A Man of Many Parts: Gabriele D’Annunzio

The Rake examines the life of Gabriele D’Annunzio: a raffish gent whose capacity for untrammelled theatrics was exceeded only by his yen for style — at least, when opting to wear clothes.

Prolific poet, prince, politician; rampant philanderer, pilot, flâneur and fame hunter; home decorator, thrill-seeker, romantic, rogue; conman, cocaine addict, social climber and proto-Fascist — Gabriele D’Annunzio’s exotic and overwhelming tendency to aestheticise every aspect of his life places him on the verge of being a parody of the worst vices of the stereotypical Italian male. Even today, 76 years after his death in 1938 at his Lake Garda villa — the estate a gift from the Italian government — he remains a controversial and divisive figure in Italy: for some, a symbol of all that is irrational, corrupted and decadent; for others, the blueprint of an appealingly louche mode of living that is integral to some quarters of Italian culture.

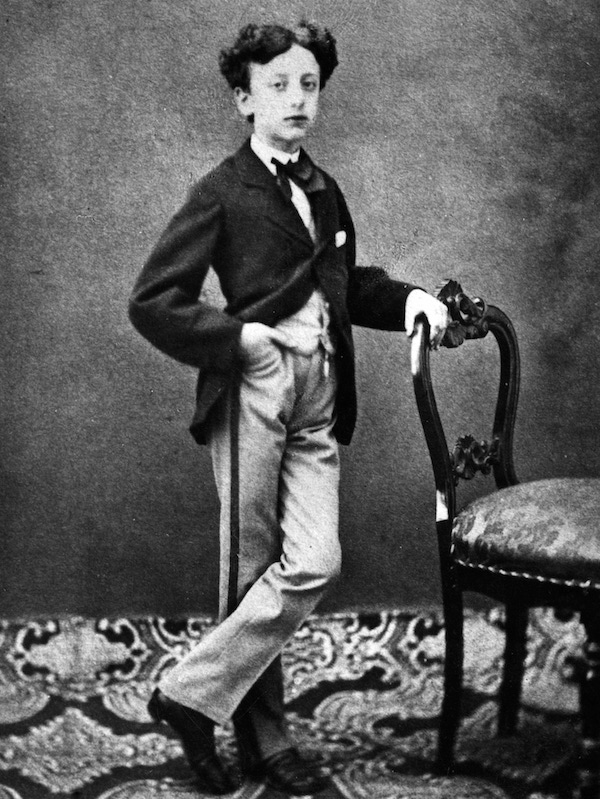

D’Annunzio was born in 1863 in the Italian city of Pescara, where his father was Mayor as well as being a landowner and wine merchant, a figure whom D’Annunzio later despised for his self-indulgent excesses. Certainly, D’Annunzio was a self-made — indeed, self-obsessed — man, unflaggingly conscious of his image to the point of preposterous vanity. He declared himself to be Italy’s greatest poet since Dante, and likened himself to Caesar, Nelson and Byron. He wrote to the newspapers giving news of his own tragic death following a fall from a horse in advance of the release of his first publication, just to drum up publicity. And, he was a die-hard disciple of Baldassare Castiglione, the author of the 16th-century The Book of the Courtier, in which the writer posited what he referred to as the ‘universal rule’ in all human affairs — sprezzatura, a facade of nonchalance that concealed the artistry required to pull off challenges with aplomb, regarded even at the time as both romantic and deceptive in almost equal measure.

D’Annunzio clearly lived out Castiglione’s doctrine, which was described, disparagingly, by Henry James as “beauty at any price, beauty appealing alike to the sense and the mind”. As much as his often violent and sexually explicit books titillated, D’Annunzio himself aimed to make a quick and forceful impression: short, balding, with discoloured teeth and a high-pitched voice, he countered his shortcomings by always being formally dressed — as men of his rank, time and place were — but also immaculately, and with small but noticeable excesses that ensured his desire for attention would never go unsated.

