BIG-TIME CHARLIE: The Beistegui Ball

One critic likened it to a ‘moral indecency’; those who were there were so consumed by the opulence and theatricality that they had no reason to care. The night in question — September 3, 1951, in Venice — has gone down in history as the party of the century. Originally published in Issue 42 of The Rake, Nick Foulkes delves into the life of Don Carlos de Beistegui, an aesthete of some repute who used his riches to keep the reality of war and sacrifice at bay.

About the only thing that unites the two evenings most often described as ‘the party of the century’ is the height of their hosts. Neither Truman Capote nor Charlie de Beistegui were tall men, but there the similarity ends. The former’s Black and White Ball at the Plaza Hotel in New York was the prototype of the modern celebrity party, thrown by a man whose early promise as an author was betrayed by his social ambition. The Beistegui Ball in Venice on the night of September 3, 1951 was an altogether different matter, thrown by the greatest aesthete of his age.

Don Carlos de Beistegui, or Charlie, as he was known to his circle of intimates (of whom there were few), was one of a small group of cosmopolitan plutocrats who dominated European high- life in the years between the second world war and the beginning of the Jet Set era. They swept into mid 20th-century Europe on a tide of money. Their fortunes, built on the backs of labourers in Central and South America, may have come from unpleasant and malodorous beginnings in silver mines or the exploitation of centuries-old deposits of guano, but they dissipated them in Europe with style and liberality. In the first half of the 20th century the words ‘South American millionaire’ had much the same ring to them as ‘Russian oligarch’ or ‘Chinese billionaire’ have today.

Charlie, though Mexican by birth, never set foot on its soil. His grandparents left after the execution of Emperor Maximilian in 1867 (an event chiefly remembered today as the subject of Manet’s famous painting), and Charlie was born in Paris in 1895 and then educated at Eton. To add another layer of cosmopolitan shellac to the already exotic marquetry of his origins, while Beistegui’s father was Mexican ambassador to Madrid, the King of Spain persuaded his mother to take Spanish nationality on the grounds that as Spain had discovered it a few hundred years earlier, Mexico was still, au fond, Spanish territory. “He was,” said one of his friends, “a Mexican who thought he was an Englishman who was living in France.”

If Beistegui’s life could be summed up in a word, it would be ‘effect’. In two, ‘decorative effect’. During Les Années Folles, he was the talk of Le Tout-Paris. Described by Sir Cecil Beaton as “a dazzling hodgepodge of Napoleon III, Le Corbusier modernism, mechanism and surrealism”, Beistegui’s Le Corbusier penthouse apartment on the Champs-Élysées was a fairytale fantasy of blackamoor statuary and mirrors; crystal girandoles and objets de vertu; and obelisks and jewels. A perfectionist, he had even sent sketches of his own to Le Corbusier to give the high priest of modernism something to work from.

But what stunned visitors was the terrace. Writing about it a generation later, Beaton was still astonished: “Certainly, never before had anyone seen the like of Beistegui’s terrace. After mounting a white spiral staircase, the visitor pressed an electric button that caused a glass wall to roll back. Thus was revealed a terrace that overlooked the traffic and the lights of the Champs- Élysées. It was furnished with Louis Quinze furniture that had been painted white and placed on a grass carpet open to the sky.” He had created an open-air drawing room complete with fireplace and parrot.

Today, Beistegui would be called an interior designer or a stylist. Beaton called him “a pasticheur par excellence”. But there was more to him that: he could draw, he could write poetry, and he had taste — taste that was theatrical, original and abundant. Moreover, he had two other qualities that shaped his aesthetic: he was selfish and extraordinarily rich. Like some latter-day creation of J.K. Huysmans, he used his Croesan riches to keep reality at bay. His apartment on the Champs-Élysées was just an amuse-bouche, a bit of juvenilia when compared to his chef- d’oeuvre, the Château de Groussay, an hour or so outside Paris, which he bought in 1939 — Beistegui was above worrying about such vulgar interruptions as world wars and the ambitions of murderous dictators.

Groussay was as much an idea as it was a house, a stage upon which Beistegui starred in the lavish costume drama that was, by all accounts, one of the most civilised lives of the 20th century. Recording a visit to Groussay in his diaries, Beaton described Groussay as “a recreation created against, and to spite, the present times”.

