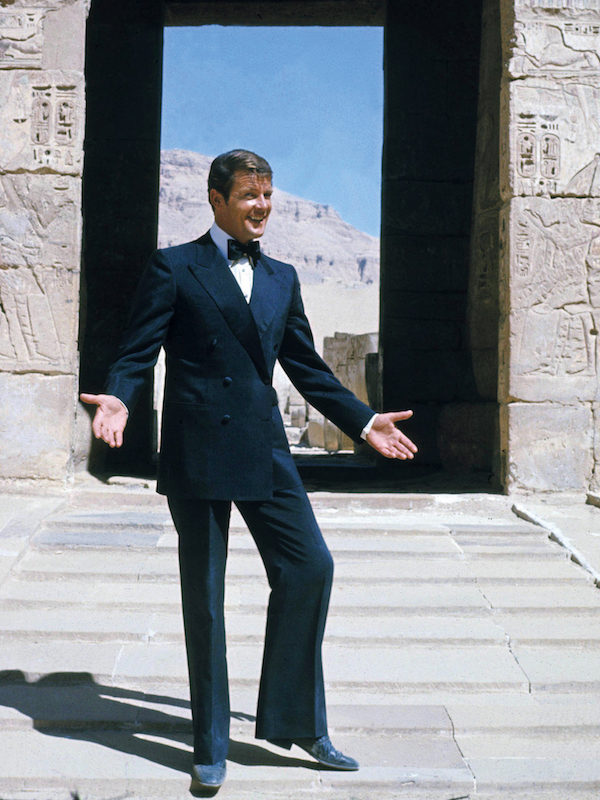

Doug Hayward was the ‘showbiz tailor’, a man who rose from modest surroundings to clothe and befriend stars of the sixties such as Michael Caine, Terence Stamp and Roger Moore.

"A working-class hero is something to be,” declared John Lennon in his song of the same name. Doug Hayward didn’t make Lennon’s suits — that honour fell to the more celebrated sixties Savile Row insurgent Tommy Nutter — but he would surely have concurred with the sentiment. Hayward’s distinctive sense of style was shaped by a working-class childhood, when labouring men like his father, who cleaned boilers at the BBC, stood straighter and walked taller when they went out on Friday night in their best, and only, suits. And while Hayward’s tailoring establishment in Mount Street would eventually clothe men across the social scale — from friends and fellow upstarts like Michael Caine, Terence Stamp and Terry O’Neill to Sir John Gielgud and lords Lichfield and Weinstock — he never forgot his roots. “He knew what it was like to be dirt-poor,” says Audie Charles, the director of Anderson & Sheppard’s Haberdashery, who worked with Hayward for 30 years. “For all those guys — Michael, Terry and Doug himself — no matter how famous they got, there was always the feeling that someone was going to tap them on the shoulder and say, ‘O.K., you shouldn’t be doing this, get back to where you belong’. They all felt like they’d found a lucky ticket. And, in many ways, Doug was at the centre of it all. He epitomised that sixties explosion.”

Hayward had grown up in Hayes, on the edge of London; he won a place at Southall Grammar School but decided to leave at 15, to “learn a trade”, as one did in the early fifties. “We didn’t have a careers master,” he later recalled, “but I found a booklet that listed possible occupations. I went down the list and when I got to T for tailor, I thought, ‘I don’t know any tailors. I can’t ever be judged as being a bad or good one, so I’ll be a tailor.’”