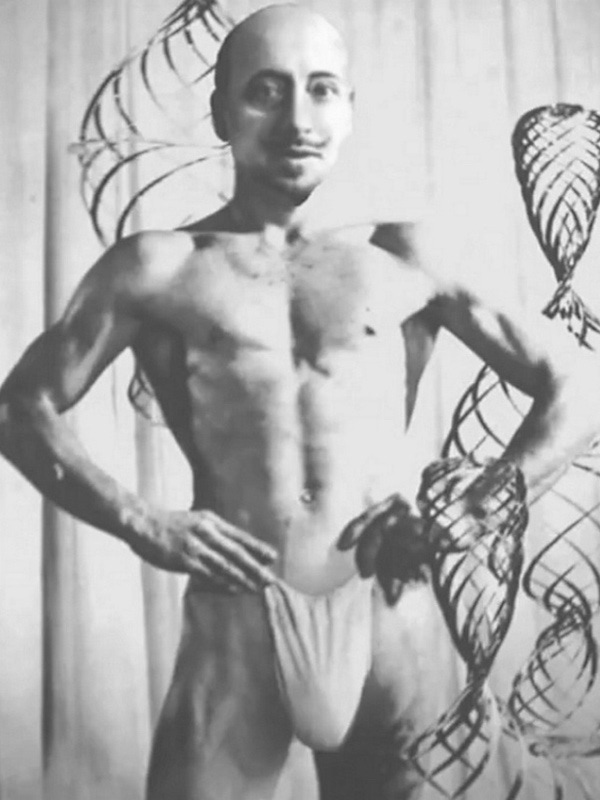

“beauty at any price, beauty appealing alike to the sense and the mind”A fin de siècle dandy at heart — his clothes always meticulously clean at a time when what we now know as hygiene remained a relatively novel idea — his club collars, of which he was particularly fond, were just that little bit larger than normal, his bow-tie just that extra touch more flamboyant, the favoured peaked lapels of his jacket always slightly wider than typical. His use of the latest pomades and colognes — he loved the scent of oranges — was widely noted, and he refused to wear any item of clothing that was not imported. Decades before Italy became a much sought-after global fashion and textiles powerhouse, native cloths were shunned in favour of those from France or Great Britain. His manservant described the master for whom he would lay out his daily dress each morning as “so obsessed with his appearance that his attitudes and gestures were so affected as to be perilously near effeminacy”. One slightly unnerving image of the poet has him posed like a cut-price Charles Atlas in just moustache and pouch in an attempt to define the Nietzschean Übermensch he thought he represented. Another, in military uniform, has him wearing a ceremonial dagger in his belt so that it points — pointedly — towards his well-employed genitals. Whether this was deliberate or not isn’t recorded.