Behind the château’s façade, Beaton found “a long-discarded Victorian England peopled with Beistegui’s French, Spanish- Mexican and South American weekend guests. They wear English tweeds, English cashmere jerseys, English brogues. They skim through the Illustrated London News and walk on lawns until it is nearly lunchtime, when tasselled footmen serve marrow or drippings on toast with a glass of Madeira. Conversation is mainly about those who do, or do not, possess great taste — or great furniture. The host does not encourage political argument or controversial or inflammatory subjects. Unfashionable pursuits or unpopular personalities are distasteful. Here is a place where, at whatever cost — and the cost must be astronomical — the outside is determinedly kept at bay.”

Beistegui had created a quasi-baronial Anglomaniacal Neverland, with antlers crowding the walls of the hall, a billiards room, great potted ferns the size of palm trees, and, most impressive of all, a galleried library with rich red walls. During the 1950s he decided it would be amusing to add a theatre to Groussay, so he built one modelled on the Margravial opera house of Bayreuth in Germany, a dazzling wedding cake of a creation, swagged and tasselled, a riot of red velvet and violet damask silk, lit by elaborate glass sconces and giant chandeliers. It was not that Beistegui particularly cared for the theatre or the opera; there were only ever two performances. For the restless Beistegui, the act of creation was what mattered, and he was happy to sit in the empty theatre raptly admiring his sumptuous surroundings.

Guests were staggered by the luxury of it all. One effusive American visitor to Groussay said that she didn’t “know a finer room than the library at Groussay, which is three floors high”. It was an obsessively detailed, idealised vision of what an English stately home of the late Victorian period might have been like had its owners been European sybarites of unlimited means and exquisite taste. It was a perfect work of art that perfectly expressed what was being talked about as ‘le goût Beistegui’, and what made it extraordinary was that it had been completed during the second world war.

Throughout the war his diplomatic passport — he served as cultural attaché at the Spanish embassy — granted him immunity from the depredations visited upon the rest of France. A chandelier arrived in the diplomatic pouch from Madrid. Amazingly, a roll of chintz came from England in May 1940, the same month as the Dunkirk evacuation. There were those who said that work on Groussay during the war kept a small army of craftsmen from deportation — “without Charlie,” one friend observed, “the upholsterers and painters and carpenters and carpetmakers would have been sent to Germany as slave labourers.”

With Beistegui as Prospero, Groussay was an enchanted island of elegance and comfort, while the tides of history eddied and swirled outside its walls. While the rest of Europe starved and froze, Beistegui entertained as before — the château heated by stoves and roaring fires, the highly polished dining table laid with Meissen china and laden with good food. While others grew thin during the war he became quite corpulent. “During the war, Groussay was a refuge, a paradise,” recalled one of his friends, Gabrielle d’Arenberg, when talking to Dominick Dunne of Vanity Fair. “He had chocolates and wonderful food and soap sent through the Spanish embassy. Even curtains for his drawing room were sent from Spain. It was absolutely glamorous. Cocteau would be there, and Christian Bérard, and all the people who were interesting at the time.”

But while the life he enjoyed may have been vicuña soft, according to many Beistegui’s heart was of adamantine hardness. “Beistegui is utterly ruthless; such qualities as sympathy, pity or even gratitude are completely lacking,” Beaton wrote in his diary, adding for good measure that, “He is without doubt the most self- engrossed and pleasure-seeking person I have met”. There were some who saw a more sensitive side to a man who wrote poetry and, for all the sumptuousness of his life, slept in a bedroom filled with the simple furniture of his childhood and who was capable of acts of great warmth and kindness.

However, that was a side he chose to keep well hidden, so it is for his grands gestes and coups de théâtre that he is remembered, none of which was more memorable than the famous ball in Venice.

In 1948 he had happened across the crumbling Palazzo Labia, and, as he walked into the once-grand, dilapidated ballroom, with its flaking frescoes and peeling walls, he was able to see beyond the years of neglect. According to Life magazine, he bought the palace for a reported half a million dollars and spent another three-quarters of a million dollars doing it up.

Then, in the spring of 1951, cards inviting everyone from New World film stars to Old World nobility began to arrive, requesting the honour of their presence at half-past-ten on the evening of September 3 at the Palazzo Labia for an 18th-century costume ball at which masks would be worn. In all, 2,000 of what Life dubbed “the world’s most blueblooded and/or richest inhabitants” were invited.