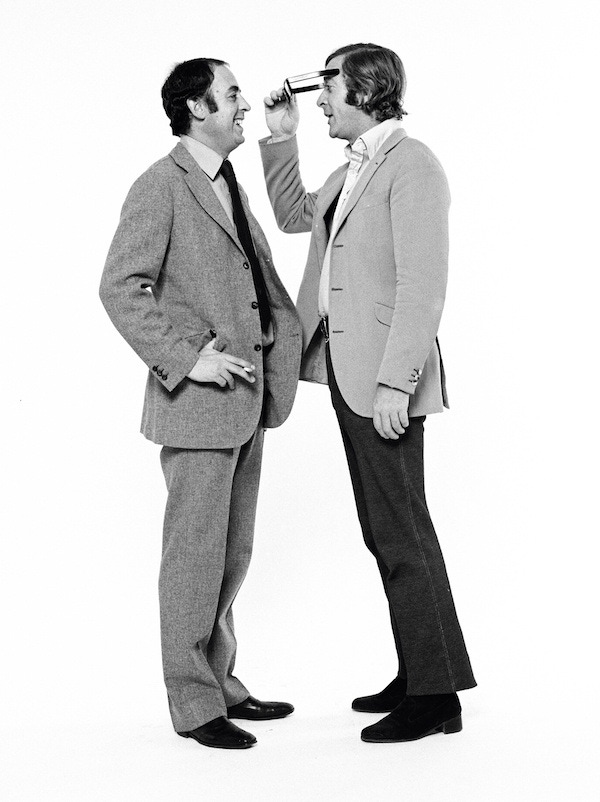

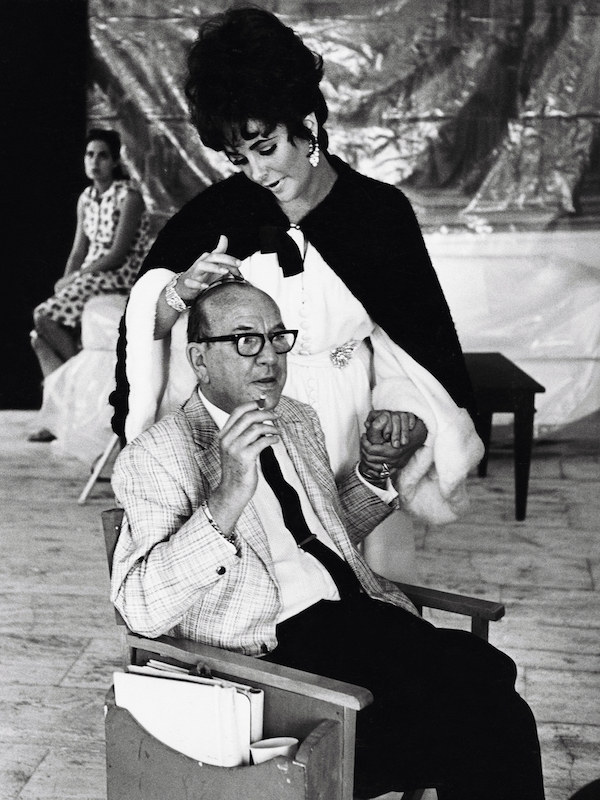

He served an apprenticeship with Dimitrio Major in Fulham, tailors to the theatrical set; early clients like Peter Sellers and Stamp came via the BBC at nearby Lime Grove, or through Hayward’s first wife, Diana, sister-in-law to the film director Basil Dearden. When it came to his own premises, he shunned Savile Row — “he resented the snobbishness and the hierarchy and the condescending manner,” Charles says — in favour of a house at 95 Mount Street in Mayfair that Stamp found for him. “Mount Street was like a little village then, in 1967,” Charles says. “There was a chemist, fish shop, dry cleaner, post office, and a little hardware store. People would pop in between the bank and the butcher’s. It was a kind of social hub.”

With its grey flannel walls and profusion of sofas and easy chairs, the Hayward front room, designed by George Ciancimino, was part gent’s club, part salon, with Hayward very much presiding; he lived above the shop and would often descend, toast in hand, his Jack Russell capering at his feet, to make people tea. “You’d get such amazing combinations of people in there,” Charles says. “Michael Caine, Roger Moore, Michael Parkinson, Johnny Gold and Mark Birley, all nattering together. Alec Guinness sitting with a cup of tea. The racing driver Jackie Stewart alongside a famous heart surgeon, chatting away. One client kept his whisky in the cupboard and would sit with his feet up doing the Times crossword, waiting for someone he could go to lunch with. It was like the social networking of its day.”

Hayward became known as the ‘showbiz tailor’, and his star rose in tandem with his clients, thanks to his fearsome work ethic — he would nip to the Dorchester in his secondhand Mini to fit the likes of Sydney Pollack and Clint Eastwood — and his unstuffy air. “He had a knack of just slotting in, whether he was talking to dukes, earls or builders,” says Charles. O’Neill called Hayward the Buddha of Mount Street: “He was someone you were naturally drawn to, very charismatic, and he would do anything for you. He was probably the best-loved man in London.” Caine borrowed some of Hayward’s vibrant insouciance when playing Alfie. “Doug and Michael shared a dinner suit,” Charles says, “because they shared the same measurements, as well as a flat, and more than a few women.” Hayward was also the template for Harry Pendel, as described in John le Carré’s The Tailor of Panama: “It was in the face that the zest and pleasure of the man were most apparent. An unrepentant innocence shone from his baby blue eyes. His mouth gave out a warm and unobstructed smile. To catch sight of it unexpectedly was to feel a little better.”