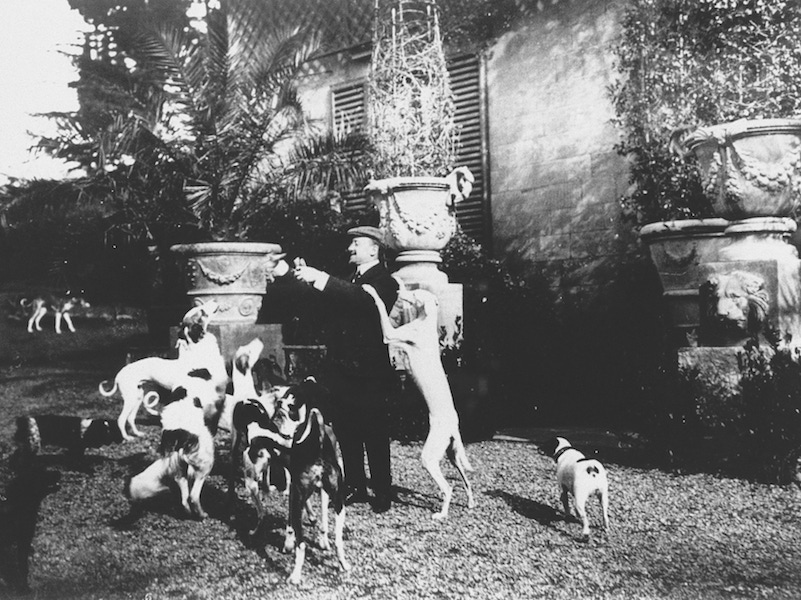

D’Annunzio’s flair for a life lived in the grand posture did not stop at his clothing: it included his surroundings too. He could shop until he didn’t drop: endless trips to the tailor, thousands of books, and he even once acquired 22 dogs and eight horses all in one purchase. When he stayed in hotels, he always travelled with his own sheets. “I am,” as he once explained with characteristic self-assuredness, “a better decorator and upholsterer than I am a poet or novelist.” Indeed, at the turn of this century, when his marriage into aristocracy along with his journalism and plays afforded him considerable wealth, he habitually lived in rented furnished houses that, at great expense, he immediately refurbished in extravagant fashion. Or, as he put it, in a style “gorgeous enough to be worthy of a Renaissance lord” — which involved filling his properties with mock 16th-century furniture of his own design.

Curiously, he also kept the interior of a home he rented in Settignano at near-tropical temperatures — perhaps explaining his enthusiasm for wearing little more than a kimono-style gown around the house. This also ensured he required little more than a slip off the shoulder in order to be, as his self-conception as a heroic male archetype no doubt necessitated, ready for action when it came to indulging in his many affairs, most famously with the actress Eleonora Duse.

Like D’Annunzio’s yen for all things luxurious, his penchant for role-playing never really left him. Towards the end of his life, he took to wearing a simple Franciscan monk’s habit — an outward suggestion of penitence perhaps, or a signifier of his putting aside temporal, earthly things in favour of the ascetic and would-be transcendent? Probably not, given that, underneath said habit, D’Annunzio always made sure to wear a pricey mauve silk shirt.

“Am I not the precursor of all that is good about Fascism?”Despite all the quixotic whimsy, his deeply ingrained love of romantic recklessness did find real manifestation, even a kind of greatness. He worked with Debussy on a musical setting for one of his poems, but casually turned down Puccini’s request that he write the libretto for an opera. Having seen the pioneering pilots of the early age of flight as modern knights, he became an avid aviator, taking part in air shows in front of crowds and the king. During World War I — which he ardently campaigned for Italy to be part of — he said that his many successful missions of dropping propaganda leaflets over enemy lines prompted in him feelings close to ecstasy. On hearing that the post-WWI Treaty of Versailles would cede the Dalmatian port of Fiume to the new Yugoslavia, he cobbled together a 2,000-strong private army of loyal followers — many women were star-struck by his magnetic personality, despite his unassuming looks — and marched on, seized and annexed the city, and proclaimed it an independent state. He declared himself to be its duce and ran the show with the help of an elite corps of SS-like soldiers that he dubbed, with the usual theatricality, “The Centurions of Death”. This situation held for two years until the nitty-gritty of achieving ends through political expediency — never D’Annunzio’s strong suit — became too much and he left for Venice, not so much even pursued as prosecuted. But even this adventure became an opportunity to make a statement through sartorialism. All of his followers dressed to his design: a black and silver uniform, topped with a black fez. His on-off friend, and perhaps protégé, one Benito Mussolini, looked on — soon after, he and his Blackshirts seized power in Rome and took on not just D’Annunzio’s dark style (sans fez), but also the straight-armed salute and the glorification of both virility and country. “Am I not the precursor of all that is good about Fascism?” D’Annunzio wrote to Il Duce in 1932. A hint, perhaps, that it could, or should, have been him at the capital. It’s an intriguing proposition, given that D’Annunzio couldn’t stand Hitler and that WWII began seven years later. Either way, what’s certain is that a fetishistic love of a certain uniform, bedecked with medals of dubious merit, infected the nation D’Annunzio helped to define, as much in substance as in style.