However, it would have been a mistake for anyone to regard this as a jolly evening on the Grand Canal underwritten by an eccentric millionaire. “Ce n’était pas un bal pour s’amuser,” says Jacqueline de Ribes, who attended the ball as a young woman. “It was a ball to be happy. It is quite another word. It was a ball to be happy. But not for fun.”

For Beistegui, his guests were little more than living pieces of furniture with which to dress his Venice creation; as well as wearing costumes, they would also have to make an entrance ... literally present a tableau vivant, which would require careful thought and could involve a dozen other, appropriately costumed, guests. The contrast with the drab backdrop of life in Marshall- Plan Europe could not have been greater, and when Diana Cooper asked if she could bring General Marshall as her guest, Beistegui asked, apparently in all seriousness;

“Is he from a good family?”Already being bruited as the most lavish party since before the war, it fell at a unique point in European history. The scars of the conflict that had gouged deep into Europe’s emotional and physical fabric had barely begun to heal. A generation of Europeans would grow up experiencing a life of drab, grey uniformity. The Iron Curtain was beginning to go up, and over everything loomed the growing threat of a new world war waged with yet more sinister weapons than had devastated Europe a few years earlier. But Beistegui was not someone to be concerned with the dreariness of little lives, and if anyone could find a way of getting enough chintz in the aftermath of nuclear Armageddon ...

“At the time, Beistegui’s fête seemed like a moral indecency,” David Herbert, the British socialite and memoirist, would later write. Perhaps Cocteau put it most neatly when he said of the half a billion francs Beistegui was spending: “It costs about as much as a warplane, and I prefer a ball (provided I don’t have to go).” Beistegui had found there was not a problem that could not be solved with money: 200 million francs for ‘popular entertainments’ on the evening of the ball had even won round the communist mayor of Venice.

Beistegui found himself catapulted from the relative obscurity of his circle of aesthetes and aristocrats to the eye of a media storm. He became known variously as the Count of Monte Cristo or, more prosaically, the ‘mystery millionaire’.

Venice never had and never would again see anything like it. Over the coming days the city would witness the sort of grandiosity, imperious behaviour and outrageous displays of opulence not seen since the days of the doges. Only the doges did not have to contend with the world of colour magazines and gossip columnists, who were drawn to Venice like iron filings to a magnet.

Life could not contain itself. “This month in the most splendiferous party of 1951, Venice returned to the pomp-packed days of its doges,” it trilled, adding in conversational argot that would have caused Beistegui a shiver of horror: “Newspapers all over the western world headlined the blowout, and the hearts of would-be socialites all over Europe were broken in the scramble for invitations.” Time magazine added: “By 10 p.m. of the great night, the canal in front of the palace was choked with gondolas and motorboats. Floodlights limned the arriving guests while gapers gawked from windows made available by neighbouring palace owners at up to 80,000 lira a head.”

