Method in the Madness: Sir Daniel Day-Lewis

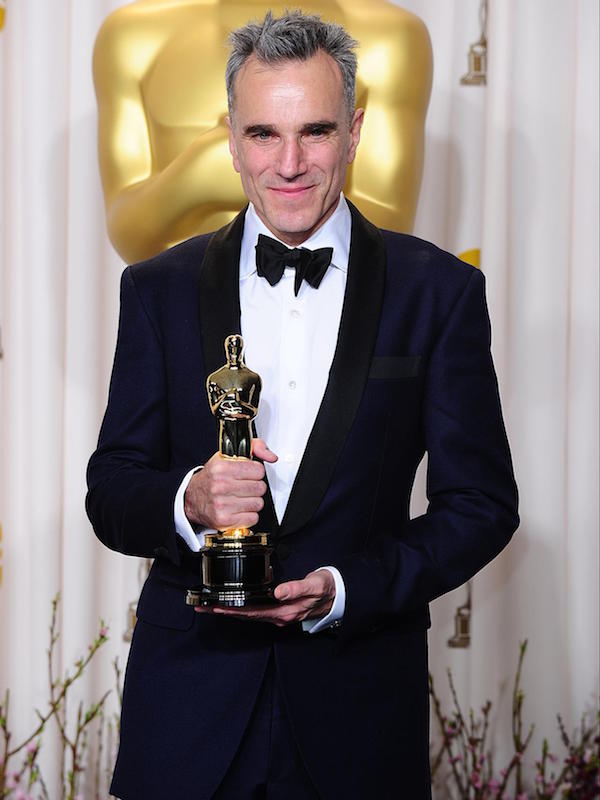

As our month’s coverage of eminent, experienced gentlemen draws to a close, we celebrate acting’s greatest craftsman, Daniel Day-Lewis.

A dandy dresser, an iconoclast, an aficionado of craftsmanship, an uncompromising individual who plays by his own rules, refusing to accept anything but the best — so particular, so choosy, that he’s made a scant 16 movies in the past 30 years. There are few actors working today who, in their work and life, are as in step with the major philosophical touchstones of The Rake as Sir Daniel Day-Lewis.

The son of poet laureate Cecil Day-Lewis and actress Jill Balcon, Daniel Day-Lewis was born to a life of the mind — though not one of enormous privilege, his father’s occupation hardly being the most lucrative of professions. He first honed the skills of mimicry that are an actor’s stock-in-trade growing up in Greenwich, London, where he was bullied for his apparent poshness, reacting by adopting the mannerisms and accent of his scrappy peers, as well as certain of their destructive, petty criminal habits.

“I was a savage for so many years of my life,” Day-Lewis said. “I broke things to get attention.” Nevertheless, the duality of his youth had its upsides for the future performer. “One of the great privileges of having grown up in a middle-class literary English household, but having gone to school in the front lines in Southeast London, was that I became half street-urchin and half good-boy at home. I knew that dichotomy was possible.”

"I became half street-urchin and half good-boy at home. I knew that dichotomy was possible.”Naturally intelligent, well-bred, erudite, a bit naughty, a chameleon changing his image to suit the setting — so far, so rakish. The rebellious lad was soon packed off by his exasperated parents to board at the exclusive, selective Sevenoaks School (one of Britain’s costliest institutes of learning) where he inevitably rebelled, moving after a couple of years to the more creatively focused Bedales, at which point his nascent interest in acting took hold. His first role, a bit part in the movie Sunday Bloody Sunday at age 14, allowed Day-Lewis to indulge both thespian and tear-away tendencies — he was paid to vandalise a series of cars on camera. (“Heaven,” he called it.) After graduating, said Day-Lewis, “For about a year, I just didn't know what to do. I did laboring jobs, working in the docks, construction sites.” A career in woodworking strongly appealed for a time, but Day-Lewis came to realise that “If you have a certain wildness of spirit, a cabinet-maker's workshop is not the place to express it.” So it was that he settled on his other keen interest, acting. “At a certain age it just became apparent to me that this was probably the work that I would have to do,” he said. “When I did make the decision to focus on acting, I think my mother was just relieved for me that I had finally started to focus.”

Day-Lewis first earned his spurs on the London stage, before winning several television roles, and making his first major movie appearance in the acclaimed 1982 biopic, Gandhi. His reputation grew with star turns in lauded art-house film My Beautiful Laundrette and the Merchant-Ivory production A Room with a View (both 1985), Day-Lewis cementing leading man status in the 1988 Milan Kundera adaptation, The Unbearable Lightness of Being. The following year, his Best Actor Oscar-winning performance in My Left Foot would display (particularly when contrasted with his variety of previous roles) the depth and breadth of Day-Lewis’s talent.

The immersive method-acting approach Day-Lewis would become famous for first became apparent while shooting My Left Foot, where he remained in character as the cerebral palsy stricken writer Christy Brown throughout filming, insisting on being carried about in a wheelchair and spoon-fed. For 1992’s The Last of the Mohicans, he spent months learning to hunt and live off the land, just as his Native American-raised character would’ve. (Director Michael Mann said Day-Lewis maintained a strict diet: “If he didn’t shoot it, he didn’t eat it.”) During filming of the Guildford Four’s story, In the Name of the Father, he spoke with an Irish accent 24/7, drastically lost weight eating only prison rations, confined himself to a gaol cell, submitted to fierce mock interrogations, and instructed crew to heap abuse upon him, all in order to remain in character as the falsely convicted and imprisoned Gerry Conlon.

“I suppose I have a highly developed capacity for self-delusion, so it's no problem for me to believe that I'm somebody else,” Day-Lewis remarked. “I have always been intrigued by these lives I have never experienced.”

In one of his most rakish moments of preparation, in 1993 the actor stalked the streets of New York for several months dressed in late-19th-century regalia — period tailoring, a cape, top-hat and cane — while readying himself for the Martin Scorsese rendering of Edith Wharton novel, The Age of Innocence. For Scorsese’s 2002 Gangs of New York, Day-Lewis (playing a brutal gang-leader) learnt how to butcher animals, studied knife throwing with circus performers — and caught pneumonia as a result of refusing to wear any warm modern garments on set.

“I’m a little bit perverse, and I just hate doing the thing that’s the most obvious.”“I avoid talking about the way I work,” he’s said of his prep for roles and strict on-set discipline. “But in avoiding it I seem only to have encouraged people to focus their fantasies about me in an ever more fantastical way.” Often described as one of acting’s greatest living craftsmen, during a hiatus from film in the late 1990s, Day-Lewis immersed himself in another craft altogether, embarking upon a full apprenticeship with the late, great Florentine shoemaker, Stefano Bemer. “I’m a little bit perverse, and I just hate doing the thing that’s the most obvious,” he’s said. Day-Lewis retains a deep passion for handcrafted footwear; he’s a loyal customer of British bespoke cordwainer George Cleverley, whose shoes he will wear throughout his next film — an as-yet-untitled project centred on the 1950s New York fashion industry, directed by Day-Lewis’s There Will Be Blood collaborator, the gifted auteur Paul Thomas Anderson. Considering the rigours he’ll doubtless impose upon himself in pursuit of the perfect performance, we’re glad at least that Day-Lewis will enjoy enormously comfortable footwear throughout the shoot. This most rakish, dedicated of actors deserves at least that small mercy.