Then, of course, there were the suits. Hayward was a large-ish man who favoured country checks — James Coburn called him “the Rodin of tweed” — and he would focus on the character-actor likes of Sydney Greenstreet rather than Cary Grant or Fred Astaire. “‘Who was his tailor?’,” Charles reports Hayward as saying of himself. “‘He was a large man who always looked good’.”

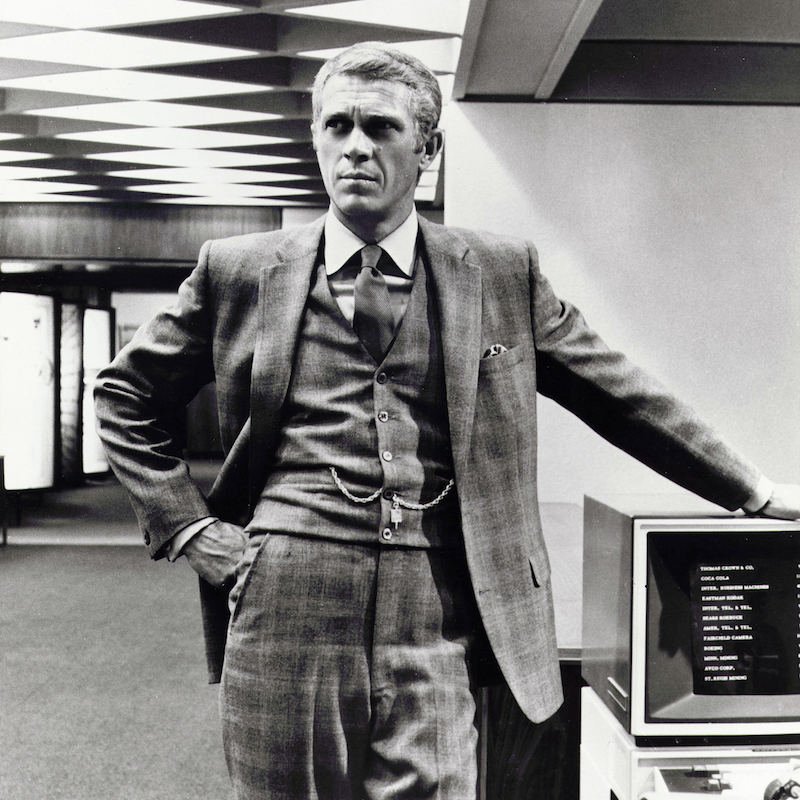

“Doug didn’t want to emphasise the waist on jackets, so they’d be slightly flared at the bottom,” says Leslie Haynes, a head cutter at Anderson & Sheppard who worked with Hayward for three decades. “And they had a lower button than most of the other Savile Row tailors had, so they weren’t quite as structured, and were lighter and easier to wear. His DB was always a button-one, show-two. They reflected the times, in that things were loosening up, but he was never trendy. He was very specific about what he wanted, and he stuck to his guns. You can spot his suits on Michael Caine in The Italian Job and Roger Moore in The Spy Who Loved Me a mile off.”

Charles adds: “He was a brilliant observer, noting how someone acted away from the mirror. You know, whether their shoulders slumped, how they shoved their hands in their pockets, how much their belly came out. It was the uncorrected stuff that Doug addressed, and that’s why his cut and silhouette was so flattering.” Hayward would stress as much to the tailoring students he later taught at the Royal College of Art: “You can’t do anything unless you can cut.”

Hayward’s social ease meant he was as at home having a Sunday morning kickabout with his impromptu football team, the Mount Street Marchers (football had been his first love, and Bobby Moore was another client), as spending weekends on Mustique with Princess Margaret (he treated the latter, he said, like a “regular bird”, crooning word-perfect Noël Coward renditions while she plunked away on the piano). He continued to live in Mount Street until his death in 2008, shortly after being diagnosed with dementia; the shop closed down in 2014. “I think Hayward pretty much died with Doug, because his personality was central to its success,” says Charles. “It’s like Mark Birley: you went along to experience the aura of the man as much as the things he offered. He was a one-off.”

One of Hayward’s favourite stories concerned his redoubtable mother, Gladys. Convinced that he was running a brothel or a gambling den out of Mount Street, she kept all the hard cash he funnelled to her in a bunch of ice cream boxes under her bed. After her death, the stash was found, along with a note: “This money is to get Doug out of prison when they finally get him.” That they never got Doug Hayward is a tribute to his ability to seize the moment and run with it, and to create a new breed of sartorial hero — working-class or otherwise — in his own snappily whistle-and-fluted image.