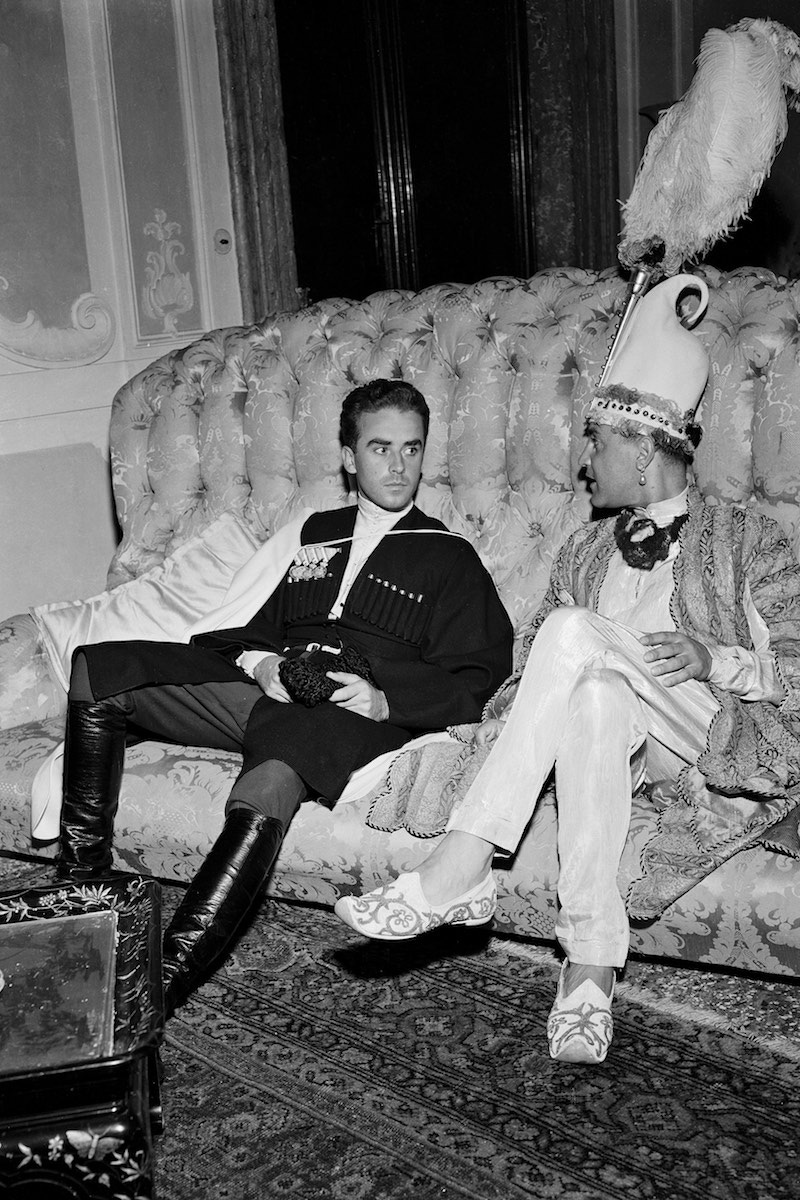

“It looked unique,” recalls Jacqueline de Ribes. “That night every window in the palace was lit the same way it would have been in the 18th century, and not by electricity.” The Duchess of Devonshire wrote to her sister Diana: “I must say, it was fascinating in its way, and the ball itself a real amazer.” Even the private detective who screened each guest on arrival was in period clothes. Anyone who did not adhere to the dress code was quickly whisked out of sight, though most people had invested months and huge sums in their costumes — this was fancy dress as an Olympic sport, and just as competitive. Arturo López Willshaw, the multi-millionaire scion of a Chilean guano dynasty who lived in an intriguing ménage with his wife, Patricia, and his wan young lover, Baron Alexis de Redé, was said to have spent $55,000 on a set of costumes that represented an 18th- century Chinese ambassador and his wife. Of course, his lover, de Redé, was a member of the party, clad in robes embroidered with real gold thread, along with a number of other friends and relatives as attendants ... all with masks and excessively long false fingernails, their entrées enhanced by accessories such as songbirds in gilded cages.

The most haunting costumes were created by Pierre Cardin for Salvador Dalí and Christian Dior. Under the name the Phantoms of Venice, their entrée comprised six towering and one short white-robed, skull-visaged, black-hatted spectres. For extra effect, Dalí wore a pair of double-glazed spectacles with ants teeming between the two panes of glass.

Memories of the ball, and of the spectacular entrées, would last a lifetime. “Daisy Fellowes, regularly voted the best-dressed woman in France and America, portrayed the Queen of Africa from the Tiepolo frescoes in Wurzburg,” recalled the Duchess of Devonshire in 2010. “She wore a dress trimmed with leopard print, the first time we had seen such a thing (still fashionable today, 60 years on).” She accessorised this memorable outfit with her famous ‘Hindu necklace’, a platinum-set suite of jewels by Cartier combining diamonds, emeralds and sapphires in the fashionable ‘tutti-frutti’ style. She completed her outfit with a phalanx of scantily clad male attendants.

And standing there, at the top of the stairs, was the host. Beistegui was transformed from his normal 5’6” in height to nearly seven-feet tall in giant 16-inch platform shoes concealed by scarlet robes of a Procurator of the Venetian Republic, his disdainful features framed by the curls of a huge wig that cascaded over his shoulders and down his chest. Life reported that he changed his costume six times over the course of the evening, though Jacqueline de Ribes can remember only two changes: his wigged and buskined incarnation as the Procurator of Venice and another costume that transformed the pint-sized plutocrat into a doge.

This article originally appeared in Issue 42 of The Rake.